Ako Adjei

Ako Adjei | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister for Foreign Affairs | |

| In office May 1961 – August 1962 | |

| President | Kwame Nkrumah |

| Preceded by | New portfolio |

| Succeeded by | Kwame Nkrumah |

| Minister for External Affairs | |

| In office April 1959 – May 1961 | |

| Prime Minister | Kwame Nkrumah |

| Preceded by | Kojo Botsio |

| Succeeded by | Portfolio changed |

| Resident Minister to Guinea | |

| In office February 1959 – September 1959 | |

| Prime Minister | Kwame Nkrumah |

| Preceded by | Nathaniel Azarco Welbeck |

| Succeeded by | J. H. Allassani |

| Minister for Labour and Cooperatives | |

| In office 1958 – February 1959 | |

| Prime Minister | Kwame Nkrumah |

| Preceded by | Nathaniel Azarco Welbeck |

| Succeeded by | Nathaniel Azarco Welbeck |

| Minister for Justice | |

| In office August 1957 – 1958 | |

| Prime Minister | Kwame Nkrumah |

| Preceded by | New |

| Succeeded by | Kofi Asante Ofori-Atta (Minister for Justice and Local Government) |

| Minister for Interior and Justice | |

| In office 29 February 1956 – August 1957 | |

| Governor General | Charles Arden-Clarke |

| Prime Minister | Kwame Nkrumah |

| Preceded by | Archie Casely-Hayford (Minister for Interior) |

| Succeeded by | Krobo Edusei (Minister for Interior) |

| Minister for Trade and Labour | |

| In office 1954 – 29 February 1956 | |

| Governor General | Charles Arden-Clarke |

| Prime Minister | Kwame Nkrumah |

| Preceded by | New |

| Succeeded by | Edward Okyere Asafu-Adjaye |

| Member of the Ghana Parliament for Accra East | |

| In office 15 June 1954 – August 1962 | |

| Preceded by | New |

| Succeeded by | Ehi Wanyalolo Note Dowuona |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ebenezer Ako Adjei 17 June 1916 Adjeikrom, Akyem Abuakwa, Ghana |

| Died | 14 January 2002 (aged 85) Accra, Ghana |

| Political party | Convention People's Party |

| Other political affiliations | United Gold Coast Convention |

| Spouse | Theodosia Kotei-Amon |

| Children | 3 |

| Residence(s) | Accra, Ghana |

| Education | Accra Academy |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Signature | |

| One of "The Big Six" in Ghana's independence struggle | |

Ako Adjei (17 June 1916 – 14 January 2002),[1] was a Ghanaian statesman, politician, lawyer and journalist. He was a member of the United Gold Coast Convention and one of six leaders who were detained during Ghana's struggle for political independence from Britain, a group famously called The Big Six.[2][3] Adjei became a member of parliament as a Convention People's Party candidate in 1954 and held ministerial offices until 1962 when as Minister for Foreign Affairs he was wrongfully detained for the Kulungugu bomb attack.[4]

Born in Adjeikrom, a small village in the Akyem Abuakwa area, Ako Adjei had his tertiary education in the United States and the United Kingdom. After his studies abroad, he returned home to join the movement of Gold Coast's struggle for political independence by joining the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) as a founding member. Ako Adjei was instrumental in introducing Kwame Nkrumah into Ghana's political scene when he recommended him for the full time post of Organising Secretary of the UGCC.[5]

Following Ghana's Independence, Ako Adjei served in various political portfolios including being the first Minister for Interior and Justice for the newly born nation, Ghana. He also became Ghana's first Minister of Foreign Affairs when the portfolio was changed from Minister for External Affairs to Minister for Foreign Affairs in May 1961. Ako Adjei's political career was however precluded after his detention for allegedly plotting to assassinate the then president Kwame Nkrumah in the Kulungugu bomb attack in 1962.

After his release in 1966, Ako Adjei spent the rest of his life in relative obscurity. He remained unseen or unheard in the Ghanaian national and political discourse. He resolved to focus on his family and his career as a legal practitioner. In 1992 he published a biography of the Ghanaian businessman and statesman George Grant.[6] In 1997 he was awarded the Order of the Star of Ghana award – the highest national award of the Republic of Ghana, for his contribution to the struggle for Ghana's independence. Ako Adjei died after a short illness in 2002.[7]

Early life and education

[edit]Gold Coast

[edit]Ako Adjei was born on 17 June 1916 in Adjeikrom in Akyem Abuakwa land.[5] Adjeikrom is a small farming community found in the Eastern Region of Ghana (then the Gold Coast). His father was Samuel Adjei, a farmer and trader, whom Ako Adjei's place of birth is thought to be named after, and his mother was Johanna Okaile Adjei. Both parents were from La, a settlement near the coastal sea at Accra. He had many brothers and sisters but was the youngest of his father's children.[8][9]

His early education began in the Eastern Region at the Busoso Railway Primary School, where he walked 14 miles to school and back home. He was taken to Accra where he continued his education at the La Presbyterian Junior School starting in class 3. He was unable to speak the Ga language which was his mother tongue, however, he could read and write Twi, and speak Dangme. He continued in the La Presbyterian Senior School until 1933 when he got to Standard Six. In March 1933 he won a scholarship to study at Christ Church Grammar School, a private secondary school which was on the point of winding up. He returned to the La Presbyterian Senior School after a month at Christ Church Grammar School because he did not like the school.[9]

His father was then persuaded to send him to the Accra Academy, then a private secondary school trying to find its feet through the help of enterprising young men. In April 1933 he entered the Accra Academy and he liked it there. He walked four miles from La to Jamestown (where the school was then situated), because he could not afford the bus fare which was about two pence. In 1934 he sat for the Junior Cambridge examination and passed it. While at the Accra Academy, he found difficulty in meeting the cost of books, however, a member of the staff, Mr. Halm Addo (one of the four founders of the school), used to help him with money for books. In December, 1936 he was one of the candidates presented by the Accra Academy for the Cambridge Senior School leaving Certificate Examination. Among the candidates who passed the examination, only two obtained exemption from the London Matriculation Examination Board. One of these students was Ako Adjei.[9]

He taught for a while at the Accra Academy in 1937[10] before joining the Junior Civil Service in June 1937. From June 1937 to December 1938 he was a Second Division Clerk in the Gold Coast Civil Service. He was assigned to assist Harold Cooper, a European Assistant Colonial Secretary, and J. E. S. de Graft-Hayford to organise and establish the Gold Coast Broadcasting Service. These were the beginnings of what is now the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation.[9]

While studying at the Accra Academy Ako Adjei had taken an interest in journalism, he wrote for the African Morning Post, a newspaper that belonged to Nnamdi Azikiwe, who later became the first president of Nigeria. Azikiwe also took an interest in him and arranged for him to study at Lincoln University, Pennsylvania, United States. In November 1938, he resigned from the Civil Service and left for England in December that year.[9]

United States

[edit]In January 1939, he arrived at Lincoln University, Pennsylvania to the welcome of K. A. B. Jones-Quartey, a student from the Gold Coast whom Ako Adjei had known due to his work with the Accra Morning Post. Jones-Quartey had been accompanied to welcome him by another Gold Coast student who was introduced as Francis Nwia Kofi Nkrumah (Kwame Nkrumah). At Lincoln University he was housed at Houston Hall and played football (soccer) for the university. He registered for courses in Political Science, Economics, Sociology, English, Latin and Philosophy.[11]

Ako Adjei shared the same room at Houston Hall with Jones-Quartey and their room was opposite Nkrumah's room, which was larger in size due to Nkrumah being a postgraduate student. Ako Adjei formed a close relationship with Nkrumah despite the age gap that apparently existed between them. Together with a group of students, they often had long heated discussions (known as bull sessions) about the emancipation of African countries from colonial domination. Among the African students who regularly took part in these discussions were Jones-Quartey, Ozuomba Mbadiwe, Nwafor Orizu and Ikechukwu Ikejiani.[11]

After one and half years at Lincoln, he won a Phelps-Stokes Fund scholarship to attend Hampton Institute in Virginia, and transferred there to complete his university degree. He won another scholarship to the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and obtained a master's degree in June 1943. He gained employment as a lecturer at the African Studies Department at Fisk University through the assistance of Dr. Edwin W. Smith, a missionary. Dr. Smith had come from England to establish the new department and invited Ako Adjei to be his assistant at its founding.[11]

United Kingdom

[edit]Ako Adjei moved to the United Kingdom to pursue his childhood dream of becoming a lawyer. His teaching job at the Fisk University had provided him finances to enroll at the Inner Temple in early May 1944. Even though he had saved enough to begin the course he needed more money to complete it. His father leased a small family house located at the Post Office Lane in Accra to a Lebanese merchant for £10 a year for fifty (50) years and took thirty (30) years' rent in advance. His father died before the negotiations were completed so he and his brothers had to sign the papers before the sum of £300 was paid by the Lebanese merchant.[9]

In Britain, Ako Adjei took an active interest in colonial politics. Following the end of the Second World War, a number of British colonies in Asia had gained independence, this made colonial students from West Africa more concerned about the conditions at home and caused them to demand for the abolition of colonialism in West Africa.[9]

Ako Adjei played a prominent role in the West African Students Union (WASU) and became its president.[12][13] Nkrumah arrived in Britain in 1945, a few weeks after his arrival in London, Ako Adjei run into him during one of his rounds as the president of WASU. Nkrumah was then facing accommodation problems and he consequently hosted him at his No.25 Lauvier Road, until he found accommodation for him (Nkrumah) at No. 60 Burghley Road, near Tufnel Park Tube Station. Nkrumah was resident there until he left London in 1947. Ako Adjei then introduced Nkrumah to WASU and Kojo Botsio who later became Nkrumah's right-hand man. Recalling his WASU days, Ako Adjei recounted, "When Nkrumah arrived in London I was then President of the WASU. I took Nkrumah to the WASU Secretariat where I introduced him to Kankam Boadu and Joe Appiah, who were other members of the executive committee of WASU, and to Kojo Botsio who we had then engaged as warden of the student's Hostel, at No.l South Villas, Camden Town, London N. W. I. I must say that Nkrumah's arrival and active participation in the work of WASU invigorated the Union. It was against this background that we organised the Fifth Pan-African Congress which was held in Manchester in 1945 with George Padmore and Nkrumah as Joint Secretaries and myself as one of the active organisers."[8] This conference went on to be regarded as a turning point within the independence struggle and was attended by the likes of W. E. B. Du Bois, Hastings Banda and Jomo Kenyatta.[14]

Ako Adjei enrolled at the London School of Economics and Political Science for his M.Sc. degree programme while studying law at the Inner Temple. His topic for the dissertation, The Dynamics of Social Change was approved, however, the course, coupled with his political activities precluded his research due to time constraints.[8]

Ako Adjei passed all his Bar examinations and was called to the Bar at the Inner Temple in January 1947.[9][8]

Return to the Gold Coast

[edit]Ako Adjei returned to the Gold Coast in May 1947 and in June 1947, he enrolled at the Ghana bar. His initial intention was to set up a "chain of newspapers" to continue the agitation for self-rule, a course he had committed himself to while in London. He was however, unable to start the newspapers due to his financial circumstances then, he subsequently joined the Adumoa-Bossman and Co. chambers to practise as a private legal practitioner.[8][9]

United Gold Coast Convention

[edit]After staying in Accra for a couple of days, he visited J. B. Danquah who was then with others discussing the possibility of forming a national political movement and Ako Adjei joined in the discussions.[8] Ako Adjei like most Gold Coast students in Britain at the time was fed up with the British newspaper reportage that created the impression that the Gold Coast was the most loyal colony. Danquah assured him that a lot of work was being done to establish a national political front.[9]

Within four days of his arrival home he was taken by J. B. Danquah to a meeting of the Planning Committee of the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC).[9] He then became a member of the committee and on 4 August 1947 when the convention was inaugurated at Saltpond, he became one of the leading members. On 22 August 1947, the Accra branch of the convention was inaugurated and he was elected secretary with Edward Akufo-Addo as president and Emmanuel Obetsebi-Lamptey together with J. Quist-Therson as the vice-presidents. As membership of the convention grew, the leading members decided it was best to convert the movement to a political party. As a result, there was the need for a full-time secretary. J. B. Danquah suggested Ako Adjei, however, he declined the offer for reasons of running his African National Times newspaper and practising law alongside. He subsequently suggested Kwame Nkrumah who was then running the West African National Secretariat (WANS) at 94 Grays' Inn, London.[8]

According to Ako Adjei he recommended Kwame Nkrumah because he had grown to know his organisational capabilities and that he knew he will be interested in the job. This was because, before he left London for Accra Nkrumah had told him:

"Ako you're going ahead of me. When you get to the Gold Coast and there is a job which you think I can do, let me know right away so that I would come and work for sometime; save some money and then return to London to complete my studies in law at Gray 's Inn."

This was a promise he had made thus when he heard of the full time general-secretary job he did not hesitate to recommend him. The convention accepted his suggestion and he wrote to Nkrumah about it and later sent him £100 which was provided by George Alfred Grant, the founder, president and financier of the UGCC for his trip to the Gold Coast. Upon the arrival of Nkrumah, Ako Adjei introduced him to the leading members of the party: "He arrived in December 1947 and I introduced him to G. A. Grant, J. B. Danquah, R. S. Blay and other members of the UGCC."[8]

The Big Six

[edit]When Nkrumah assumed office as general-secretary of the UGCC he began initiating moves to expand the convention colony-wide and increase its membership.[8] The leading members of the UGCC had also taken particular interest in the plight of the ex-servicemen who had not received their emoluments after the Second World War.[15] They were invited by the world war veterans for their war veterans' meetings and at various times been made guest speakers.[15]

Due to the goodwill and rapport built between the two parties, the lawyers among the politicians of the UGCC helped the ex-servicemen draft their petition to the governor.[15] The presentation of the petition on 24 February 1948 led to crossroad shooting which at the time had coincided with the Nii Kwabena Bonnie III (Osu Alata Mantse) led boycott campaign resulting in the 1948 Accra Riots.[8]

Ako Adjei and other leading members of the UGCC namely J. B. Danquah, Emmanuel Obetsebi-Lamptey, Edward Akufo-Addo, William Ofori Atta and Kwame Nkrumah, who were later famously referred to as the Big Six were consequently arrested and blamed by the then British government for the unrest in the colony and Ako Adjei was detained at Navrongo.[8] The release of the Big Six saw a separation between Nkrumah and the other members of the UGCC and Nkrumah eventually broke away in 1949 to found the Convention People's Party (CPP). Ako Adjei however stayed with the UGCC and subsequently became critical of Nkrumah in his newspapers, the African National Times and the Star of Ghana.[8]

1951 election and the Ghana Congress Party

[edit]During the 1951 Gold Coast legislative election, Ako Adjei stood on the ticket of the UGCC to represent the Accra Central Municipal Electoral District in the Gold Coast Legislative Assembly. He polled 1,451 votes as against Nkrumah's (CPP) 20,780, T. Hutton Mills' (CPP) 19,812, and Emmanuel Obetsebi Lamptey's (UGCC) 1,630 votes.[8] Following the poor showing of the UGCC in the elections, he joined others to urge for a merger of the opposition parties. He became the Secretary of the Ghana Congress Party (GCP) when it was formed in May 1952. After sometime with the GCP, Ako Adjei refused to attend meetings as constant criticisms were levelled against him for introducing Nkrumah to dismantle the UGCC.[8][16]

Convention People's Party

[edit]In March 1953, Ako Adjei succumbed to pressure from friends such as E. C. Quaye, Sonny Provençal and Paul Tagoe, and agreed to join the Convention People's Party. In early March 1953 he was introduced in a huge rally at Arena, Accra where he delivered his first speech on the platform as a member of the CPP.[8]

During the 1954 Gold Coast legislative election, he stood on the ticket of the CPP to represent Accra East in the Gold Coast Legislative Assembly. He polled 11,660 votes against Nai Tete's 768, Kwamla Armah-Kwarteng's 471, and Nii Kwabena Bonnie III's 317 votes.[8] He entered parliament on 15 June 1954.

Following his record at the polls during the 1954 election, Ako Adjei was made a member of the Gold Coast cabinet on 28 July 1954 by Nkrumah, who was then prime minister and head of government business. He was appointed Minister of Trade and Labour.[17] One of the reasons for his appointment was the fact that he belonged to a class under-represented in the CPP, he being an intellectual and professional in the middle class, the move was regarded as a strategy to pull people of his status to the CPP. As Minister of Trade and Labour, he was responsible for many aspects of the country's life, he oversaw the Agricultural Produce Marketing Board, the Cocoa Marketing Board, the Industrial Development Corporation, Trade Unions and Cooperatives.[8]

On 29 February 1956, he was appointed Minister for Interior and Justice, a position that was initially held by Archie Casely-Hayford. That same year, he was re-elected in the 1956 Gold Coast legislative election to represent the Accra East district electoral area in the Gold Coast Legislative Assembly.[citation needed]

Post Ghanaian independence

[edit]Minister for Interior and Justice

[edit]

Standing (L to R): J. H. Allassani, N.A. Welbeck, Kofi Asante Ofori-Atta, Ako Adjei, J.E. Jantuah, Imoru Egala

Sitting (L to R): A. Casely-Hayford, Kojo Botsio, Kwame Nkrumah, Komla Agbeli Gbedemah, E.O. Asafu-Adjaye

Following Ghana's independence on 6 March 1957, major appointments were made at cabinet level by the then Prime Minister Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, Ako Adjei was however, maintained as Minister for Interior and Justice,[18] a portfolio that was separated about six months later. In August 1957, the Ministry of Interior and Justice was separated into the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Justice. The Ministry of Interior was headed by Krobo Edusei while Ako Adjei was made Minister of Justice.[19] It was rumoured then that this move was made by Nkrumah, the then prime minister, because Ako Adjei though a Ga himself was seen as "too gentlemanly" to deal with the problems created by the Ga-Adangbe Shifimo Kpee (a tribal organisation), which had been inaugurated not long ago in Accra.[20]

Others remained positive about his new appointment believing he was in a better position to deal better with matters affecting Ghana's judiciary as a trained lawyer. As Minister for Justice, he was responsible for the functions of the Land Boundaries Settlement Commission, financial and ministerial matters with relation to the Supreme Court, local court and Customary Law, and foreign processes.[19]

Minister for Labour and Cooperatives

[edit]A year later, Ako Adjei was moved to the Ministry of Labour and Cooperatives.[21] As Minister of Labour and Cooperatives, he aided the labour movement of Ghana in forming new structures that have persisted till this today. While serving in this capacity he often led the Ghanaian delegations to the United Nations.[22]

Resident Minister in Guinea and Minister for Foreign Affairs

[edit]In February 1959, Ako Adjei replaced Nathaniel Azarco Welbeck as the Resident Minister of Guinea. While serving as Ghana's chief representative in Guinea, he was appointed Minister of External Affairs in April that year.[23] He occupied both positions as Ghana's resident minister in Guinea and Ghana's Minister of External Affairs until September 1959 when he was relieved of his duties in Guinea.[23] He was replaced by J. H. Allassani as Resident Minister of Guinea.[24]

On 8 April 1961, Ako Adjei was in New York City when Nkrumah the then president of Ghana announced in a dawn broadcast that he had removed African Affairs from the jurisdiction of the Ministry of External Affairs thereby appointing Imoru Egala as the Minister of State for African Affairs, a position Egala held for a brief period of time with no successor.[25] Ako Adjei returned to Ghana without permission to plead his course for a more coordinated foreign policy. He believed that the goal of African unity would be unrealistic if African relations were detached from his ministry.[25] His efforts, however, to revert the president's decision proved futile.[25]

In May 1961 the portfolio of the Minister of External Affairs was consequently changed to the Minister of Foreign Affairs.[23] Ako Adjei thus became Ghana's first Minister of Foreign Affairs in the first republic.[26] As Ghana's first foreign minister, he played a prominent role in formulating the country's foreign policy and level of international engagements. According to Sheikh I. C. Quaye, he "assisted to lay the foundations of our international relations at the height of the cold war when the country needed to walk the diplomatic tight rope unflinchingly".[27] Kwesi Armah reflecting on Ako Adjei's time in office said he "presented a very sober image of Ghana and powerfully presented Ghana's stand to the UN and other international conferences."[28]

As the Minister of Foreign Affairs, he announced a complete boycott of South African goods, ships and airlines into the country, he also maintained that South Africans will only be allowed in the country if they declared opposition to apartheid.[29] During his tenure in the Ministry, Ako Adjei called for "a Union of African States, to provide the framework within which any plans for economic, social and cultural cooperation can in fact, operate to the best advantage of all."[30]

During a meeting of African Foreign Ministers in Addis Ababa in June 1960, he proposed the concept of a "complete political union" for Africa and pushed for the establishment of Africa Customs Union, Africa Free Trade Zone, and Africa Development Fund; policies that were along the lines of these proposals were adopted by the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) which was birthed while he was in prison in 1963 and the Africa Union (AU) which succeeded the OAU in 2001.[5]

Ako Adjei remained in charge of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs until August 1962 when he was charged with treason in relation to the Kulungugu bomb attack, a failed assassination attempt on the then president, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah's life on 1 August 1962. Nkrumah replaced him by assuming the portfolio of the Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1962.[31]

Treason trial and detention

[edit]

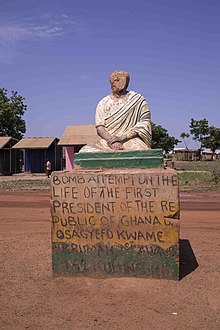

Kwame Nkrumah travelled to Tenkodogo on 31 July 1962 to have a meeting with Maurice Yameogo the president of Upper Volta now Burkina Faso. The meeting was to discuss further plans to eliminate customs barriers between Ghana and the Upper Volta. A move that was seen as a small step towards Pan-African unity. An unusually heavy downpour complicated the return trip from Tenkodogo on 1 August 1962, causing the usual order of the convoy to be in disarray over the poor road that connected the two countries. A bomb was reportedly thrown at the president in Kulungugu, a town in the Upper Region of Ghana when he was forced to stop to receive a bouquet from a young boy.[5]

Ako Adjei, then Minister of Foreign Affairs, together with Tawia Adamafio, then Minister of Information, Hugh Horatio Cofie Crabbe, then CPP Executive Secretary, Joseph Yaw Manu, a civil servant and alleged member of the United Party (UP) and Robert Benjamin Otchere, former UP member of parliament, were accused of plotting to assassinate the president.[5]

Ako Adjei, Tawiah Adamafio and Cofie Crabbe were tried and acquitted by the Supreme Court on the basis that the evidence presented against them was rather circumstantial and fraudulent, and centred more on the dissensions in the Convention People's Party (CPP) as the basis of their accusation.[5] A member of the Ghana Parliament described their guilt as such:

On the journey... to the place of the incident, they (Adamafio, Crabbe, and Ako Adjei), isolated themselves from the Leader, to whom they had clung previously all along as if they were his lovers. They rode in different cars and were hundreds of yards away leaving the President behind.

— F. E. Techie Menson in a speech to Parliament on 6 September 1962.[5]

A retrial was said to have been necessitated by the evidence of a fetish priest who also accused the three of conniving to kill the president.[5]

The three judges who had acquitted the three men – Justice Sir. Kobina Arku Korsah, Justice Edward Akufo-Addo (a Big Six) and Justice Kofi Adumua Bossman – were subsequently forced to resign. Two other judges, William Bedford Van Lare and Robert Samuel Blay (a founding member of the United Gold Coast Convention) were dismissed for protesting the dismissal of the three judges. Nkrumah then empaneled a 12-man jury headed by Justice Julius Sarkodee-Addo,[32] who found the acquitted, guilty based largely on the evidence of the fetish priest. Ako Adjei and the two others were consequently sentenced to death, however, the sentence was commuted by the president to a life imprisonment sentence and later, a 20-year imprisonment sentence in an address to parliament on 26 March 1965.[5][8][32]

Ako Adjei reflecting on the event of 1 August 1962 had this to say:

"I was innocent and I know that my two friends, Tawia Adamafio and Cofie Crabbe were also innocent. What happened was that I accompanied Nkrumah in my capacity as Foreign Minister to a miniature summit between President Nkrumah and President Yameogo at Tenkudugu at the northern boundary between Togo, Ghana and Upper Volta on July 31, 1962. On our return journey, I was in the President's party which made an unscheduled stop at a small school at Kulungugu. Within minutes after the President alighted and received a bouquet from a young school boy, a hand grenade was thrown at him. The innocent boy received a direct hit and was killed instantly. Fortunately, the hand grenade missed the President although some pellets found their way to his back. We got the Osagyefo to Bawku where he was later sent to Tamale. Back in Accra everything moved on smoothly. And in the latter part of July 1962 I received a note from Dr. Okechuku Ekejeani, a former colleague at Lincoln University and a mutual friend of Nkrumah and myself. He was travelling from London and sent a cablegram on board his ship to the President and myself. When I showed my cable to Nkrumah, he told me to go for him and send him to my house and entertain him on his behalf. I was to bring him the following day to the Flagstaff House for another reception before he left for Lagos in the afternoon. We were entertaining him on that Wednesday, August 29, 1962 when I was arrested and taken away. For the next four years only God knew what happened to me."[8]

Ako Adjei together with his three colleagues were among many political prisoners that were released by the National Liberation Council after the overthrow of president Nkrumah and the First Republican Government on 24 February 1966. He was released from his detention in the Nsawam Medium Security Prison on 6 September 1966 by an amnesty from the National Liberation Council.[5][8]

Later life

[edit]On the eve of his release from the Nsawam Prison in 1966, Ako Adjei completely forswore politics after the whole experience; what he believed to have been a false accusation and the prison term. After his release, he devoted himself to his family and his legal life.[8]

He gave much attention to his wife and children. According to him, his wife and children were very supportive during the period when he was trialled, retrialled and subsequently imprisoned.[8]

He reorganised his professional life, succeeded in reorganising his chambers, Teianshi Chambers, and resumed private practice as a legal practitioner.[8]

Following the second military coup in Ghana, Ako-Adjei was made a member of the commission by the Supreme Military Council in 1978 to draft a constitution for the Third Republic of Ghana. According to The Ghanaian Chronicle, the last time Ako Adjei was seen in any high-profile gathering was in the senior citizens get together organised by the ex-President Rawlings during the latter period of his tenure as president. Due to his condition at the time, his relatives denied reporters an opportunity to interview him.[33]

Death and state burial

[edit]Ako Adjei was the last member of the famous Big Six to die. After a short illness, he died on 14 January 2002 at the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, at the age of 85 years. He was survived by his wife and four children.[5]

His death drew tributes from statesmen including the then president of Ghana, John Agyekum Kufour who declared that he will be given a State burial.[5][34] He said "the nation owes Dr. Ako-Adjei gratitude as a hero, who served the country as a young man, for democratic rule in future. As one of the Big Six in Ghana's political history, the death of Dr. Ako-Adjei marks the end of the first cycle of history in terms of the harsh political atmosphere in the country at that time. But the memory of that era cannot be erased". He also added that "They launched a political party system of which the government is a beneficiary. Ghanaians benefiting from this great legacy and achievement owe it a duty to rally behind the bereaved family to offer Dr. Ako-Adjei a fitting state burial".[34]

The then Attorney General and Minister for Justice and current president of Ghana, Nana Akufo-Addo paying tribute said; "the death of Dr. Ako-Adjei has marked the end of the era of the founding fathers of the nation and Ghanaians are now left on their own to survive." He added that "the vision that energised them to ensure free democratic rule now prevailes in the country, they did a great deal of work for our country and he is one of the heroes of this country".[34]

While the late Jake Obetsebi-Lamptey, the then Minister for Information also had this to say: "the chapter on the era of the Big Six has not been erased with the death of Dr. Ako-Adjei because their experiences are available for future generations. There were a lot of other Ghanaians with the Big Six, who championed the cause of democracy. If you do your best for your country, you would be remembered."[34]

State burial

[edit]On the day of his burial, all flags flew at half-mast in his honour.[34] The state funeral service was held at the forecourt of the state house. Present at the ceremony were politicians, parliamentarians, ministers of state, members of the Council of State, the diplomatic corps, chiefs, relatives, friends and sympathisers.[33]

A wreath was laid by the then president, Kufour on behalf of the government and people of Ghana, Mr. Hackman Owusu-Agyeman, then Minister for Foreign Affairs laid another on behalf of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mr. Paul Adu-Gyamfi, who was then president of the Ghana Bar Association laid the third wreath on behalf of the association while a family member laid the fourth wreath on behalf of the bereaved family.[33]

Joseph Henry Mensah, then the Senior Minister, read the government's tribute, saying:

"Dr. Ako Adjei was among those who articulated the dream of African unity and political agitation in the country. After the break away of the Convention Peoples' Party (CPP) from the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), Dr. Ako-Adjei became the bridge between the two political groupings. Ghana has lost a gem because it could not benefit from his experiences and undoubted wisdom. When we learn from his life we resolve never again to have a person of his stature to suffer his fate."[33]

Following the State burial, a private burial was held at the mausoleum of the Holy Trinity Church of God, Okoman, Dome, in Accra.[35]

Personal life

[edit]Ako Adjei was married to Theodosia Ako Adjei (née Kote-Amon) and together they had four daughters. He was a Christian and a member of the Presbyterian Church of Ghana. As a Christian, he believed and emphasised as his philosophy of life that God controlled all affairs and had a purpose for everybody on earth. "What every individual must do therefore is to allow God to use him as a tool to serve Him."[8]

Honours

[edit]- In 1946, he was made a member of the Royal Institute of International Affairs[36]

- In 1952 he was made a member of the American Academy of Political and Social Science[36]

- In 1962 he was awarded with an Honorary degree of Doctor of Laws from his alma mater, Lincoln University, Pennsylvania, United States[37]

- On 7 March 1997 as part of Ghana's 40th Independence Day anniversary celebrations, Ako Adjei was awarded Officer of the Order of the Star of Ghana – the highest national honour of the Republic of Ghana by the then president Jerry John Rawlings for his "contribution to the struggle for Ghana's independence" [5]

- In 1999, he was given the Millennium Excellence Award for Outstanding Statesmen.[27]

Legacy

[edit]The Ako Adjei Interchange in Accra, which used to be Sankara Interchange, was renamed after him.[38][39] There is also an Ako-Adjei Park in Osu, Accra.

Quotes

[edit]"Ghana is our country. We have nowhere to go. This is where God has placed us and the earlier we realized this the better for all of us."[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Duodu, Cameron (March 2002). "Ako Adjei--the Walking History of Ghana:Cameron Duodu on One of the Founding Fathers of Ghanaian Independence Who Died in Accra on 14 January". New African. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ "Big six enduring lessons from the founding fathers of Ghana". GhanaWeb. 6 August 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Afful, Aba (16 October 2019). "Meet Dr. Ako-Adjei the only Big Six member who lived through 9 governments". Yen.com.gh - Ghana news. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Ghana pays tribute to founders' - Graphic Online". graphic ghana. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Ellison, Kofi (22 February 2002). "Dr. Ebenezer Ako Adjei - An Appreciation". Ghana Web. Ghana Home Page. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ Adjei, Ako (1992). Life and work of George Alfred Grant (Paa Grant). Accra: Waterville Pub. House. ISBN 978-9964-5-0233-1. OCLC 32650474.

- ^ "Big Six Enduring Lessons From The Founding Fathers Of Ghana". Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Vieta, Kojo T. (1999). The Flagbearers of Ghana:Profiles of One Hundred Distinguished Ghanaians. Ena Publications. p. 56. ISBN 9789988001384.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ofosu-Appiah, L H (1974). The life and times of Dr. J. B. Danquah. Waterville Pub. House. p. 64.

- ^ Segal, Ronald (1961). Political Africa:A Who's who of Personalities and Parties. Praeger. p. 7.

- ^ a b c Chinebuah, Aidoohene Blay (2017). Ghana's Pride and Glory:Biography of Some Eminent Ghanaian Personalities and Sir Gordon Guggisberg. Graphic Communications. p. 218.

- ^ "Dr. Ako Adjei-Founder member of UGCC". ghanaculture.gov.gh. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Six Lessons From Ghana's Big Six". newsghana.com.gh. July 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ Adi, Hakim; Sherwood, Marika (1995). The 1945 Manchester Pan-African Congress Revisited. New Beacon Books. ISBN 978-1-873201-12-1.

- ^ a b c "The Contribution Of The Veteran Towards Independence". News Ghana. 28 February 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Botwe-Asamoah, Kwame (17 June 2013). Kwame Nkrumah's Politico-Cultural Thought and Politics:An African-Centered Paradigm for the Second Phase of the African Revolution. Routledge. p. 98. ISBN 9780415948333.

- ^ Ministry of Trade and Labour (1955). Gold Coast, Handbook on Trade and Commerce. p. 3.

- ^ Rathbone, Richard (2000). Nkrumah & the Chiefs: The Politics of Chieftaincy in Ghana, 1951-60. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 9780821413067.

- ^ a b Nkrumah, Kwame (1957). Ghana's Policy at Home and Abroad:Text of Speech Given in the Ghana Parliament, 29 August 1957, by Kwame Nkrumah, Prime Minister. Information Office, Embassy of Ghana. p. 13.

- ^ "New Commonwealth, Volume 38". Tothill Press. 1960. p. 3.

- ^ "Ghana Today, Volumes 1-2". Information Section, Ghana Office. 1957. p. 11.

- ^ "Ghana Today, Volumes 1-2". Information Section, Ghana Office. 1957. p. 2.

- ^ a b c Grilli, Matteo (6 August 2018). Nkrumaism and African Nationalism:Ghana's Pan-African Foreign Policy in the Age of Decolonization. Springer. p. 112. ISBN 9783319913254.

- ^ Thompson, W. S. (1969). Ghana's Foreign Policy, 1957-1966: Diplomacy Ideology, and the New State. Princeton University Press. p. 75. ISBN 9781400876303.

- ^ a b c Thompson, W. S. (1969). Ghana's Foreign Policy, 1957-1966: Diplomacy Ideology, and the New State. Princeton University Press. p. 199. ISBN 9781400876303.

- ^ Ebenezer, Ako Adjei (1992). Life and work of George Alfred Grant (Paa Grant). Waterville Publishing House. p. 34. ISBN 9789964502331.

- ^ a b "Sankara Interchange re-named after Dr. Ako Adjei". Modern Ghana. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ Armah, Kwesi (2004). Peace Without Power: Ghana's Foreign Policy, 1957-1966. p. 20.

- ^ Asamoah, Obed (2014). The Political History of Ghana (1950-2013): The Experience of a Non-Conformist. AuthorHouse. p. 106. ISBN 9781496985637.

- ^ Akinyemi, A. Bolaji (1974). Foreign Policy and Federalism: The Nigerian Experience. p. 160.

- ^ Asamoah, Obed (2014). The Political History of Ghana (1950-2013): The Experience of a Non-Conformist. AuthorHouse. p. 57. ISBN 9781496985637.

- ^ a b Asamoah, Obed (2014). The Political History of Ghana (1950-2013): The Experience of a Non-Conformist. AuthorHouse. p. 55. ISBN 9781496985637.

- ^ a b c d "Ako Adjei Laid to Rest". Ghana Web. 24 February 2002. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Dr Ako-Adjei would be given state burial - JAK". Ghanaweb. 18 January 2002. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Ghana: Ako Adjei Laid to Rest". AllAfrica. 30 November 2001. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Ghana Year Book 1959". Ghana Year Book. Graphic Corporation: 143. 1959.

- ^ "Ako-Adjei, Ebenezer". Biographies. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ "Sankara Interchange re-named after Dr. Ako Adjei". Modern Ghana. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "Sankara Overpass Renamed After Ako Adjei". Modern Ghana. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

External links

[edit]- Ghana Home Page, ghanaweb.com

- Biography, s9.com

- Profile, kokorokoo.com via archive.org

- 1916 births

- 2002 deaths

- Ga-Adangbe people

- Alumni of the Accra Academy

- Alumni of the London School of Economics

- Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism alumni

- Foreign ministers of Ghana

- Ghanaian MPs 1951–1954

- Ghanaian MPs 1954–1956

- Ghanaian MPs 1956–1965

- Ghanaian MPs 1965–1966

- Hampton University alumni

- Interior ministers of Ghana

- Justice ministers of Ghana

- Lincoln University (Pennsylvania) alumni

- United Gold Coast Convention politicians

- Convention People's Party (Ghana) politicians

- Recipients of the Order of the Star of Ghana

- Ghanaian Christians

- 20th-century Ghanaian lawyers

- Ghanaian independence activists

- Ghanaian pan-Africanists