Gentile Budrioli

Gentile Budrioli (died 14 July 1498), also known as Gentile Cimieri,[5] was an Italian astrologist and herbal healer active in Bologna in the late 15th century. She studied at the University of Bologna and also received lessons from Franciscan friars. Budrioli drew attention from her contemporaries for her great skill in healing and she became a close friend of Ginevra Sforza, the wife of Bologna's ruler Giovanni II Bentivoglio. As a result of this, Budrioli rapidly rose through the ranks in the city and briefly served as a councilor at the Bolognese court.

Budrioli's rise to prominence drew the envy of others and in 1498 she was accused of witchcraft after she failed to save one of Bentivoglio's sons from an unknown disease. Budrioli's case was handled by the Inquisition, who fabricated evidence and tortured her. At her trial, numerous people came out to support the claims of her being a witch, including her own husband Alessandro, who had staunchly opposed her scientific interests. Budrioli was simultaneously hanged and burnt alive in front of a crowd of onlookers at the Piazza San Domenico in Bologna.

Early life

[edit]Gentile Budrioli was a noblewoman born into a wealthy family in Bologna.[1][3] She was non-conformist and scientifically interested from an early age.[6]

Budrioli married the rich notary Alessandro Cimieri,[1][7][8] who owned a home in the Torresotto di Porta Nuova, opposite the Basilica of Saint Francis in Bologna.[1] The marriage was arranged by her father due to Cimieri being from another well-off family and reportedly being of mild character; Budrioli's father perhaps believed that the man could constrain his daughter's aspirations.[6] Budrioli and Cimieri had seven children together: three daughters and four sons (one of whom was named Carlo).[9]

Education and rise

[edit]Emerging from the surviving sources as a rich, educated and beautiful woman,[1] Budrioli found her married life with Cimieri to be boring.[6] She retained her deep interest in science, much to her husband's dismay.[1][6] Budrioli attended lessons and lectures at the University of Bologna,[1] particularly astrology lessons held by the professor Scipione Manfredi.[1][6] When her husband found out about the astrology lessons, he prevented her from attending them any more.[4] In addition to university studies, Budrioli also sought out the Franciscan friar Silvestro at a Franciscan convent near her home, from which she learnt herbal healing arts.[1] For a time, Budrioli reportedly met with Silvestro every day to learn.[6]

Over time, Budrioli acquired great medical expertise, becoming considered by many to be better than the professional physicians in Bologna.[6] She made her expertise available to the other city residents, helping them with both physical and psychological afflictions.[1] Among her most high-profile patients were Ginevra Sforza, the wife of Giovanni II Bentivoglio, the ruler of Bologna. Sforza first approached Budrioli due to having pains relating to childbirth. The two quickly became close friends,[6] bonding over a shared interest in esotericism.[3] Budrioli and Sforza often spent whole afternoons and evenings talking and reading together.[6] Budrioli's expertise and her friendship with Sforza allowed her to quickly rise through the ranks in the city and she was before long made a councilor at Bentivoglio's court.[1]

Accusation of witchcraft

[edit]As a knowledgeable woman who did not keep her influence and scientific expertise a secret, some among the nobility of Bologna viewed Budrioli with suspicion.[10] Her quick rise to power also made her a target of envy and slander from other influential personalities in the city.[1] When Budrioli failed to save one of Bentivoglio's sick sons from an unknown disease despite trying her best for several days,[1][11] the Malvezzi family, a rival family to the Bentivoglios, exploited the opportunity and claimed that Budrioli had in fact caused the child's illness through witchcraft.[10] She was further accused of being behind several other negative events in the city.[1] It is possible that the accusations against Budrioli were a veiled attack against Sforza, who was too powerful to be attacked directly.[9] Accusations of witchcraft were during this time common not only due to superstition and political aspirations, but also due to economic incentives; if someone was executed for withcraft, their belongings were confiscated and divided between the church and the local government.[10]

Trial and torture

[edit]

Bentivoglio was reportedly convinced by the accusations[1] and Budrioli was arrested immediately.[6] Executing Budrioli as a witch was perhaps a scheme on Bentivoglio's part to improve his relationship with Pope Alexander VI, who at the time threatened to place Bologna under papal control.[4] Sforza did nothing to defend her, perhaps fearing that she too would face punishment if she did.[6]

Budrioli's case was handled by the Inquisition,[1] which was often particularly violent towards women accused of witchcraft.[6] The local Inquition had reportedly kept an eye on her activities for some time, waiting for a misstep.[4] Shortly after Budrioli was imprisoned, the Inquisition judges raided her home and "discovered evidence" of witchcraft, such as traces of blood, an assortment of cloaks, ampules with various liquids and an altar.[6]

Following the raid, Budrioli was formally put on trial. Numerous witnesses came forth to support that Budrioli was a witch.[6] Due to Budrioli's fascination for both astrology and healing herbs, it was not difficult to convince the townspeople of her guilt.[8] One of Budrioli's servants claimed that she had taught her a love spell. Cimieri, Budrioli's own husband, also accused her of witchcraft, claiming that she had cast a spell on him which hampered his intellect.[6] There were also claims made that she had cast spells on her brother Ercole.[3] Some of the witnesses claimed that Budrioli was able to predict the future from looking at the stars.[6]

After the trial, the inquisitors made a second search of her residence and found further evidence that they had somehow missed the first time, including desecrated holy symbols, another altar with images of Lucifer, twelve bags containing human organs, and bones stolen from a cemetery.[6] After several days of horrific torture[1][3][6] and just before the interrogators were going to begin removing her limbs,[9] Budrioli confessed to having practiced the occult for two decades, a crime she was not guilty of.[3] According to the Italian historian Giovanni Battista Sezanne, Budrioli's confession was as follows:[9]

"Oh, for heaven's sake take me away from these pains of hell! ... I will say, I will say anything. I confess to everything that was raised against me by the witnesses ... is that not enough for you, gentlemen? Let me hug my children and my husband once more and then ... kill me.[9]

Execution

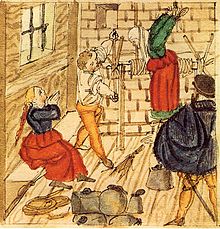

[edit]On the morning of 14 July 1498,[1][6][9] Budrioli was taken to the Piazza San Domenico,[1] just opposite of her home.[4] There she was sprinkled with pitch and a noose was tied around her neck; Budrioli was hanged and burnt simultaneously.[6] The officials in charge of the burning threw gunpowder on the fire to entertain the onlookers.[1] Many of the onlookers were convinced that the extra flames were caused by the devil, who they believed came to retrieve Budrioli's soul.[6][12] Budrioli received no burial after the burning, her ashes being scattered in the wind.[6]

Sforza did not attend the burning, reportedly being at Budrioli's residence at the time and weeping.[3][6] After the burning, Sforza took care of Budrioli's daughters, arranging favorable marriages for some and placing others in convents.[8]

Legacy

[edit]The Italian historian Leandro Alberti (1479–1552) devoted two pages of his history of Bologna (Istoria di Bologna, etc., published in two volumes in 1514 and 1543) to Budrioli's story and her execution.[4] Budrioli remains remembered to this day as strega enormissima di Bologna, the "great witch of Bologna".[1][2][3] Budrioli was in 2018 cited by the Italian writer Barbara Baraldi as one of many women throughout history who had to pay a steep price for being ahead of their time.[9] A musical was created by the Accademia Culturale dei Castelli in Aria in 2011 based on the friendship of Budrioli and Sforza, titled Ginevra e Gentile ("Ginevra and Gentile").[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Gentile Budrioli, "strega enormissima" di Bologna" [Gentile Budrioli, "Great Witch" of Bologna]. Genus Bononiae (in Italian). 2018-07-11. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- ^ a b Reali, Rosella (2017-01-14). "Gentile, la strega enormissima" [Gentile, the Great Witch]. Viaggiatori Ignoranti (in Italian). Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Meroe, Strega (6 January 2017). "Gentile Budrioli – Strega Enormissima di Bologna" [Gentile Budrioli – Great Witch of Bologna]. Strega Viaggiatrice (in Italian). Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- ^ a b c d e f "Gentile e Ginevra: l'incrocio di due vite vissute pericolosamente" [Gentile and Ginevra: the Crossing of Two Lives Lived Dangerously]. Sentieri Sterrati A.P.S. (in Italian). 2018-04-14. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ Dolfo, Floriano (2002). Lettere ai Gonzaga [Letters to the Gonzagas] (in Italian). Rome: Istituto Nazionale di Studi sul Rinascimento. p. 589. ISBN 978-8887114522.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Casalini, Fabio; Reali, Rosella (2018). "Gentile Budrioli, la "Strega Enormissima"" [Gentile Budrioli, the "Great Witch"]. È una Storia da Non Raccontare [A Story Not to be Told] (in Italian). Rome: Gruppo Albatros. ISBN 978-88-567-9403-8.

- ^ Parmeggiani, Riccardo (2018). "Mendicant Orders and the Repression of Heresy". In Blanshei, Sarah Rubin (ed.). A Companion to Medieval and Renaissance Bologna. Leiden: BRILL. p. 429. ISBN 9789004353480.

- ^ a b c Bersani, Serena (2015). "24. Gentile Budrioli, la fine di una strega" [24. Gentile Budrioli, the end of a witch]. 101 donne che hanno fatto grande Bologna [101 women who made Bologna great] (in Italian). Rome: Newton Compton Editori. ISBN 978-88-541-8260-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Baraldi, Barbara (2018). "Perché il torresotto di Porto Nova è stregato?" [Why is Porta Nuova bewitched?]. 101 perché sulla storia di Bologna che non puoi non sapere [101 stories from the history of Bologna that you need to know] (in Italian). Rome: Newton Compton Editori. ISBN 978-88-227-2628-5.

- ^ a b c Casalini, Fabio; Reali, Rosella (2018). "Gentile Budrioli, la "Strega Enormissima"" [Gentile Budrioli, the "Great Witch"]. È una Storia da Non Raccontare [A Story Not to be Told] (in Italian). Rome: Gruppo Albatros. ISBN 978-88-567-9403-8.

- ^ "Gentile e Ginevra: l'incrocio di due vite vissute pericolosamente" [Gentile and Ginevra: the Crossing of Two Lives Lived Dangerously]. Sentieri Sterrati A.P.S. (in Italian). 2018-04-14. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ Servadio, Gaia (2005). Renaissance woman. London ; New York : I.B. Tauris ; New York : Distributed by Palgrave Macmillan in the United States and Canada. ISBN 978-1-85043-421-4 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Ginevra e Gentile". Accademia Culturale dei Castelli in Aria. Archived from the original on 2012-05-30. Retrieved 2022-05-25.