Effects of the Siege of Leningrad

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2008) |

The 872-day Siege of Leningrad, Russia, resulted from the failure of the German Army Group North to capture Leningrad in the Eastern Front during World War II. The siege lasted from September 8, 1941, to January 27, 1944, and was one of the longest and most destructive sieges in history, devastating the city of Leningrad.

Civilian casualties

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2008) |

As Soviet records during the war were incomplete, the ultimate number of casualties during the siege is disputed. The death toll of the siege varies anywhere from 600,000 to 2,000,000 deaths.[1] After the war, the Soviet government reported about 670,000 registered deaths from 1941 to January 1944, explained as resulting mostly from starvation, stress and exposure.[2]

Some independent studies suggest a much higher death toll of between 700,000 and 1.5 million, with most estimates putting civilian losses at around 1.1 to 1.3 million.[3][4] Many of these victims, estimated at being at least half a million, were buried in the Piskarevskoye Cemetery. Hundreds of thousands of civilians who were unregistered with the city authorities and lived in the city before the war, or had become refugees there, perished during the siege with no record at all. About half a million people, both military and civilians, from Latvia, Estonia, Pskov and Novgorod, fled from the advancing Nazis and came to Leningrad at the beginning of the war.[citation needed]

The flow of refugees to the city stopped with the beginning of the siege. During the siege, part of the civilian population was evacuated from Leningrad, although many died in the process. Unregistered people died in numerous air-raids and from starvation and cold while trying to escape from the city. Their bodies were never buried or counted under the severe circumstances of constant bombing and other attacks by the Nazi forces. The total number of human losses during the 29 months of the siege of Leningrad is estimated as 1.5 million, both civilian and military.[5] Only 700,000 people were left alive of a 3.5 million pre-war population. Among them were soldiers, workers, surviving children and women. Of the 700,000 survivors, about 300,000 were soldiers who came from other parts of the country to help in the besieged city. By the end of the siege, Leningrad had become an empty "ghost-city" with thousands of ruined and abandoned homes.[citation needed]

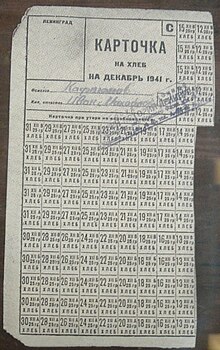

Food shortages

[edit]

Rations were reduced on September 2: manual workers had 600 grams of bread daily; state employees, 400 grams; and children and dependents (other civilians), 300 grams per day.

After heavy German bombing in August, September, and October 1941, all main food warehouses were destroyed and burned in massive fires. Huge amounts of stored food reserves, such as grain, flour and sugar, as well as other stored food, were completely destroyed. In one instance, melted sugar from the warehouses had flowed through the floors into the surrounding soil. Desperate citizens began digging up the frozen earth in an attempt to extract the sugar. This soil was on sale in the 'Haymarket' to housewives who tried to melt the earth to separate the sugar or to others who merely mixed this earth with flour.[6] The fires continued all over the city, due to the Germans bombing Leningrad non-stop for many months using various kinds of incendiary and high-explosive devices during 1941, 1942, and 1943.

In the first days of the siege, people finished all leftovers in "commercial" restaurants, which used up to 12% of all fats and up to 10% of all meat the city consumed. Soon all restaurants closed, and food rationing became the only way to save lives, rendering money obsolete. The carnage in the city from shelling and starvation (especially in the first winter) was appalling. At least nine of the staff at the seedbank set up by Nikolai I. Vavilov starved to death surrounded by edible seeds so that its more than 200,000 items would be available to future generations.[7]

It was calculated that the provisions both for army and civilians would last as follows (on September 12, 1941):

- Grain and flour (35 days)

- Groats and pasta (31 days)

- Meat and livestock (33 days)

- Fats (45 days)

- Sugar and confectionery (60 days)

On the same day, another reduction of food took place: the workers received 500 grams of bread; employees and children, 300 grams; and dependants, 250 grams. Rations of meat and groats were also reduced, but the issue of sugar, confectionery and fats was increased instead. The army and the Baltic Fleet had some emergency rations, but these were not sufficient, and were used up in weeks. The flotilla of Lake Ladoga was not well equipped for war, and was almost destroyed in bombing by the German Luftwaffe. Several barges with grain were sunk in Lake Ladoga in September 1941 alone, later recovered from the water by divers.

This grain was delivered to Leningrad at night, and was used for baking bread. When the city ran out of reserves of malt flour, other substitutes, such as finished cellulose and cotton-cake, were used. Oats meant for horses were also used, while the horses were fed wood leaves. When 2,000 tons of mutton guts had been found in the seaport, a food grade galantine was made of them. When the meat became unavailable, it was replaced by that galantine and by stinking[clarification needed] calf skins, which many survivors remembered until the end of their lives. During the first year of the siege, the city survived five food reductions: two reductions in September 1941, one in October, and two reductions in November. The latter reduced the daily food consumption to 250 grams daily for manual workers and 125 grams for other civilians.

The effects of starvation led to the consumption of zoo animals and household pets.[8] Much of the wallpaper paste in the buildings was made from potato starches. People began to strip the walls of rooms, removing the paste, and boiling it to make soup. Old leathers were also boiled and eaten.[8] The extreme hunger drove some to eat the corpses of the dead who had been largely preserved by the below freezing temperatures.[8] Reports of cannibalism began to appear in the winter of 1941–42 after all food sources were exhausted, but stayed comparatively low given the high amounts of starvation.[8] Meat patties, made from minced human flesh went on sale in the 'Haymarket' in November 1941,[9] leading to the banning of ground meat sales in the city.[8] Many bodies brought to cemeteries in the city were missing parts.[9] Starvation-level food rationing was eased by new vegetable gardens that covered most open ground in the city by 1942.[citation needed]

Civilian population evacuation

[edit]Almost all public transportation in Leningrad was destroyed as a result of massive air and artillery bombardments in August–September 1941. Three million people were trapped in the city. Leningrad, as a main military-industrial center in Russia, was populated by military-industrial engineers, technicians, and other workers with their civilian families. The only means of evacuation was on foot, with little opportunity to do so before the expected encirclement by the Wehrmacht and Finnish forces.

86 major strategic industries were evacuated from the city. Most industrial capacities, engines and power equipment, instruments and tools, were moved by the workers. Some defense industries, such as the LMZ, the Admiralty Shipyard, and the Kirov Plant, were left in the city, and were still producing armor and ammunition for the defenders.

Evacuation was organized by Kliment Voroshilov and Georgi Zhukov and was managed by engineers and workers of Leningrad's 86 major industries, which were themselves also evacuated from the city, by using every means of transportation available.

The evacuation operation was managed in several 'waves' or phases:

- The 'First wave' was from June to August 1941; 336,000 civilians, mostly children, managed to escape because they were taken in, and evacuated with the 86 industries that were dismantled and moved to Northern Russia and Siberia.

- The 'Second wave', from September 1941 to April 1942: involved 659,000 civilians who were evacuated mainly by watercraft and the ice road over lake Ladoga east of Leningrad.

- The 'Third wave', from May 1942 to October 1942: 403,000 civilians were evacuated, mainly through the waterways of lake Ladoga east of Leningrad.

The total number of civilians evacuated was about 1.4 million, mainly women, children and personnel essential to the war effort.[10]

Urban damage

[edit]Severe destruction of homes was caused by the Nazi bombing, as well as by daily artillery bombardments. Major destruction was done during August and September 1941, when artillery bombardments were almost constant for several weeks in a row. Regular bombing continued through 1941, 1942, and 1943. Most heavy artillery bombardments resumed in 1943, and increased six times in comparison with the beginning of the war. Hitler and the Nazi leadership were angered by their failure to take Leningrad by force. Hitler's directive No. 1601 ordered that "St. Petersburg must be erased from the face of the Earth" and "we have no interest in saving lives of the civilian population."[11]

The siege of Leningrad's blockade lasted about 900 days. The city sustained damage due to artillery attacks, air raids, and the struggle of famine. Although the city took significant damage, Alexander Werth, a Leningrad native, claims the city took less damage than any other major city affected by the war. Cities like Rotterdam, Warsaw, and Coventry sustained far more damage than Leningrad did. Leningrad suffered less damage than most German occupied USSR cities, such as Stalingrad, which later was burned to ashes. The damages might not be catastrophic, but they were significant, German artillery and bombers destroyed 16% of the city's housing. They also targeted their infrastructure, destroying streets and water and sewage pipes. Nearly half of the schools were wiped out and 78% of the hospitals. Not all houses were destroyed but every single structure had some kind of damage to it that gives each house a historic-artistic value.[12]

Since the city was blockaded, nothing could move in or out of the city. The only time people could get food delivered was when Lake Ladoga froze over and soldiers could come in to help the civilians. Public utilities were completely cut off from Leningrad.[13]

Aftermath

[edit]Following Germany's capitulation in May 1945, a concerted effort was made in Germany to search for the collections removed from the museums and palaces of Leningrad's surrounding areas during the war. In September 1945, the Leningrad Philharmonic returned to the city from Siberia, where it was evacuated during the war, to give its first peacetime concert performances. For the defense of the city and tenacity of the civilian survivors of the siege, Leningrad was the first city in the Soviet Union to be awarded the title of Hero City in 1945.

Siege commemoration

[edit]Economic and human losses caused incalculable damage to the city's historic sites and cultural landmarks, with much of the damage still visible today. Some ruins are preserved to commemorate those who gave their lives to save the city. As of 2007, there were still empty spaces in St. Petersburg suburbs where buildings had stood before the siege.

Siege influence on cultural expression

[edit]The siege caused major trauma for several generations after the war. Leningrad/St. Petersburg as the cultural capital, suffered incomparable human losses and the destruction of famous landmarks. While conditions in the city were appalling and starvation was constantly with the besieged, the city resisted for nearly three years.

The siege of Leningrad was commemorated in the late 1950s by the Green Belt of Glory, a circle of public parks and memorials along the historic front line. Warnings to citizens of the city as to which side of the road to walk on to avoid the German shelling can still be seen (they were restored after the war). Russian tour guides at Peterhof, the palaces near St. Petersburg, report that it is still dangerous to go for a stroll in the gardens during a thunderstorm, as German artillery shrapnel embedded in the trees attracts lightning.

The siege in music

[edit]- Dmitri Shostakovich wrote the Seventh Symphony, some of which was written under siege conditions, for the Leningrad Symphony. According to Solomon Volkov, whose testimony is disputed,[by whom?] Shostakovich said "it's not about Leningrad under siege, it's about the Leningrad that Stalin destroyed and that Hitler nearly finished off".

- American singer Billy Joel wrote a song called "Leningrad" that referred to the siege. The song is partially about a young Russian boy, Viktor, whose father has died.

- The Decemberists wrote a song called "When the War Came" about the heroism of civilian scientists. The lyrics state: "We made our oath to Vavilov/We'd not betray the solanum/The acres of asteraceae/To our own pangs of starvation". Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov was a Russian botanist whose laboratory, a seedbank containing 200,000 types of plant seeds, many of them edible, was preserved throughout the siege.

- Italian melodic death metal band Dark Lunacy's 2006 album 'The Diarist' is about the siege.

- A line in the song 'Scared', by the Canadian band 'The Tragically Hip', references Russian efforts to save paintings during the siege of Leningrad. "You're in Russia ... and more than a million works of art...are whisked out to the woods...When the Nazis find the whole place dark...they'd think God's left the museum for good."

- Dutch death metal band Hail of Bullets' song, "The Lake Ladoga Massacre", from their album "...Of Frost and War" is about the siege.

The Siege in literature

[edit]- Anna Akhmatova's Poem without Hero.

- American author Debra Dean's The Madonnas of Leningrad tells the story of staff of the Hermitage Museum who saved the art collection during the siege of Leningrad.

- American playwright, Ivan Fuller, wrote a three-play cycle about various art forms that helped people survive the siege. Eating into the Fabric focuses on a theatre company rehearsing Hamlet during the siege. Awake in Me is the story of poet and radio announcer, Olga Bergholz. In Every Note focuses on Shostakovich composing the Seventh Symphony before being evacuated from Leningrad.

- American author Elise Blackwell published a novel Hunger (2003), which provided an acclaimed historical dramatization of events surrounding the siege.

- British author Helen Dunmore wrote an award-winning novel, The Siege (2001). Although fictitious, it traces key events in the siege, and shows how it affected those who were not directly involved in the resistance.

- In 1981 Daniil Granin and Ales Adamovich published The Blockade Book which was based on hundreds of interviews and diaries of people who were trapped in the besieged city. The book was heavily censored by the Soviet authorities due to its portrayal of human suffering contrasting with the "official" image of heroism.

- In Boris Strugatsky's book Search for Destiny or the Twenty Seventh Theorem of Ethics the author describes his childhood memories of the Siege (in the chapter "A Happy Boy").

- Kyra Petrovskaya Wayne, a Russian soldier and, later, writer, illustrated life in besieged Leningrad in Shurik: A Story of the Siege of Leningrad, which tells the story of an orphan whom Petrovskaya found and cared for during the siege.

- Cory Doctorow's After The Siege is a science fiction story influenced by the author's grandmother's experiences during the siege.

- City of Thieves by American writer David Benioff takes place in besieged Leningrad and its surroundings; it tells the story of two young Russians tasked with finding eggs by an NKVD colonel within six days.

- Gillian Slovo's Ice Road written in 2004 is a fictional account of Leningraders from 1933 to during the siege. It has historical references and focuses on a number of people's quest for survival.

- The Bronze Horseman by Paullina Simons, a novel about a young girl and her family. She lost all her family during the Siege.

- The Arab-Israeli author Emil Habibi also mentioned the siege in his short story The Love in my Heart (الحب في قلبي), part of his collection Sextet of the Six Days (سداسية الايام الستة). Habiby's character visits a graveyard containing the siege's victims and is struck by the power of a display he sees commemorating the children who died, it inspires him to write some letters in the voice of a Palestinian girl detained in an Israeli prison.

- Ilya Mikson wrote a book inspired by the story and life of Tanya Savicheva.[14]

- Catherynne M. Valente's Deathless, a 20th-century retelling of a Russian fairy tale, is set partly in Leningrad during the siege. Valente quotes Anna Akhmatova's poetry throughout the novel.

The siege in other art forms

[edit]- Auteur film director Andrey Tarkovsky included multiple scenes and references to the siege in his semi-autobiographical film The Mirror.

- At the time of his death in 1989, Sergio Leone was working on a film about the siege. It drew heavily on Harrison Salisbury's "The 900 Days", and was a week away from going into production when Leone died of heart failure.

- Alexander Sokurov's 2002 film Russian Ark includes a segment which depicts a city resident building his own coffin during the siege.

There are two monuments to foodstuff animals contributed to the survival of Leningraders: ru:Памятник тюленю ru:Памятник блокадной колюшке.

Notable survivors of the siege

[edit]- Anna Akhmatova – poet and writer

- Boris Babochkin – actor, director

- Olga Berggoltz – poet and writer, decorated for her courage

- Joseph Brodsky – poet, Nobel Prize laureate

- Bruno Freindlich – actor

- Alisa Freindlich – actress

- Vera Inber – poet, writer

- Viktor Korchnoi – chess grandmaster

- Grigori Kozintsev – film director, decorated for his courage

- Evgeny Mravinsky – conductor, pianist, and music pedagogue

- Alexander Ney - artist

- Nikolai Cherkasov – actor

- Nikolai Punin – curator of the Russian Museum and the Hermitage Museum

- Dmitry Shostakovich – composer, decorated for his courage

- Boris Strugatskiy – science fiction writer

- Mark Taimanov – chess grandmaster

- Galina Vishnevskaya – opera singer

- Kyra Petrovskaya Wayne – soldier/sniper and writer

See also

[edit]- Hunger Plan

- Tanya Savicheva

- World War II casualties

- List of famines

- Dutch famine of 1944

- Siege of Sarajevo

References

[edit]- ^ Schoppert, Stephanie (1 December 2016). "Eight Horrific Facts About the Siege of Leningrad 1941-1944". History Collection. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Rotar, Oxana P.; Moguchaya, Ekaterina V.; Boyarinova, Maria A.; Alieva, Asilat S.; Orlov, Alexander V.; Vasilieva, Elena Y.; Yudina, Victoria A.; Anisimov, Sergey V.; Konradi, Alexandra O. (2015). "Siege of Leningrad Survivors Phenotyping and Biospecimen Collection". Biopreservation and Biobanking. 13 (5): 371–375. doi:10.1089/bio.2015.0018. ISSN 1947-5543. PMID 26417917.

- ^ Salisbury, Harrison E. (1969). The 900 Days: The Siege Of Leningrad. HarperCollins. p. 594. ISBN 978-0060137328.

- ^ Vågerö, Denny; Koupil, Ilona; Parfenova, Nina; Sparen, Pär (2013), Long-term health consequences following the siege of Leningrad, Nova Science Publishers, Inc., pp. 207–225, retrieved 2024-03-31

- ^ Dondo, William A. (2012). "Russia and Soviet Famines 971-1947". In Dondo, William A. (ed.). Food and Famine in the 21st Century, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 27. ISBN 978-1598847307.

- ^ Reagan, Geoffrey (1992). Military Anecdotes. Guinness Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 0-85112-519-0.

- ^ Hartman, Carl (April 26, 1992). "Seed Bank Survived Leningrad Siege; Now, Budget Is The Threat". Philly.com. Associated Press. Retrieved 2015-12-15.

Fifty years ago last winter, Dmitry S. Ivanov, who kept the rice collection at one of the world's biggest seed banks, died of starvation at his post during the siege of Leningrad in World War II. After his death, workmen found several thousand packs of rice that he had preserved. A.G. Stchukin, a specialist in peanuts, died at his desk. Liliya M. Rodina, keeper of the oat collection, and more than half a dozen others also succumbed. They all refused to eat from any of their collections of rice, peas, corn and wheat.

- ^ a b c d e Todd Tucker (2007), The Great Starvation Experiment: Ancel Keys and the Men Who Starved for Science, Free Press, New York, pp. 7–9, ISBN 978-0816651610

- ^ a b Reagan, p. 77

- ^ "Road of Life (Russian commemoration of 65th Anniversary of the siege of Leningrad)" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2008-02-28.

- ^ Hitler, Adolf (1941-09-22). "Directive No. 1601" (in Russian).

- ^ Kirschenbaum, Lisa (2011). "Remembering and Rebuilding: Leningrad after the Siege from a Comparative Perspective". Journal of Modern European History. 9 (3): 314–327. doi:10.17104/1611-8944_2011_3_314. ISSN 1611-8944. JSTOR 26265946. S2CID 147596054.

- ^ "Siege of Leningrad begins". HISTORY. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- ^ Миксон, Илья Львович (1991). Жила-была (in Russian). Leningrad: Detskaya Literatura. p. 219. ISBN 5-08-000008-2. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Barber, John; Dzeniskevich, Andrei (2005), Life and Death in Besieged Leningrad, 1941–44, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, ISBN 978-1-4039-0142-2

- Baryshnikov, N. I. (2003), Блокада Ленинграда и Финляндия 1941–44 (Finland and the siege of Leningrad), Институт Йохана Бекмана

- Glantz, David (2001), The Siege of Leningrad 1941–44: 900 Days of Terror, Zenith Press, Osceola, WI, ISBN 978-0-7603-0941-4

- Goure, Leon (1981), The Siege of Leningrad, Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, CA, ISBN 978-0-8047-0115-0

- Kirschenbaum, Lisa (2006), The Legacy of the Siege of Leningrad, 1941–1995: Myth, Memories, and Monuments, Cambridge University Press, New York, ISBN 978-0-521-86326-1

- Lubbeck, William; Hurt, David B. (2006), At Leningrad's Gates: The Story of a Soldier with Army Group North, Casemate, Philadelphia, PA, ISBN 978-1-932033-55-7

- Salisbury, Harrison Evans (1969), The 900 Days: The Siege of Leningrad, Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-0-306-81298-9

- Simmons, Cynthia; Perlina, Nina (2005), Writing the Siege of Leningrad. Women's diaries, Memories, and Documentary Prose, University of Pittsburgh Press, ISBN 978-0-8229-5869-7

- Willmott, H. P.; Cross, Robin; Messenger, Charles (2004), The Siege of Leningrad in World War II, Dorling Kindersley, ISBN 978-0-7566-2968-7

- Wykes, Alan (1972), The Siege of Leningrad, Ballantines Illustrated History of WWII

- Backlund, L. S.: Nazi Germany and Finland. University of Pennsylvania, 1983. University Microfilms International A. Bell & Howell Information Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

- BARBAROSSA. By Alan Clark. Perennial, 2002. ISBN 978-0-688-04268-4

- Baryshnikov, N. I. and Baryshnikov, V. N.: 'Terijoen hallitus', TPH 1997. pp. 173–184.

- Baryshnikov, N. I., Baryshnikov, V. N. and Fedorov, V. G.: Finland in the Second World War (in Russian: Финляндия во второй мировой войне). Leningrad. Lenizdat, 1989.

- Baryshnikov, N. I. and Manninen, O.: 'Sodan aattona', TPH 1997. pp. 127–138.

- Baryshnikov, V. N.: 'Neuvostoliiton Suomen suhteiden kehitys sotaa edeltaneella kaudella', TPH 1997, pp. 7–87.

- Балтийский Флот. Гречанюк Н. М., Дмитриев В. И., Корниенко А. И. и др., М., Воениздат. 1990.

- Cartier, Raymond (1977). Der Zweite Weltkrieg. München, Zürich: R. Piper & CO. Verlag. 1141 pages.

- "Finland throws its lot with Germany". Finland in the Second World War. Berghahn Books. 2006.

- Константин Симонов, Записи бесед с Г. К. Жуковым 1965–1966 — Simonov, Konstantin (1979). "Records of talks with Georgi Zhukov, 1965–1966". Hrono.

- Vehviläinen, Olli. Translated by Gerard McAlister. Finland in the Second World War between Germany and Russia. Palgrave. 2002.

- Kay, Alex J. (2006): Exploitation, Resettlement, Mass Murder. Political and Economic Planning for German Occupation Policy in the Soviet Union, 1940–1941. Berghahn Books. New York, Oxford.

- Higgins, Trumbull. Hitler and Russia. The Macmillan Company, 1966.

- Fugate, Bryan I. Operation Barbarossa. Strategy and Tactics on the Eastern Front, 1941. 415 pages. Presidio Press (July 1984) ISBN 978-0-89141-197-0.

- Winston S. Churchill. Memoires of the Second World War. An abridgment of the six volumes of The Second World War. By Houghton Mifflin Company. Boston. ISBN 978-0-395-59968-6.

- Russia Besieged (World War II). By Bethel, Nicholas and the editors of Time-Life Books. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books 1981. 4th Printing, Revised.

- The World War II. Desk Reference. Eisenhower Center director Douglas Brinkley. Editor Mickael E. Haskey. Grand Central Press, 2004.

- The story of World War II. By Donald L. Miller. Simon & Schuster, 2006. ISBN 978-0-7432-2718-6.

External links

[edit]| External images | |

|---|---|

| the Siege of Leningrad | |

- ^ ОТЕЧЕСТВЕННАЯ ИСТОРИЯ. Тема 8 (in Russian). Ido.edu.ru. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ^ Фотогалерея: "От Волги До Берлина. Основные операции советской армии, завершившие разгром врага." (in Russian). victory.tass-online.ru (ИТАР-ТАСС). Retrieved 2008-10-26.