Le bonheur de vivre

| Le bonheur de vivre | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Henri Matisse |

| Year | Between October 1905 and March 1906 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 176.5 cm × 240.7 cm (69.5 in × 94.75 in) |

| Location | Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia |

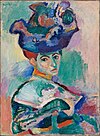

Le bonheur de vivre (The Joy of Life) is a painting by Henri Matisse. Along with Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Le bonheur de vivre is regarded as one of the pillars of early modernism.[1] The monumental canvas was first exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants of 1906, where its cadmium colors and spatial distortions caused a public expression of protest and outrage.[1]

Description

[edit]In the painting, nude women and men cavort, play music, and dance in a landscape drenched with vivid color. In the central background of the piece is a group of figures that is similar to the group depicted in his painting The Dance (1909–10).

Inspiration

[edit]Art historians James Cuno and Thomas Puttfarken have suggested that the inspiration for the work was Agostino Carracci's engraving of Reciproco Amore or Love in the Golden Age after the similarly named painting by the 16th-century Flemish painter Paolo Fiammingo. Based on the many similarities with the engraving, in particular its theme of pastoral fantasy and its composition with the circle of dancers in the background, Cuno came to the conclusion that Carracci's engraving had a decisive influence on the final composition of Le Bonheur de Vivre.[2][3][4]

Since the 1980s, art historians have debated the importance of tracing exact sources of inspiration, arguing that this distracts from Matisse's intervention.[5][6][7] Though Matisse invokes the tradition of the pastoral landscape, his colors, forms, and figures refuse clear or simple meanings or associations.[5][7]

This painting seems to be Matisse's considered response to the hostility his Fauvist work had met with in the Salon d'Automne in 1905.[8][9] He made many preparatory sketches of the figures and a cartoon of the composition.[9]

Cultural impact

[edit]When it was exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in 1906, it was widely criticized for its ambiguous theme and lack of stylistic consistency.[10] Some critics even worried that this was the end of French painting.[10]

French Pointillist painter Paul Signac, who had purchased some of Matisse's earlier works, wrote:

Matisse, whose attempts I have liked up to now, seems to me to have gone to the dogs. Upon a canvas of two-and-a-half meters, he has surrounded some strange characters with a line as thick as your thumb. Then he has covered the whole thing with flat, well-defined tints, which—however pure—seem disgusting.[11]

However, other artists found it inspirational. "Pablo Picasso, who, in an effort to outdo Matisse in terms of shock value, immediately began work on his watershed Les Demoiselles D’Avignon," writes Martha Lucy, associate curator at the Barnes Foundation.[1] This "irritated" Matisse.[12]

But by the 1920s, the painting was accepted as a modern masterpiece. Matisse himself considered it one of his most important artworks.[11]

Art critic Hilton Kramer wrote that Le bonheur de vivre was "the least familiar of modern masterpieces," because it was long held by the Barnes Foundation, which did not allow color reproductions for many years, while the museum itself was until 2012 located in suburban Merion, Pennsylvania.[8]

Conservation

[edit]Le bonheur de vivre features a large amount of cadmium sulfide-based yellow. Portions of the painting containing cadmium sulfide are turning white or brown, degrading the work. University of Delaware Professor Robert L. Opila, in collaboration with Barbara Buckley, head of conservation at the Barnes, and Jennifer Mass, a senior scientist and head of the Scientific Research and Analysis Laboratory at Winterthur, studied the paint's material microstructure in an attempt to determine why the cadmium sulfide is changing color.[1][13]

“It is a very disheartening phenomenon, considering the painting’s position in history,” says Opila, professor of materials science at UD.[1][13]

Preliminary tests carried out by UD doctoral student Jonathan Church at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France, show that carbon dioxide is reacting with the cadmium sulfide, causing the formation of cadmium carbonate, which is white. Also, the presence of chloride in the paint appears to be acting as a catalyst for the deterioration. Opila and his research team theorize that the binder, an oil similar to linseed oil, may be turning brown.[1][13]

“The scientific studies being undertaken will contribute significantly to the preservation of the painting and to our understanding of the change that has taken place to the visual appearance of the painting,” says Buckley.[1][13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "Martha Lucy, Matisse Mystery, the Barnes Foundation". Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ^ James B. Cuno, Matisse and Agostino Carracci: A Source for the Bonheur de Vivre, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 122, No. 928, Special Issue Devoted to Twentieth Century Art (Jul., 1980), pp. 503–505

- ^ Thomas Puttfarken, Mutual Love and Golden Age: Matisse and ‘gli Amori de’ Carracci, Burlington Magazine 124 (Apr. 1982): 203–208.

- ^ "Andrew Graham-Dixon, The Dance by Henri Matisse". Archived from the original on August 9, 2014.

- ^ a b Werth, Margaret. “Engendering Imaginary Modernism: Henri Matisse’s Bonheur de Vivre.” Genders, no. 9 (November 1, 1990): 49–74.

- ^ Bois, Yves-Alain. “On Matisse: The Blinding.” Translated by Greg Sims. October 68 (Spring 1994): 61–121.

- ^ a b Wright, Alastair. Matisse and the Subject of Modernism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

- ^ a b Kramer, Hilton, The Triumph of Modernism: The Art World, 1985–2005, 2006, Reflections on Matisse, p. 162. ISBN 0-15-666370-8

- ^ a b Bois, Yves-Alain. “1906: Postimpressionism's Legacy to Fauvism.” In Art Since 1900, edited by Yves-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Hal Foster, and Rosalind Krauss, 3rd ed., 1:88-89. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2016.

- ^ a b Wright, Alastair. Matisse and the Subject of Modernism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004. 93-99.

- ^ a b Bois, Yves-Alain. “Matisse and ‘Arche-Drawing’.” In Painting as Model, 3–64. An October Book. MIT Press, 1993, p. 18. Footnote 41: "Letter of January 14, 1906, quoted in Alfred Barr, Matisse, His Art and His Public (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1951), p. 82.

- ^ Bois, Yves-Alain. “On Matisse: The Blinding.” Translated by Greg Sims. October 68 (Spring 1994): 102. Footnote 125 reads: See Helene Seckel's detailed account of the matter in the catalog of the exhibition devoted to Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, which she organized at the Musee Picasso in Paris in 1988 (vol. 2, pp. 671–72).

- ^ a b c d "Materials science reveals clues about pigment degrading on painting". www1.udel.edu.

External links

[edit]- Barnes Foundation, Le Bonheur de vivre

- Photo-oxidative degradation of yellow pigments in Matisse’s Le Bonheur de Vivre (1905-6): a comparison of XANES, XPS, Raman, and FTIR methodologies. [O-1] Jennifer Mass (Winterthur Museum, Scientific Research and Analysis Laboratory, Winterthur, Delaware, U.S.A.)

- Cadmium yellow degradation mechanisms in Henri Matisse’s Le Bonheur de vivre (1905-6) compared to the Munch Museum’s The Scream (1910) using chemical speciation as a function of depth, Jennifer L. Mass, et al