Brookhaven, Mississippi

Brookhaven, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

Brookhaven City Hall | |

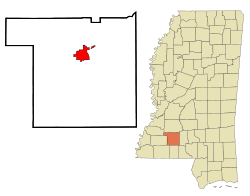

Location of Brookhaven, Mississippi | |

| Coordinates: 31°34′55″N 90°26′35″W / 31.58194°N 90.44306°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Lincoln |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Joe Cox |

| Area | |

| • Total | 21.73 sq mi (56.28 km2) |

| • Land | 21.64 sq mi (56.05 km2) |

| • Water | 0.09 sq mi (0.23 km2) |

| Elevation | 489 ft (149 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 11,674 |

| • Density | 539.41/sq mi (208.27/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 39601-39603 |

| Area code | 601 |

| FIPS code | 28-08820 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0667590 |

| Website | brookhaven-ms |

Brookhaven is a small city in Lincoln County, Mississippi, United States, 55 miles (89 km) south of the state capital of Jackson. The population was 11,674 people at the 2020 U.S. Census.[2] It is the county seat of Lincoln County.[3] It was named after the town of Brookhaven, New York, by founder Samuel Jayne in 1818.

History

[edit]

Brookhaven is located in what was formerly territory of the Choctaw. The city was founded in 1818 by Samuel Jayne from New York, who named it after the town of Brookhaven on Long Island.[4] Most of the Choctaw were forced out of Mississippi in the 1830s under Indian Removal, and were given lesser land in Indian Territory.

The railroad was constructed through Brookhaven in 1858.[4] It connected Brookhaven with New Orleans to the south and Memphis to the north.

During the Civil War, Brookhaven was briefly occupied at noon on April 29, 1863, by a raiding party of Union cavalry under the command of Colonel Benjamin Grierson. The Union force burned public buildings and destroyed the railroad.[5] This was rebuilt after the war.

In 1908, a mob of 2,000 White people assaulted a military guard and kidnapped a Black man, Eli Pigot, and murdered him in broad daylight.[6]

In 1936 Brookhaven was chosen as the site of the Stahl-Urban garment plant.[7]

In 1955, Lamar Smith, a black farmer and World War I veteran, was shot to death by whites mid-day on the lawn of the county courthouse in Brookhaven.[8] He had been working to organize voter registration among blacks, who had been largely disenfranchised in the state since 1890 by barriers created by whites. After World War II, Smith was among the many veterans who became activists for civil rights, determined to regain their constitutional rights. Nobody was prosecuted for his murder.[8]

In 2022, D'Monterrio Gibson, a black FedEx driver was chased down and shot at by two white men after Gibson had delivered a package to an incorrect address and then retrieved it.[9][10]

Geography

[edit]Brookhaven is in central Lincoln County. Interstate 55 passes through the west side of the city, with access from Exits 38, 40, and 42. I-55 leads north 55 miles (89 km) to Jackson, the state capital, and south 79 miles (127 km) to Hammond, Louisiana. U.S. Route 51 runs parallel to I-55, passing through the west side of Brookhaven closer to the city center. US-51 leads north 20 miles (32 km) to Hazlehurst and south 25 miles (40 km) to McComb. U.S. Route 84 passes through the south side of Brookhaven, leading east 36 miles (58 km) to Prentiss and west 61 miles (98 km) to Natchez.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 21.7 square miles (56.3 km2), of which 21.7 square miles (56.1 km2) are land and 0.1 square miles (0.2 km2), or 0.41%, are water.[11] The city expanded in late 2007 to almost triple its previous area, through a vote of annexation, to bring in suburban developments surrounding the older town and equalize taxing and services provided to the new metropolitan area.[12][13]

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Brookhaven, Mississippi (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 85 (29) |

86 (30) |

92 (33) |

96 (36) |

102 (39) |

106 (41) |

109 (43) |

106 (41) |

106 (41) |

99 (37) |

89 (32) |

87 (31) |

109 (43) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 57.2 (14.0) |

61.6 (16.4) |

68.6 (20.3) |

75.0 (23.9) |

82.0 (27.8) |

87.6 (30.9) |

89.7 (32.1) |

90.1 (32.3) |

86.0 (30.0) |

77.5 (25.3) |

66.8 (19.3) |

59.4 (15.2) |

75.1 (23.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 46.7 (8.2) |

50.6 (10.3) |

57.3 (14.1) |

63.7 (17.6) |

71.7 (22.1) |

78.0 (25.6) |

80.3 (26.8) |

80.2 (26.8) |

75.6 (24.2) |

65.3 (18.5) |

55.0 (12.8) |

48.9 (9.4) |

64.4 (18.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 36.1 (2.3) |

39.6 (4.2) |

46.0 (7.8) |

52.3 (11.3) |

61.3 (16.3) |

68.5 (20.3) |

70.8 (21.6) |

70.3 (21.3) |

65.2 (18.4) |

53.2 (11.8) |

43.2 (6.2) |

38.5 (3.6) |

53.8 (12.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 2 (−17) |

−10 (−23) |

14 (−10) |

26 (−3) |

38 (3) |

44 (7) |

54 (12) |

54 (12) |

37 (3) |

25 (−4) |

17 (−8) |

5 (−15) |

−10 (−23) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.52 (166) |

5.88 (149) |

5.71 (145) |

5.84 (148) |

4.44 (113) |

4.57 (116) |

5.71 (145) |

5.14 (131) |

4.30 (109) |

3.64 (92) |

4.19 (106) |

5.64 (143) |

61.58 (1,564) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.8 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 6.5 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 10.3 | 8.5 | 6.5 | 5.7 | 6.9 | 9.1 | 98.5 |

| Source: NOAA[14][15] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 996 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,614 | 62.0% | |

| 1880 | 1,615 | 0.1% | |

| 1890 | 2,142 | 32.6% | |

| 1900 | 2,678 | 25.0% | |

| 1910 | 5,293 | 97.6% | |

| 1920 | 4,706 | −11.1% | |

| 1930 | 5,288 | 12.4% | |

| 1940 | 6,232 | 17.9% | |

| 1950 | 7,801 | 25.2% | |

| 1960 | 9,885 | 26.7% | |

| 1970 | 10,700 | 8.2% | |

| 1980 | 10,800 | 0.9% | |

| 1990 | 10,243 | −5.2% | |

| 2000 | 9,861 | −3.7% | |

| 2010 | 12,513 | 26.9% | |

| 2020 | 11,674 | −6.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 4,439 | 38.02% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 6,710 | 57.48% |

| Native American | 15 | 0.13% |

| Asian | 117 | 1.0% |

| Pacific Islander | 2 | 0.02% |

| Other/Mixed | 266 | 2.28% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 125 | 1.07% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 11,674 people, 4,346 households, and 2,827 families residing in the city.

2010 census

[edit]As of the 2010 census,[17] there were 12,513 people, 4,768 households, and 3,146 families residing in the city of Brookhaven. The population density was 1,714.1 inhabitants per square mile (661.8/km2). There were 5,519 housing units at an average density of 756.0 per square mile (291.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was fairly evenly split with 43.8% White, 54.1% African American, 0.1% Native American, 0.7% Asian, 0.2% from other races, and 1.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.9% of the population.

There were 4,768 households, out of which 34.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.7% were married couples living together, 24.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.0% were non-families. 30.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.48 and the average family size was 3.10.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 26.4% under the age of 18, 5.5% from 20 to 24, 29.2% from 25 to 44, 25.3% from 45 to 64, and 16.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37.6 years.

The median income for a household in the city was $30,036, and the median income for a family was $40,018. About 25.2% of families and 31.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 46.6% of those under age 18 and 16.0% of those age 65 or over.

Education

[edit]The city is served by the Brookhaven School District of public schools. Up until 1970, separate systems were maintained for black students and white schools. When Brown v. Board required integration of schools in 1954, white citizens refused. In 1970, when the state finally capitulated and desegregated public schools, a private school, Brookhaven Academy, was created to allow white parents to keep their children from attending schools with black children.

In 1988, Brookhaven High School hired a football coach, Hollis Rutter, from Brookhaven Academy. This so upset the black population, who felt that this was a racially-insensitive move, that a school boycott ensued, ultimately resulting in the rescission of Rutter's hiring. This school again came into the spotlight in 2018 when it became known that Cindy Hyde-Smith, a candidate for U.S. Senate known for making racially-incendiary statements, sent her daughter to this school.[18][19]

The statewide magnet high school, the Mississippi School of the Arts is also located in the city. Four Lincoln County public schools are also located in Brookhaven's rural areas: Bogue Chitto Attendance Center, Enterprise Attendance Center, Loyd Star Attendance Center and West Lincoln Attendance Center. The former institution of higher learning Whitworth Female College, founded in 1858, was located in Brookhaven. The all-girls college closed its doors in 1984.[20]

In 2019, it was reported that the school district still "has largely segregated classrooms – some all-black, some majority white."[21]

Media

[edit]Brookhaven is a part of the Jackson, Mississippi television market, including news stations WLBT, WJTV, WAPT, and WDBD. The city is served by a daily newspaper called The Daily Leader.

Infrastructure

[edit]Roads

[edit]Brookhaven contains Interstate 55 and U.S. Route 51, which run parallel to each other going north-south, and U.S. Route 84, which runs east-west.

Rail transportation

[edit]Amtrak's famous City of New Orleans (subject of the song ballad written by Steve Goodman and recorded by folk singer Arlo Guthrie in 1972) serves Brookhaven, going north and south on the old Illinois Central and Gulf, Mobile and Ohio railroad lines.

Notable people

[edit]- Lance Dwight Alworth, American football player

- Elsie Barge, pianist, music educator, and clubwoman

- Jim C. Barnett, physician and surgeon; member of the Mississippi House of Representatives from 1992 to 2008.[22]

- Jim Brewer, Maxwell Street blues musician

- Corey Dickerson, baseball player

- Bernard Ebbers, former CEO of WorldCom

- Charles Henri Ford, poet, novelist, filmmaker, photographer, and collage artist[23]

- Ruth Ford, actress

- Cindy Hyde-Smith, U.S. Senator from Mississippi

- Earsell Mackbee, football player

- Garry Owen, film actor

- Robert W. Pittman, founder MTV and former CEO and COO of AOL[24]

- Lulah Ragsdale, poet, novelist, actor

- David Banner, rapper

- Richard Scruggs, lawyer

- J. Kim Sessums, artist[25]

- Lamar Smith, Civil rights activist.[26]

- Guy Turnbow, football player[27]

- Addie L. Wyatt, leader in the United States Labor movement, civil rights activist, and Time magazine as Person of the Year in 1975.[28]

Architecture

[edit]Brookhaven's Temple B'nai Shalom is an example of Moorish Revival architecture.

References

[edit]- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ a b "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 17, 2021.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Brookhaven, Mississippi.

- ^ Grabau, Warren (2000). Ninety-Eight Days: A Geographer's View of the Vicksburg Campaign. Knoxville: University of Tennessee. p. 116. ISBN 1-57233-068-6.

- ^ "Two thousand citizens hang woman's assailant". Daily Times. Chattanooga, Tennessee. p. 3.

- ^ Stahl-Urban Photograph Collection Archived 2015-09-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Payne, Charles M. (1996). I've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. University of California Press. p. 39. ISBN 9780520207066.

- ^ Bella, Timothy (February 11, 2022). "Father and son charged with shooting at Black FedEx driver in case echoing Arbery's killing". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ Zaru, Deena; Ross, Kendall; Ghebremedhin, Sabina (February 13, 2022). "2 white men charged after allegedly chasing, shooting at Black FedEx driver". ABC News. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Gazetteer Files: 2019: Places: Mississippi". U.S. Census Bureau Geography Division. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ BrookhavenMS.org Archived October 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Brookhaven, MS (BRH) — Great American Stations

- ^ "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 15, 2023.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 15, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- ^ Pittman, Ashton (November 23, 2018). "Hyde-Smith Attended All-White 'Seg Academy' to Avoid Integration". Jackson Free Press. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith attended and graduated from a segregation academy that were set up so that white parents could avoid having to send their children to schools with black students, a yearbook reveals.

- ^ Campbell, Donna (May 9, 2017). [Governor to speak at BA graduation "Governor to speak at BA graduation"]. The Daily Leader. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

Anna-Michael Smith is one of 34 graduates who will be receiving diplomas in John R. Gray Gymnasium at BA Friday. The ceremony begins at 7 p.m. and it is open to the public. mith is the daughter of Mike Smith and Cindy Hyde-Smith, of Brookhaven. Her mom is the commissioner of agriculture and commerce for the state. The Smiths also raise cattle, which makes Anna-Michael a fifth generation farmer.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Patti Carr Black; Marion Barnwell (2002). Touring Literary Mississippi. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-57806-367-3.

- ^ Northam, Adam. "63 years after landmark Brown v. Board case, segregated classrooms persist". USA TODAY. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- ^ "Longtime Legislator Barnett Dies at 86, July 29, 2013". Jackson Free Press. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- ^ 'Charles Henri Ford 94, Prolific Poet, Artist and Editor,' The New York Times, Roberta Smith, September 30, 2002

- ^ Munk, Nina (2004). Fools Rush In: Steve Case, Jerry Levin, and the Unmaking of AOL Time Warner. New York: Harper Collins. pp. 89–92. ISBN 0-06-054035-4.

- ^ "State Resolution #15 of 2004 Session" (PDF). Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ^ "Three Recent Murders". Pittsburgh Courier. December 10, 1955.

- ^ "GUY TURNBOW". profootballarchives.com. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved October 9, 2015.

- ^ "A Dozen Who Made a Difference – Alison Cheek: Bold Unionist". Time. January 5, 1976. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2008.