2019–2020 COVID-19 outbreak in mainland China

| COVID-19 pandemic in mainland China | |

|---|---|

Confirmed COVID-19 cases in mainland China per 100,000 inhabitants by province as of 3 October 2020[update][1]

118.25 cases per 100,000 (Hubei)

3–5 cases per 100,000

1–3 cases per 100,000

0.5–1 cases per 100,000

>0–0.5 cases per 100,000

| |

| Disease | COVID-19 |

| Virus strain | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Location | Mainland China |

| First outbreak | Wuhan, Hubei[2] |

| Index case | 1 December 2019 (4 years, 8 months, 2 weeks and 4 days ago) |

| History of the People's Republic of China |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

The 2019–2020 COVID-19 outbreak in mainland China was the first COVID-19 outbreak in that country, and the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). China was the first country to experience an outbreak of the disease, the first to impose drastic measures in response (including lockdowns and face mask mandates), and one of the first countries to bring the outbreak under control.

The outbreak was first manifested as a cluster of mysterious pneumonia cases, mostly related to the Huanan Seafood Market, in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province. On 8 January 2020, a new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) was identified as the cause of the pneumonia by Chinese scientists.[3] During the beginning of the pandemic, the Chinese government showed a pattern of secrecy and top-down control.[4] It censored discussions about the outbreak since the beginning of its spread, from as early as 1 January,[5][6] worked to censor and counter reporting and criticism about the crisis – which included the detention of several citizen journalists[7] – and portray the official response to the outbreak in a positive light,[8][9][10] and restricted and facilitated investigations probing the origins of COVID-19.[4][11] Several commentators suspected the Chinese government had deliberately under-reported the extent of infections and deaths.[12][13][14] However, some academic studies have found no evidence that China manipulates COVID-19 data.[15][16][17]

The local governments of Wuhan and Hubei were widely criticized for their delayed responses to the virus and their censorship of the related information during the initial outbreak, especially during the local parliamentary sessions. This allowed early spread of the virus,[18] as a large number of Chinese people returned home for the Chinese New Year vacation from and through Wuhan, a major transportation hub.[19][20] However, stringent measures such as lockdown of Wuhan and the wider Hubei province and face mask mandates were introduced around 23 January,[21] which significantly lowered and delayed the epidemic peak according to epidemiology modelling.[22] Yet, by 29 January, the virus was found to have spread to all provinces of mainland China.[23][24][25] By the same date, all provinces had launched high-level public health emergency responses.[26] Many inter-province bus services[27] and railway services were suspended.[28] On 31 January, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.[25] A severe shortage of face masks and other protective gear[29] led several countries to send international aid, including medical supplies, to China.[30][31][32]

By late February, the pandemic had been brought under control in most Chinese provinces. On 25 February, the reported number of newly confirmed cases outside mainland China exceeded those reported from within for the first time; the WHO estimated that the measures taken in the country averted a significant number of cases.[33] By 6 March the reported number of new cases had dropped to fewer than 100 nationally per day, down from thousands per day at the height of the crisis. On 13 March, the reported number of newly imported cases passed that of domestically transmitted new cases for the first time.[34]

By the Summer of 2020, widespread community transmission in China had been ended, and restrictions were significantly eased.[35] Sporadic local outbreaks caused by imported cases have happened since then, which authorities responded to with testing and restrictions.[36] Different neighbourhoods or townships were classified into high-, medium- or low-risk based on the number of confirmed cases and whether there were cluster cases,[37] which formed the basis for the gradual easing of lockdown measures since March.[38] Lockdown in hard-hit Wuhan was officially lifted on 8 April.[39]

China is one of just a few of countries that have pursued a zero-COVID strategy, which aims to eliminate transmission of the virus within the country and allow resumption of normal economic and social activity.[40]

Despite concerns about automated social control, health codes generated by software have been used for contact tracing: only people with green code can move freely, while those with red or yellow code need to be reported to the government.[39][41] With domestic tourism first reopened among the pandemic-hit industries,[42][43] China's economy continued to broaden recovery from the recession during the pandemic, with stable job creation and record international trade growth, although retail consumption was still slower than predicted.[44][45] China was the only major economy to report economic growth in 2020.[46]

In July 2020, the government granted an emergency use authorization for two COVID-19 vaccines.[47][48] It has also pledged or provided humanitarian assistance to other countries dealing with the virus.[8][9]

Graphics

[edit]Initial outbreak

[edit]Discovery

[edit]

Based on retrospective analysis published in The Lancet in late January, the first confirmed patient started experiencing symptoms on 1 December 2019,[49] though the South China Morning Post later reported that a retrospective analysis showed the first case may have been a 55-year-old patient from Hubei province as early as 17 November.[50][51] On 27 March 2020, news outlets citing a government document reported a 57-year-old woman, who started having symptoms on 10 December 2019 and subsequently tested positive for the COVID-19 disease may have been the index case in the COVID-19 pandemic.[52][53] Although the first confirmed patient did not have any exposure to Huanan Seafood Market, an outbreak of the virus began among the people who had been exposed to the market nine days later.[19][54]

The outbreak went unnoticed until 26 December 2019, when Zhang Jixian, director of the Department of Respiratory Medicine at Hubei Xinhua Hospital, noticed a cluster of patients with pneumonia of unknown origin, several of whom had connections to the Huanan Seafood Market.[55] She subsequently alerted the hospital, as well as municipal and provincial health authorities, which issued an alert on 30 December.[55][56] Results from patient samples obtained on 29–30 December indicated the presence of a novel coronavirus, related to SARS.[55] On 1 January 2020, Jianghan District's Health Agency and Administration for Market Regulation closed down the seafood market and collected samples for testing.[57]

On 28 December 2019, Lili Ren, a virologist at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College in Beijing uploaded a partial sequence of the COVID-19 virus's structure to the United States National Institutes of Health's GenBank. The NIH did not publish the submission, as it did not include technical information required by the institute's rules, and attempts by the NIH to contact Ren went unanswered. On 17 January 2024, The Wall Street Journal released a report about the 28 December upload.[58]

The World Health Organization (WHO) issued its first report on the outbreak on 5 January 2020.[59] Professor Zhang Yongzhen of Fudan University completed sequencing of the novel virus almost identical to the previous 28 December upload on 5 January.[58] On 8 January 2020, a new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) was announced by Chinese scientists as the cause of the new disease.[60] Professor Yongzhen published the results to the online database GenBank on 11 January.[55]

On 14 January, the WHO tweeted:

Preliminary investigations conducted by the Chinese authorities have found no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) identified in Wuhan, China.

— [61]

On 15 February 2021, WHO investigators in China said they had found evidence that the initial outbreak in Wuhan was more widespread than originally thought. They asked the Chinese government for permission to study hundreds of thousands of blood samples from Wuhan; as of 15 February, this permission had not been granted.[62]

Measures and impact in Hubei

[edit]

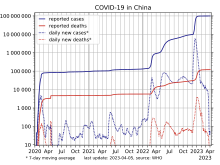

Semi-log graph of 3-day rolling average of new cases and deaths in China during COVID-19 epidemic showing the lockdown on 23 January and partial lifting on 19 March.

Within three weeks of the first known cases, the government built sixteen large mobile hospitals in Wuhan and sent 40,000 medical staff to the city.[63]: 137

A retrospective study of antibody prevalence estimated that close to 500,000 people in Wuhan may have been infected during the outbreak.[64]

Spreading beyond Hubei

[edit]

On 25 January, Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping warned that China was facing a 'grave situation'.[65][66] He held a Party Politburo meeting which promised resources and experts for treatment and supplies to Hubei[67] as more and more cases of the viral infection, mostly exported from Wuhan were confirmed in other cities in Hubei[23] and multiple parts in mainland China.[68] On 29 January, Tibet announced its first confirmed case, a male who traveled from Wuhan to Lhasa by rail on 22–24 January[69] which marked that the virus spread to all parts of mainland China.[23][24][25]

The 25 January Chinese New Year celebrations were canceled in many cities. Public transportation passengers were checked for their temperatures to see whether they had a fever.[70] Henan, Wuxi, Hefei, Shanghai, Inner Mongolia suspended trade of living poultry on 21 January.[71]

Public Health Emergency declarations

[edit]By 21 January, government officials warned against hiding the disease.[72]

On 22 January, Hubei launched a Class 2 Response to Public Health Emergency.[73] Ahead of the Hubei authorities, a Class 1 Response to Public Health Emergency, the highest response level was announced by the mainland province of Zhejiang on 23.[74][75] Guangdong and Hunan followed suit later on the day. On the following day, Hubei[68] and other 13 mainland provinces[76][77][78][79] also launched a Class 1 Response. By 29, all parts of mainland initiated a Class 1 Response after Tibet upgraded its response level on that day.[26]

The highest response level authorizes a provincial government to requisition resources under the administration to control the epidemic. The government was allowed to organize and coordinate treatment for the patients, make investigations into the epidemic area, declare certain areas in the province as an epidemic control area, issue compulsory orders, manage human movement, publish information and reports, sustain social stability and to do other work related to epidemic control.[80]

Social impacts

[edit]Holidays, tourism and events

[edit]On 26 January, the State Council extended the 2020 Spring Festival holiday to 2 February (Sunday, the ninth day of the first lunar month) with 3 February (Monday) marking the start of normal work. The educational institutions postponed the start of school.[81] The different provinces made their own policies about holiday extension.[82]

Miss Universe China 2020 was originally scheduled to take place on 8 March 2020; however, on 21 February 2020, the Miss Universe China Organization announced that the pageant was cancelled and postponed to a later date due to the pandemic.[83] The new date was later announced as 9 December 2020.

On 21 January, the Wuhan Culture and Tourism Bureau postponed a tourism promotion activity to the city's citizens. All qualified citizens will be able to continue the qualification in the Bureau's next activity.[84] On 23 January, the Bureau announced the temporary closing of museums, memorials, public libraries and cultural centers in Wuhan from 23 January to 8 February.[85] All tour groups to and from Wuhan will be canceled.[86][87]

On 23 January, the City Administration of Dongcheng, Beijing cancelled temple fairs in Longtan and Temple of Earth, originally scheduled for 25 January.[88] The Beijing Culture and Tourism Bureau later announced cancellations of all major events including temple fairs.[89] The tourist attractions in Beijing[90] and Tianjin,[91] including the Forbidden City and the National Maritime Museum closed their doors to the public from 24 January. On the evening of 23 January, the Palace Museum decided to shut down from 25 January[92] and the West Lake in Hangzhou announced shutting all paid attractions and the Music Fountain down and suspended the services of all large-scale cruise ships starting the next day.[93] Since 24 January, many major attractions are shut down nationwide including the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum in Nanjing,[94] Shanghai Disneyland, Pingyao Ancient City in Shanxi, Canton Tower in Guangdong, the Old Town of Lijiang, Yunnan and Mount Emei in Sichuan.[95]

Sports

[edit]For the 2020 Olympic women's football qualifier, the third round of the Group B matches for the Asian division was planned to be held in Wuhan and later Nanjing,[96] but the match was finally held in Sydney, Australia.[97] The 2020 Chinese FA Super Cup, to be held in Suzhou on 5 February 2020 was postponed.[98] The 2020 Asian Champions League play-off match between Shanghai SIPG and Buriram United were played behind closed doors.[99] The Chinese Football Association announced that the 2020 season is postponed from 30 January.[100] The Asian Football Confederation postponed all home matches for Chinese clubs in the Champions League group stage. The three of them had not played a single game yet as of 3 March 2020.[101]

The Olympic boxing qualifier[102][103] has also been rescheduled to March and the venue has been moved to Amman, Jordan.[104] The Group B of the Olympic women's basketball qualifiers, originally scheduled to be held in Foshan, Guangdong was also moved to Belgrade, Serbia.[105]

As for the other major sports events, FIS Alpine Ski World Cup, scheduled for 15–16 February 2020 was canceled due to the outbreak. The event was originally planned to be the 2022 Winter Olympics' first test. The 2020 World Athletics Indoor Championships, originally scheduled to take place in Nanjing from 13 to 15 March are postponed for a year and will be held at the same venue.[106] The Confederations Cup Asia Pacific Group I, scheduled to be held in Dongguan, Guangdong was moved to Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan.[107]

The State General Administration of Sports announced a suspension of all sporting events until April. The Mudanjiang Sports Culture Winter Camp[108] and China Rally Championship Changbai Mountains[109] are both suspended. After the postponement of national women's basketball games, the Chinese Volleyball Association suspended all volleyball matches and activities.[110]

The 2020 Sanya ePrix, due to take place on 21 March as the third round of the Formula E season was postponed to a yet to be announced date.[111] On 12 February, the 2020 Chinese Grand Prix, due to take place on 19 April as the fourth round of the 2020 Formula One World Championship was also postponed.[112]

The Lingshui China Masters badminton tournament, scheduled to commence on 25 February to 1 March 2020 was postponed to early May.[113]

China's 14th National Winter Games, originally scheduled for 16–26 February were also postponed.[114]

Education

[edit]On 21 January 2020, the Ministry of Education (MoE) requested the education system to do a good job in the prevention and control of pneumonia caused by novel coronavirus infection. After that, private education providers including New Oriental, NewChannel and TAL Education,[115] education departments in Hubei,[116] Zhejiang,[117] Shenzhen,[118] and Shanghai University[119] cancelled all ongoing courses and postponed the new semester. On 27 January, MoE advised all higher education institutions to postpone the new spring semester with all local education departments to determine the starting time of the new semester for K-12 education and local colleges according to the decision of the local governments.[120] The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security also decided to put the new semester off for all vocational education facilities.[121]

The National Education Examinations Authority canceled all IELTS, TOEFL and GRE exams scheduled for February. The decision was first made for tests to be held in Wuhan and extended to those in all parts of mainland China.[122][123] MoE also urged the Chinese students studying abroad to delay their travels. For those who need to go abroad, MoE advised them to arrive earlier in case of any kind of health check and to stop traveling if they have any signs of coughing and fever.[124]

On 28 January, the National Civil Service Bureau said that it would postpone the 2020 civil service recruitment examination, public selection and public selection interview time.[125]

Civil life

[edit]Civil Affairs authorities in Shanghai, Hangzhou, Guangzhou, Jinan, Ningbo and Gansu announced on 25 January that they would cancel the special arrangement of marriage registration scheduled for 2 February 2020 to avoid the spread of the epidemic and cross-infection caused by the gathering of people.[126][127][128][129] Later, on 30 January, the Ministry of Civil Affairs ordered to cancel marriage registrations on 2 February.[130]

Religion

[edit]The government of China, which upholds a policy of state atheism, used the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic to continue its antireligious campaigns, demolishing Xiangbaishu Church in Yixing and removing a Christian Cross from the steeple of a church in Guiyang County.[131][132]

Politics

[edit]

The outbreak made an impact on the National People's Congress (NPC), China's national parliament and many local parliaments. On 27 January, the Provincial People's Congress Standing Committee (PPCSC) of Yunnan announced to postpone local Lianghui sessions scheduled for early February which was followed by the PPCSC of Sichuan on 28 January. The local parliament sessions of cities including Hohhot, Chengdu, Jinan, Qingdao, Binzhou, Zhengzhou, Pingdingshan, Anyang, Hefei, Changzhou, Ningbo, Wenzhou, Zhoushan, Ganzhou, Shangluo, and Jiangjin were also put off.[133]

The NPC's Standing Committee will discuss on 24 February to decide whether to delay its March session or not.[134] The 10-day session in March is an annual gathering of about 3,000 delegates from all parts of China where the major laws are passed and key economic targets are unveiled. The potential delay will be the first time since 1995 when the NPC first adopted the schedule for the March session.[135] Willy Lam, a political analyst at the Chinese University of Hong Kong believed that the sessions may not only increase the risk of infections but also "post hostile and embarrassing questions to the top officials about the outbreak." He also believed that canceling the meetings would be possible although this never happened after the Cultural Revolution.[136]

Economic impact

[edit]In late January, economists predicted a V-shaped recovery. By March, it was much more uncertain.[137] Millions of workers were stranded far from their jobs while the workplaces were short-handed. The data for February 2020—the first full month after the virus became a major factor in January—saw official indicators of economic activity fall to record lows. The Caixin manufacturing index (PMI) fell to 35.7 in February from 50 in January, showing a deep contraction. The nation's non-manufacturing index sank even further to a record low of 29.6 in February from 54.1 in January 2020. According to The Wall Street Journal, "The factory index indicated contraction for most of 2019, hit by a trade war between the United States and China. It didn't cross back into expansion until late [2019] when trade tensions between the two sides eased."[138]

China's economic growth is expected to slow by up to 1.1 percentage in the first half of 2020 as economic activity is negatively affected by the new COVID-19 outbreak, according to a Morgan Stanley study cited by Reuters.[139] But, on 1 February 2020, the People's Bank of China said that the impact of the epidemic on China's economy was temporary and the fundamentals of China's long-term positive and high-quality growth remained unchanged.[140]

Due to the outbreak, the Shanghai Stock Exchange and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange announced that with the approval of the China Securities Regulatory Commission, the Spring Festival holiday was extended to 2 February and trading will resume on 3 February.[141][142] Before that, on 23 January, the last trading day of shares before the Spring Festival, all three major stock indexes opened lower, creating a drop of about 3% and the Shanghai index fell below 3000.[143] On 2 February, the first trading day after the holiday, the three major indexes even set a record low opening of about 8%.[144] By the end of the day, the decline narrowed to about 7%, the Shenzhen index fell below 10,000 points, and a total of 3,177 stocks in the two markets fell.[145]

The People's Bank of China and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange announced that the inter-bank RMB foreign exchange market, the foreign-currency-to-market and the foreign-currency market will extend their holiday closed until 2 February 2020.[146] When the market opened on 3 February, the Renminbi declined against major foreign currencies. The central parity rate of the Renminbi against the US dollar opened at 6.9249, a drop of 373 basis points from the previous trading day.[147] It fell below the 7.00 than an hour after the opening,[148] and closed at 7.0257.[149]

The sale of new cars in China was affected by the outbreak. There was a 92% reduction on the volume of cars sold during the first two weeks of February 2020.[150] According to the sources of Automative News, Chinese policymakers had discussed the extension of subsidies for electric-vehicle purchases beyond this year to revive sales,[150] while also discussing reducing requirements for zero-emission vehicle shares of production.[151]

By 13 March, most business outside of Hubei was active again.[152] The Caixin PMI increased to 50 at the end of March.[153]

During Q1 2020, China's GDP dropped by 6.8 percent, the first contraction since 1992.[154]

In May 2020, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang announced that, for the first time in history, the central government wouldn't set an economic growth target for 2020, with the economy having contracted by 6.8% compared to 2019 and China facing an "unpredictable" time. However, the government also stated an intention to create 9 million new urban jobs until the end of 2020.[155]

By late 2020, the economic recovery was accelerating amid increasing demand for Chinese manufactured goods.[156] The UK-based Centre for Economics and Business Research projected that China's "skilful management of the pandemic" would allow the Chinese economy to surpass the United States and become the world's largest economy by nominal GDP in 2028, five years sooner than previously expected.[157][158] However, a government report cautioned that the recovery was "not yet solid".[159]

Unemployment

[edit]In January and February 2020, during the height of the epidemic in Wuhan, about 5 million people in China lost their jobs.[160] Many of China's nearly 300 million rural migrant workers have been stranded at home in inland provinces or trapped in Hubei province.[161][162]

By the end of March, as many as 80 million workers may have been unemployed, according to an estimate by economist Zhang Bin of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences; this estimate included migrant workers and people in rural areas, whom the official statistics from Beijing do not take into account.[163]

Face mask shortage and production

[edit]

In China, face masks have been used widely by the general public during the pandemic, and have been required in many locations.[164] As the epidemic accelerated, the mainland market saw a shortage of face masks due to the increased need from the public.[165] It was reported that Shanghai customers had to queue for nearly an hour to buy a pack of face masks which was sold out in another half an hour.[166] Some stores are hoarding, driving the prices up and other acts so the market regulator said that it will crack down on such acts.[167][168] The shortage will not be relieved until late February when most workers return from the New Year vacation according to Lei Limin, an expert in the industry.[169][needs update]

On 22 January 2020, Taobao, China's largest e-commerce platform owned by Alibaba Group said that all face masks on Taobao and Tmall would not be allowed to increase in price. The special subsidies would be provided to the retailers. Also, Alibaba Health's "urgent drug delivery" service would not be closed during the Spring Festival.[170] JD, another leading Chinese e-commerce platform said, "We are actively working to ensure supply and price stability from sources, storage and distribution, platform control and so on" and "while fully ensuring price stability for JD's own commodities, JD.com also exercised strict control over the commodities on JD's platform. Third-party vendors selling face masks are prohibited from raising prices. Once it is confirmed that the prices of third-party vendors have increased abnormally, JD will immediately remove the offending commodities from shelves and deal with the offending vendors accordingly."[171] The other major e-commerce platforms including Sunning.com and Pinduoduo also promised to keep the prices of health products stable.[172][173]

Figures from China Customs show that some 2.46 billion pieces of epidemic prevention and control materials had been imported between 24 January and 29 February, including 2.02 billion masks and 25.38 million items of protective clothing valued at 8.2 billion yuan ($1 billion). Press reported that the China Poly Group, together with other Chinese companies and state-owned enterprises, had an important role in scouring markets abroad to procure essential medical supplies and equipment for China.[174] Risland (formerly Country Garden) sourced 82 tonnes of supplies, which were subsequently airlifted to Wuhan.[175]

By March, China has been producing 100 million masks per day to meet the demand of medical staff and general public.[176]

Environment

[edit]The slowdown in manufacturing, construction, transportation and overall economic activity created a temporary reduction by about a quarter in China's greenhouse gas emissions.[177]

Lockdown and curfew

[edit]

Ever since Hubei's lockdown, areas bordering Hubei including Yueyang in Hunan and Xinyang in Henan set up checkpoints on roads connecting to Hubei to monitor cars and people coming from Hubei.[178][179] Between 24 and 25 January, the local governments of Shanghai, Jiangsu, Hainan and other areas announced to quarantine passengers from "key areas" of Hubei for 14 days.[180][181] Chongqing also announced mandatory screening of every person who arrived from Wuhan since 1 January, and set up 3 treatment centers.[182]

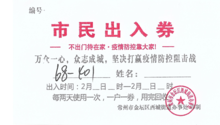

Since 1 February 2020, a curfew law that resembles that of Huanggang, Hubei, was put in place by the city of Wenzhou in Zhejiang, which is the second largest center after Hubei. Each local family can appoint one family member who may leave their house to purchase essential goods every two days.[183] Since 4 February Zhejiang's capital, Hangzhou, announced the closure of all of its villages, residential communities and work units to guests. Those who enter and exit these places must show valid identification papers. Non-residents and cars will be checked strictly.[needs update][184][185] On the same day, Yueqing, Ningbo, Zhengzhou, Linyi, Harbin, Nanjing, Xuzhou and Fuzhou began to take the same approach.[186] Zhumadian, Henan, announced that each family were only allowed to have one member leave the house to purchase essential goods every 5 days.[187]

Factories were closed or reduced production for a few weeks. When they opened again, measures were implemented to reduce risk.[188][189]

Many local governments implemented restrictions to control the outbreak, including keeping schools closed, cutting off villages, and restricting travel.[190][191] A smartphone-based health-tracking system was introduced in much of the country.[192]

The media were issued directives instructing them not to use certain terms:

... 各媒体在报道限制出行、受控出入等防控举措时,不使用封城、封路、封门、封条等提法。[193]

... when reporting on limits on travel, controls on movement[,] and other prevention and control measures, do not use formulations like lockdown, road closures, sealed doors[,] or paper seals.

— Cyberspace Administration of China, internal government directive given to all news media, February 2020[193]

On 25 March, all lockdowns in Hubei outside of Wuhan were lifted. On 8 April, all lockdowns were lifted in Wuhan.[194] The strict lockdown of Wuhan during the outbreak set the precedent for similar measures in other Chinese cities during the following outbreaks.

Further outbreaks in 2020

[edit]On 2 April 2020, the government ordered a Hubei-like lockdown in Jia County, Henan, after a woman tested positive for the COVID-19. It is suspected that she may have been infected when she visited a hospital where three doctors tested positive for the virus, despite showing no symptoms.[195]

On 9 April, a COVID-19 cluster was detected in Heilongjiang Province, which started with an asymptomatic patient returning from the United States and quarantining at home. The US CDC reported that the infections were initially spread through a shared elevator used at different times, and led to at least 71 cases by 22 April.[196]

In early May, restrictions were tightened in Harbin.[197]

In June, an outbreak with 45 people testing positive at Xinfadi Market in Beijing caused some alarm.[198] Authorities closed the market and nearby schools; eleven neighborhoods in the Fengtai District started requiring temperature checks and were closed to visitors.[199] By this time, public health technology included special leaf blower backpacks designed to vent hot air onto outdoor surfaces.[200] By the evening of 23 June, Chinese Vice Premier Sun Chunlan declared that the situation had been brought under control.[201] China's traffic authorities vowed to strictly guard traffic out of Beijing: those with abnormal health QR codes or without recently-taken negative PCR test proof would not be allowed to take public transportation or drive out of the capital.[202][203][204]

On 26 July, China saw its highest number of daily cases since March, mostly from outbreaks in Xinjiang and Liaoning.[205] with 61 new cases, up from 46 cases a day earlier,[206] This increased to 127 daily COVID cases on 30 July.[207] The daily reported cases subsequently went down, to 16 on 23 August.[208]

In July, Xinjiang province and its capital Ürümqi were locked down in the wake of the discovery of new cases in the city.[209][210]

On 11 October, officials in Qingdao urged to carry out contact tracing and mass testing after 12 new cases were found connected to the Qingdao Chest Hospital. On 12 October, it was announced that Qingdao would test all 9 million of its residents.[211]

In October, 137 asymptomatic cases were detected in Kashgar, Xinjiang and were linked to a garment factory.[212][213]

On 18 December, a local case was reported in Beijing. It was the first local infection in 152 days in Beijing. As of 27 December, thirteen more cases have been detected.[214] Another outbreak linked to a traveler from South Korea was reported in Liaoning late December.[215]

International and regional relations

[edit]Information sharing

[edit]China's scientists have been praised for rapidly sharing information on the virus to the international community,[216][217] and leading some of the world's research on the disease.[218] Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang said on 21 January that the Chinese authorities would share information of the epidemic "with the WHO, relevant nations and China's Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan regions in a timely manner including the genome sequence of the new coronavirus."[219] During the sidelines of the World Economic Forum, Germany's health minister Jens Spahn praised China for its improved transparency since 2003.[220] US officials and WHO also praised China for sharing data about the epidemic and keeping transparent. The US experts had been invited by China's NHC.[221] On 23 January, the WHO director-general, Tedros Adhanom and the WHO regional director for the Western Pacific, Takeshi Kasai, arrived in Beijing to discuss the new coronavirus outbreak with the Chinese authorities and health experts.[222] China agreed on 28 January that the WHO would send international experts to China.[223]

John Mackenzie, a member of the World Health Organization's emergency committee criticized China for being too slow to share all of the infected cases, especially during major political meetings in Wuhan after Tedros Adhanom praised China for helping "prevent the spread of coronavirus to the other countries."[224] US President Donald Trump said that China was "very secretive and that's unfortunate" regarding the information on the pandemic.[225] Yanzhong Huang, a health expert at Seton Hall University, said that China could have been more forceful and "when there was a cover-up and there was inaction".[226]

A number of other countries' governments have called for an international examination of the virus's origin and spread.[227][228]

After an initial block, the Chinese government granted permission for a WHO team to visit China and investigate COVID-19's origins. In January 2021, Tedros Adhanom expressed his dismay as China blocked the team's entry.[229] The Chinese government had previously agreed to allow the team's entry.[230][231] A few days later, permission was granted for the team to arrive.[232][11][233] A WHO-affiliated health expert said expectations that the team would reach a conclusion from their trip should be "very low".[234]

Evacuations

[edit]Multiple countries evacuated or are trying to evacuate their citizens from Wuhan including South Korea, Japan, the US, the UK, Kazakhstan, Germany, Spain, Canada, Russia, the Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand, Indonesia, France, Switzerland and Thailand.[235] Korean media Channel A said that China asked the evacuation flights to arrive in the evening and leave Wuhan in the next morning so the evacuation would not be seen by the public.[236] According to BBC, any Chinese national, even with a UK citizenship is not allowed to be evacuated by the UK.[237]

Taiwan

[edit]After initially refusing to allow Taiwanese citizens to evacuate due to the One-China policy,[238] the Chinese government eventually allowed Taiwan to evacuate its nationals from Wuhan with the assistance of the local Taiwan Affairs Office.[239] There were around 500 Taiwanese trapped in Wuhan. The first flight to help them leave left Wuhan on 3 February.[240] All of them would be quarantined for two weeks after they enter Taiwan.[239]

The evacuation halted after the first flight was found to carry an infected case. The Taiwanese government said that the person was not in the evacuation list and the most vulnerable were not included in the first flight. It also said that it was not prepared to take these people with a high risk of viral infections home.[241] Tsai Ing-wen criticized China's attempt to rule Taiwan out in WHO and said, "The information obtained by the WHO was obviously inaccurate ... and could cause the WHO to make mistakes in dealing with the global epidemic."[242] Premier Su Tseng-chang called for a government-to-government negotiation for the following arrangement of chapter flights[243] despite the fact that the cross-strait communication mechanism between governments had been suspended since 2016 when Tsai was elected president.[244]

The State Council's Taiwan Affairs Office urged the Taiwanese government to stop impeding the evacuation.[245] The office said that before the flight, all of the passengers signed a personal declaration claiming that they have no contact with any confirmed or suspected cases and promising to comply with quarantine measures after returning to the island. All of the passengers are checked for their temperature three times before the flight and showed no abnormality. The office said critically that the Taiwanese government first expressed appreciation before the flight, but changed its attitude after the flight.[246] Wuhan's Taiwan Affairs Office asked Taiwan for more details about the infected case as the basic descriptions of the patient including age and gender were not given as previously 17 cases in Taiwan. The office also said that the patient's close relatives were not at all informed of the viral infection.[247]

Immigration control

[edit]

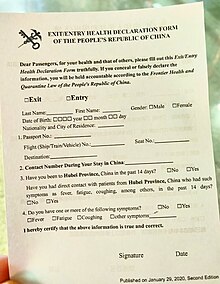

The State Administration of Immigration promised that the border inspection agencies at all ports of entry and exit in China would continue to provide necessary facilities and services for Chinese citizens returning home.[249] On 25 January, the General Administration of Customs reactivated the health declaration system where people entering or exiting mainland China are asked to write a health declaration. Border control staff shall also cooperate in health and quarantine work such as body temperature monitoring, medical inspection, and medical check-up.[250] On 31 January, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that it was arranging charter flights to take the Chinese citizens from Hubei and Wuhan back to Wuhan 124, given the practical difficulties that they faced overseas.[251]

Hubei suspended the processing of applications from mainland Chinese residents for entry and exit of mainland China. For those with a valid visa to enter Hong Kong and Macao, but fail to enter the areas due to the COVID-19 outbreak, the Chinese Immigration Administration will issue a new visa for free on request of the visa holder after the outbreak is lifted. Some of automated border clearance systems will be shut down according to the needs of the epidemic prevention. After Wuhan declared lockdown on 23 January, the Tianhe Airport and Hankou River ports have been without passengers for several days.[249]

Since 25 January,[252] Taiwan's government banned anyone from mainland China entering the country with[240] the ban extended to mainland Chinese overseas.[253] Although the global health officials advised not to apply travel restrictions on China, the US and Australia restricted all Chinese citizens from China from entering their borders.[254] Travel restrictions were announced by Russia, Japan, Pakistan and Italy and other countries despite China's criticism of border control.[255][256]

Since 28 January, the Hong Kong government began to cut traffic down connecting mainland China.[223][257] On the same day, China's National Immigration Administration announced that with immediate effect, the application of mainland residents' visa to Hong Kong and Macau would be suspended.[258] On 3 February, Hong Kong closed most of its border to mainland China.[259][260] However, Hong Kong nurses still held a strike, demanding a complete closure.[261]

International aid

[edit]China received funds and equipment in donations from a number of other countries to help fight the pandemic.[30][31][32][262] The United Front Work Department (UFWD) also coordinated diplomatic channels, state-owned businesses and Chinese diaspora community associations in urging overseas Chinese to buy masks and send them to China. Jorge Guajardo, Mexico's former ambassador to China, suggested that "China was evidently hiding the extent of a pandemic...while covertly securing PPE at low prices", according to Global News. Guajardo called it a "surreptitious" operation that left "the world naked with no supply of PPE."[263]

China has also sent tests, equipment, experts, and vaccines to other countries to help fight the pandemic.[264][10][265] European Commissioner for Crisis Management Janez Lenarčič expressed gratitude and praised collaboration between the EU and China.[266] Chinese aid has also been well received in parts of Latin America and Africa.[267][268] Chinese-Americans also marshalled networks in China to obtain medical supplies.[269]

On 13 March, China sent medical supplies, including masks and respirators to Italy, together with a team of Chinese medical staff.[270][271] While the head of the Italian Red Cross, Francesco Rocca said these medical supplies were donated by the Chinese Red Cross,[272] there were other sources that said that these were paid products and services.[273][10] Chinese billionaire and Alibaba co-founder Jack Ma also donated 500,000 masks and other medical supplies, which landed at Liege Airport in Belgium on 13 March and then sent to Italy.[271][274] Italian Prime Minister Conte thanked China for its support and assistance.[275] A former Mexican ambassador Jorge Guajardo said that masks sent to China in January and February were being sold back to Mexico at 20 to 30 times the price.[263]

A U.S. congressional report released in April concluded that "the Chinese government may selectively release some medical supplies for overseas delivery, with designated countries selected, according to political calculations."[263]

On 18 May 2020, the Chinese government pledged US$2 billion to help other countries fight COVID-19 and to aid economic and social development "especially [in] developing countries".[227]

Equipment exports

[edit]From March through December 2020, China exported pandemic control equipment worth ¥438.5 billion (US$67.82 billion), including 224.1 billion masks, 2.31 billion other pieces of PPE clothing, 1.08 billion test kits, and 271,000 ventilators. A customs spokesperson said the mask exports were equivalent to "nearly 40 masks for everyone in the world outside China".[276]

Officials in Spain, Turkey, and the Netherlands have rejected Chinese-made equipment for being defective.[277] The Dutch Ministry of Health announced it had recalled 600,000 face masks which were made in China.[278][277] The Spanish government said they bought thousands of test kits to combat the virus, but later revealed that almost 60,000 did not produce accurate results. The Chinese embassy in Spain said that the company that made the kits was unlicensed, and that these kits were separate from the ones donated by the Chinese government.[277] The government of the United Kingdom paid two companies in China at least $20 million for test kits later found to be faulty.[279]

Discrimination

[edit]Fear, regional discrimination in China, and racial discrimination within and beyond China increased with the growing number of reported cases of infections despite calls for stopping the discrimination by many governments.[280][281] Some rumors circulated across Chinese social media, along with endorsements and counter-rumor efforts by media and governments.[282][283] The Chinese government has worked to censor and counter reporting and criticism about the crisis – which included the prosecution of several citizen journalists[221] – and portray the official response to the outbreak in a positive light. They have also provided humanitarian assistance to other countries dealing with the virus.[8][9][10] News outlets have reported concerns that the Chinese government has deliberately under-reported the extent of infections and deaths.[12][13][14]

Hubei residents

[edit]Although there has been support from Chinese online towards those in virus-stricken areas,[284] instances of regional discrimination have also arisen.[280] According to World Journal, there have been instances of Wuhan natives in other provinces being turned away from hotels, having their ID numbers, home addresses and telephone numbers deliberately leaked online or dealing with harassing phone calls from strangers. Some places also reportedly had signs saying "people from Wuhan and cars from Hubei are not welcomed here."[285] Numerous hotels, and guest houses refused entry to residents of Wuhan or kicked out residents of Hubei.[286] Multiple hotels purportedly refused a Wuhan tour guide to check in after she returned to Hangzhou from Singapore with one of them calling the police to give her a health check and asking the police to quarantine her. Amidst these incidents, various cities and prefectures outside of Hubei adopted resettlement measures for Hubei people in their region such as designated hotel accommodation for visitors from the province.[287] In Zhengding, Jingxing and Luquan of Shijiazhuang City, the local governments rewarded anyone who reported those who had been to Wuhan, but not recorded in official documents at least 1,000 yuan RMB. In Meizhou, residents reporting people entering from Hunan were awarded with 30 face masks.[288]

It was reported that on a scheduled 27 January China Southern Airlines flight from Nagoya to Shanghai, some Shanghainese travellers refused to board with 16 others from Wuhan. Two of the Wuhan travellers were unable to board due to a fever while the Shanghainese on the spot alleged that the others had taken medicine to bypass the temperature check.[285] One of the Wuhan tourists protested on Weibo, "are they really my countrymen?", to which a Shanghai tourist who was purportedly at the scene replied that they did it to protect Shanghai from the virus.[287] Many netizens criticized the Wuhan tourists for travelling with a fever, although some also called for understanding and for Shanghainese not to regionally discriminate.[289][290]

Outside mainland China

[edit]Mainland Chinese overseas have experienced discrimination and anti-Chinese sentiment during the COVID-19 outbreak.[291] In Hong Kong, a Japanese noodle restaurant said it would refuse mainland Chinese customers and said on Facebook, "We want to live longer. We want to safeguard local customers. Please excuse us."[292] In Japan, a sweet shop in Hakone and a ramen restaurant in Sapporo posted "no Chinese" signs outside.[293] Similar events were reported in South Korea.[291] The French newspaper Courrier Picard published two articles titled "Yellow Alert" and "New Yellow Peril?" which may allude to historical racist tropes about the Chinese.[293]

Beyond only Chinese, Asians in general are affected by anti-Chinese sentiment. Disinformation about Asian food and Asian communities have circulated, and videos showing Asian people eating bats have gone viral along with dehumanizing comments and implications of the cause of the virus outbreak.[294]

Africans in China

[edit]

Guangzhou has a sizeable community of black Africans including migrants, who were allegedly singled out by local authorities during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Chinese state media, five Nigerian men who had tested positive for COVID-19 broke quarantine and infected others, which triggered suspicion and anti-foreigner sentiment. In April 2020, Africans were forced to undergo coronavirus testing and quarantine, regardless of their travel history, symptoms, or contact with known patients.[295] Some restaurants – including a branch of McDonald's[296] – reportedly refused to service Africans, while landlords and hotels targeted Africans for eviction resulting in some becoming homeless.[297][298] Xinhua reported 111 Africans tested positive for the COVID-19 in Guangzhou out of a total of 4,553 tested, also saying that 19 of the cases were imported from unspecified countries.[299][300][301]

It has been noted that public sensitivity in China to racism, particularly to Africans, has been low with little education against racism or use of political correctness, while government censors appear to tolerate racism online. In the preceding few years, many Chinese believed that foreigners have been given extra benefits, leading to concerns about unfairness and inequality.[300] Many Chinese internet users soon posted racist comments, including calls for all Africans to be deported, while a cartoon depicting foreigners as different types of trash to be sorted through went viral on social media.[302]

Local media in African countries were the first to report on the issue, while Beijing initially attempted to deny such reports, calling them "rumors" or "misunderstandings" while framing it as a "wedge driving attempt" by Western media.[303] As further incidents of Africans being targeted were shared on social media, the United States Consulate General in Guangzhou warned African Americans to avoid travel to Guangzhou. The governments of Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, Kenya, and Uganda, in addition to the African Union, placed diplomatic pressure on Beijing over the incidents, and a group of African ambassadors in Beijing wrote a letter of complaint to the Chinese government about the stigmatisation and discrimination being faced by Africans.[300] The Nigerian Speaker of the House Femi Gbajabiamila showed one of the social media videos to the Chinese ambassador while the Ghanaian Minister for Foreign Affairs Shirley Ayorkor Botchway described the incidents as inhumane treatment.[302] A U.S. State Department spokesman said, "The abuse and mistreatment of Africans living and working in China is a sad reminder of how hollow the PRC-Africa partnership really is".[304]

In response to the diplomatic pressure and media coverage, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued an official statement on 12 April 2020, saying that the Chinese government attached great importance to the life and health of foreign nationals in China, has zero tolerance for discrimination, and treats all foreigners equally.[305][306] In a regular press conference on the following day, Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Zhao Lijian added that a series of new measures were adopted in Guangzhou to address the concerns of some African citizens and avoid racist and discrimination problems, while saying the United States was "making unwarranted allegations in an attempt to sow discords and stoke troubles".[307][308] China's state media later described the incidents as "small rifts", while officials made PR visits to quarantined Africans with flowers and food accompanied by television cameras, and Chinese envoys have continued to reassure their African counterparts that they would correct the misunderstandings and establish an effective communication mechanism with African Consulates-General in Guangzhou.[309][310][311] Chinese officials expressed remorse to African politicians but did not explicitly apologize, suggesting that it was largely due to "poor communication".[303]

Misinformation and conspiracy theories

[edit]There were conspiracy theories about COVID-19 being the CIA's creation to keep China down on China's Internet, according to London-based The Economist.[312]

Multiple conspiracy articles in Chinese from the SARS era resurfaced during the outbreak with altered details, claiming that SARS is biological warfare conducted by the US against China. Some of these articles claim that BGI Group from China sold genetic information of the Chinese people to the US, with the US then being able to deploy the virus specifically targeting the genome of Chinese individuals.[313]

In late January 2020, Chinese military news site Xilu published an article claiming that the virus had been artificially combined by the US to target Chinese people from the Han ethnicity, to which the large majority of Chinese belongs. The article claimed that the poor performance of US military athletes participating in the Wuhan 2019 Military World Games, which lasted until the end of October 2019, was evidence that they had in fact been "biowarfare operatives" tasked with spreading the virus.[314] The claim was later repeated on other popular sites in China.[315][316]

In March 2020, this conspiracy theory was endorsed on Twitter by Zhao Lijian, a spokesperson from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China.[317][318][319] On 13 March, the US government summoned Chinese Ambassador Cui Tiankai to Washington DC over this conspiracy theory;[320] Cui had called this theory "crazy" on Face the Nation on 9 February, and re-affirmed this belief after Zhao's tweets.[321]

In the United States, Trump administration officials, including President Donald Trump, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and others also pushed conspiracy theories repeatedly asserting that the virus had originated from a laboratory leak in Wuhan, despite widespread rejection from the scientific community and by allied intelligence.[322]

Statistics

[edit]This article needs to be updated. (December 2022) |

The case count in mainland China only includes symptomatic cases. It excludes patients who test positive but do not have symptoms, of which there were 889 as of 11 February 2020.[323] Asymptomatic infections are reported separately.[324] It is also reported that there were more than 43,000 by the end of February 2020.[325][326][327] On 17 April, following the Wuhan government's issuance of a report on accounting for COVID-19 deaths that occurred at home that went previously unreported, as well as the subtraction of deaths that were previously double-counted by different hospitals, the NHC retrospectively revised their cumulative totals dating to 16 April, adding 325 cumulative cases and 1,290 deaths.[328]

Around March 2020, there was speculation that China's COVID numbers were deliberately inaccurate, but as of 2021, China's COVID elimination strategy was considered[by whom?] to have been successful and its statistics were considered[by whom?] to be accurate.[dubious – discuss][329][330][331]

By December 2022, the Chinese central government had changed its definition of reported death statistics to only include cases in which COVID-19 directly caused respiratory failure,[332] which led to skepticism by health experts of the government's total death count.[333][334] The same month, the municipal health chief of Qingdao reported "between 490,000 and 530,000" new COVID-19 cases per day.[335]

China was part of a small group of countries such as Taiwan, Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore that pursued a zero-COVID strategy.[citation needed] The Chinese government's strategy involved extensive testing, mask wearing, temperature checks, ventilation, contact tracing, quarantines, isolation of infected people, and heavy restrictions in response to local outbreaks.

On December 25, 2022, the Chinese government's National Health Commission announced that it would no longer publish daily COVID-19 data.[336] In January 2023, the World Health Organization stated, "We believe that the current numbers being published from China under-represent the true impact of the disease in terms of hospital admissions, in terms of ICU admissions, and particularly in terms of deaths."[337]References

[edit]- ^ 新型肺炎疫情地圖 實時更新 [New pneumonia epidemic map updated in real time]. NetEase news (in Chinese). 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Sheikh, Knvul; Rabin, Roni Caryn (10 March 2020). "The Coronavirus: What Scientists Have Learned So Far". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ Khan, Natasha (9 January 2020). "New Virus Discovered by Chinese Scientists Investigating Pneumonia Outbreak". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b "China clamps down in hidden hunt for coronavirus origins". Associated Press. 30 December 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Javier C. Hernández (14 March 2020). "As China Cracks Down on Coronavirus Coverage, Journalists Fight Back". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus: Chinese app WeChat censored virus content since 1 Jan". BBC News. 4 March 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Gan, Nectar; Griffiths, James (28 December 2020). "Chinese journalist who documented Wuhan coronavirus outbreak jailed for 4 years". CNN. Archived from the original on 29 December 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Hernández, Javier C. (14 March 2020). "As China Cracks Down on Coronavirus Coverage, Journalists Fight Back". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Myers, Steven Lee (10 March 2020). "Xi Goes to Wuhan, Coronavirus Epicenter, in Show of Confidence". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Myers, Steven Lee; Rubin, Alissa J. (18 March 2020). "Its Coronavirus Cases Dwindling, China Turns Focus Outward". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ a b "China: WHO experts arriving Thursday for virus origins probe". United States: ABC News. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ a b "China accused of under-reporting coronavirus outbreak". Financial Times. London.

Health experts question the timeliness and accuracy of China's official data, saying the testing system captured only a fraction of the cases in China's hospitals, particularly those that are poorly run. Neil Ferguson, a professor of epidemiology at Imperial College London, said only the most severe infections were being diagnosed and as few as 10 per cent of cases were being properly detected, in a video released by the university.

(subscription required) - ^ a b Sobey, Rick (31 March 2020). "Chinese government lying about coronavirus could impact U.S. business ties: Experts". Boston Herald.com. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ a b "China Says It's Beating Coronavirus. But Can We Believe Its Numbers?". Time. 1 April 2020.

The move follows criticism from health experts and the U.S. and other governments that it risked a resurgence of the deadly pandemic by downplaying the number of cases within its borders.

- ^ Koch, Christoffer; Okamura, Ken (1 November 2020). "Benford's Law and COVID-19 reporting". Economics Letters. 196: 109573. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2020.109573. ISSN 0165-1765. PMC 7487520. PMID 32952242.

We find no evidence of manipulation of Chinese COVID-19 data using Benford's Law. [...] Media and politicians have cast doubt on Chinese reported data on COVID-19 cases. We find Chinese confirmed infections match the distribution expected in Benford's Law and are similar to that seen in the U.S. and Italy. [...] Contrary to popular speculation, we find no evidence that the Chinese massaged their COVID-19 statistics.

- ^ Kolias, Pavlos (2022). "Applying Benford's law to COVID-19 data: The case of the European Union". Journal of Public Health. 44 (2): e221–e226. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdac005. PMC 9234504. PMID 35325235.

Previous studies, in different fields, have applied Benford's distribution (or law) analysis to detect fraudulent and manipulated data. Specifically, for COVID-19, it was found that deaths were underreported in the USA (Campolieti, 2021), while in China no manipulation was found (Koch & Okamura, 2020).

- ^ Idrovo, Alvaro Javier; Manrique-Hernández, Edgar Fabián (May 2020). "Data Quality of Chinese Surveillance of COVID-19: Objective Analysis Based on WHO's Situation Reports". Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health. 32 (4): 165–167. doi:10.1177/1010539520927265. ISSN 1010-5395. PMC 7231903. PMID 32408808.

Was there quality in the Chinese epidemiological surveillance system during the COVID-19 pandemic? Using data of World World Health Organization's situation reports (until situation report 55), an objective analysis was realized to answer this important question. Fulfillment of Benford's law (first digit law) is a rapid tool to suggest good data quality. Results suggest that China had an acceptable quality in its epidemiological surveillance system. Furthermore, more detailed and complete analyses could complement the evaluation of the Chinese surveillance system.

- ^ Wong, Edward; Barnes, Julian E.; Kanno-Youngs, Zolan (19 August 2020). "Local Officials in China Hid Coronavirus Dangers From Beijing, U.S. Agencies Find". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ a b 时间线:武汉疫情如何一步步扩散至全球 (in Simplified Chinese). BBC News 中文. 5 February 2020. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ Wong, Maggie Hiufu (23 January 2020). "Wuhan: Inside the Chinese city at the center of the coronavirus outbreak". CNN. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Cadell, Cate; Chen, Yawen (8 April 2020). "'Painful lesson': how a military-style lockdown unfolded in Wuhan". Reuters. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Prem, Kiesha; Liu, Yang; Russell, Timothy W.; Kucharski, Adam J.; Eggo, Rosalind M.; Davies, Nicholas; Flasche, Stefan; Clifford, Samuel; Pearson, Carl A. B.; Munday, James D.; Abbott, Sam (1 May 2020). "The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: a modelling study". The Lancet Public Health. 5 (5): e261–e270. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30073-6. ISSN 2468-2667. PMC 7158905. PMID 32220655.

- ^ a b c 眾新聞 | 【武漢肺炎大爆發】西藏首宗確診 全國淪陷 內地確診累計7711宗 湖北黃岡疫情僅次武漢. 眾新聞 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b Chappell, Bill (30 January 2020). "Coronavirus Has Now Spread To All Regions of mainland China". NPR. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b c "Coronavirus declared global health emergency". BBC News. 31 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b 中国内地31省份全部启动突发公共卫生事件一级响应. Caixin. 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Yu, Xinyi (28 January 2020). 【各地在行动②】全国19省份暂停省际长途客运. People's Daily Online. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ 武汉肺炎:香港宣布大幅削减来往中国大陆交通服务 [Wuhan Pneumonia: Hong Kong Announces Significant Cuts in Transport Services to and from mainland China] (in Simplified Chinese). BBC News Chinese. 28 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Safi (now), Michael; Rourke (earlier), Alison; Greenfield, Patrick; Giuffrida, Angela; Kollewe, Julia; Oltermann, Philip (3 February 2020). "China issues 'urgent' appeal for protective medical equipment – as it happened". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Equatorial Guinea donates $2m to China to help combat coronavirus". Africanews. 5 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Feature: Japan offers warm support to China in battle against virus outbreak – Xinhua". Xinhua News Agency. 13 February 2020. Archived from the original on 10 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ a b "China's Xi Writes Thank-You Letter to Bill Gates for Virus Help". Bloomberg News. 21 February 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ "WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the mission briefing on COVID-19 – 26 February 2020". World Health Organization. 26 February 2020.

- ^ "Mainland China sees imported coronavirus cases exceed new local infections for first time". The Straits Times. 13 March 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19 and China: lessons and the way forward". The Lancet. 396 (10246): 213. 25 July 2020. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31637-8. PMC 7377676. PMID 32711779.

- ^ Cheng, Evelyn (23 December 2020). "China extends stimulus measures for small businesses – a sign the recovery is not yet complete". CNBC. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ "What are the Criteria to Determine Low, Medium and High Risk Areas? Experts: Criteria Based on Three Factors". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the People's Republic of China. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "疫情风险分区分级后,这些知识点你get到了吗?". People's Daily Online. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ a b Almond, Kyle. "Wuhan was on lockdown for 76 days. Now life is returning – slowly". CNN. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Normile, Dennis (19 November 2021). "'Zero COVID' is getting harder—but China is sticking with it". Science (journal). 374 (6570): 924. Bibcode:2021Sci...374..924N. doi:10.1126/science.acx9657. eISSN 1095-9203. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 34793217. S2CID 244403712.

- ^ Mozur, Paul; Zhong, Raymond; Krolik, Aaron (2 March 2020). "In Coronavirus Fight, China Gives Citizens a Color Code, With Red Flags". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "The Latest: China eases restrictions on domestic tourism". Associated Press. 14 July 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "China opens up domestic tourism to unleash pent up spending power". South China Morning Post. 15 July 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "China's economy continues to bounce back from virus slump". BBC News. 19 October 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "China's economic recovery continues but signals mixed in October". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Cheng, Jonathan (18 January 2021). "China Is the Only Major Economy to Report Economic Growth for 2020". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "China Says 1 Million Vaccines Given; Plans Further Rollout". Bloomberg News. 19 December 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ "China to vaccinate high-risk groups over winter and spring, health official says". CNBC. 19 December 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ Huang, Chaolin; Wang, Yeming; Li, Xingwang; Ren, Lili; Zhao, Jianping; Hu, Yi; Zhang, Li; Fan, Guohui; Xu, Jiuyang; Gu, Xiaoying; Cheng, Zhenshun (15 February 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". The Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7159299. PMID 31986264.

- ^ "China's first confirmed Covid-19 case traced back to November 17". South China Morning Post. 13 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Davidson, Helen (13 March 2020). "First Covid-19 case happened in November, China government records show—report". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Oliveira, Nelson (27 March 2020). "Shrimp vendor identified as possible coronavirus 'patient zero,' leaked document says". Daily News. New York. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Page, Jeremy; Fan, Wenxin; Khan, Natasha (6 March 2020). "How It All Started: China's Early Coronavirus Missteps". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Huang, Chaolin; Wang, Yeming; Li, Xingwang; Ren, Lili; Zhao, Jianping; Hu, Yi; Zhang, Li; Fan, Guohui; Xu, Jiuyang; Gu, Xiaoying; Cheng, Zhenshun (24 January 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". The Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7159299. PMID 31986264. S2CID 210886197.

- ^ a b c d Yu, Gao; Yanfeng, Peng; Rui, Yang; Yuding, Feng; Danmeng, Ma; Murphy, Flynn; Wei, Han; Shen, Timmy (29 February 2020). "In Depth: How Early Signs of a SARS-Like Virus Were Spotted, Spread, and Throttled". Caixin Global. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ bjnews.com.cn. "武汉疾控证实:当地现不明原因肺炎病人,发病数在统计". bjnews.com.cn. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ 武汉华南海鲜市场休市整治:多数商户已关门停业(图). January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020.

- ^ a b Strobel, Warren P. (17 January 2024). "Chinese Lab Mapped Deadly Coronavirus Two Weeks Before Beijing Told the World, Documents Show". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 17 January 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ "Previously unknown virus may be causing pneumonia outbreak in China, WHO says". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 9 January 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Khan, Natasha (9 January 2020). "New Virus Discovered by Chinese Scientists Investigating Pneumonia Outbreak". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ @who (14 January 2020). "Preliminary investigations conducted by the Chinese authorities" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "CNN Exclusive: WHO Wuhan mission finds possible signs of wider original outbreak in 2019". CNN. 14 February 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Jin, Keyu (2023). The New China Playbook: Beyond Socialism and Capitalism. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-1-9848-7828-1.

- ^ Gan, Nectar (29 December 2020). "True toll of Wuhan infections may be nearly 10 times official number, Chinese researchers say". Coronavirus. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "CPC leadership meets to discuss novel coronavirus prevention, control". People's Daily. 25 January 2020. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

Xi Jinping, general secretary of the CPC Central Committee, chaired the meeting.

- ^ "Xi says China faces 'grave situation' as virus death toll hits 42". Reuters. 26 January 2020. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "China battles coronavirus outbreak: All the latest updates". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b 多个省市启动一级响应抗击疫情,为何湖北省却不是最快的?. 第一财经 [China Business Network]. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ 自保失败 西藏武汉肺炎疑沦陷. RFI Chinese (in Simplified Chinese). 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "China virus spread is accelerating, Xi warns". BBC News. 26 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ 多地启动联防联控措施 严禁销售活禽、野生动物. Caijing (in Chinese). 23 January 2020. Archived from the original on 23 January 2020.

- ^ William Zheng and Mimi Lau (21 January 2020). "China's credibility on the line as it tries to dispel cover-up fears". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020.

Party's law and order body warns officials that anyone who tries to hide the spread of the disease will be 'nailed on the pillar of shame for eternity'

- ^ 湖北省人民政府关于加强新型冠状病毒感染的肺炎防控工作的通告. Hubei Province People's Government. 21 January 2020. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ 杨利, ed. (23 January 2020). 浙江新增新型冠状病毒感染的肺炎确诊病例17例. Provincial Health Commission of Zhejiang via The Beijing Times. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ 俞菀 (23 January 2020). 周楚卿 (ed.). 浙江:新增新型冠状病毒感染肺炎确诊病例17例 启动重大公共突发卫生事件一级响应 (in Chinese (China)). Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ 北京市启动重大突发公共卫生事件一级响应. Beijing Youth Daily. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ 上海、天津、重庆、安徽启动重大突发公共卫生事件一级响应机制. Xinhua News Agency. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ 储白珊 (24 January 2020). 福建启动重大突发公共卫生事件一级响应机制. 福建日报. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ 苏子牧 (24 January 2020). 【武汉肺炎疫情】中国14省市启动一级响应. 多维新闻. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ 防控小知识|突发公共卫生事件I级应急响应意味着什么?. 吉林电视台. 26 January 2020. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ 国务院办公厅关于延长2020年春节假期的通知. 中国政府网. 26 January 2020. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ Ding, Ke (3 February 2020). 29省发布延迟开工通知 来看各地复工具体时间及安排. 券商中国.

- ^ "Miss China Official 中国环球小姐 on Instagram: "We would like to apologize and humbly announce that due to the coronavirus, the original on-date (March 8, 2020, Lijiang, China) Miss..."". Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2020 – via Instagram.

- ^ 武汉2020春节文化旅游惠民活动延期举行. China News Service. 21 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ 倪伟 (23 January 2020). 武汉文博场馆闭馆至元宵节,全国多地博物馆取消公众活动. The Beijing Times. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ 武汉市文化和旅游局:全市所有旅游团队一律取消. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ 武汉对进出武汉人员加强管控 遏制疫情扩散. Ta Kung Pao. 21 January 2020.

- ^ 北京龙潭、地坛庙会取消. Beijing Youth Daily. 23 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ 北京宣布即日起取消包括庙会在内的大型活动. Beijing Daily. 23 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ 北京故宫恭王府世纪坛宣布明日起暂停开放. The Beijing Times. 23 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ 国家海洋博物馆 (24 January 2020). 关于国家海洋博物馆暂停试运行开放的公告.

- ^ 应妮 (23 January 2020). 郭泽华 (ed.). 故宫博物院发布闭馆公告 中国多地取消新春文化活动. China News Service (in Chinese (China)). Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ 西湖景区收费景点、博物馆明起全部关闭 游船、喷泉暂停. 浙江新闻客户端. 23 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ 苏湘洋 (24 January 2020). 南京秦淮灯会多个展区即日起闭园. 現代快報. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ 葉琪 (24 January 2020). 【武漢肺炎】全國多地旅遊景區關閉防疫 上海迪士尼年初一起關閉. HK01. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ 腾讯体育_新型冠状病毒席卷武汉 女足奥预赛易地南京举行. n.d. Archived from the original on 22 January 2020.

- ^ 女足将隔离备战奥预赛 王珊珊回归盼解锋无力难题. Sina Sports. 27 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ 中国足协延期举行超级杯 中超联赛或将同样延期. 中新社 (in Chinese). 25 January 2020. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus affects AFC Champions League". ESPN. 25 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ 中国足协延期开始2020赛季全国各级各类足球比赛. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ "AFC calls for emergency meetings with National and Club representatives (Updated)". Asian Football Confederation. 28 February 2020.

- ^ 受武汉疫情影响 东京奥运会拳击预选赛被终止. Sina Sports. 22 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ 东京奥运拳击项目武汉站资格赛取消. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ 东京奥运会拳击资格赛将从武汉改至约旦安曼举行. Sina Sports. 26 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ 女篮奥运资格赛因疫情易地,中国队失去主场优势. The Beijing Times. 27 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ 室内田径世锦赛因疫情推迟1年 田联仍交由南京举办. 163.com Sports. 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ 受疫情影响 网球联合会杯从东莞改至哈萨克进行. 163.com Sports. 26 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ 体育总局:防控疫情,取消举办体育六艺系列活动之乐动冰雪_中国政库_澎湃新闻-The Paper. Thepaper.cn. n.d. Archived from the original on 23 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ 防控疫情:2020年中国长白山冰雪汽车拉力赛暂停举办. 澎湃新闻. n.d. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ WCBA后续赛事延迟,中国排协暂停一切排球赛事和活动. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ "Formula E postpones China race amid virus outbreak". motorsport.com. 2 February 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ "2020 F1 Chinese Grand Prix postponed due to novel coronavirus outbreak | Formula One". Formula One. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ "BWF Statement on Postponement of Lingshui China Masters". bwfbadminton.com. Badminton World Federation. 1 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ 受疫情影响 第14届全国冬季运动会将推迟举办. 163.com Sports. 26 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ 人民日报 (21 January 2020). 武汉新东方、新航道、学而思等校外培训机构停课防疫. 新浪财经_新浪网. Archived from the original on 23 January 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ 湖北:全省学校推迟开学时间 党政机关出差取消. Xinhua News Agency. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ 浙江省教育厅紧急通知!切实做好新型冠状病毒感染的肺炎疫情防控工作. 浙江在线. 22 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ 深圳即日起停止校外培训机构春节假期补课,何时复课等官方通知. n.d. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020.

- ^ 关于2019-2020学年寒假延期的通知-上海大学. n.d. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020.

- ^ 教育部发布2020年春季学期延期开学的通知. 央视新闻客户端 (in Chinese). 27 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ 人社部:全国技工院校2020年春季学期延期开学. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ 雅思官微:取消在武汉的2月8日、13日及20日雅思考试_教育家_澎湃新闻-The Paper. Thepaper.cn. n.d. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ 教育部考试中心:取消2月所有托福、雅思考试. bjd.com.cn. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ 教育部:留学人员无特殊需要建议推迟出境时间-中新网. chinanews.com. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ 国家公务员局:国考面试时间推迟. 人民日报客户端 (in Chinese (China)). 28 January 2020. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ 陈咏 (25 January 2020). 扬州取消2月2日结婚登记. 扬子晚报 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 25 January 2020.

- ^ 徐俊勇 (25 January 2020). 甘肃省取消2 February 2020 结婚登记办理. 甘肃日报 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 26 January 2020.

- ^ 苏赞 (25 January 2020). 广州取消2 February 2020 婚姻登记工作. 广州日报 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 25 January 2020.

- ^ 上海因防疫取消2月2日结婚登记办理. 星洲日报 (in Chinese). 25 January 2020. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020.

- ^ 民政部:建议取消2月2日开放婚姻登记. 人民日报客户端 (in Chinese). 31 January 2020.

- ^ Parke, Caleb (23 March 2020). "In coronavirus fight, China hasn't stopped persecuting Christians: watchdog". Fox News. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Klett, Leah MarieAnn (21 March 2020). "China demolishes church, removes crosses as Christians worship at home". The Christian Post. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ 防控疫情 浙江宁波"两会"推迟召开. Caixin. 9 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ "China parliament may delay key annual March session: Xinhua". Reuters. 17 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ "China may delay annual meeting of parliament due to virus outbreak: sources". Reuters. 6 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.