Qatar

State of Qatar | |

|---|---|

| Motto: الله الوطن الأمير Allāh al-Waṭan al-ʾAmīr "God, Nation, Emir" | |

| Anthem: السلام الأميري As-Salām al-ʾAmīrī "Peace to the Emir" | |

Location and extent of Qatar (dark green) on the Arabian Peninsula | |

| Capital and largest city | Doha 25°18′N 51°31′E / 25.300°N 51.517°E |

| Official languages | Arabic[1] |

| Ethnic groups (2019)[3] |

|

| Religion (2020)[4] | |

| Demonym(s) | Qatari |

| Government | Unitary authoritarian[5][6] parliamentary semi-constitutional monarchy |

• Emir | Tamim bin Hamad |

• Deputy Emir | Abdullah bin Hamad |

| Mohammed bin Abdulrahman | |

| Legislature | Consultative Assembly |

| Establishment | |

| 18 December 1878 | |

• Declared independence | 1 September 1971 |

• Independence from the United Kingdom | 3 September 1971 |

| Area | |

• Total | 11,581 km2 (4,471 sq mi) (158th) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 2,795,484[7] (139th) |

• 2010 census | 1,699,435[8] |

• Density | 176/km2 (455.8/sq mi) (76th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2007) | 41.1[10] medium |

| HDI (2022) | very high (40th) |

| Currency | Qatari riyal (QAR) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (AST) |

| Driving side | right[12] |

| Calling code | +974 |

| ISO 3166 code | QA |

| Internet TLD | |

Qatar[a] (Arabic: قطر Qaṭar)[b] officially the State of Qatar,[c] is a country in West Asia. It occupies the Qatar Peninsula on the northeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in the Middle East; it shares its sole land border with Saudi Arabia to the south, with the rest of its territory surrounded by the Persian Gulf. The Gulf of Bahrain, an inlet of the Persian Gulf, separates Qatar from nearby Bahrain. The capital is Doha, home to over 80% of the country's inhabitants, and the land area is mostly made up of flat, low-lying desert.

Qatar has been ruled as a hereditary monarchy by the House of Thani since Mohammed bin Thani signed "an agreement, not a formal treaty"[18] with Britain in 1868 that recognised its separate status. Following Ottoman rule, Qatar became a British protectorate in 1916 and gained independence in 1971. The current emir is Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, who holds nearly all executive, legislative, and judicial authority in autocratic manner under the Constitution of Qatar.[19] He appoints the prime minister and cabinet. The partially-elected Consultative Assembly can block legislation and has a limited ability to dismiss ministers.

In early 2017, the population of Qatar was 2.6 million, although only 313,000 of them are Qatari citizens and 2.3 million being expatriates and migrant workers.[20] Its official religion is Islam.[21] The country has the fourth-highest GDP (PPP) per capita in the world[22] and the eleventh-highest GNI per capita (Atlas method).[23] It ranks 42nd in the Human Development Index, the third-highest HDI in the Arab world.[24] It is a high-income economy, backed by the world's third-largest natural gas reserves and oil reserves.[25] Qatar is one of the world's largest exporters of liquefied natural gas[26] and the world's largest emitter of carbon dioxide per capita.[27]

In the 21st century, Qatar emerged as both a major non-NATO ally of the United States and a middle power in the Arab world. Its economy has risen rapidly through its resource-wealth,[28][29] and its geopolitical power has risen through its media group, Al Jazeera Media Network, and reported support for rebel groups financially during the Arab Spring.[30][31][32] Qatar also forms part of the Gulf Cooperation Council.[3]

Etymology

Pliny the Elder, a Roman writer, documented the earliest account pertaining to the inhabitants of the peninsula around the mid-first century AD, referring to them as the Catharrei, a designation that may have derived from the name of a prominent local settlement.[33][34] A century later, Ptolemy produced the first known map to depict the peninsula, referring to it as Catara.[34][35] The map also referenced a town named "Cadara" to the east of the peninsula.[36] The term "Catara" (inhabitants, Cataraei)[37] was exclusively used until the 18th century, after which "Katara" emerged as the most commonly recognised spelling.[36] Eventually, after several variations—"Katr", "Kattar" and "Guttur"—the modern derivative Qatar was adopted as the country's name.[38] In Standard Arabic, the name is pronounced [ˈqɑtˤɑr], while in the local dialect it is [ˈɡɪtˤɑr].[17] English speakers use different approximate pronunciations of the name as the Arabic pronunciations use sounds not often used in English.[39]

History

Antiquity

Human habitation in Qatar dates back to 50,000 years ago.[40] Settlements and tools dating back to the Stone Age have been unearthed in the peninsula.[40] Mesopotamian artifacts originating from the Ubaid period (c. 6500–3800 BC) have been discovered in abandoned coastal settlements.[41] Al Da'asa, a settlement located on the western coast of Qatar, is the most important Ubaid site in the country and is believed to have accommodated a small seasonal encampment.[42][43]

Kassite Babylonian material dating back to the second millennium BC found in Al Khor Islands attests to trade relations between the inhabitants of Qatar and the Kassites in modern-day Bahrain.[44] Among the findings were crushed snail shells and Kassite potsherds.[42] It has been suggested that Qatar is the earliest known site of shellfish dye production, owing to a Kassite purple dye industry which existed on the coast.[41][45]

In 224 AD, the Sasanian Empire gained control over the territories surrounding the Persian Gulf.[46] Qatar played a role in the commercial activity of the Sasanids, contributing at least two commodities: precious pearls and purple dye.[47] Under the Sasanid reign, many of the inhabitants in eastern Arabia were introduced to Christianity following the eastward dispersal of the religion by Mesopotamian Christians.[48] Monasteries were constructed and further settlements were founded during this era.[49][50] During the latter part of the Christian era, Qatar comprised a region known as 'Beth Qatraye' (Syriac for "house of the Qataris").[51] The region was not limited to Qatar; it also included Bahrain, Tarout Island, Al-Khatt, and Al-Hasa.[52]

In 628, the Islamic prophet Muhammad sent a Muslim envoy to a ruler in eastern Arabia named Munzir ibn Sawa Al-Tamimi and requested that he and his subjects accept Islam. Munzir obliged his request, and accordingly most of the Arab tribes in the region converted to Islam.[53] In the middle of the century, the Muslim conquest of Persia resulted in the fall of the Sasanian Empire.[54]

Early and late Islamic period (661–1783)

Qatar was described as a famous horse and camel breeding centre during the Umayyad period.[55] In the 8th century, it started benefiting from its commercially strategic position in the Persian Gulf and went on to become a centre of pearl trading.[56][57] Substantial development in the pearling industry around the Qatari Peninsula occurred during the Abbasid era.[55] Ships voyaging from Basra to India and China would make stops in Qatar's ports during this period. Chinese porcelain, West African coins, and artefacts from Thailand have been discovered in Qatar.[54] Archaeological remains from the 9th century suggest that Qatar's inhabitants used greater wealth to construct higher quality homes and public buildings. Over 100 stone-built houses, two mosques, and an Abbasid fort were constructed in Murwab during this period.[58][59] When the caliphate's prosperity declined in Iraq, so too did it in Qatar.[60] Qatar is mentioned in 13th-century Muslim scholar Yaqut al-Hamawi's book, Mu'jam Al-Buldan, which alludes to the Qataris' fine striped woven cloaks and their skills in improvement and finishing of spears.[61]

Much of eastern Arabia was controlled by the Usfurids in 1253, but control of the region was seized by the prince of Ormus in 1320.[62] Qatar's pearls provided the kingdom with one of its main sources of income.[63] In 1515, Manuel I of Portugal vassalised the Kingdom of Ormus. Portugal went on to seize a significant portion of eastern Arabia in 1521.[63][64] In 1550, the inhabitants of Al-Hasa voluntarily submitted to the rule of the Ottomans, preferring them to the Portuguese.[65]

Portuguese era

After the fall of the Jabrid Dynasty with the conquest of Bahrain by the Portuguese, the Arabian coast up to Al Hassa came under the rule and influence of the Portuguese empire. Attempts by the Ottomans to dominate the region were eliminated with the reconquest of the castle of Tarout[66] or Al Qatif in 1551.

Archaeological finds are still being excavated from one of the Portuguese fortresses that served as a base to dominate the region as Ruwayda.[67] The first representation of Qatar appears on the Portuguese map by Luis Lázaro in 1563, showing the "city of Qatar" as a fortress.[68] Having retained a negligible military presence in the area, the Ottomans were expelled by the Bani Khalid tribe and their emirate in 1670.[69]

Bahraini and Saudi rule (1783–1868)

In 1766, members of the Al Khalifa family of the Utub tribal confederation migrated from Kuwait to Zubarah in Qatar.[70][71] By the time of their arrival, the Bani Khalid exercised weak authority over the peninsula, notwithstanding the fact that the largest village was ruled by their distant kin.[72] In 1783, Qatar-based Bani Utbah clans and allied Arab tribes invaded and annexed Bahrain from the Persians. The Al Khalifa imposed their authority over Bahrain and retained their jurisdiction over Zubarah.[70]

Following his swearing-in as crown prince of the Wahhabi in 1788, Saud ibn Abd al-Aziz moved to expand Wahhabi territory eastward towards the Persian Gulf and Qatar. After defeating the Bani Khalid in 1795, the Wahhabi were attacked on two fronts. The Ottomans and Egyptians assaulted the western front, while the Al Khalifa in Bahrain and the Omanis launched an attack against the eastern front.[73][74] Upon being made aware of the Egyptian advance on the western frontier in 1811, the Wahhabi amir reduced his garrisons in Bahrain and Zubarah in order to redeploy his troops. Said bin Sultan, ruler of Muscat, capitalised on this opportunity and raided the Wahhabi garrisons on the eastern coast, setting fire to the fort in Zubarah. The Al Khalifa was effectively returned to power thereafter.[74]

As punishment for piracy, an East India Company vessel bombarded Doha in 1821, destroying the town and forcing hundreds of residents to flee. In 1825, the House of Thani was established with Sheikh Mohammed bin Thani as the first leader.[75]

Although Qatar was considered a dependency of Bahrain, the Al Khalifa faced opposition from the local tribes. In 1867, the Al Khalifa, along with the ruler of Abu Dhabi, sent a massive naval force to Al Wakrah in an effort to crush the Qatari rebels. This resulted in the maritime Qatari–Bahraini War of 1867–68, in which Bahraini and Abu Dhabi forces sacked and looted Doha and Al Wakrah.[76] The Bahraini hostilities were in violation of the Perpetual Truce of Peace and Friendship of 1861. The joint incursion, in addition to the Qatari counter-attack, prompted British Political Resident, Colonel Lewis Pelly to impose a settlement in 1868. His mission to Bahrain and Qatar and the resulting peace treaty were milestones because they implicitly recognised the distinctness of Qatar from Bahrain and explicitly acknowledged the position of Mohammed bin Thani. In addition to censuring Bahrain for its breach of agreement, Pelly negotiated with Qatari sheikhs who were represented by Mohammed bin Thani.[77] The negotiations were the first stage in the development of Qatar as a sheikhdom.[78]

Ottoman period (1871–1915)

Under military and political pressure from the governor of the Ottoman Vilayet of Baghdad, Midhat Pasha, the ruling Al Thani tribe submitted to Ottoman rule in 1871.[79] The Ottoman government imposed reformist (Tanzimat) measures concerning taxation and land registration to fully integrate these areas into the empire.[79] Despite the disapproval of local tribes, Al Thani continued supporting the Ottoman rule. Qatari-Ottoman relations stagnated, and in 1882 they suffered further setbacks when the Ottomans refused to aid Al Thani in his expedition of Abu Dhabi-occupied Khor Al Adaid and offered only limited support in the Qatari–Abu Dhabi War, mainly due to fear of British intervention on Abu Dhabi's side.[80] In addition, the Ottomans supported the Ottoman subject Mohammed bin Abdul Wahab who attempted to supplant Al Thani as kaymakam of Qatar in 1888.[81] This eventually led Al Thani to rebel against the Ottomans, whom he believed were seeking to usurp control of the peninsula. He resigned as kaymakam and stopped paying taxes in August 1892.[82]

In February 1893, Mehmed Hafiz Pasha arrived in Qatar in the interests of seeking unpaid taxes and accosting Jassim bin Mohammed's opposition to proposed Ottoman administrative reforms. Fearing that he would face death or imprisonment, Jassim retreated to Al Wajbah (16 km or 10 mi west of Doha), accompanied by several tribe members. Mehmed's demand that Jassim disband his troops and pledge his loyalty to the Ottomans was met with refusal. In March, Mehmed imprisoned Jassim's brother and 13 prominent Qatari tribal leaders on the Ottoman corvette Merrikh as punishment for his insubordination. After Mehmed declined an offer to release the captives for a fee of 10,000 liras, he ordered a column of approximately 200 troops to advance towards Jassim's Al Wajbah Fort under the command of Yusuf Effendi, thus signalling the start of the Battle of Al Wajbah.[54]

Effendi's troops came under heavy gunfire by a sizable troop of Qatari infantry and cavalry shortly after arriving at Al Wajbah. They retreated to Shebaka fortress where they were again forced to draw back from a Qatari incursion. After they withdrew to Al Bidda fortress, Jassim's advancing column besieged the fortress, resulting in the Ottomans' concession of defeat and agreement to relinquish their captives in return for the safe passage of Mehmed Pasha's cavalry to Hofuf by land.[83] Although Qatar did not gain full independence from the Ottoman Empire, the result of the battle forced a treaty that would later form the basis of Qatar's emerging as an autonomous country within the empire.[84]

British period (1916–1971)

By the Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913, the Ottomans agreed to renounce their claim to Qatar and withdraw their garrison from Doha. However, with the outbreak of World War I, nothing was done to carry this out, and the garrison remained in the fort at Doha, although its numbers dwindled as men deserted. In 1915, with the presence of British gunboats in the harbour, Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani (who was pro-British) persuaded the remainder to abandon the fort, and when British troops approached the following morning they found it deserted.[85][86]

Qatar became a British protectorate on 3 November 1916[87] when the United Kingdom signed a treaty with Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani to bring Qatar under its Trucial System of Administration. The treaty reserved foreign affairs and defence to the United Kingdom but allowed internal autonomy. While Abdullah agreed not to enter into any relations with any other power without the prior consent of the British government, the latter guaranteed the protection of Qatar from aggression by sea and provide its 'good offices' in the event of an attack by land. This latter undertaking was left deliberately vague.[85][88]

On 5 May 1935, while agreeing an oil concession with the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, Abdullah signed another treaty with the British government which granted Qatar protection against internal and external threats.[85] Oil reserves were first discovered in 1939. Exploitation and development were, however, delayed by World War II.[89]

The focus of British interests in Qatar changed after the Second World War with the independence of India, the creation of Pakistan in 1947, and the development of oil in Qatar. In 1949, the appointment of the first British political officer in Doha, John Wilton, signified a strengthening of Anglo-Qatari relations.[90] Oil exports began in 1949, and oil revenues became the country's main source of revenue; the pearl trade had gone into decline. These revenues were used to fund the expansion and modernisation of Qatar's infrastructure.

When Britain officially announced in 1968 that it would withdraw from the Persian Gulf in three years' time, Qatar joined talks with Bahrain and seven other Trucial States to create a federation. Regional disputes, however, persuaded Qatar and Bahrain to withdraw from the talks and become independent states separate from the Trucial States, which went on to become the United Arab Emirates.

Independence and later (1971–2000)

Under an agreement with the United Kingdom,[91][92] on 3 September 1971, the "special treaty arrangements" that were "inconsistent with full international responsibility as a sovereign and independent state" were terminated.[92]

In 1991, Qatar played a significant role in the Gulf War, particularly during the Battle of Khafji in which Qatari tanks rolled through the streets of the town and provided fire support for Saudi Arabian National Guard units that were engaging Iraqi Army troops. Qatar allowed coalition troops from Canada to use the country as an airbase to launch aircraft on combat air patrol duty and also permitted air forces from the United States and France to operate in its territories.[40]

In 1995, Emir Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani seized control of the country from his father Khalifa bin Hamad Al Thani, with the support of the armed forces and cabinet, as well as neighbouring states[93] and France.[94] Under Emir Hamad, Qatar experienced a moderate degree of liberalisation, including the launch of the Al Jazeera television station (1996), the endorsement of women's suffrage or right to vote in municipal elections (1999), drafting its first written constitution (2005) and inauguration of a Roman Catholic church (2008).[citation needed]

21st century

Qatar's economy and status as a regional power rapidly grew in the 2000s. According to the UN, the nation's economic growth, measured by GDP, was the fastest in the world during this decade.[95][96] The basis of this growth lay in the exploitation of natural gas in the North Field during the 1990s. At the same time, the population tripled between 2001 and 2011, mostly from an influx of foreigners.[97]

In 2003, Qatar served as the United States Central Command headquarters and one of the main launching sites of the invasion of Iraq.[98] In March 2005, a suicide bombing killed a British teacher[99] at the Doha Players Theatre, shocking the country, which had not previously experienced acts of terrorism. The bombing was carried out by Omar Ahmed Abdullah Ali, an Egyptian resident in Qatar who had suspected ties to Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.[100][101] The increased influence of Qatar and its role during the Arab Spring, especially during the Bahraini uprising in 2011, worsened longstanding tensions with Saudi Arabia, the neighboring United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain.[citation needed]

In 2010, Qatar won the right to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup, making it the first country in the Middle East to be selected to host the tournament. The awarding increased further investment and developments within the nation during the 2010s.[102] In June 2013, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani became the emir of Qatar after his father handed over power.[103] Sheikh Tamim has prioritised improving the domestic welfare of citizens, which includes establishing advanced healthcare and education systems, and expanding the country's infrastructure in preparation for the hosting of the 2022 World Cup.[104] Qatar hosted the 2022 FIFA World Cup from 21 November to 18 December, becoming the first Arab and Muslim-majority country to do so, and the third Asian country to host it following the 2002 FIFA World Cup in Japan and South Korea.[105]

Politics

Qatar is officially a semi-constitutional monarchy,[106][107] but the wide powers retained by the monarchy have it bordering an absolute monarchy[108][109] ruled by the Al Thani family.[110][111] The Al Thani dynasty has been ruling Qatar since the family house was established in 1825.[3] In 2003, Qatar adopted a constitution that provided for the direct election of 30 of the 45 members of a legislature.[3][112][113] The constitution was overwhelmingly approved in a referendum, with almost 98% in favour.[114][115] Despite this, the government remains authoritarian.[116][6] According to the V-Dem Democracy indices Qatar is 2023 the second least electoral democratic country in the Middle East.[117] Qatari law does not permit the establishment of political bodies or trade unions.[118]

The eighth emir of Qatar is Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani.[119] The emir has the exclusive power to appoint the prime minister and cabinet ministers who, together, constitute the Council of Ministers, which is the supreme executive authority in the country.[120] The Council of Ministers also initiates legislation.[120]

The Consultative Assembly is made up of 30 popularly-elected members and 15 appointed by the emir. It can block legislation with a simple majority and can dismiss ministers, including the prime minister, with a two-thirds vote. The assembly had its first elections in October 2021 after several postponements.[121][122][123]

Law

According to Qatar's Constitution, Sharia law is the main source of Qatari legislation,[124][125] although in practice Qatar's legal system is a mixture of civil law and Sharia.[126][127] Sharia is applied to family law, inheritance, and several criminal acts (including adultery, robbery, and murder). In some cases, Sharia-based family courts treat a female's testimony as being worth half that of a man.[128] Codified family law was introduced in 2006. Islamic polygyny is permitted.[94]

Judicial corporal punishment is a punishment in Qatar. Only Muslims considered medically fit are liable to have such sentences carried out. Flogging is employed as a punishment for alcohol consumption or illicit sexual relations.[129] Article 88 of the criminal code declares that the penalty for adultery is 100 lashes.[130] Stoning is a legal punishment in Qatar,[131] and apostasy and homosexuality are crimes punishable by the death penalty; however, the penalty has not been carried out for either crime.[132][133] Blasphemy can result in up to seven years in prison, while proselytising can incur a 10-year sentence.[132][134]

Alcohol consumption is partially legal; some five-star luxury hotels are allowed to sell alcohol to non-Muslim customers.[135][136] Muslims are not allowed to consume alcohol, and those caught consuming it are liable to flogging or deportation. Non-Muslim expatriates can obtain a permit to purchase alcohol for personal consumption. The Qatar Distribution Company (a subsidiary of Qatar Airways) is permitted to import alcohol and pork; it operates the only liquor store in the country, which also sells pork to holders of liquor licences.[137][138] Qatari officials had indicated a willingness to allow alcohol in "fan zones" at the 2022 FIFA World Cup.[139] However, on 18 November, two days before the start of the games, Qatari officials announced alcoholic beverages would not be permitted within the stadiums.[140]

In 2014, a modesty campaign was launched to remind tourists of the country's restrictive dress code.[141] Female tourists were advised not to wear leggings, miniskirts, sleeveless dresses, or short or tight clothing in public. Men were warned against wearing shorts and singlets.[142]

Foreign relations

Qatar's international profile and active role in international affairs have led some analysts to identify it as a middle power. Since 2022, it has been a major non-NATO ally of the United States.[143] Qatar also has particularly strong ties with France,[144] China,[145] Iran,[146] Turkey,[147] as well as a number of Islamist movements in the Middle East such as the Muslim Brotherhood.[148][149][150] The country is an early member of OPEC and a founding member of the Gulf Cooperation Council, as well as a member of the Arab League.[3] Diplomatic missions to Qatar are based in its capital, Doha.

Regional relations and foreign policies are characterized by the strategy of balancing and alliance building among regional and great powers. It maintains independent foreign policy and engages in regional balancing to secure its strategic priorities and to have recognition on the regional and international level.[149][151][152] As a comparatively small state in the gulf, Qatar established an "open-door" foreign policy where Qatar maintains ties to all parties and regional players in the region.[153]

In 2011, Qatar joined NATO operations in Libya and reportedly armed Libyan opposition groups.[154] It was also a major funder of weapons for rebel groups in the Syrian civil war.[155] Qatar participated in the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen against the Houthis and forces loyal to former President Ali Abdullah Saleh.[156] Since the 2000s, Qatar increasingly emerged on a wider foreign policy stage especially as a mediator, such as for Middle Eastern conflicts;[157] for example, Qatar mediated between the rival Palestinian factions Fatah and Hamas in 2006[158] and helped unite Lebanese leaders into forming a political agreement during the 2008 crisis.[159] Qatar has also emerged as mediators in African and Asian affairs, notably holding a peace process for Sudan amid the Darfur conflict[160] and facilitating peace talks for Afghanistan, setting up a political "office" for the Afghan Taliban to facilitate talks. Ahmed Rashid, writing in the Financial Times, stated that through the office Qatar has "facilitated meetings between the Taliban and many countries and organisations, including the US state department, the UN, Japan, several European governments and non-governmental organisations, all of whom have been trying to push forward the idea of peace talks."[161] It played a major role in establishing the first ceasefire in the 2023 Israel-Hamas war and the concurrent initial hostage exchange. These high-risk diplomatic middle man endeavors (and its own rigorous defense stance) have thus earned it a reputation as "a prickly Switzerland".[162]

In June 2017, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, Egypt and Yemen broke diplomatic ties with Qatar, accusing Qatar of supporting terrorism.[163] The crisis escalated a dispute over Qatar's support of the Muslim Brotherhood, which is considered a terrorist organization by some Arab nations.[164] The diplomatic crisis ended in January 2021 with the signing of AlUla declaration.[165]

On 2 October 2020, Qatari authorities strip-searched 13 Australian women on a plane at Hamad International Airport over a premature baby found in a bathroom at the terminal. This caused an international incident with Australia.[166][167] In September 2023, Qatar mediated the US- Iran prisoners swap deal. Iran freed five Americans in exchange for five Iranians held in the US and transfer $6 billion in frozen Iranian money from South Korea to Qatar.[168] In October 2023 United States President Joe Biden thanked the Qatar's Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani for his help in mediating a landmark prisoner swap deal with Iran.[169]

Military

The Qatar Armed Forces consist of 12,000 personnel in the Qatari Emiri Land Forces, 2,500 in the Navy, 2,000 in the Air Force, and 5,000 in the Internal Security Forces.[170] In 2008 Qatar spent US$2.3 billion on its military, which was 2.3% of the GDP,[171] and its military spending increased to US$7.49 billion as of 2022.[170] After the Arab spring events in 2011 and a diplomatic incident with Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries in 2014, Qatar started expanding its armed forces.[172] The country introduced conscription in 2013, the first Gulf state to do so in recent years. It is mandatory for Qatari male citizens to serve for up to 4 months, though not all of them are called up. The national service term was extended to one year in 2018. About 2,000 conscripts pass through the Qatar Armed Forces annually. Military service has become more popular in Qatar due to the recent tensions with Saudi Arabia and the UAE.[173][174] Since 2017, Qatar has also purchased large quantities of equipment from European countries and the United States, making its air force one of the largest among the Gulf states.[170][172]

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) found that in 2010–2014 Qatar was the 46th-largest arms importer in the world. SIPRI writes that Qatar's plans to transform and significantly enlarge its armed forces have accelerated.[175] In 2015, Qatar was the 16th largest arms importer in the world, and in 2016, it was the 11th largest, according to SIPRI.[176]

Qatar has signed defense pacts with the United States, the United Kingdom, and France.[177] The forward headquarters of United States Central Command, Al Udeid Air Base, is located in Qatar and houses about 10,000 American military personnel.[172]

During the 2011 military intervention in Libya, Qatar deployed six Mirage 2000 fighter jets to assist the NATO air campaign against the Libyan government and special forces to provide training to Libyan rebels.[178] Since the start of Saudi-led intervention in the Yemeni civil war, by September 2015 Qatar sent 1,000 troops, 200 armored vehicles, and 30 Apache helicopters to assist Saudi Arabia with its military operations in Yemen.[179][180] In June 2017, at the start of the diplomatic crisis with Saudi Arabia, Qatar withdrew its forces from Yemen.[181]

Human rights

Qatar's human rights record has been regarded by academics and non-governmental organisations as being generally poor, with restrictions on civil liberties such as the freedoms of association, expression and the press, as well as its treatment of thousands of migrant workers amounting to forced labour for projects in the country.[182][183]

In May 2012, Qatari officials declared their intention to allow the establishment of an independent trade union.[184] In 2014, Qatar commissioned international law firm DLA Piper to produce a report investigating the immigrant labour system. In May 2014, DLA Piper released more than 60 recommendations for reforming the kafala system including the abolition of exit visas and the introduction of a minimum wage, which Qatar has pledged to implement. Qatar also announced it would scrap its sponsor system for foreign labour, which requires that all foreign workers be sponsored by local employers.[185]

The UN Committee Against Torture found that the provisions for flogging and stoning within the Qatari criminal code constituted a breach of the obligations imposed by the UN Convention Against Torture.[186][187] Homosexual acts are illegal and can be punished by death.[188] However, there is no such evidence that the death penalty has been given for same-sex relations due to homosexual acts.[189]

Under the provisions of Qatar's sponsorship law, sponsors had the unilateral power to cancel workers' residency permits, deny workers' ability to change employers, report a worker as "absconded" to police authorities, and deny permission to leave the country.[190] As a result, sponsors may restrict workers' movements, and workers may be afraid to report abuses or claim their rights.[190] According to the ITUC, the visa sponsorship system allows the exaction of forced labour by making it difficult for a migrant worker to leave an abusive employer or travel overseas without permission.[191] Qatar also did not maintain wage standards for its immigrant labourers. Additional changes to labour laws include a provision guaranteeing that all workers' salaries are paid directly into their bank accounts and new restrictions on working outdoors in the hottest hours during the summer.[192]

In 2016 laws were reformed to mandate that companies that fail to pay workers' wages on time could temporarily lose their ability to hire more employees.[193][194] Human Rights Watch claimed that the changes might fail to address some labour rights issues.[195][196] A minimum wage was instituted in 2021.[197] The country enfranchised women at the same time as men in connection with the 1999 elections for a Central Municipal Council.[112][198] These elections—the first-ever in Qatar—were intentionally held on 8 March 1999, International Women's Day.[112]

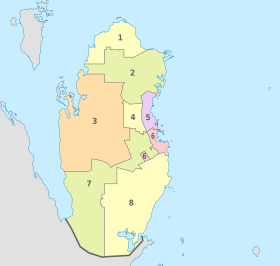

Administrative divisions

Qatar is divided into eight municipalities (Arabic: baladiyah).[199]

For statistical purposes, the municipalities are further subdivided into 98 zones,[200] which are in turn subdivided into blocks.[201]

Former municipalities

- Al Jemailiya (until 2004)[202]

- Al Ghuwariyah (until 2004)[202]

- Jariyan al Batnah (until 2004)[202]

- Mesaieed (Umm Sa'id) (until 2006)[203]

Geography

The Qatari peninsula protrudes 160 kilometres (100 mi) into the Persian Gulf, north of Saudi Arabia. It lies between latitudes 24° and 27° N, and longitudes 50° and 52° E. Most of the country consists of a low, barren plain, covered with sand. To the southeast lies the Khor al Adaid ("Inland Sea"), an area of rolling sand dunes surrounding an inlet of the Persian Gulf.

The highest point is Qurayn Abu al Bawl at 103 metres (338 ft)[3] in the Jebel Dukhan to the west, a range of low limestone outcroppings running north–south from Zikrit through Umm Bab to the southern border. The Jebel Dukhan area also contains Qatar's main onshore oil deposits, while the natural gas fields lie offshore, to the northwest of the peninsula.[citation needed]

Biodiversity

Qatar became part of the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity in 1996.[204] It subsequently produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan in 2005.[205] A total of 142 fungal species have been recorded from Qatar.[206] A book recently produced by the Ministry of Environment documents the lizards known or believed to occur in Qatar, based on surveys conducted by an international team of scientists and other collaborators.[207]

According to the Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research, carbon dioxide emissions per person average over 30 tonnes, one of the highest in the world.[208]

Climate

| Climate data for Qatar | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 22 (72) |

23 (73) |

27 (81) |

33 (91) |

39 (102) |

42 (108) |

42 (108) |

42 (108) |

39 (102) |

35 (95) |

30 (86) |

25 (77) |

33 (92) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 14 (57) |

15 (59) |

17 (63) |

21 (70) |

27 (81) |

29 (84) |

31 (88) |

31 (88) |

29 (84) |

25 (77) |

21 (70) |

16 (61) |

23 (74) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 12.7 (0.50) |

17.8 (0.70) |

15.2 (0.60) |

7.6 (0.30) |

2.5 (0.10) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2.5 (0.10) |

12.7 (0.50) |

71 (2.8) |

| Source: "Doha Annual Weather Averages". World Weather Online. Retrieved 24 December 2022. | |||||||||||||

| Sea Climate Data For Doha | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 21.0 (69.8) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.3 (73.9) |

27.8 (82) |

30.5 (86.9) |

32.4 (90.3) |

33.6 (92.5) |

32.8 (91) |

30.8 (87.4) |

27.5 (81.5) |

23.5 (74.3) |

26.9 (80.5) |

| Source:[209] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Before the discovery of oil, the economy focused on fishing and pearl hunting. A report prepared by local governors of the Ottoman Empire in 1892 states that income from pearl hunting in 1892 is 2,450,000 kran.[76] After the introduction of the Japanese cultured pearl onto the world market in the 1920s and 1930s, Qatar's pearling industry crashed. Oil was discovered in Qatar in 1940, in Dukhan Field.[210] The discovery transformed the state's economy. Now, the country has a high standard of living for its legal citizens. With no income tax, Qatar (along with Bahrain) is one of the countries with the lowest tax rates in the world. The unemployment rate in June 2013 was 0.1%.[211] Corporate law mandates that Qatari nationals must hold 51% of any venture in the emirate.[94] Trade and industry is overseen by the Ministry of Business and Trade.[212]

As of 2016[update], Qatar has the fourth highest GDP per capita in the world, according to the International Monetary Fund.[213] It relies heavily on foreign labor to grow its economy, to the extent that migrant workers compose 86% of the population and 94% of the workforce.[214][215] Economic growth has been almost exclusively based on its petroleum and natural gas industries, which began in 1940.[216] Qatar is the leading exporter of liquefied natural gas.[217] In 2012, it was estimated that Qatar would invest over $120 billion in the energy sector in the next 10 years.[218] The country was a member state of Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), having joined in 1961, and having left in January 2019.[219]

In 2012, Qatar retained its title of richest country in the world (according to per capita income) for the third time in a row, having first overtaken Luxembourg in 2010. According to the study published by the Washington-based Institute of International Finance, the per capita GDP at purchasing power parity (PPP) was $106,000 (QR387,000) in 2012, helping the country retain its ranking as the world's wealthiest nation. Luxembourg came a distant second with nearly $80,000 and Singapore third with per capita income of about $61,000.The research put Qatar's GDP at $182bn in 2012 and said it had climbed to an all-time high due to soaring gas exports and high oil prices. Its population stood at 1.8 million in 2012.

Established in 2005, Qatar Investment Authority is the country's sovereign wealth fund, specializing in foreign investment.[220] In 2012, with assets of $115bn, QIA was ranked 12th among the richest sovereign wealth funds in the world.[221] With billions of dollars in surpluses from the oil and gas industry, the Qatari government has directed investments into United States, Europe, and Asia Pacific. Qatar Holding is the international investment arm of QIA. Since 2009, Qatar Holding has received $30–40bn per year from the state. As of 2014[update], it has investments around the world in Valentino, Siemens, Printemps, Harrods, The Shard, Barclays Bank, Heathrow Airport, Paris Saint-Germain F.C., Volkswagen Group, Royal Dutch Shell, Bank of America, Tiffany, Agricultural Bank of China, Sainsbury's, BlackBerry,[222] and Santander Brasil.[223][224]

The country has no taxes on non-companies,[225] but authorities have announced plans to levy taxes on junk food and luxury items. The taxes would be implemented on goods that harm the human body—for example, fast food, tobacco products, and soft drinks. The rollout of these initial taxes is believed to be the result of the fall in oil prices and a deficit that the country faced in 2016. Additionally, the country saw job cuts in 2016 from its petroleum companies and other sectors in the government.[226][227]

Energy

As of 2012[update], Qatar has proven oil reserves of 15 billion barrels and gas fields that account for more than 13% of the global resource. The economy was in a downturn from 1982 to 1989. OPEC quotas on crude oil production, the lower price for oil, and the generally unpromising outlook on international markets reduced oil earnings. In turn, the Qatari government's spending plans had to be cut to match lower income. The resulting recessionary local business climate caused many firms to lay off expatriate staff. With the economy recovering in the 1990s, expatriate populations, particularly from Egypt and South Asia, have grown again.[citation needed]

Qatar's proven reserves of gas are the third-largest in the world, exceeding 250 trillion cubic feet (7,000 km3). The economy was boosted in 1991 by completion of the $1.5-billion Phase I of North Field gas development. In 1996, the Qatargas project began exporting liquefied natural gas to Japan.

Qatar's heavy industrial projects, all based in Umm Said, include a refinery with a 50,000 barrels (8,000 m3) per day capacity, a fertiliser plant for urea and ammonia, a steel plant, and a petrochemical plant. All these industries use gas for fuel. Most are joint ventures between European and Japanese firms and the state-owned QatarEnergy. The US is the major equipment supplier for Qatar's oil and gas industry, and US companies are playing a major role in North Field gas development.[228]

In 2008 Qatar launched its National Vision 2030 which highlights environmental development as one of the four main goals for Qatar over the next two decades.[229] The National Vision pledges to develop sustainable alternatives to oil-based energy to preserve the local and global environment.[229] Qatar has made investment in renewable resources a major goal for the country over the next two decades. By 2030, Qatar has set the goal of attaining 20% of its energy from solar power.[230] The country is well-positioned to capitalize on photovoltaic systems, as it has a global horizontal irradiance value of approximately 2,140 kWh per square meter annually. Furthermore, the direct irradiance parameter is roughly 2,008 kWh per square meter annually, implying that it would be able to benefit from concentrated solar power as well.[231] Qatar Foundation has been active in helping the solar power goals. It established Qatar Solar, which, together with Qatar Development Bank and German company SolarWorld, embarked on a joint venture resulting in the creation of Qatar Solar Technologies (QSTec). In 2017, QSTec commissioned its polysillicon plant in Ras Laffan. This plant has a capacity of 1.1 MW of solar power.[230]

Qatar pursues a vigorous programme of "Qatarisation", under which all joint venture industries and government departments strive to move Qatari nationals into positions of greater authority. Growing numbers of foreign-educated Qataris, including many educated in the US, are returning home to assume key positions formerly occupied by expatriates. To control the influx of expatriate workers, Qatar has tightened the administration of its foreign manpower programmes over the past several years. Security is the principal basis for Qatar's strict entry and immigration rules and regulations.[228]

Tourism

Qatar is one of the fastest growing countries in the field of tourism. According to the World Tourism rankings, more than 2.3 million international tourists visited in 2017. Qatar has become one of the most open countries in the Middle East due to its recent visa facilitation improvements, including allowing nationals of 88 countries to enter visa-free and free-of charge.[232] Qatar was recently put in the top eight in market climate in the Middle East by the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Survey 2019 of the World Economic Forum.[233][234] Doha is one of the fastest-growing hotel and hospitality markets in the world. The $220 billion spent on infrastructure since the successful World Cup bid of 2010 has helped boost the industry. Hotels have also been helped by the country’s geographic location. The tourism sector continues to witness a strong recovery with more than 729,000 international visitors in the first half of 2022, marking a 19% increase compared to the full year of 2021, and the aim is to raise tourism to 12% of GDP by 2030.[235][236]

The nation is also on course to experience a major jump in athletic and corporate tourism with hosting world-class tournaments such as the 2030 Asian Games and the 2022 FIFA World Cup.[237] Qatar National Airlines, as well as Hamad International Airport, provide travelers with one of the best transportation services in the world, and this has increased tourism in Qatar. Gulf News, a research center in Qatar, by examining the statistics of recent years and upcoming events, has predicted that this country will earn 11 billion and 900 million dollars from attracting foreign travelers by 2020, This is achieved with the reason for this upward trend is the increase in hospitality and attention to the country's culture in Qatar.[238]

Transport

In 2008 the public works authority (Ashghal), one of the bodies that oversees infrastructure development, underwent a major reorganisation in order to streamline and modernise the authority in preparation for major project expansions across all segments in the near future. Ashghal works in tandem with the Urban Planning and Development Authority, the body that designed the transportation master plan, instituted in March 2006 and running to 2025.[citation needed]

The road network is a major focus of the plan. Project highlights in this segment include the multibillion-dollar Doha Expressway and the Qatar Bahrain Causeway. Mass-transit options, such as a Doha metro, light-rail system and more extensive bus networks are also under development to ease road congestion. In addition, the railway system is being significantly expanded and could eventually form an integral part of a GCC-wide network linking all the Arab states of the Persian Gulf.

Hamad International Airport is located in Doha. In 2014, it replaced the former Doha International Airport as Qatar's principal airport. In 2016, the airport was named the 50th busiest airport in the world by passenger traffic, serving 37,283,987 passengers, a 20.2% increase from 2015.[citation needed] Qatar Airways is one of the largest airlines in the world that serves in six continents connecting more than 160 destinations every day. It has won Airline of the Year in 2011, 2012, 2015, 2017 and 2019 and employs more than 46,000 people.[239][240]

Qatar is increasingly activating its logistics and ports in order to participate in trade between Europe and China or Africa.[citation needed] For this purpose, ports such as Hamad Port are rapidly expanded and investments are made in their technology.[citation needed] The country is historically and currently part of the Maritime Silk Road that runs from the Chinese coast to the south via the southern tip of India to Mombasa, from there through the Red Sea via the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean, there to the Upper Adriatic region to the northern Italian hub of Trieste with its rail connections to Central Europe, Eastern Europe and the North Sea.[241][242][243] Hamad Port is Qatar's main seaport, located south of Doha in the Umm Al Houl area. Construction of the port began in 2010; it became operational in December 2016.[244] Capable of handling up to 7.8 million tonnes of products annually, the bulk of trade which passes through the port consists of food and building materials.[245] On the northern coast, Ras Laffan Port serves as the most extensive liquid natural gas export facility in the world.[246]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 25,000 | — |

| 1960 | 47,000 | +88.0% |

| 1970 | 110,000 | +134.0% |

| 1980 | 224,000 | +103.6% |

| 1990 | 476,000 | +112.5% |

| 2000 | 592,000 | +24.4% |

| 2010 | 1,856,000 | +213.5% |

| 2019 | 2,832,000 | +52.6% |

| source:[247][248] | ||

The number of people in Qatar fluctuates considerably depending on the season, since the country relies heavily on migrant labour. In early 2017, the population was 2.6 million, with foreigners making up a vast majority. Only 313,000 (12%) were Qatari citizens, while the remaining 2.3 million were expatriates.[20]

The combined number of South Asians (from the countries of the Indian subcontinent including Sri Lanka) represent over 1.5 million people (60%). Among these, Indians are the largest community, numbering 650,000 in 2017,[20] followed by 350,000 Nepalese, 280,000 Bangladeshis, 145,000 Sri Lankans, and 125,000 Pakistanis. The contingent of expatriates which are not of South Asian origin represent around 28% of Qatar's population, of which the largest group is 260,000 Filipinos and 200,000 Egyptians, plus many other nationalities (including nationals of other Arab countries, Europeans, etc.).[20]

Qatar's first demographic records date back to 1892, conducted by Ottoman governors in the region. Based on this census, which includes only the residents in cities, the population in 1892 was 9,830.[76] At the time of the first census, held in 1970, the population was 111,133.[249] The 2010 census recorded the population at 1,699,435.[8] In January 2013, the Qatar Statistics Authority estimated the population at 1,903,447, of which 1,405,164 were males and 498,283 females.[250] The influx of male labourers has skewed the gender balance, and women are now just one-quarter of the population.

Religion

Islam is the predominant religion and is the state religion although not the only religion practiced in the country,[251] and the constitution guarantees freedom to practise any faith within "moral" bounds.[252] Most citizens belong to the Salafi Muslim movement of Wahhabism,[253][254][255] and 5–15% of Muslims follow Shia Islam with other Islamic sects being very small in number.[256] In 2010, Qatar's population was 67.7% Muslim, 13.8% Christian, 13.8% Hindu, and 3.1% Buddhist; other religions and religiously unaffiliated people accounted for the remaining 1.6%.[257]

Sharia is the main source of legislation according to the constitution.[124][125] Qatar's interpretation of Sharia is said to be not as "strict" as neighboring Saudi Arabia[258] but not as "liberal" as Dubai.[259] The vision of the Ministry of Awqaf and Islamic Affairs is "to build a contemporary Islamic society along with fostering the Sharee’ah and cultural heritage".[260]

The non-Muslim population is composed almost entirely of foreign migrants. Since 2008, Christians have been allowed to build churches on ground donated by the government,[261][262] Active churches include the Mar Thoma Church, Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, the Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady of the Rosary and the Anglican Church of the Epiphany.[263][264][265] There are also two Mormon wards[263][264][265] and a Bahá'í community.[266]

Languages

Arabic is the official language, with Qatari Arabic the local dialect. Qatari Sign Language is the language of the deaf community. English is commonly used as a second language,[267] and a rising lingua franca, especially in commerce, to the extent that steps are being taken to try to preserve Arabic from English's encroachment.[268] English is particularly useful for communication with Qatar's large expatriate community. In the medical community, and in situations such as the training of nurses to work in Qatar, English acts as a lingua franca.[269] Reflecting the multicultural make-up of the country, many other languages are also spoken, including Persian, Baluchi, Brahui, Hindi, Malayalam, Urdu, Pashto, Kannada, Tamil, Telugu, Nepali, Sinhalese, Bengali, Tagalog, Tulu and Indonesian.[270]

Healthcare

Healthcare standards are generally high. Qatari citizens are covered by a national health-insurance plan, while expatriates must either receive health insurance from their employers, or in the case of the self-employed, purchase insurance.[271] Government healthcare spending is among the highest in the Middle East, with $4.7 billion being invested in healthcare in 2014.[272] This was a $2.1 billion increase from 2010.[273] The premier healthcare provider is Hamad Medical Corporation, established by the government as a non-profit healthcare provider, which runs a network of hospitals, ambulance services, and a home healthcare service, all of which are accredited by the Joint Commission.[citation needed]

In 2010, spending on healthcare accounted for 2.2% of the country's GDP; the highest in the Middle East.[274] In 2006, there were 23.12 physicians and 61.81 nurses per 10,000 inhabitants.[275] The life expectancy at birth was 82.08 years in 2014, or 83.27 years for males and 77.95 years for females, rendering it the highest life expectancy in the Middle East.[276] Qatar has a low infant mortality rate of 7 in 100,000.[277]

In 2006, there were 25 beds per 10,000 people, and 27.6 doctors and 73.8 nurses per 10,000 people.[278] In 2011, the number of beds decreased to 12 per 10,000 people, whereas the number of doctors increased to 28 per 10,000 people. While the country has one of the lowest proportions of hospital beds in the region, the availability of physicians is the highest in the GCC.[279]

Culture

The culture of Qatar is similar to other countries in Eastern Arabia, being significantly influenced by Islam. Qatar National Day, hosted annually on 18 December, has had an important role in developing a sense of national identity.[280] It is observed in remembrance of Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani's succession to the throne and his subsequent unification of the country's various tribes.[281][282]

The Doha Cultural Festival is one of the cultural activities carried out annually by the Qatari Ministry of Culture, Arts and Heritage, which began in 2002 with the aim of spreading Qatari culture inside and outside Qatar.[citation needed]

Arts

Qatari officials, especially the Al Thani family and the sister of the Emir of Qatar, Al-Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, pay special attention to art.[283][284] Al-Mayassa leads the Qatar Museums Authority. The Museum of Islamic Art, opened in 2008, is regarded as one of the best museums in the region.[285] This and several other Qatari museums, like the Arab Museum of Modern Art, fall under the Qatar Museums Authority,[286] which also sponsors artistic events abroad, such as major exhibitions by Takahashi Murakami in Versailles (2010) and Damien Hirst in London (2012).

Qatar is the world's biggest buyer in the art market by value.[287] The Qatari cultural sector is being developed to enable the country to reach world recognition to contribute to the development of a country that comes mainly from its resources from the gas industry.[288]

Literature

Qatari literature traces its origins back to the 19th century. Originally, written poetry was the most common form of expression. Abdul Jalil Al-Tabatabai and Mohammed bin Abdullah bin Uthaymeen, two poets dating back to the early 19th century, formed the corpus of Qatar's earliest written poetry. Poetry later fell out of favor after Qatar began reaping the profits from oil exports in the mid-20th century and many Qataris abandoned their Bedouin traditions in favor of more urban lifestyles.[289]

Due to the increasing number of Qataris who began receiving formal education during the 1950s and other significant societal changes, 1970 witnessed the introduction of the first short story anthology, and in 1993 the first locally authored novels were published. Poetry, particularly the predominant nabati form, retained some importance but would soon be overshadowed by other literary types.[289] Unlike most other forms of art in Qatari society, females have been involved in the modern literature movement on a similar magnitude to males.[290]

Media

Qatar's media was classified as "not free" in the 2014 Freedom of the Press report by Freedom House.[291] TV broadcasting was started in 1970.[292] Al Jazeera is a main television network headquartered in Doha. Al Jazeera initially launched in 1996 as an Arabic news and current affairs satellite TV channel of the same name and has since expanded into a global network of several speciality TV channels.

It has been reported that journalists practice self-censorship, particularly in regards to the government and ruling family of Qatar.[293] Criticism of the government, emir, and ruling family in the media is illegal. According to article 46 of the press law "The Emir of the state of Qatar shall not be criticised and no statement can be attributed to him unless under a written permission from the manager of his office."[294] Journalists are also subject to prosecution for insulting Islam.[291]

In 2014, a Cybercrime Prevention Law was passed. The law is said to restrict press freedom and carries prison sentences and fines for broad reasons such as jeopardising local peace or publishing false news.[295] The Gulf Center for Human Rights has stated that the law is a threat to freedom of speech and has called for certain articles of the law to be revoked.[296]

Press media has undergone expansion in recent years. There are currently seven newspapers in circulation in Qatar, with four being published in Arabic and three being published in English.[297] There are also newspapers from India, Nepal and Sri Lanka with editions printed from Qatar.[citation needed]

In regards to telecommunication infrastructure, Qatar is the highest-ranked Middle Eastern country in the World Economic Forum's Network Readiness Index (NRI)—an indicator for determining the development level of a country's information and communication technologies. Qatar ranked number 23 overall in the 2014 NRI ranking, unchanged from 2013.[298]

Music

The music of Qatar is based on Bedouin poetry, song and dance. Traditional dances in Doha are performed on Friday afternoons; one such dance is the Ardah, a stylised martial dance performed by two rows of dancers who are accompanied by an array of percussion instruments, including al-ras (a large drum whose leather is heated by an open fire), tambourines and cymbals with small drums.[299] Other percussion instruments used in folk music include galahs (a tall clay jar) and tin drinking cups known as tus or tasat, usually used in conjunction with a tabl, a longitudinal drum beaten with a stick.[300] String instruments, such as the oud and rebaba, are also commonly used.[299]

Sport

Association football is the most popular sport in Qatar, both in terms of players and spectators.[301] Shortly after the Qatar Football Association became affiliated with FIFA in 1970, one of the country's earliest international accolades came in 1981 when the Qatar national under-20 team's emerged as runners-up to West Germany in that year's edition of the FIFA World Youth Championship after being defeated 4–0 in the final. At the senior level, Qatar has played host to three editions of the AFC Asian Cup; the first being the ninth edition in 1988, the second being the fifteenth edition held in 2011, and the third being the eighteenth edition held in 2023.[302] For the first time in the country's history, the Qatar national football team won the AFC Asian Cup in the 2019 edition hosted in the United Arab Emirates, beating Japan 3–1 in the final. They won all seven of their matches, conceding only a single goal throughout the tournament.[303] As hosts and defending champions in the following 2023 edition, Qatar successfully retained their title, defeating Jordan in the final.[304]

On 2 December 2010, Qatar won their bid to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup, despite never previously qualifying for the FIFA World Cup Finals.[305] Local organisers built seven new stadiums and expanded one existing stadium for this event.[306][307] Qatar's winning bid for the 2022 World Cup was greeted enthusiastically in the Persian Gulf region as it was the first time a country in the Middle East had been selected to host the tournament. At the same time, the bid was embroiled in much controversy, including allegations of bribery and interference in the investigation of the alleged bribery. European football associations also objected to the 2022 World Cup being held in Qatar for a variety of reasons, from the impact of warm temperatures on players' fitness, to the disruption it might cause in European domestic league calendars should the event be rescheduled to take place during winter.[308][309] In May 2014, Qatari football official Mohammed bin Hammam was accused of making payments totalling £3 million to officials in return for their support for the Qatar bid.[310][311] A FIFA inquiry into the bidding process in November 2014 cleared Qatar of any wrongdoing.[312][313]

The Guardian, a British national daily newspaper, produced a short documentary named "Abuse and exploitation of migrant workers preparing emirate for 2022".[314] A 2014 investigation by The Guardian reported that migrant workers who had been constructing luxurious offices for the organisers of the 2022 World Cup had not been paid in over a year, and were now "working illegally from cockroach-infested lodgings."[315] For 2014, Nepalese migrants involved in constructing infrastructure for the 2022 World Cup died at a rate of one every two days.[316] The Qatar 2022 organising committee responded to various allegations by claiming that hosting the World Cup in Qatar would act as a "catalyst for change" in the region.[317] According to a February 2021 article in The Guardian, some 6,500 migrant construction workers had died.[318] However, the World Cup in Qatar was the most expensive in the competition's history and had many modern technologies, with many expressing their satisfaction with the country's handling of the tournament.[319][failed verification]

Qatar was estimated to host a football fanbase of 1.6 million for the 2022 FIFA World Cup. However, the construction work in country was expected to only take the available 37,000 hotel rooms to 70,000 by the end of 2021. In December 2019, the Qatari World Cup officials approached the organizers of the Glastonbury Festival in England and the Coachella Festival in the United States, to plan huge desert campsites for thousands of football fans. The World Cup campsites on the outskirts were reported to have licensed bars, restaurants, entertainment and washing facilities. Moreover, two cruise ships were also reserved as temporary floating accommodations for nearly 40,000 people during the tournament.[320]

Though football is the most popular sport, other team sports have experienced considerable success at senior level. In 2015, the national handball team emerged as runners-up to France in the World Men's Handball Championship as hosts, however the tournament was marred by numerous controversies regarding the host nation and its team.[321] Further, in 2014, Qatar won the world championship in men's 3x3 basketball.[322]

Cricket is popular amongst the South Asian diaspora in Qatar. Casual street cricket is the most popular format of the game, but the Qatar Cricket Association has been a member of the International Cricket Council (ICC) since 1999 and the men's and women's national teams both play regularly in ICC competitions. The primary cricket ground in Qatar is the West End Park International Cricket Stadium.[323]

Basketball is a developed sport amongst Asian people in Qatar. Qatar hosted the 2005 FIBA Asia Championship, 2013 FIBA Asia 3x3 Championship, 2014 FIBA Asia Under-18 Championship and 2022 FIBA Under-16 Asian Championship.[citation needed] Qatar will host the 2027 FIBA Basketball World Cup making this become the first Arab country to host the FIBA Basketball World Cup.[324]

Khalifa International Tennis and Squash Complex in Doha hosted the WTA Tour Championships in women's tennis between 2008 and 2010. Doha holds the WTA Premier tournament Qatar Ladies Open annually. Since 2002, Qatar has hosted the annual Tour of Qatar, a cycling race in six stages. Every February, riders are racing on the roads across Qatar's flat land for six days. Each stage covers a distance of more than 100 km, though the time trial usually is a shorter distance. Tour of Qatar is organised by the Qatar Cycling Federation for professional riders in the category of Elite Men.[325]

The Qatar Army Skydiving Team has several different skydiving disciplines placing among the top nations in the world. The Qatar National Parachute team performs annually during Qatar's National Day and at other large events, such as the 2015 World Handball Championship.[326] Doha four times was the host of the official FIVB Volleyball Men's Club World Championship and three times host FIVB Volleyball Women's Club World Championship. Doha also hosted the Asian Volleyball Championship once.[327]

Education

Qatar hired the RAND Corporation to reform its K–12 education system.[217] Through Qatar Foundation, the country has built Education City, a campus that hosts local branches of the Weill Cornell Medical College, Carnegie Mellon School of Computer Science, Georgetown University School of Foreign Service, Northwestern's Medill School of Journalism, Texas A&M's School of Engineering, Virginia Commonwealth University School of the Arts and other Western institutions.[217][328]

The illiteracy rate was 3.1% for males and 4.2% for females in 2012, the lowest in the Arab-speaking world and 86th in the world.[329] Citizens are required to attend government-provided education from kindergarten through high school.[330] Qatar University, founded in 1973, is the country's oldest and largest institution of higher education.[331][332]

In November 2002, Emir Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani created The Supreme Education Council.[333] The Council directs and controls education for all ages from the pre-school level through the university level, including the "Education for a New Era" initiative which was established to try to position Qatar as a leader in education reform.[334][335] According to the Webometrics Ranking of World Universities, the top-ranking universities in the country are Qatar University (1,881st worldwide), Texas A&M University at Qatar (3,905th) and Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar (6,855th).[336]

In 2009, Qatar established the Qatar Science & Technology Park in Education City to link those universities with industry. Education City is also home to a fully accredited international Baccalaureate school, Qatar Academy. In addition, two Canadian institutions, the College of the North Atlantic (headquarters in Newfoundland and Labrador) and the University of Calgary, have inaugurated campuses in Doha. Other for-profit universities have also established campuses in the city.[337]

In 2012, Qatar was ranked third from the bottom of the 65 OECD countries participating in the PISA test of mathematics, reading and skills for 15- and 16-year-olds, despite having the highest per capita income in the world.[338][339] Qatar was ranked 50th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023, up from 65th in 2019.[340][341][342]

As part of its national development strategy, Qatar has outlined a 10-year strategic plan to improve the level of education.[343] The government has launched educational outreach programs, such as Al-Bairaq. Al-Bairaq was launched in 2010 aims to provide high school students with an opportunity to experience a research environment in the Center for Advanced Materials in Qatar University. The program encompasses the STEM fields and languages.[344]

Launched in 2006 as part of an initiative of the Qatar Foundation, the Qatar National Research Fund was created with the intent of securing public funds for scientific research. The fund functions as a means to diversify its economy from a primarily oil and gas-based one to a knowledge-based economy.[345] The Qatar Science & Technology Park (QSTP) was established by Qatar Foundation in March 2009 as an attempt to assist the country's transition towards a knowledge economy.[346][347] With a seed capital of $800 million and initially hosting 21 organizations,[347] the QSTP became Qatar's first free-trade zone.[348]

See also

References

- ^ Formally /ˈkɑːtɑːr, kəˈtɑːr/; But the possible English pronunciations include: /ˈkʌtɑːr, ˈkætɑːr, ˈkɑːtɑːr, -ər, kəˈtɑːr, kæˈtɑːr, kɑːˈtɑːr/; respectively: KUT-ar, KAT-, KAHT-, -ər, kə-TAR, kat-AR, kah-TAR.[13]

- ^ [ˈqɑtˤɑr], local vernacular pronunciation: [ˈɡɪtˤɑr] [14][15][16][17]

- ^ (Arabic: دولة قطر, romanized: Dawlat Qaṭar

- ^ "The Constitution" (PDF). Government Communications Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Population of Qatar by nationality". Priya Dsouza. 19 August 2019. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Qatar". CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 8 February 2012. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ^ "Population By Religion, Gender And Municipality March 2020". Qatar Statistics Authority.

- ^ "The objections to Qatar hosting the World Cup reek of Eurocentrism". NBC News. Archived from the original on 22 November 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

In condemning Qatar, we should remember that the population of this authoritarian monarchy

- ^ a b "Political Stability: the Mysterious Case of Qatar". Middle East Political and Economic Institute. Archived from the original on 22 November 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

; the Qatari state remains fundamentally autocratic

- ^ "Population structure". Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. 31 January 2020. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Populations". Qsa.gov.qa. Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Qatar)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "GINI index". World Bank. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. p. 289. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "List of left- & right-driving countries – World Standards". Archived from the original on 29 December 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ "Qatar". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d., and "Qatar". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. n.d.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). "Qatar". Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ "Definition of Qatar | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ^ a b Johnstone, T. M. (2008). "Encyclopaedia of Islam". Ķaṭar. Brill Online. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2013.(subscription required)

- ^ Fromherz, Allen James (2011). Qatar: A Modern History (1st ed.). Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-1626162037.

- ^ "Qatar: Freedom in the World 2020 Country Report". Freedom House. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Population of Qatar by nationality – 2017 report". Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ "The Constitution". Archived from the original on 24 October 2004. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ "GNI per capita, Atlas method (current US$) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 20 November 2022. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ Nations, United (8 September 2022). "Human Development Report 2021-22". Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ "Indices & Data | Human Development Reports". United Nations Development Programme. 14 March 2013. Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ "2022 World LNG Report Press Release" (PDF). International Gas Union (IGU). 6 July 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Where in the world do people emit the most CO2?". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Cooper, Andrew F. "Middle Powers: Squeezed out or Adaptive?". Public Diplomacy Magazine. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Kamrava, Mehran. "Mediation and Qatari Foreign Policy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Dagher, Sam (17 October 2011). "Tiny Kingdom's Huge Role in Libya Draws Concern". Online.wsj.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Qatar: Rise of an Underdog". Politicsandpolicy.org. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ Black, Ian (26 October 2011). "Qatar admits sending hundreds of troops to support Libya rebels". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ Casey, Paula; Vine, Peter (1992). The heritage of Qatar. Immel Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 9780907151500.

- ^ a b "History of Qatar". Qatar Statistics Authority. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ "Maps". Qatar National Library. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ a b "About us". Katara. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ Hazlitt, William (1851). The Classical Gazetteer: A Dictionary of Ancient Geography, Sacred and Profane. Whittaker & co.

- ^ Rahman, Habibur (2010). The Emergence of Qatar: The Turbulent Years 1627–1916. London: Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 9780710312136.

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (21 November 2022). "The 2022 World Cup is being hosted in Qatar, which, as everyone knows, is pronounced..." The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 November 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Toth, Anthony. "Qatar: Historical Background." A Country Study: Qatar Archived 9 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine (Helen Chapin Metz, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (January 1993). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Khalifa, Haya; Rice, Michael (1986). Bahrain Through the Ages: The Archaeology. Routledge. pp. 79, 215. ISBN 978-0710301123.

- ^ a b "History of Qatar" (PDF). www.qatarembassy.or.th. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Qatar. London: Stacey International, 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ Rice, Michael (1994). Archaeology of the Persian Gulf. Routledge. pp. 206, 232–233. ISBN 978-0415032681.

- ^ Magee, Peter (2014). The Archaeology of Prehistoric Arabia. Cambridge Press. pp. 50, 178. ISBN 9780521862318.

- ^ Sterman, Baruch (2012). Rarest Blue: The Remarkable Story Of An Ancient Color Lost To History And Rediscovered. Lyons Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0762782222.

- ^ Cadène, Philippe (2013). Atlas of the Gulf States. BRILL. p. 10. ISBN 978-9004245600.

- ^ "History of Qatar" (PDF). www.qatarembassy.or.th. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Qatar. London: Stacey International, 2000. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ Gillman, Ian; Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim (1999). Christians in Asia Before 1500. University of Michigan Press. pp. 87, 121. ISBN 978-0472110407. Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ Commins, David (2012). The Gulf States: A Modern History. I. B. Tauris. p. 16. ISBN 978-1848852785.

- ^ Habibur Rahman, p. 33

- ^ "AUB academics awarded $850,000 grant for project on the Syriac writers of Qatar in the 7th century AD" (PDF). American University of Beirut. 31 May 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ Kozah, Mario; Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim; Al-Murikhi, Saif Shaheen (2014). The Syriac Writers of Qatar in the Seventh Century. Gorgias Press LLC. p. 24. ISBN 978-1463203559.

- ^ "Bahrain". maritimeheritage.org. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2015.[better source needed]

- ^ a b c Fromherz, Allen (13 April 2012). Qatar: A Modern History. Georgetown University Press. pp. 44, 60, 98. ISBN 978-1-58901-910-2.

- ^ a b Rahman, Habibur (2006). The Emergence Of Qatar. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 978-0710312136.

- ^ A political chronology of the Middle East. Routledge / Europa Publications. 2001. p. 192. ISBN 978-1857431155. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ Page, Kogan (2004). Middle East Review 2003–04: The Economic and Business Report. Kogan Page Ltd. p. 169. ISBN 978-0749440664. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ Qatar, 2012 (The Report: Qatar). Oxford Business Group. 2012. p. 233. ISBN 978-1907065682.

- ^ Casey, Paula; Vine, Peter (1992). The heritage of Qatar. Immel Publishing. pp. 184–185. ISBN 9780907151500.

- ^ Russell, Malcolm (2014). The Middle East and South Asia 2014. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 151. ISBN 978-1475812350.

- ^ "History". qatarembassy.net. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ Larsen, Curtis (1984). Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarchaeology of an Ancient Society (Prehistoric Archeology and Ecology series). University of Chicago Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0226469065. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ a b Althani, Mohamed (2013). Jassim the Leader: Founder of Qatar. Profile Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-1781250709. Archived from the original on 12 December 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ Gillespie, Carol Ann (2002). Bahrain (Modern World Nations). Chelsea House Publications. p. 31. ISBN 978-0791067796. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ Anscombe, Frederick (1997). The Ottoman Gulf: The Creation of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. Columbia University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0231108393. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 23 February 2015.