May Thirtieth Movement

| Part of a series on the |

| Chinese Communist Revolution |

|---|

|

| Outline of the Chinese Civil War |

|

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

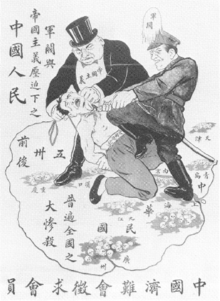

The May Thirtieth Movement (simplified Chinese: 五卅运动; traditional Chinese: 五卅運動; pinyin: Wǔsà Yùndòng) was a major labor and anti-imperialist movement during the middle-period of the Republic of China era. It began when the Shanghai Municipal Police opened fire on Chinese protesters in Shanghai's International Settlement on 30 May 1925 (the Shanghai massacre of 1925). The shootings sparked international censure and nationwide anti-foreign demonstrations and riots[1] such as the Hands Off China protests in the United Kingdom.

Background

[edit]In the aftermath of the 1924 Second Zhili–Fengtian War, China found itself in the midst of one of the most destructive periods of turmoil since 1911.[2] The war had involved every major urban area in China, and badly damaged the rural infrastructure. As a result of the conflict the Zhili-controlled government, backed by varied Euro-American business interests, was ousted from power by pro-Japanese warlord Zhang Zuolin, who installed a government led by the generally unpopular statesman Duan Qirui in November 1924. Though victorious, the war left Zhang's central government bankrupt and Duan exercised little authority outside Beijing. Authority in the north of the country was divided between Zhang and Feng Yuxiang, a Soviet Union-backed warlord, and public support for the northern militarists soon hit an all-time low, with southerners openly disparaging provincial governors as junfa (warlords).[2] With his monarchist leanings and strong base in conservative Manchuria, Zhang represented the far right in Chinese politics and could claim few supporters. Meanwhile, the KMT (Nationalist) and Communist parties (allied as the First United Front) were running a diplomatically unrecognized Soviet-backed administration in the southern province of Guangdong.[citation needed]

Alongside public grief at the recent death of China's Republican hero Sun Yat-sen (12 March 1925), the KMT sought to foment pro-Chinese, anti-imperial, and anti-Western organizations and propaganda within major Chinese cities.[3] Chinese Communist Party (CCP) groups were particularly involved in sowing dissent in Shanghai through the far-left Shanghai University. Shanghai's native Chinese were strongly unionised compared to other cities and better educated, and recognised their plight as involving lack of legal factory inspection, recourse for worker grievances or equal rights.[4] Many Chinese families were also aggrieved by an upcoming Child Employment Bill, proposed by the Shanghai Municipal Council, that would have stopped children under the age of 12 from working in mills and factories (many working-class homes relied on wages brought in by children). Educated Chinese were also offended by the council's plan to introduce a new censorship law, forcing all publications in the Settlement to use the publisher's true name and address.[citation needed]

In early months of 1925, conflicts and strikes on those matters intensified. Japanese-owned cotton mills were a source of contention, and fights and demonstrations between Japanese and Chinese employees around the #8 Cotton Mill became regular occurrences. In February, a group of Japanese managers were attacked while leaving work and one of them was killed. In response, Japanese foremen took to carrying pistols while on duty. The escalation of ill-feeling culminated on 15 May, when during a violent Neo-Luddite-style riot inside the mill, a Japanese foreman shot dead a demonstrator named Ku Cheng-Hung (顾正红; pinyin : gù zhèng-hóng).[5] Over the following weeks Ku Chen-Hung became viewed as a martyr by Chinese unions and student groups (though not by the Chinese authorities or the middle-class, who noted his political affiliations and close family membership to a prominent criminal gang). Numerous protests and strikes subsequently began against Japanese-run industries.[citation needed]

A week later a group of Chinese students, heading for Ku's public "state" funeral and carrying banners, were arrested while traveling through the International Settlement. With their trial set for 30 May, various student organisations convened in the days before and decided to hold mass demonstrations across the International Settlement and outside the Mixed Court.[citation needed]

The Nanjing Road incident

[edit]

On the morning of 30 May 1925, just after the trial of the arrested students began, Shanghai Municipal Police arrested 15 ringleaders of a student protest being held on and around Nanking Road, in the foreign controlled International Settlement. The protesters were held in Louza (Laozha) police station, which by 2:45 pm was facing a "huge crowd" of Chinese that had amassed outside. The demonstrators demanded the arrested ringleaders be returned to them and in a number of cases entered the police station, where (according to SMP officers) they tried to either block the foyer or gain access to the cells. Police on Nanking Road reported the crowd, which was between 1,500 and 2,000 strong, started good-naturedly but became more aggressive as arrests were made.[citation needed]

After forcing protesters out of the charge room, a picket of police (there was only a skeleton staff of approximately two dozen officers overall, predominantly Sikh and Chinese, with three white officers) was set up to prevent demonstrators from entering the station. In the minutes before the shooting, police and some witnesses reported that cries of "kill the foreigners" were raised as the demonstration turned violent.[6][7] Inspector Edward Everson, station commander and the highest-ranking officer on the scene (as the police commissioner K.J. McEuen had not let early warnings of public demonstrations interfere with his attendance at the city's Race Club) eventually shouted, "Stop! If you do not stop I will shoot!" in Wu. A few seconds later, at 3:37 pm, and as the crowd was within six feet of the station entrance, he fired into the crowd with his revolver. The Sikh and Chinese policemen then also opened fire, discharging some 40 rounds. At least four demonstrators were killed at the scene, with another five dying later of their injuries. At least 14 injured were hospitalized, with many others wounded.[8]

Strikes and martial law

[edit]On Sunday, 31 May, crowds of students posted bills and demanded shops refuse to sell foreign goods or serve non-Chinese. They then convened at the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, where they gave a list of demands, including punishment of the officers involved in the shooting, an end to extraterritoriality and closure of the Shanghai International Settlement. The president of the Chamber of Commerce was away, but eventually his deputy agreed to press for the demands to be carried out. Nevertheless, he subsequently sent a message to the foreign Municipal Council that his consent was given under duress.

The Municipal Council declared a state of martial law on Monday, 1 June, calling up the Shanghai Volunteer Corps militia and requesting foreign military assistance to carry out raids and protect vested interests. Over the next month Shanghai businesses and workers went on strike, and there were sporadic outbreaks of demonstration and violence. Trams and foreigners were attacked, and there was looting of shops that refused to uphold the boycott of foreigners. Servants to foreigners refused to work, and almost a third of Chinese police failed to turn up for their shifts. The gas works, electricity station, waterworks and telephone exchange became entirely run by Western volunteers.

The numbers of Chinese killed and injured in the 30 May Movement's riots vary: figures normally vary between 30 and 200 dead, with hundreds injured. Policemen, firemen and foreigners were also injured, some seriously, and one Chinese police constable was killed.

Aftermath

[edit]The incident shocked and galvanized China, and the strikes and boycotts, coupled with further violent demonstrations and riots, quickly spread across the country, bringing foreign economic interests to a near standstill.[9] The 15 "ringleaders" originally arrested on 30 May were given light or suspended sentences by Shanghai's foreign-run Mixed Court.

The target of public ire moved from the Japanese (for the death of Ku Chen-Hung) to the British, and Hong Kong was particularly affected (the strikes were there known as the Canton-Hong Kong strike).[8] Further shootings by foreigners upon Chinese protesters occurred at Canton, Mukden and elsewhere, although a reported incident at Nanking that became a cause célèbre for anti-imperialists was apparently carried out by local Chinese authorities. Indeed, the Chinese warlords used the incident as a pretext to further their own political aims. While Feng Yuxiang threatened to attack British interests via force and demanded a public apology, Zhang Zuolin, who effectively controlled Shanghai's Chinese outskirts, had his police and soldiers arrest protesters and Communists and assist the Settlement forces.[citation needed]

Two investigations into the events of 30 May were ordered, one by Chinese authorities and one by international appointees, Justice Finley Johnson (presiding), Judge of the Court of First Instance in the Philippines (representing America), Sir Henry Gollan, Chief Justice of Hong Kong (representing Britain) and Justice Kisaburo Suga of the Hiroshima Court of Appeal (representing Japan). The Chinese authorities refused to participate in the international investigation, which found 2-1 that the shooting justifiable. Only the Justice Finley from America disagreed and recommended sweeping changes, including the retirement of the chief of the Settlement Police, Commissioner McEuen, and Inspector Everson. Their forced resignation in late-1925 would be the only official result of the inquiry.[citation needed]

By November, with Chiang Kai-shek having finally wrested power from his rivals after Sun Yat-sen's death and with Chinese businesses wishing to return to operation (the Settlement had begun cutting electricity to Chinese mills), the strikes and protests began to fizzle out.[6] In Hong Kong, however, they would not totally end until mid-1926. The Kuomintang's support for the movement, and its Northern Expedition of 1926–27, eventually led to reforms in the governance of the International Settlement's Shanghai Municipal Council and the beginning of the removal of the Unequal Treaties.[citation needed]

The May Thirtieth events caused the transfer of the Muslim Chengda College and Imam (Ahong) Ma Songting to Beijing.[10]

The May Thirtieth Movement began a period of increasing radicalization and militancy among China's industrial workers, students, and progressive intellectuals.[11]: 61 It resulted in a major period of growth for the CCP.[12]: 56 It also helped boost the Kuomintang to national hegemony.[12]: 56

Memorial

[edit]In the 1990s, the May Thirtieth Movement Monument was installed at People's Park.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- History of the Republic of China

- May Fourth Movement

- Republic of China Armed Forces

- Shanghai massacre

- Warlord Era

References

[edit]- ^ Cathal J. Nolan (2002). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of International Relations: S-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1509. ISBN 978-0-313-32383-6.

- ^ a b Waldron, Arthur, (1991) From War to Nationalism: China's Turning Point, p. 5.

- ^ Ku, Hung-Ting [1979] (1979). Urban Mass Movement: The May Thirtieth Movement in Shanghai. Modern Asian Studies, Vol.13, No.2. pp.197-216

- ^ B.L [1936] (Jul 15, 1936). Shanghai at Last Gets Factory Inspection Law. Far Eastern Survey, Vol.5, No.15.

- ^ Ku, Hung-Ting [1979] (1979). Urban Mass Movement: The May Thirtieth Movement in Shanghai. Modern Asian Studies, Vol.13, No.2. pp.201

- ^ a b Potter, Edna Lee (1940). News Is My Job: A Correspondent in War-Torn China. Macmillan publishing. p. 198

- ^ Bickers, Robert [2003] (2003). Empire Made Me: An Englishman Adrift in Shanghai. Allen Lane publishing. ISBN 0-7139-9684-6. p. 165

- ^ a b Carroll, John Mark Carroll. [2007] (2007). A concise history of Hong Kong. Rowman & Littlefield publishing. ISBN 0-7425-3422-7, ISBN 978-0-7425-3422-3. p. 100

- ^ http://www.yalebooks.co.uk/yale/results.asp?SF1=author&ST1=Niv%20Horesh&. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)[dead link] - ^ Jonathan Neaman Lipman (1 July 1998). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. University of Washington Press. pp. 176–. ISBN 978-0-295-80055-4.

- ^ Qian, Ying (2024). Revolutionary Becomings: Documentary Media in Twentieth-Century China. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231204477.

- ^ a b Crean, Jeffrey (2024). The Fear of Chinese Power: an International History. New Approaches to International History series. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-350-23394-2.