Polygon

In geometry, a polygon (/ˈpɒlɪɡɒn/) is a plane figure made up of line segments connected to form a closed polygonal chain.

The segments of a closed polygonal chain are called its edges or sides. The points where two edges meet are the polygon's vertices or corners. An n-gon is a polygon with n sides; for example, a triangle is a 3-gon.

A simple polygon is one which does not intersect itself. More precisely, the only allowed intersections among the line segments that make up the polygon are the shared endpoints of consecutive segments in the polygonal chain. A simple polygon is the boundary of a region of the plane that is called a solid polygon. The interior of a solid polygon is its body, also known as a polygonal region or polygonal area. In contexts where one is concerned only with simple and solid polygons, a polygon may refer only to a simple polygon or to a solid polygon.

A polygonal chain may cross over itself, creating star polygons and other self-intersecting polygons. Some sources also consider closed polygonal chains in Euclidean space to be a type of polygon (a skew polygon), even when the chain does not lie in a single plane.

A polygon is a 2-dimensional example of the more general polytope in any number of dimensions. There are many more generalizations of polygons defined for different purposes.

Etymology

The word polygon derives from the Greek adjective πολύς (polús) 'much', 'many' and γωνία (gōnía) 'corner' or 'angle'. It has been suggested that γόνυ (gónu) 'knee' may be the origin of gon.[1]

Classification

Number of sides

Polygons are primarily classified by the number of sides.

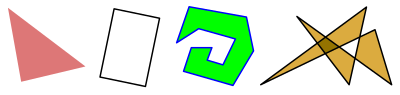

Convexity and intersection

Polygons may be characterized by their convexity or type of non-convexity:

- Convex: any line drawn through the polygon (and not tangent to an edge or corner) meets its boundary exactly twice. As a consequence, all its interior angles are less than 180°. Equivalently, any line segment with endpoints on the boundary passes through only interior points between its endpoints. This condition is true for polygons in any geometry, not just Euclidean.[2]

- Non-convex: a line may be found which meets its boundary more than twice. Equivalently, there exists a line segment between two boundary points that passes outside the polygon.

- Simple: the boundary of the polygon does not cross itself. All convex polygons are simple.

- Concave: Non-convex and simple. There is at least one interior angle greater than 180°.

- Star-shaped: the whole interior is visible from at least one point, without crossing any edge. The polygon must be simple, and may be convex or concave. All convex polygons are star-shaped.

- Self-intersecting: the boundary of the polygon crosses itself. The term complex is sometimes used in contrast to simple, but this usage risks confusion with the idea of a complex polygon as one which exists in the complex Hilbert plane consisting of two complex dimensions.

- Star polygon: a polygon which self-intersects in a regular way. A polygon cannot be both a star and star-shaped.

Equality and symmetry

- Equiangular: all corner angles are equal.

- Equilateral: all edges are of the same length.

- Regular: both equilateral and equiangular.

- Cyclic: all corners lie on a single circle, called the circumcircle.

- Tangential: all sides are tangent to an inscribed circle.

- Isogonal or vertex-transitive: all corners lie within the same symmetry orbit. The polygon is also cyclic and equiangular.

- Isotoxal or edge-transitive: all sides lie within the same symmetry orbit. The polygon is also equilateral and tangential.

The property of regularity may be defined in other ways: a polygon is regular if and only if it is both isogonal and isotoxal, or equivalently it is both cyclic and equilateral. A non-convex regular polygon is called a regular star polygon.

Miscellaneous

- Rectilinear: the polygon's sides meet at right angles, i.e. all its interior angles are 90 or 270 degrees.

- Monotone with respect to a given line L: every line orthogonal to L intersects the polygon not more than twice.

Properties and formulas

Euclidean geometry is assumed throughout.

Angles

Any polygon has as many corners as it has sides. Each corner has several angles. The two most important ones are:

- Interior angle – The sum of the interior angles of a simple n-gon is (n − 2) × π radians or (n − 2) × 180 degrees. This is because any simple n-gon ( having n sides ) can be considered to be made up of (n − 2) triangles, each of which has an angle sum of π radians or 180 degrees. The measure of any interior angle of a convex regular n-gon is radians or degrees. The interior angles of regular star polygons were first studied by Poinsot, in the same paper in which he describes the four regular star polyhedra: for a regular -gon (a p-gon with central density q), each interior angle is radians or degrees.[3]

- Exterior angle – The exterior angle is the supplementary angle to the interior angle. Tracing around a convex n-gon, the angle "turned" at a corner is the exterior or external angle. Tracing all the way around the polygon makes one full turn, so the sum of the exterior angles must be 360°. This argument can be generalized to concave simple polygons, if external angles that turn in the opposite direction are subtracted from the total turned. Tracing around an n-gon in general, the sum of the exterior angles (the total amount one rotates at the vertices) can be any integer multiple d of 360°, e.g. 720° for a pentagram and 0° for an angular "eight" or antiparallelogram, where d is the density or turning number of the polygon.

Area

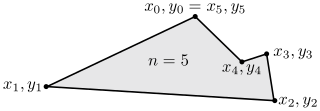

In this section, the vertices of the polygon under consideration are taken to be in order. For convenience in some formulas, the notation (xn, yn) = (x0, y0) will also be used.

Simple polygons

If the polygon is non-self-intersecting (that is, simple), the signed area is

or, using determinants

where is the squared distance between and [4][5]

The signed area depends on the ordering of the vertices and of the orientation of the plane. Commonly, the positive orientation is defined by the (counterclockwise) rotation that maps the positive x-axis to the positive y-axis. If the vertices are ordered counterclockwise (that is, according to positive orientation), the signed area is positive; otherwise, it is negative. In either case, the area formula is correct in absolute value. This is commonly called the shoelace formula or surveyor's formula.[6]

The area A of a simple polygon can also be computed if the lengths of the sides, a1, a2, ..., an and the exterior angles, θ1, θ2, ..., θn are known, from:

The formula was described by Lopshits in 1963.[7]

If the polygon can be drawn on an equally spaced grid such that all its vertices are grid points, Pick's theorem gives a simple formula for the polygon's area based on the numbers of interior and boundary grid points: the former number plus one-half the latter number, minus 1.

In every polygon with perimeter p and area A , the isoperimetric inequality holds.[8]

For any two simple polygons of equal area, the Bolyai–Gerwien theorem asserts that the first can be cut into polygonal pieces which can be reassembled to form the second polygon.

The lengths of the sides of a polygon do not in general determine its area.[9] However, if the polygon is simple and cyclic then the sides do determine the area.[10] Of all n-gons with given side lengths, the one with the largest area is cyclic. Of all n-gons with a given perimeter, the one with the largest area is regular (and therefore cyclic).[11]

Regular polygons

Many specialized formulas apply to the areas of regular polygons.

The area of a regular polygon is given in terms of the radius r of its inscribed circle and its perimeter p by

This radius is also termed its apothem and is often represented as a.

The area of a regular n-gon in terms of the radius R of its circumscribed circle can be expressed trigonometrically as:[12][13]

The area of a regular n-gon inscribed in a unit-radius circle, with side s and interior angle can also be expressed trigonometrically as:

Self-intersecting

The area of a self-intersecting polygon can be defined in two different ways, giving different answers:

- Using the formulas for simple polygons, we allow that particular regions within the polygon may have their area multiplied by a factor which we call the density of the region. For example, the central convex pentagon in the center of a pentagram has density 2. The two triangular regions of a cross-quadrilateral (like a figure 8) have opposite-signed densities, and adding their areas together can give a total area of zero for the whole figure.[14]

- Considering the enclosed regions as point sets, we can find the area of the enclosed point set. This corresponds to the area of the plane covered by the polygon or to the area of one or more simple polygons having the same outline as the self-intersecting one. In the case of the cross-quadrilateral, it is treated as two simple triangles.[citation needed]

Centroid

Using the same convention for vertex coordinates as in the previous section, the coordinates of the centroid of a solid simple polygon are

In these formulas, the signed value of area must be used.

For triangles (n = 3), the centroids of the vertices and of the solid shape are the same, but, in general, this is not true for n > 3. The centroid of the vertex set of a polygon with n vertices has the coordinates

Generalizations

The idea of a polygon has been generalized in various ways. Some of the more important include:

- A spherical polygon is a circuit of arcs of great circles (sides) and vertices on the surface of a sphere. It allows the digon, a polygon having only two sides and two corners, which is impossible in a flat plane. Spherical polygons play an important role in cartography (map making) and in Wythoff's construction of the uniform polyhedra.

- A skew polygon does not lie in a flat plane, but zigzags in three (or more) dimensions. The Petrie polygons of the regular polytopes are well known examples.

- An apeirogon is an infinite sequence of sides and angles, which is not closed but has no ends because it extends indefinitely in both directions.

- A skew apeirogon is an infinite sequence of sides and angles that do not lie in a flat plane.

- A polygon with holes is an area-connected or multiply-connected planar polygon with one external boundary and one or more interior boundaries (holes).

- A complex polygon is a configuration analogous to an ordinary polygon, which exists in the complex plane of two real and two imaginary dimensions.

- An abstract polygon is an algebraic partially ordered set representing the various elements (sides, vertices, etc.) and their connectivity. A real geometric polygon is said to be a realization of the associated abstract polygon. Depending on the mapping, all the generalizations described here can be realized.

- A polyhedron is a three-dimensional solid bounded by flat polygonal faces, analogous to a polygon in two dimensions. The corresponding shapes in four or higher dimensions are called polytopes.[15] (In other conventions, the words polyhedron and polytope are used in any dimension, with the distinction between the two that a polytope is necessarily bounded.[16])

Naming

The word polygon comes from Late Latin polygōnum (a noun), from Greek πολύγωνον (polygōnon/polugōnon), noun use of neuter of πολύγωνος (polygōnos/polugōnos, the masculine adjective), meaning "many-angled". Individual polygons are named (and sometimes classified) according to the number of sides, combining a Greek-derived numerical prefix with the suffix -gon, e.g. pentagon, dodecagon. The triangle, quadrilateral and nonagon are exceptions.

Beyond decagons (10-sided) and dodecagons (12-sided), mathematicians generally use numerical notation, for example 17-gon and 257-gon.[17]

Exceptions exist for side counts that are easily expressed in verbal form (e.g. 20 and 30), or are used by non-mathematicians. Some special polygons also have their own names; for example the regular star pentagon is also known as the pentagram.

| Name | Sides | Properties |

|---|---|---|

| monogon | 1 | Not generally recognised as a polygon,[18] although some disciplines such as graph theory sometimes use the term.[19] |

| digon | 2 | Not generally recognised as a polygon in the Euclidean plane, although it can exist as a spherical polygon.[20] |

| triangle (or trigon) | 3 | The simplest polygon which can exist in the Euclidean plane. Can tile the plane. |

| quadrilateral (or tetragon) | 4 | The simplest polygon which can cross itself; the simplest polygon which can be concave; the simplest polygon which can be non-cyclic. Can tile the plane. |

| pentagon | 5 | [21] The simplest polygon which can exist as a regular star. A star pentagon is known as a pentagram or pentacle. |

| hexagon | 6 | [21] Can tile the plane. |

| heptagon (or septagon) | 7 | [21] The simplest polygon such that the regular form is not constructible with compass and straightedge. However, it can be constructed using a neusis construction. |

| octagon | 8 | [21] |

| nonagon (or enneagon) | 9 | [21]"Nonagon" mixes Latin [novem = 9] with Greek; "enneagon" is pure Greek. |

| decagon | 10 | [21] |

| hendecagon (or undecagon) | 11 | [21] The simplest polygon such that the regular form cannot be constructed with compass, straightedge, and angle trisector. However, it can be constructed with neusis.[22] |

| dodecagon (or duodecagon) | 12 | [21] |

| tridecagon (or triskaidecagon) | 13 | [21] |

| tetradecagon (or tetrakaidecagon) | 14 | [21] |

| pentadecagon (or pentakaidecagon) | 15 | [21] |

| hexadecagon (or hexakaidecagon) | 16 | [21] |

| heptadecagon (or heptakaidecagon) | 17 | Constructible polygon[17] |

| octadecagon (or octakaidecagon) | 18 | [21] |

| enneadecagon (or enneakaidecagon) | 19 | [21] |

| icosagon | 20 | [21] |

| icositrigon (or icosikaitrigon) | 23 | The simplest polygon such that the regular form cannot be constructed with neusis.[23][22] |

| icositetragon (or icosikaitetragon) | 24 | [21] |

| icosipentagon (or icosikaipentagon) | 25 | The simplest polygon such that it is not known if the regular form can be constructed with neusis or not.[23][22] |

| triacontagon | 30 | [21] |

| tetracontagon (or tessaracontagon) | 40 | [21][24] |

| pentacontagon (or pentecontagon) | 50 | [21][24] |

| hexacontagon (or hexecontagon) | 60 | [21][24] |

| heptacontagon (or hebdomecontagon) | 70 | [21][24] |

| octacontagon (or ogdoëcontagon) | 80 | [21][24] |

| enneacontagon (or enenecontagon) | 90 | [21][24] |

| hectogon (or hecatontagon)[25] | 100 | [21] |

| 257-gon | 257 | Constructible polygon[17] |

| chiliagon | 1000 | Philosophers including René Descartes,[26] Immanuel Kant,[27] David Hume,[28] have used the chiliagon as an example in discussions. |

| myriagon | 10,000 | Used as an example in some philosophical discussions, for example in Descartes's Meditations on First Philosophy |

| 65537-gon | 65,537 | Constructible polygon[17] |

| megagon[29][30][31] | 1,000,000 | As with René Descartes's example of the chiliagon, the million-sided polygon has been used as an illustration of a well-defined concept that cannot be visualised.[32][33][34][35][36][37][38] The megagon is also used as an illustration of the convergence of regular polygons to a circle.[39] |

| apeirogon | ∞ | A degenerate polygon of infinitely many sides. |

To construct the name of a polygon with more than 20 and fewer than 100 edges, combine the prefixes as follows.[21] The "kai" term applies to 13-gons and higher and was used by Kepler, and advocated by John H. Conway for clarity of concatenated prefix numbers in the naming of quasiregular polyhedra,[25] though not all sources use it.

| Tens | and | Ones | final suffix | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -kai- | 1 | -hena- | -gon | ||

| 20 | icosi- (icosa- when alone) | 2 | -di- | ||

| 30 | triaconta- (or triconta-) | 3 | -tri- | ||

| 40 | tetraconta- (or tessaraconta-) | 4 | -tetra- | ||

| 50 | pentaconta- (or penteconta-) | 5 | -penta- | ||

| 60 | hexaconta- (or hexeconta-) | 6 | -hexa- | ||

| 70 | heptaconta- (or hebdomeconta-) | 7 | -hepta- | ||

| 80 | octaconta- (or ogdoëconta-) | 8 | -octa- | ||

| 90 | enneaconta- (or eneneconta-) | 9 | -ennea- | ||

History

Polygons have been known since ancient times. The regular polygons were known to the ancient Greeks, with the pentagram, a non-convex regular polygon (star polygon), appearing as early as the 7th century B.C. on a krater by Aristophanes, found at Caere and now in the Capitoline Museum.[40][41]

The first known systematic study of non-convex polygons in general was made by Thomas Bradwardine in the 14th century.[42]

In 1952, Geoffrey Colin Shephard generalized the idea of polygons to the complex plane, where each real dimension is accompanied by an imaginary one, to create complex polygons.[43]

In nature

Polygons appear in rock formations, most commonly as the flat facets of crystals, where the angles between the sides depend on the type of mineral from which the crystal is made.

Regular hexagons can occur when the cooling of lava forms areas of tightly packed columns of basalt, which may be seen at the Giant's Causeway in Northern Ireland, or at the Devil's Postpile in California.

In biology, the surface of the wax honeycomb made by bees is an array of hexagons, and the sides and base of each cell are also polygons.

Computer graphics

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2018) |

In computer graphics, a polygon is a primitive used in modelling and rendering. They are defined in a database, containing arrays of vertices (the coordinates of the geometrical vertices, as well as other attributes of the polygon, such as color, shading and texture), connectivity information, and materials.[44][45]

Any surface is modelled as a tessellation called polygon mesh. If a square mesh has n + 1 points (vertices) per side, there are n squared squares in the mesh, or 2n squared triangles since there are two triangles in a square. There are (n + 1)2 / 2(n2) vertices per triangle. Where n is large, this approaches one half. Or, each vertex inside the square mesh connects four edges (lines).

The imaging system calls up the structure of polygons needed for the scene to be created from the database. This is transferred to active memory and finally, to the display system (screen, TV monitors etc.) so that the scene can be viewed. During this process, the imaging system renders polygons in correct perspective ready for transmission of the processed data to the display system. Although polygons are two-dimensional, through the system computer they are placed in a visual scene in the correct three-dimensional orientation.

In computer graphics and computational geometry, it is often necessary to determine whether a given point lies inside a simple polygon given by a sequence of line segments. This is called the point in polygon test.[46]

See also

References

Bibliography

- Coxeter, H.S.M.; Regular Polytopes, Methuen and Co., 1948 (3rd Edition, Dover, 1973).

- Cromwell, P.; Polyhedra, CUP hbk (1997), pbk. (1999).

- Grünbaum, B.; Are your polyhedra the same as my polyhedra? Discrete and comput. geom: the Goodman-Pollack festschrift, ed. Aronov et al. Springer (2003) pp. 461–488. (pdf)

Notes

- ^ Craig, John (1849). A new universal etymological technological, and pronouncing dictionary of the English language. Oxford University. p. 404. Extract of p. 404

- ^ Magnus, Wilhelm (1974). Noneuclidean tesselations and their groups. Pure and Applied Mathematics. Vol. 61. Academic Press. p. 37.

- ^ Kappraff, Jay (2002). Beyond measure: a guided tour through nature, myth, and number. World Scientific. p. 258. ISBN 978-981-02-4702-7.

- ^ B.Sz. Nagy, L. Rédey: Eine Verallgemeinerung der Inhaltsformel von Heron. Publ. Math. Debrecen 1, 42–50 (1949)

- ^ Bourke, Paul (July 1988). "Calculating The Area And Centroid Of A Polygon" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2012. Retrieved 6 Feb 2013.

- ^ Bart Braden (1986). "The Surveyor's Area Formula" (PDF). The College Mathematics Journal. 17 (4): 326–337. doi:10.2307/2686282. JSTOR 2686282. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-07.

- ^ A.M. Lopshits (1963). Computation of areas of oriented figures. translators: J Massalski and C Mills Jr. D C Heath and Company: Boston, MA.

- ^ "Dergiades, Nikolaos, "An elementary proof of the isoperimetric inequality", Forum Mathematicorum 2, 2002, 129–130" (PDF).

- ^ Robbins, "Polygons inscribed in a circle", American Mathematical Monthly 102, June–July 1995.

- ^ Pak, Igor (2005). "The area of cyclic polygons: recent progress on Robbins' conjectures". Advances in Applied Mathematics. 34 (4): 690–696. arXiv:math/0408104. doi:10.1016/j.aam.2004.08.006. MR 2128993. S2CID 6756387.

- ^ Chakerian, G. D. "A Distorted View of Geometry." Ch. 7 in Mathematical Plums (R. Honsberger, editor). Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America, 1979: 147.

- ^ Area of a regular polygon – derivation from Math Open Reference.

- ^ A regular polygon with an infinite number of sides is a circle: .

- ^ De Villiers, Michael (January 2015). "Slaying a geometrical 'Monster': finding the area of a crossed Quadrilateral" (PDF). Learning and Teaching Mathematics. 2015 (18): 23–28.

- ^ Coxeter (3rd Ed 1973)

- ^ Günter Ziegler (1995). "Lectures on Polytopes". Springer Graduate Texts in Mathematics, ISBN 978-0-387-94365-7. p. 4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Mathworld

- ^ Grunbaum, B.; "Are your polyhedra the same as my polyhedra", Discrete and computational geometry: the Goodman-Pollack Festschrift, Ed. Aronov et al., Springer (2003), p. 464.

- ^ Hass, Joel; Morgan, Frank (1996). "Geodesic nets on the 2-sphere". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 124 (12): 3843–3850. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-96-03492-2. JSTOR 2161556. MR 1343696.

- ^ Coxeter, H.S.M.; Regular polytopes, Dover Edition (1973), p. 4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Salomon, David (2011). The Computer Graphics Manual. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 88–90. ISBN 978-0-85729-886-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Benjamin, Elliot; Snyder, C. Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 156.3 (May 2014): 409–424.; https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0305004113000753

- ^ Jump up to: a b Arthur Baragar (2002) Constructions Using a Compass and Twice-Notched Straightedge, The American Mathematical Monthly, 109:2, 151–164, doi:10.1080/00029890.2002.11919848

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f The New Elements of Mathematics: Algebra and Geometry by Charles Sanders Peirce (1976), p.298

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Naming Polygons and Polyhedra". Ask Dr. Math. The Math Forum – Drexel University. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Sepkoski, David (2005). "Nominalism and constructivism in seventeenth-century mathematical philosophy". Historia Mathematica. 32: 33–59. doi:10.1016/j.hm.2003.09.002.

- ^ Gottfried Martin (1955), Kant's Metaphysics and Theory of Science, Manchester University Press, p. 22.

- ^ David Hume, The Philosophical Works of David Hume, Volume 1, Black and Tait, 1826, p. 101.

- ^ Gibilisco, Stan (2003). Geometry demystified (Online-Ausg. ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-141650-4.

- ^ Darling, David J., The universal book of mathematics: from Abracadabra to Zeno's paradoxes, John Wiley & Sons, 2004. p. 249. ISBN 0-471-27047-4.

- ^ Dugopolski, Mark, College Algebra and Trigonometry, 2nd ed, Addison-Wesley, 1999. p. 505. ISBN 0-201-34712-1.

- ^ McCormick, John Francis, Scholastic Metaphysics, Loyola University Press, 1928, p. 18.

- ^ Merrill, John Calhoun and Odell, S. Jack, Philosophy and Journalism, Longman, 1983, p. 47, ISBN 0-582-28157-1.

- ^ Hospers, John, An Introduction to Philosophical Analysis, 4th ed, Routledge, 1997, p. 56, ISBN 0-415-15792-7.

- ^ Mandik, Pete, Key Terms in Philosophy of Mind, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2010, p. 26, ISBN 1-84706-349-7.

- ^ Kenny, Anthony, The Rise of Modern Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 2006, p. 124, ISBN 0-19-875277-6.

- ^ Balmes, James, Fundamental Philosophy, Vol II, Sadlier and Co., Boston, 1856, p. 27.

- ^ Potter, Vincent G., On Understanding Understanding: A Philosophy of Knowledge, 2nd ed, Fordham University Press, 1993, p. 86, ISBN 0-8232-1486-9.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand, History of Western Philosophy, reprint edition, Routledge, 2004, p. 202, ISBN 0-415-32505-6.

- ^ Heath, Sir Thomas Little (1981). A History of Greek Mathematics, Volume 1. Courier Dover Publications. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-486-24073-2. Reprint of original 1921 publication with corrected errata. Heath uses the Latinized spelling "Aristophonus" for the vase painter's name.

- ^ Cratere with the blinding of Polyphemus and a naval battle Archived 2013-11-12 at the Wayback Machine, Castellani Halls, Capitoline Museum, accessed 2013-11-11. Two pentagrams are visible near the center of the image,

- ^ Coxeter, H.S.M.; Regular Polytopes, 3rd Edn, Dover (pbk), 1973, p. 114

- ^ Shephard, G.C.; "Regular complex polytopes", Proc. London Math. Soc. Series 3 Volume 2, 1952, pp 82–97

- ^ "opengl vertex specification".

- ^ "direct3d rendering, based on vertices & triangles".

- ^ Schirra, Stefan (2008). "How Reliable Are Practical Point-in-Polygon Strategies?". In Halperin, Dan; Mehlhorn, Kurt (eds.). Algorithms - ESA 2008: 16th Annual European Symposium, Karlsruhe, Germany, September 15-17, 2008, Proceedings. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5193. Springer. pp. 744–755. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-87744-8_62.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Polygon". MathWorld.

- What Are Polyhedra?, with Greek Numerical Prefixes

- Polygons, types of polygons, and polygon properties, with interactive animation

- How to draw monochrome orthogonal polygons on screens, by Herbert Glarner

- comp.graphics.algorithms Frequently Asked Questions, solutions to mathematical problems computing 2D and 3D polygons

- Comparison of the different algorithms for Polygon Boolean operations, compares capabilities, speed and numerical robustness

- Interior angle sum of polygons: a general formula, Provides an interactive Java investigation that extends the interior angle sum formula for simple closed polygons to include crossed (complex) polygons

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}A={\frac {1}{2}}(a_{1}[a_{2}\sin(\theta _{1})+a_{3}\sin(\theta _{1}+\theta _{2})+\cdots +a_{n-1}\sin(\theta _{1}+\theta _{2}+\cdots +\theta _{n-2})]\\{}+a_{2}[a_{3}\sin(\theta _{2})+a_{4}\sin(\theta _{2}+\theta _{3})+\cdots +a_{n-1}\sin(\theta _{2}+\cdots +\theta _{n-2})]\\{}+\cdots +a_{n-2}[a_{n-1}\sin(\theta _{n-2})]).\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/782046e07ca487a9d555c83a434d7c13aaf01c31)