Locrian mode

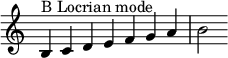

The Locrian mode is the seventh mode of the major scale. It is either a musical mode or simply a diatonic scale. On the piano, it is the scale that starts with B and only uses the white keys from there. Its ascending form consists of the key note, then: half step, whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, whole step.

History

[edit]Locrian is the word used to describe the inhabitants of the ancient Greek regions of Locris.[1] Although the term occurs in several classical authors on music theory, including Cleonides (as an octave species) and Athenaeus (as an obsolete harmonia), there is no warrant for the modern usage of Locrian as equivalent to Glarean's Hyperaeolian mode, in either classical, Renaissance, or later phases of modal theory through the 18th century, or modern scholarship on ancient Greek musical theory and practice.[2]

The name first came to be applied to modal chant theory after the 18th century,[3] when it was used to describe the mode newly-numbered as mode 11, with final on B, ambitus from that note to the octave above, and with semitones therefore between the first and second, and fourth and fifth degrees. Its reciting tone (or tenor) is G, its mediant D, and it has two participants: E and F.[4] The final, as its name implies, is the tone on which the chant eventually settles, and corresponds to the tonic in tonal music. The reciting tone is the tone around which the melody principally centres,[5] the mediant is named from its position between the final and reciting tone, and the participant is an auxiliary note, generally adjacent to the mediant in authentic modes and, in the plagal forms, coincident with the reciting tone of the corresponding authentic mode.[6]

Modern Locrian

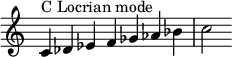

[edit]In modern practice, the Locrian may be considered to be a minor scale with the second and fifth scale degrees lowered a semitone. The Locrian mode may also be considered to be a scale beginning on the seventh scale degree of any Ionian, or major scale. The Locrian mode has the formula:

- 1, ♭2, ♭3, 4, ♭5, ♭6, ♭7

The chord progression for B locrian is Bdim, C, Dm, Em, F, G, Am. Its tonic chord is a diminished triad (Bdim in the Locrian mode of the diatonic scale corresponding to C major). This mode's diminished fifth and the Lydian mode's augmented fourth are the only modes of the major scale to have a tritone above the tonic.

Overview

[edit]The Locrian mode is the only modern diatonic mode in which the tonic triad is a diminished chord, which is considered dissonant. This is because the interval between the root and fifth of the chord is a diminished fifth. For example, the tonic triad of B Locrian is made from the notes B, D, F. The root is B and the fifth is F. The diminished-fifth interval between them is the cause for the chord's dissonance.[citation needed]

The name "Locrian" is borrowed from music theory of ancient Greece. However, what is now called the Locrian mode was what the Greeks called the Diatonic Mixolydian tonos. The Greeks used the term "Locrian" as an alternative name for their "Hypodorian", or "Common" tonos, with a scale running from mese to nete hyperbolaion, which in its diatonic genus corresponds to the modern Aeolian mode.[7] In his reform of modal theory in the Dodecachordon (1547), Heinrich Glarean named this division of the octave "Hyperaeolian" and printed some musical examples (a three-part polyphonic example specially commissioned from his friend Sixtus Dietrich, and the Christe from a mass by Pierre de La Rue), though he did not accept Hyperaeolian as one of his twelve modes.[8] The usage of the term "Locrian" as equivalent to Glarean's Hyperaeolian or the ancient Greek (diatonic) Mixolydian, however, has no authority before the 19th century.[9]

Usage

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2023) |

In practical terms it should be said that few rock songs that use modes such as the phrygian, Lydian, or locrian actually maintain a harmony rigorously fixed on them. What usually happens is that the scale is harmonized in [chords with perfect] fifths and the riffs are then played [over] those [chords]. ...[Slipknot's] track 'Everything Ends' uses an A locrian scale with the fourth note sometimes flattened.[10]

There are brief passages in works by Sergei Rachmaninoff (Prelude in B minor, op. 32, no. 10), Paul Hindemith (Ludus Tonalis), and Jean Sibelius (Symphony No. 4 in A minor, op. 63) that have been, or may be, regarded as being in the Locrian mode.[11] Claude Debussy's Jeux has three extended passages in the Locrian mode.[12] The theme of the second movement ("Turandot Scherzo") of Hindemith's Symphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria von Weber (1943) alternates sections in Mixolydian and Locrian modes, ending in Locrian.[13] "In Freezing Winter's Night", the ninth movement in Benjamin Britten's A Ceremony of Carols, is in Locrian mode.

English folk musician John Kirkpatrick's song "Dust to Dust" was written in the Locrian mode,[14] backed by his concertina. The Locrian mode is not at all traditional in English music, but was used by Kirkpatrick as a musical innovation.[15]

The song "Gliese 710" from King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard's 2022 album Ice, Death, Planets, Lungs, Mushrooms and Lava is in Locrian, following the album's theme of basing each song around one of the Greek modes.[16]

It is used in Middle Eastern music as Maqam Lami

References

[edit]- ^ "Locrian". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Harold S. Powers, "Locrian", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001); David Hiley, "Mode", The Oxford Companion to Music, edited by Alison Latham (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002) ISBN 978-0-19-866212-9 OCLC 59376677.

- ^ Harold S. Powers, "Locrian", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001)

- ^ W[illiam] S[myth] Rockstro, "Locrian Mode", A Dictionary of Music and Musicians (A.D. 1450–1880), by Eminent Writers, English and Foreign, vol. 2, edited by George Grove, D. C. L. (London: Macmillan and Co., 1880): 158.

- ^ Charlotte Smith, A Manual of Sixteenth-Century Contrapuntal Style (Newark: University of Delaware Press; London: Associated University Presses, 1989): 14. ISBN 978-0-87413-327-1.

- ^ W[illiam] S[myth] Rockstro "Modes, the Ecclesiastical", A Dictionary of Music and Musicians (A.D. 1450–1880), by Eminent Writers, English and Foreign, vol. 2, edited by George Grove, D. C. L., 340–43 (London: Macmillan and Co., 1880): 342.

- ^ Thomas J. Mathiesen, "Greece, §1: Ancient; 6: Music Theory". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001).

- ^ Harold S. Powers, "Hyperaeolian", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan, 2001.

- ^ Harold S. Powers, "Locrian", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001).

- ^ Rooksby, Rikky (2010). Riffs: How to Create and Play Great Guitar Riffs. Backbeat. ISBN 9781476855486.

- ^ Vincent Persichetti, Twentieth Century Harmony (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1961): 42.

- ^ Eduardo Larín, "'Waves' in Debussy's Jeux d'eau", Ex Tempore 12, no. 2 (Spring/Summer 2005).

- ^ Gene Anderson, "The Triumph of Timelessness over Time in Hindemith's 'Turandot Scherzo' from Symphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria von Weber", College Music Symposium 36 (1996): 1–15. Citation on 3.

- ^ Boden, Jon (21 April 2012). "Dust To Dust « A Folk Song A Day". Archived from the original on 3 October 2012.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, John (Summer 2000). "The Art of Writing Songs". English Dance & Song. 62 (2): 27. ISSN 0013-8231. EFDSS 55987. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Carys (2022-09-07). "King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard announce three albums dropping in October, share "Ice V": Stream". Consequence. Retrieved 2022-10-13.

Further reading

[edit]- Bárdos, Lajos. 1976. "Egy 'szomorú' hangnem: Kodály zenéje és a lokrikum". Magyar zene: Zenetudományi folyóirat 17, no. 4 (December): 339–87.

- Hewitt, Michael. 2013. Musical Scales of the World. The Note Tree. ISBN 978-0957547001.

- Nichols, Roger, and Richard Langham Smith. 1989. Claude Debussy, Pelléas et Mélisande. Cambridge Opera Handbooks. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31446-6

- Rahn, Jay. 1978. "Constructs for Modality, ca. 1300–1550". Canadian Association of University Schools of Music Journal / Association Canadienne des Écoles Universitaires de Musique Journal, 8, no. 2 (Fall): 5–39.

- Rowold, Helge. 1999. "'To achieve perfect clarity of expression, that is my aim': Zum Verhältnis von Tradition und Neuerung in Benjamin Britten's War Requiem". Die Musikforschung 52, no. 2 (April–June): 212–19.

- Smith, Richard Langham. 1992. "Pelléas et Mélisande". The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, 4 vols, edited by Stanley Sadie. London: Macmillan Press; New York: Grove's Dictionaries of Music. ISBN 0-333-48552-1 (UK) ISBN 0-935859-92-6 (US)

External links

[edit]- Locrian mode for guitar at GOSK.com