Broughton Suspension Bridge

Broughton Suspension Bridge | |

|---|---|

The rebuilt Broughton suspension bridge in 1883 | |

| Coordinates | 53°29′46″N 2°16′12″W / 53.4961°N 2.27°W |

| Crossed | River Irwell |

| Locale | Broughton |

| History | |

| Constructed by | Samuel Brown |

| Opened | 1826 |

| Collapsed | 12 April 1831 |

| Replaced by | Pratt truss footbridge |

| Location | |

| |

Broughton Suspension Bridge was an iron chain suspension bridge built in 1826 to span the River Irwell between Broughton and Pendleton, now in Salford, Greater Manchester, England. One of Europe's first suspension bridges, it has been attributed to Samuel Brown, although some suggest it was built by Thomas Cheek Hewes, a Manchester millwright and textile machinery manufacturer.[1][2]

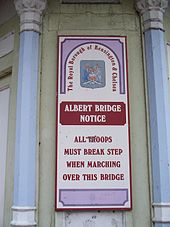

On 12 April 1831, the bridge collapsed, reportedly due to mechanical resonance induced by troops marching in step.[3] As a result of the incident, the British Army issued an order that troops should "break step" when crossing a bridge. Although rebuilt and strengthened, the bridge was subsequently propped with temporary piles whenever crowds were expected. In 1924, it was replaced by a Pratt truss footbridge, still in use.

Construction

[edit]In 1826, John Fitzgerald, the wealthy owner of Castle Irwell House (later to become the site of the Manchester Racecourse), built, at his own expense, a 144 feet (44 m) suspension bridge across the River Irwell between Lower Broughton and Pendleton. According to John Marius Wilson's Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales (1870–72) all users of the bridge were required to pay a pontage to cross.[4] The bridge was the only means of communication between the townships of Broughton and Pendleton[5] and a source of great local pride, as the Menai Suspension Bridge had opened only that year and suspension bridges were then considered the "new wonder of the age".[6]

Collapse

[edit]On 12 April 1831, the 60th Rifle Corps carried out an exercise on Kersal Moor under the command of Lieutenant Percy Slingsby Fitzgerald,[7] the son of John Fitzgerald, Member of Parliament and brother of the poet Edward FitzGerald. As a detachment of 74 men returned to barracks in Salford by way of the bridge,[8] the soldiers, who were marching four abreast, felt it begin to vibrate in time with their footsteps. Finding the vibration amusing, some of them started to whistle a marching tune, and to "humour it by the manner in which they stepped", causing the bridge to vibrate even more.[8] The head of the column had almost reached the Pendleton side when they heard "a sound resembling an irregular discharge of firearms".[8] Immediately, one of the iron columns supporting the suspension chains on the Broughton side of the river fell towards the bridge, carrying with it a large stone from the pier to which it had been bolted. The corner of the bridge, no longer supported, then fell 16 or 18 feet (4.9 or 5.5 m) into the river, throwing about forty of the soldiers into the water or against the chains. The river was low and the water only about two feet (60 cm) deep at that point. None of the men were killed, but twenty were injured, including six who suffered severe injuries including broken arms and legs, severe bruising, and contusions to the head.[8]

Cause

[edit]The subsequent investigation found that a bolt in one of the stay-chains had snapped, at the point where it was attached to the masonry of the ground anchor. The report criticised the construction method used, as the attachment to the ground anchor relied on a single bolt (rather than two), and the bolt was found to have been badly forged.[9] Several other bolts had bent but had not broken.[10] Three years previously, the engineer Eaton Hodgkinson had questioned the strength of the stay chains (compared to the suspension chains). Hodgkinson had argued that the chains should be rigorously tested, but they were not.[8] Before the accident one of the cross bolts had started to bend and crack, although it was believed[by whom?] to have been replaced by the time of the accident. The conclusion of the investigation was that the vibration caused by the marching precipitated the bolt's failure, but that it would have failed eventually anyway.[6]

Aftermath

[edit]

The collapse of the bridge caused something of a loss of confidence in suspension bridges, with one newspaper report at the time commenting:[8]

From what happened on this occasion we would greatly doubt the stability of the great Menai Bridge (admirable as its construction is), if a thousand men were to be marched across in close column, and keeping regular step. From its great length, the vibration would be tremendous before the head of the column had reached the further side, and some terrific calamity would be very likely to happen.

This did not stop the building of more suspension bridges, and the main consequence of the collapse was that the British Army issued the order to "break step" when soldiers were crossing a bridge.[6][11] French soldiers were also ordered to break step on bridges – nevertheless, marching was cited as a contributing factor to the collapse of the Angers Bridge in France during a storm in 1850, killing over 200 soldiers.[12]

Broughton Suspension Bridge was rebuilt and strengthened, but, according to the Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales (1870–72), it was propped temporarily whenever a large crowd was expected.[13] The suspension bridge was eventually replaced by a Pratt truss footbridge, designed by the Borough Engineer at a cost of about £2,300, which was formally opened on 2 April 1924.[14]

See also

[edit]- MythBusters' "Breakstep Bridge"

- MythBusters' "Myths revisited: Breakstep Bridge"

- Millennium Bridge, London – closed after two days due to excessive vibration, caused by pedestrians synchronising their steps

References

[edit]- ^ "Broughton Suspension Bridge". Dictionary of Scottish Architects. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- ^ Skempton, A. W.; Chrimes (2002). A biographical dictionary of civil engineers in Great Britain and Ireland. M (Illustrated ed.). Thomas Telford. ISBN 978-0-7277-2939-2.

- ^ Bishop, R.E.D. (1979). Vibration (Second ed.). Cambridge University Press, London.

- ^ Wilson, John Marius. "Descriptive Gazetteer Entry for Manchester". A vision of Britain through time. University of Portsmouth et al. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ Foy, T. Roby (5 January 1914). "Memories of old Broughton". Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser. British Newspaper Archive (subscription required). Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ a b c Smith, Alan (12 April 1975). "Broughton Bridge is falling down!". Manchester Evening News.

- ^ London Gazette Issue 18750 published on 26 November 1830. Page 4

- ^ a b c d e f Anon (16 April 1831). "Fall of the Broughton suspension bridge, near Manchester". The Manchester Guardian.

- ^ Taylor, Richard; Phillips, Richard (1831). The Philosophical Magazine: Or Annals of Chemistry, Mathematics, Astronomy, Natural History and General Science. Vol. ix. Richard Taylor. pp. 387, 388, 389.

- ^ Anon (1842). Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (ed.). Penny cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Vol. xxiii stearate-tagus. Charles Knight. pp. ss9.

- ^ Braun, Martin (1993). Differential Equations and Their Applications: An Introduction to Applied Mathematics (4 ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 175. ISBN 0-387-97894-1. Retrieved 30 May 2009.

- ^ Denenberg, David. "1839 Basse-Chaîne (Angers)". Bridgemeister.com. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- ^ Wilson, John Marius. "Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales (1870–72)". Genuki. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- ^ "New Irwell Bridge". The Manchester Guardian. 3 April 1924. p. 11.