Battle of Qarqar

| Battle of Qarqar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Assyrian conquest of Aram | |||||||

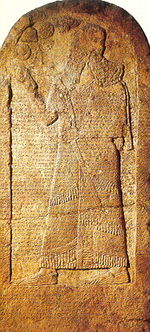

Kurkh stele of Shalmaneser depicting the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Neo-Assyrian Empire |

12 Kings alliance: Hama Israel Aram-Damascus Ammon Qedar Arwad Quwê Irqanata Shianu | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Shalmaneser III |

Irhuleni of Hama Ahab of Israel Hadadezer of Aram-Damascus Baʻsa of Ammon Gindibu of Qedar Matinu Baal of Arwad Kate of Quwê Adunu Baal of Shianu | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

35,000, including:[1] 20,000 infantry, 12,000 cavalry, 1,200 chariots,[2] |

53,000–63,000 infantry, 4,000 chariots, 2,000 cavalry, 1,000 camel cavalry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

The Battle of Qarqar (or Ḳarḳar) was fought in 853 BC when the army of the Neo-Assyrian Empire led by Emperor Shalmaneser III encountered an allied army of eleven kings at Qarqar led by Hadadezer, called in Assyrian Adad-idir and possibly to be identified with King Benhadad II of Aram-Damascus; and Ahab, king of Israel.[3] This battle, fought during the 854–846 BC Assyrian conquest of Aram, is notable for having a larger number of combatants than any previous battle, and for being the first instance in which some peoples enter recorded history, such as the Arabs. The battle is recorded on the Kurkh Monoliths. Using a different rescension of the Assyrian Eponym List would put the battle's date at 854 BC.[4]

The ancient town of Qarqar at which the battle took place has generally been identified with the modern-day archaeological site of Tell Qarqur near the village of Qarqur in Hama Governorate, northwestern Syria.

According to an inscription later erected by Shalmaneser, he had started his annual campaign, leaving Nineveh on the 14th day of Iyar. He crossed both the Tigris and Euphrates without incident, receiving the submission and tribute of several cities along the way, including Aleppo. Once past Aleppo he encountered his first resistance from troops of Irhuleni, king of the Luwian state of Ḥamā (called in Hebrew Ḥamāth), whom he defeated; in retribution, he plundered both the palaces and the cities of Irhuleni's kingdom. Continuing his march after having sacked Qarqar, he encountered the allied forces near the Orontes River.[5]

Twelve kings

[edit]Twelve Kings is an Akkadian term meant to symbolize any kind of alliance.[citation needed] The most famous example is in the Kurkh Monoliths, where an alliance of 11 kings are listed as 12 in the Assyrian document as fighting against Assyrian King Shalmaneser III in the battle of Qarqar.[6] Shalmaneser's inscription describes the forces of his opponent Hadadezer in considerable detail as follows:[7]

- King Hadadezer himself commanded 1,200 chariots, 1,200 horsemen and 20,000 soldiers;

- King Irhuleni of Hamath commanded 700 chariots, 700 horsemen and 10,000 soldiers;

- King Ahab of Israel sent 2,000 chariots and 10,000 soldiers (the number of Ahab's forces is a subject of controversy among scholars);

- The Kingdom of KUR Gu-a-a identified as Quwê-Cilicia sent 500 soldiers;

- The land of KUR Mu-us-ra-[a] identified as Masura, which is the outlet of the Düden River, sent 1,000 soldiers;

- The land of Irqanata (Tell Arqa) sent 10 chariots and 10,000 soldiers;

- King Matinu Baal of Arwad sent 200 soldiers;

- The land of Usannata[b] (in the Mount Lebanon region) sent 200 soldiers;

- King Adunu Baal of Ušnatu (in the Syrian Coastal Mountain Range)[8] – figures lost;

- King Gindibu of Arabia sent 1,000 camel cavalry;

- King Ba'asa, son of Ruhubi, of the land of Ammon sent 100 soldiers.

The number of forces sent in by Ahab is a subject of controversy among scholars, since it seems unlikely that the Kingdom of Israel could possess an army superior to that of the Kingdom of Aram-Damascus. The number of chariots in Ahab's forces was probably closer to a number in the hundreds (based upon archaeological excavations of the area and the foundations of stables that have been found). Although some scholars have argued that Israel under king Ahab would not have been able to muster a force of 2,000 chariots, there is some archeological evidence that supports the biblical account. Archeological excavations conducted by The Oriental Institute at Tel Meggido uncovered a large complex of stables. Some scholars suggest that these were not actually stables, but scholars such as Yadin, Finkelstein, and Ussishkin, say that they are indeed stables. The stables they uncovered housed 150 chariots and were dated to the 9th century BCE, which would align with the reign of King Ahab. If Ahab had stables of this size throughout his kingdom, it would suggest that he would be able to raise a substantial force. A building complex similar to the one at Megiddo was also uncovered at the city of Be’er Shiva.[9] Archaeologist Nadav Na'aman believes it to be a scribal error in regard to the size of Ahab's army and suggested that he sent 200 instead of 2,000 chariots. Another possible explanation is that the forces attributed to Ahab include those belonging to his allies, such as the Kingdom of Judah, the Kingdom of Tyre and the Kingdom of Moab, although those kingdoms are not named in the monolith.

Battle

[edit]The Battle according to Shalmaneser:

With the supreme forces which Aššur, my lord, had given me and with the mighty weapons which the divine standard, which goes before me, had granted me, I fought with them. I decisively defeated them from the city of Qarqar to the city of Gilzau. I felt with the sword 14,000 troops, their fighting men. Like Adad, I rained down upon them a devastating flood. I spread out their corpses and I filled the plain. I felled with the sword their extensive troops. I made their blood flow in the wadis. The field was too small for laying flat their bodies; the broad countryside had been consumed in burying them. I blocked the Orontes river with their corpses as with a causeway. In the midst of the battle I took away from them chariots, cavalry, and teams of horses.[10]

However, the royal inscriptions from this period are notoriously unreliable. They never directly acknowledge defeats and sometimes claim victories that were actually won by ancestors or predecessors. If Shalmaneser had won a clear victory at Qarqar, it did not immediately lead to further Assyrian conquests in Syria.[11] Assyrian records make it clear that he campaigned in the region several more times in the following decade, engaging Hadadezer six times, who was supported by Irhuleni of Hama at least twice. Shalmaneser's opponents held on to their thrones after this battle: though Ahab of Israel died shortly afterwards in an unrelated battle, Hadadezer was king of Damascus until at least 841 BC.

Notes

[edit]^ a: Mu-us-ra- is sometimes identified with Egypt, but lay possibly somewhere near Quwê. Another thesis identifies Mu-us-ra- with Phoenician Sumur, in Syria.[12]

^ b: Also spelled as "Usanta".

References

[edit]- ^ Gabriel, Richard A. (2002). The Great Armies of Antiquity. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-275-97809-9.

- ^ Gabriel, Richard A. (2003). The Military History of Ancient Israel. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-275-97798-6.

- ^ "Battle of Qarqar". Biblical Archaeology - Maps and Findings. Retrieved 3 July 2024.

- ^ Shea, William H. "A Note on the Date of the Battle of Qarqar." Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 29, no. 4, 1977, pp. 240–242

- ^ ""Qarqar and Current Events", Lofquist, L". Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ^ אולשניצקי), Haggai Olshanetsky (חגי (1 January 2020). "The Twelve Make a Stand: The Kingdom of Israel's Chariot Force and the Battle of Qarqar". Ancient Warfare.

- ^ Bunnens, Guy; Hawkins, J.D.; Leirens, I. (2006). Tell Ahmar II. A New Luwian Stele and the Cult of the Storm-God at Til Barsib-Masuwari. Leuven,Belgium: Peeters. pp. 90/1. ISBN 978-90-429-1817-7.

- ^ "سيانو".. المملكة التي يعود نسل أهلها إلى سابع أبناء كنعان. esyria.sy (in Arabic). 4 October 2009.

- ^ Coogan 2009, p. 243.

- ^ "Qarqar (853 BCE) - Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ Malamat, Abraham (1976). A History of the Jewish People. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-39731-6.

- ^ Edward Lipiński (2006). On the Skirts of Canaan in the Iron Age: Historical and Topographical Researches. Peeters Publishers. p. 132. ISBN 9789042917989.

Sources

[edit]- Coogan, Michael David (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament: The Hebrew Bible in Its Context. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533272-8.