River

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually a freshwater stream, flowing on the Earth's land surface or inside caves towards another waterbody at a lower elevation, such as an ocean, sea, bay, lake, wetland, or another river. In some cases, a river flows into the ground or becomes dry at the end of its course without reaching another body of water. Small rivers can be referred to by names such as creek, brook, and rivulet. There are no official definitions for these various generic terms for a watercourse as applied to geographic features,[1] although in some countries or communities, a stream is customarily referred to by one of these names as determined by its size. Many names for small rivers are specific to geographic location; examples are "run" in some parts of the United States, "burn" in Scotland and Northeast England, and "beck" in Northern England. Sometimes a river is defined as being larger than a creek,[2] but not always; in English the language is vague compared to some languages like French, where a fleuve flows into the sea and a rivière is a tributary of another rivière or fleuve.[1]

Rivers are an important part of the water cycle. Water from a drainage basin generally collects into a river through surface runoff from precipitation, meltwater released from natural ice and snowpacks, and other underground sources such as groundwater recharge and springs. Rivers are often considered major features within a landscape; however, they actually only cover around 0.1% of the land on Earth. Rivers are also an important natural terraformer, as the erosive action of running water carves out rills, gullies, and valleys in the surface as well as transferring silt and dissolved minerals downstream, forming river deltas and islands where the flow slows down. As a waterbody, rivers also serve crucial ecological functions by providing and feeding freshwater habitats for aquatic and semiaquatic fauna and flora, especially for migratory fish species, as well as enabling terrestrial ecosystems to thrive in the riparian zones.

Rivers are significant to humankind since many human settlements and civilizations are built around sizeable rivers and streams.[3] Most of the major cities of the world are situated on the banks of rivers, as they are (or were) depended upon as a vital source of drinking water, for food supply via fishing and agricultural irrigation, for shipping, as natural borders and/or defensive terrains, as a source of hydropower to drive machinery or generate electricity, for bathing, and as a means of disposing of waste. In the pre-industrial era, larger rivers were a major obstacle to the movement of people, goods, and armies across regions. Towns often developed at the few locations suitable for fording, building bridges, or supporting ports; many major cities, such as London, are located at the narrowest and most reliable sites at which a river could be crossed via bridges or ferries.[4]

In Earth science disciplines, potamology is the scientific study of rivers, while limnology is the study of inland waters in general.

Topography

Source and drainage basin

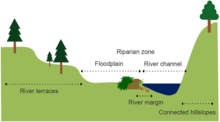

A river begins at a source (or more often several sources) which is usually a watershed, drains all the streams in its drainage basin, follows a watercourse, and ends at a terminus, either at a confluence or a mouth or mouths, which could form a river delta. The water in a river is usually confined to a channel, made up of a stream bed between banks. In larger rivers, there is often also a wider floodplain shaped by floodwaters over-topping the channel. Floodplains may be very wide in relation to the size of the river channel. This distinction between river channel and floodplain can be blurred, especially in urban areas where the floodplain of a river channel can become greatly developed by housing and industry.

The terms "upriver" and "downriver" refer to the direction towards the source of the river and towards the mouth of the river, respectively.

Channels

Rivers can flow down mountains and hills through valleys and can create canyons or gorges, especially when traversing plains. The river channel typically contains a single stream, but some rivers flow as several interconnecting streams, producing a braided river,[5] which occur on peneplains and some of the larger river deltas. Anastamosing rivers are similar to braided rivers and are quite rare; they have multiple sinuous channel – one carrying large volumes of sediment. There are rare cases of river bifurcation in which a river divides into distributaries, and the resultant flows end in different seas. An example is the Nerodime River in Kosovo.

A river flowing in its channel is a source of energy that acts on the river channel to change its shape and form. In 1757, German hydrologist Albert Brahms empirically observed that the submerged weight of objects that may be carried away by a river is proportional to the sixth power of the river flow speed.[6] This formulation is also sometimes called Airy's law.[7] Thus, if the speed of flow is doubled, the flow would dislodge objects with 64 times as much submerged weight. In mountainous torrential zones, this can be seen as erosion channels through hard rocks and the creation of sands and gravels from the destruction of larger rocks. A river valley that was created from a U-shaped glaciated valley can often easily be identified by the V-shaped channel that it has carved.

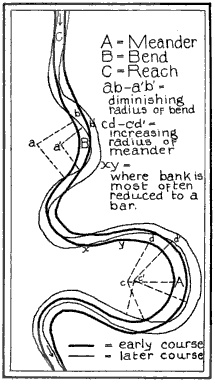

In the middle reaches where a river flows over flatter land, meanders may form through erosion of the river banks and deposition on the inside of bends. Sometimes the river will cut off a loop, shortening the channel and forming an oxbow lake or billabong. Rivers that carry large amounts of sediment may develop conspicuous deltas at their mouths. Rivers whose mouths are in saline tidal waters may form estuaries.

Throughout the course of the river, the total volume of water transported downstream will often be a combination of the free water flow together with a substantial volume flowing through sub-surface rocks and gravels that underlie the river and its floodplain (called the hyporheic zone). For many rivers in large valleys, this unseen component of flow may greatly exceed the visible flow.

Types and ratings

Rivers have been classified by many criteria including their topography, their biotic status, and their relevance to white water rafting or canoeing activities.

Subsurface rivers: subterranean and subglacial

Most but not all rivers flow on the surface. Subterranean rivers flow underground in caves. Such rivers are frequently found in regions with limestone geologic formations. Subglacial streams are the braided rivers that flow at the beds of glaciers and ice sheets, permitting meltwater to be discharged at the front of the glacier. Because of the gradient in pressure from the overlying weight of the glacier, such streams can even flow uphill.

Permanence of flow: perennial and ephemeral

An intermittent river (or ephemeral river) only flows occasionally and can be dry for several years at a time. These rivers are found in regions with limited or highly variable rainfall or can occur because of geologic conditions such as a highly permeable river bed. Some ephemeral rivers flow during the summer months but not in the winter. Such rivers are typically fed from chalk aquifers which recharge from winter rainfall. In England, these rivers are called bournes and give their name to places such as Bournemouth and Eastbourne. Even in humid regions, the location where flow begins in the smallest tributary streams generally moves upstream in response to precipitation and downstream in its absence or when active summer vegetation diverts water for evapotranspiration. Normally dry rivers in arid zones are often identified as arroyos or other regional names.

The meltwater from large hailstorms can create a slurry of water, hail, and sand or soil, forming temporary rivers.[8]

Stream order classification

The Strahler Stream Order ranks rivers based on the connectivity and hierarchy of contributing tributaries. Headwaters are first order while the Amazon River is twelfth order. Approximately 80% of the rivers in the world are of the first and second order.

The ways in which a river's characteristics vary between its upper and lower course are summarized by the Bradshaw model. Power-law relationships between channel slope, depth, and width are given as a function of discharge by "river regime".

In certain languages, distinctions are made among rivers based on their stream order. In French, for example, rivers that run to the sea are called fleuve, while other rivers are called rivière. For example, in Canada, the Churchill River in Manitoba is called la rivière Churchill as it runs to Hudson Bay, but the Churchill River in Labrador is called le fleuve Churchill as it runs to the Atlantic Ocean. As most rivers in France are known by their names only without the word rivière or fleuve (e.g. la Seine, not le fleuve Seine, even though the Seine is classed as a fleuve), one of the most prominent rivers in the Francophone commonly known as fleuve is le fleuve Saint-Laurent (the St. Lawrence River). Since many fleuves are large and prominent, receiving many tributaries, the word is sometimes used to refer to certain large rivers that flow into other fleuves; however, even small streams that run to the sea are called fleuve (e.g. fleuve côtier, "coastal fleuve").

Topographical classification

Rivers can generally be classified as either alluvial, bedrock, or some mix of the two. Alluvial rivers have channels and floodplains that are self-formed in unconsolidated or weakly consolidated sediments. They erode their banks and deposit material on bars and their floodplains.

Bedrock rivers form when the river downcuts through the modern sediments and into the underlying bedrock. This occurs in regions that have experienced some kind of uplift (thereby steepening river gradients) or in which a particularly hard lithology causes a river to have a steepened reach that has not been covered in modern alluvium. Bedrock rivers very often contain alluvium on their beds; this material is important in eroding and sculpting the channel. Rivers that go through patches of bedrock and patches of deep alluvial cover are classified as mixed bedrock-alluvial.

Alluvial rivers can be further classified by their channel pattern as meandering, braided, wandering, anastomose, or straight. The morphology of an alluvial river reach is controlled by a combination of sediment supply, substrate composition, discharge, vegetation, and bed aggradation.

Biotic classification

There are several systems of classification based on ecological conditions typically assigning classes from the most oligotrophic or unpolluted through to the most eutrophic or polluted.[9] Other systems are based on a whole ecosystem approach such as developed by the New Zealand Ministry for the Environment.[10] In Europe, the requirements of the Water Framework Directive has led to the development of a wide range of classification methods including classifications based on fishery status[11]

A system of river zonation used in francophone communities[12][13] divides rivers into three primary zones:

- The crenon is the uppermost zone at the source of the river. It is further divided into the eucrenon (spring or boil zone) and the hypocrenon (brook or headstream zone). These areas have low temperatures, reduced oxygen content, and slow-moving water.

- The rhithron is the upstream portion of the river that follows the crenon. It has relatively cool temperatures, high oxygen levels, and fast, turbulent, swift flow.

- The potamon is the remaining downstream stretch of river. It has warmer temperatures, lower oxygen levels, slow flow, and sandier bottoms.

Navigability

The international scale of river difficulty is used to rate the challenges of navigation – particularly those with rapids. Class I is the easiest and Class VI is the hardest.

Streamflow

Studying the flows of rivers is one aspect of hydrology.[14]

Characteristics

Direction

Rivers flow downhill with their power derived from gravity. A common misconception holds that all or most rivers flow from north to south, but this is not so: rivers flow in all directions of the compass and often have complex meandering paths.[15][16][17]

Rivers flowing downhill, from river source to river mouth, do not necessarily take the shortest path. For alluvial streams, straight and braided rivers have very low sinuosity and flow directly downhill, while meandering rivers flow from side to side across a valley. Bedrock rivers typically flow in either a fractal pattern, or a pattern that is determined by weaknesses in the bedrock, such as faults, fractures, or more erodible layers.

Rate

Volumetric flow rate, also known as discharge, volume flow rate, and rate of water flow, is the volume of water which passes through a given cross-section of the river channel per unit of time. It is typically measured in cubic metres per second (cumec) or cubic feet per second (cfs).

Volumetric flow rate can be thought of as the mean velocity of the flow through a given cross-section, times that cross-sectional area. Mean velocity can be approximated through the use of the law of the wall. In general, velocity increases with the depth (or hydraulic radius) and slope of the river channel, while the cross-sectional area scales with the depth and the width: the double-counting of depth shows the importance of this variable in determining the discharge through the channel.

Effects

Fluvial erosion

In its youthful stage, a river causes erosion in the watercourse, deepening the valley. Hydraulic action loosens and dislodges aggregate which further erodes the banks and the river bed. Over time, this deepens the river bed and creates steeper sides which are then weathered. The steepened nature of the banks causes the sides of the valley to move downslope causing the valley to become V-shaped.

Waterfalls also form in the youthful river valley where a band of hard rock overlays a layer of soft rock. Differential erosion occurs as the river erodes the soft rock more readily than the hard rock, this leaves the hard rock more elevated and stands out from the river below. A plunge pool forms at the bottom and deepens as a result of hydraulic action and abrasion.[18]

Flooding

Flooding is a natural part of a river's cycle. The majority of the erosion of river channels and the erosion and deposition on the associated floodplains occur during the flood stage. In many developed areas, human activity has changed the form of river channels, altering magnitudes and frequencies of flooding. Some examples of this are the building of levees, the straightening of channels, and the draining of natural wetlands.

In many cases, human activities in rivers and floodplains have dramatically increased the risk of flooding. Straightening rivers allows water to flow more rapidly downstream, increasing the risk of flooding places further downstream. Building on flood plains removes flood storage, which again exacerbates downstream flooding. The building of levees only protects the area behind the levees and not those further downstream. Levees and flood banks can also increase flooding upstream because of the back-water pressure as the river flow is impeded by the narrow channel banks. Detention basins finally also reduce the risk of flooding significantly by being able to take up some of the flood water.

Sediment yield

Sediment yield is the total quantity of particulate matter (suspended or bedload) reaching the outlet of a drainage basin over a fixed time frame. Yield is usually expressed as kilograms per square kilometre per year. Sediment delivery processes are affected by a myriad of factors such as drainage area size, basin slope, climate, sediment type (lithology), vegetation cover, and human land use/management practices.

The theoretical concept of the 'sediment delivery ratio' (ratio between yield and total amount of sediment eroded) indicates that not all of the sediment is eroded within a certain catchment that reaches out to the outlet (e.g., deposition on floodplains). Such storage opportunities are typically increased in catchments of larger size, thus leading to a lower yield and sediment delivery ratio.

Brackish water

Brackish water occurs in most rivers where they meet the sea. The extent of brackish water may extend a significant distance upstream, especially in areas with high tidal ranges.

Ecosystem

River biota

The organisms in the riparian zone respond to changes in river channel location and patterns of flow. The ecosystem of rivers is generally described by the river continuum concept, which has some additions and refinements to allow for dams and waterfalls and temporary extensive flooding. The concept describes the river as a system in which the physical parameters, the availability of food particles, and the composition of the ecosystem are continuously changing along its length. The food (energy) that remains from the upstream part is used downstream.

The general pattern is that the first-order streams contain particulate matter (decaying leaves from the surrounding forests) which is processed there by shredders like Plecoptera larvae. The products of these shredders are used by collectors, such as Hydropsychidae, and further downstream algae that create the primary production become the main food source of the organisms. All changes are gradual and the distribution of each species can be described as a normal curve, with the highest density where the conditions are optimal. In rivers, succession is virtually absent and the composition of the ecosystem stays fixed.

Chemistry

The chemistry of rivers is complex and depends on inputs from the atmosphere, the geology through which it travels, and the inputs from man's activities. The chemical composition of the water has a large impact on the ecology of that water for both plants and animals and it also affects the uses that may be made of the river water. Understanding and characterizing river water chemistry requires a well-designed and managed sampling and analysis.

Uses

Construction material

The coarse sediments, gravel, and sand, generated and moved by rivers are extensively used in construction. In parts of the world, this can generate extensive new lake habitats as gravel pits fill with water. In other circumstances, it can destabilize the river bed, and the course of the river and cause severe damage to spawning fish populations that rely on stable gravel formations for egg-laying. In upland rivers, rapids with whitewater or even waterfalls occur. Rapids are often used for recreation, such as whitewater kayaking.[19]

Energy production

Fast-flowing rivers and waterfalls are widely used as sources of energy, via watermills and hydroelectric plants. Evidence of watermills shows them in use for many hundreds of years, for instance in Orkney at Dounby Click Mill. Prior to the invention of steam power, watermills for grinding cereals and for processing wool and other textiles were common across Europe. In the 1890s the first machines to generate power from river water were established at places such as Cragside in Northumberland and in recent decades there has been a significant increase in the development of large-scale power generation from water, especially in wet mountainous regions such as Norway.

Food source

Rivers have been a source of food since pre-history.[20] They are often a rich source of fish and other edible aquatic life and are a major source of fresh water, which can be used for drinking and irrigation. Rivers help to determine the urban form of cities and neighborhoods, and their corridors often present opportunities for urban renewal through the development of foreshoreways such as river walks. Rivers also provide an easy means of disposing of wastewater and, in much of the less developed world, other wastes.

Navigation and transport

Rivers have been used for navigation for thousands of years. The earliest evidence of navigation is found in the Indus Valley civilization, which existed in northwestern India around 3300 BC.[21] Riverine navigation provides a cheap means of transport and is still used extensively on most major rivers of the world like the Amazon, the Ganges, the Nile, the Mississippi, and the Indus.

In some heavily forested regions such as Scandinavia and Canada, lumberjacks use rivers to float felled trees downstream to lumber camps for further processing, saving much effort and cost by transporting the huge heavy logs by natural means.[22]

Political borders

Rivers have been important in determining political boundaries and defending countries. For example, the Danube was a long-standing border of the Roman Empire, and today it forms most of the border between Bulgaria and Romania. The Mississippi in North America and the Rhine in Europe are major east–west boundaries in those continents. The Orange and Limpopo Rivers in southern Africa form the boundaries between provinces and countries along their routes.

Sacred rivers

Sacred rivers are examples of sacred natural sites and their reverence is a phenomenon found in several religions, especially religions in which nature is revered. For example, the Indian-origin religions of Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and Sikhism revere and preserve groves, forests, trees, mountains, and rivers as sacred. Among the most sacred rivers in Hinduism are the Ganges,[23] Yamuna,[24][25] and Sarasvati[26] rivers. Other sacred rivers for Indian religions include the Rigvedic rivers, the Narmada, the Godavari, and the Kaveri rivers. The Vedas and Gita, the most sacred of Hindu texts, were written on the banks of the Sarasvati river.

Management

Rivers are often managed or controlled to make them more useful or less disruptive to human activity.

- Dams or weirs may be built to control the flow, store water, or extract energy.

- Levees, known as dikes in Europe, may be built to prevent river water from flowing on floodplains or floodways.

- Canals connect rivers to one another for water transfer or navigation.

- River courses may be modified to improve navigation or straightened to increase the flow rate.

River management is a continuous activity as rivers tend to 'undo' the modifications made by people. Dredged channels silt up, sluice mechanisms deteriorate with age, and levees and dams may suffer seepage or catastrophic failure. The benefits sought through managing rivers may often be offset by the social and economic costs of mitigating the bad effects of such management. As an example, in parts of the developed world, rivers have been confined within channels to free up flat flood-plain land for development. Floods can inundate such development at high financial cost and often with loss of life.

Rivers are increasingly managed for habitat conservation, as they are critical for many aquatic and riparian plants, resident and migratory fishes, waterfowl, birds of prey, migrating birds, and many mammals.

Concerns

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2021) |

Human-made causes, such as the over-exploitation and pollution, are the biggest threats and concerns which are making rivers ecologically dead and drying up the rivers.

Plastic pollution imposes threats on aquatic life and river ecosystems because of plastic's durability in the natural environment. Plastic debris may result in entanglement and ingestion by aquatic life such as turtles, birds, and fish, causing severe injury and death. Human livelihoods around rivers are also impacted by plastic pollution through direct damage to shipping and transport vessels, effects on tourism or real estate value, and the clogging of drains and other hydraulic infrastructure leading to increased flood risk.[27]

See also

- Arts, entertainment, and media

- "Old Man River"

- The Riverkeepers (book)

- General

- Crossings

- Habitats

- Lists

- Transport

References

- ^ a b "What is the difference between "mountain", "hill", and "peak"; "lake" and "pond"; or "river" and "creek?"". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "WordNet Search: River". The Trustees of Princeton University. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ Basic Biology (16 January 2016). "River".

- ^ see for example John Speed's atlas 'The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine' published in 1611 and 1612 and the UK 'Old Series' of Ordnance Survey maps (1817–1830)

- ^ Walther, John V. (2013). Earth's Natural Resources. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4496-3234-2.

- ^ Garde, R.J. (1995). History of fluvial hydraulics. New Age Publishers. p. 14. ISBN 978-81-224-0815-7. OCLC 34628134.

- ^ Garde, R.J. (1995). History of fluvial hydraulics. New Age Publishers. p. 19. ISBN 978-81-224-0815-7. OCLC 34628134.

- ^ ""Sand River" in Iraq is actually a rapid movement of ice blocks". tampabayreview.com. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ River Classification scheme. sepa.org.uk

- ^ NZ's River Environment Classification system (REC). maf.govt.nz

- ^ Noble, Richard and Cowx, Ian et al. (May 2002) Compilation and harmonisation of fish species classification Archived 3 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. University of Hull, UK. A project under the 5th Framework Programme Energy, Environment and Sustainable Management. Key Action 1: Sustainable Management and Quality of Water

- ^ Illies, J.; Botosaneanu, L. (1963). "Problémes et méthodes de la classification et de la zonation éologique des eaux courantes, considerées surtout du point de vue faunistique". Mitt. Int. Ver. Theor. Angew. Limnol. 12: 1–57.

- ^ Hawkes, H.A. (1975). River zonation and classification. Blackwell. pp. 312–374.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Cave, Cristi. "How a River Flows". Stream Biology and Ecology. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015.

- ^ Rosenberg, Matt (8 June 2006). "Do All Rivers Flow South?". About.com. Archived from the original on 1 June 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

- ^ Rosenberg, Matt. "Rivers Flowing North: Rivers Only Flow Downhill; Rivers Do Not Prefer to Flow South". About.com. Archived from the original on 4 April 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

- ^ Rydell, Nezette (16 March 1997). "Re: What determines the direction of river flow? Elevation, Topography, Gravity??". Earth Sciences.

- ^ "Landforms of the upper valley". www.coolgeography.co.uk. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ Draper, Nick; Hodgson, Christopher (2008). Adventure Sport Physiology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-31913-0.

- ^ "National Museum of Prehistory-The Peinan Site-Settlements of the Prehistoric Times". nmp.gov.tw.

- ^ "WWF – The World's Rivers" Archived 15 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine. panda.org.

- ^ "Logging Camps: The Early Years". Minnesota DNR.

- ^ Alter, Stephen (2001), Sacred Waters: A Pilgrimage Up the Ganges River to the Source of Hindu Culture, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Trade & Reference Publishers, ISBN 978-0-15-100585-7, retrieved 30 July 2013

- ^ Jain, Sharad K.; Pushpendra K. Agarwal; Vijay P. Singh (2007). Hydrology and water resources of India – Volume 57 of Water science and technology library. Springer. pp. 344–354. ISBN 978-1-4020-5179-1.

- ^ Hoiberg, Dale (2000). Students' Britannica India, Volumes 1-5. Popular Prakashan. pp. 290–291. ISBN 0-85229-760-2.

- ^ "Sarasvati | Hindu deity". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2 May 2023.

- ^ van Emmerik, Tim; Schwarz, Anna (January 2020). "Plastic debris in rivers". WIREs Water. 7 (1). doi:10.1002/wat2.1398.

Further reading

- Luna B. Leopold (1994). A View of the River. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-93732-1. OCLC 28889034. – a non-technical primer on the geomorphology and hydraulics of water.

- Middleton, Nick (2012). Rivers: a very short introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958867-1.