Mechouar

Mechouar or meshwar (Arabic: مشور, romanized: mashwar, meshwar; Spanish: mexuar; French: méchouar) is a type of location, typically a courtyard within a palace or a public square at the entrance of a palace, in the Maghreb (western North Africa) or in historic al-Andalus (Muslim Spain and Portugal). It can serve various functions such as a place of assembly or consultation (Arabic: michawara), an administrative area where the government's affairs are managed. It was the place where the sultan historically held audiences, receptions and ceremonies.[1][2][3] The name is sometimes also given to a larger area encompassing the palace, such as the citadel or royal district of a city.[4][5]

History

[edit]

An official public square or ceremonial space often existed in front of the main entrance or gate of early royal palaces in al-Andalus and North Africa, though the term meshwar was not necessarily used to designate them in historical sources. Notable examples include the square in front of the Bab al-Sudda gate of the Umayyad Palaces (8th-10th centuries) of Cordoba, Spain, where public executions took place and where the caliph would stand or sit on a viewing platform built above the palace gate,[6][7][2] as well as the ceremonial Bayn al-Qasrayn square in front of the Golden Gate (Bab al-Dhahab) of the Fatimid Palaces in Cairo, Egypt, where the Fatimid caliph also had a balcony above the gate from which to watch ceremonies below.[8][9] A similar square or open space also existed at the entrance of the palace-city of Madinat al-Zahra (10th century), at the end of the road that led to it from nearby Cordoba.[2]: 76 A couple of centuries later a main public square, known as the asaraq, was also included within the Kasbah of Marrakesh built by the Almohads at the end of the 12th century. It was situated within the administrative and service section of the citadel but it also gave access to the entrance of the sultan's private palaces.[10]

The term meshwar is later used to refer to reception areas or council chambers in the palaces of the region during the 13th-14th centuries and later. A meshwar was part of the citadel of al-Mansourah built by the Marinids in the 14th century just outside Tlemcen, Algeria, for example.[4] Before this, also in Tlemcen, the Zayyanids created a royal citadel known as the Qal'at al-Mashwar ("Citadel of the Mechouar"), still known today as the El Mechouar Palace. It was located on an earlier Almohad fortress and acted as the royal residence and center of power in the city in many periods.[2]: 223

A meshwar section (known as the Mexuar in Spanish) was also part of the Nasrid Palaces in the Alhambra of Granada, Spain. It was composed of a main external entrance gate followed by two consecutive courtyards leading to a council chamber at its eastern end, all of which was separate from the emir's palaces (the Comares Palace the Court of the Lions) further east. A number of other chambers were arranged around the courtyards, with the first courtyard likely being used by the secretaries and officials of the state administration, including the chancery or diwan, while the second courtyard was used by the emir for official audiences. The first courtyard even had its own mosque.[2]: 269–272

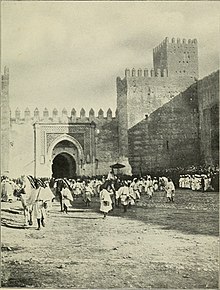

Mechouars are later found as a standard feature of most royal palaces (usually known as the dar al-makhzen) in Morocco, many now dating from the later Alaouite period (17th-20th centuries). These were generally large open squares located just outside the gates of the palace or occupying a space between the palace's main external entrance and the inner palaces of the sultan's private residence. They were used as reception areas, public squares for military parades, and places where the sultan or the qa'id (main judicial official of the city) would receive petitions.[11][10][2][12] Some inner mechouars, located within the palace enclosures, were used as the administrative section of the palace where various state officials worked or received their own audiences.[12][13] Examples of such mechouars include the multiple mechouars of the Dar al-Makhzen in Fez,[13] the mechouars along the south side of the Dar al-Makhzen and Kasbah of Marrakesh,[10] the Lalla Aouda Square of the Kasbah of Moulay Ismail (and also to an extent the nearby El-Hedim Square) in Meknes,[14][15] and the Mechouar of the Kasbah of Tangier, among others.[16] The modern Royal Palace of Rabat also includes a vast esplanade called the Mechouar, and the name is sometimes applied to the whole palace district in general.[17][18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Abadie, Louis (1994-01-01). Tlemcen, au passé retrouvé (in French). Editions J. Gandini. ISBN 9782906431027.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Arnold, Felix (2017). Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190624552.

- ^ Harrell, Richard S.; Sobelman, Harvey, eds. (2004). A Dictionary of Moroccan Arabic. Georgetown University Press. p. 88. ISBN 9781589011038.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bel, A.; Yalaoui, M. (2012). "Tilimsān". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill.

- ^ M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Architecture". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques. pp. 153–154.

- ^ "The andalusi Alcazar". ArqueoCordoba. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- ^ Brett, Michael (2017). The Fatimid Empire. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ Raymond, André. 1993. Le Caire. Fayard.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Deverdun, Gaston (1959). Marrakech: Des origines à 1912. Rabat: Éditions Techniques Nord-Africaines.

- ^ Bressolette, Henri (2016). A la découverte de Fès. L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2343090221.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Buret, M. (2012). "Mak̲h̲zan". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bressolette, Henri; Delaroziere, Jean (1983). "Fès-Jdid de sa fondation en 1276 au milieu du XXe siècle". Hespéris-Tamuda: 245–318.

- ^ El Khammar, Abdeltif (2017). "La mosquée de Lālla ʿAwda à Meknès: Histoire, architecture et mobilier en bois". Hespéris-Tamuda. LII (3): 255–275.

- ^ "Qasaba of Mawlāy Ismā'īl". www.qantara-med.org. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- ^ "Qasba Tanja". Archnet. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Rabat". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ "Dar al Makhzen – Palais Royal de Rabat" (in French). Retrieved 2020-10-26.