Corleck Head

| The Corleck Head | |

|---|---|

Two of the head's three faces | |

| Material | Limestone |

| Size |

|

| Created | 1st or 2nd century AD |

| Discovered | c. 1855 Corleck Hill, County Cavan, Ireland 53°58′21″N 6°59′53″W / 53.9725°N 6.9981°W |

| Present location | National Museum of Ireland, Dublin |

| Identification | IA:1998:72[1] |

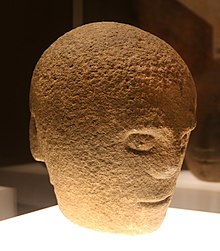

The Corleck Head is a three-faced stone idol usually dated to the 1st or 2nd century AD. Each face has a similarly enigmatic expression, closely set eyes, a broad, flat nose, and a simply drawn mouth. Although its origin cannot be known for certain, its dating to the Early Iron Age is based on similar iconography from contemporary northern European Celtic artefacts. Archaeologists agree that it represents a Celtic god, and was part of a larger shrine associated with a Celtic head cult, and may have become used during the Lughnasadh harvest festivals.

The head was found c. 1855 in the townland of Drumeague in County Cavan, Ireland, during the excavation of a large passage tomb dated to c. 2500 BC. The archaeological evidence indicates that it was used for ceremonial purposes at Corleck Hill, a significant cult centre during the late Iron Age that for millennia became a major site of celebration during the Lughnasadh. As with any stone artefact, its dating and cultural significance are difficult to establish. The three faces may represent an all-knowing, all-seeing god representing the unity of the past, present and future or ancestral mother figures representing strength and fertility. The head was found alongside the Corraghy head, a two-headed sculpture with a ram's head at one side and a human head on the other. Today only the human head survives. The idols are collectively known as the "Corleck Gods". Historians assume that they were hidden during the Early Middle Ages due to their paganism and association with human sacrifice, traditions the early Christian church suppressed.

It came to national attention in 1937 after its prehistoric dating was realised by the historian Thomas J. Barron; when found it was a local curiosity placed on top of a farm gatepost. Today it is on permanent display at the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin. It is listed as number 11 in the 2011 Irish Times anthology A History of Ireland in 100 Objects.[2]

Description

[edit]

The Corleck Head is cut from local limestone,[3] and is a relatively large example of the Irish stone idol type, being 33 cm (13 in) high and 22.5 cm (8.9 in) at its widest point.[4] The faces, which could be male or female[5] are carved in low relief.[6] They are similar but not identical in form and expression; each seems to indicate a slightly different mood.[7] They all have enigmatic expressions and very basic and simply described facial features. Each has a broad and flat wedge–shaped nose and a thin, narrow, slit mouth. The embossed eyes are wide and round, yet closely-set and seem to stare at the viewer. The faces are all clean-shaven and lack ears, while the head overall is cut off before the neck.[2][8] One has heavy eyebrows, another has a small hole at the centre of its mouth, a feature of unknown significance found on several Irish contemporary stone heads and examples from England, Wales and Bohemia.[9][10]

The hole under the sculpture's base suggests it was intended to be placed on top of a pedestal, likely on a tenon (a joint connecting two pieces of material).[11] This indicates that the overall structure may have represented a phallus, a common Iron age fertility symbol,[12] and was intended as part of a larger pre–Christian shrine.[7][13]

The head is widely considered the finest Irish example of the type due to its contrasting simplicity of design and complexity of expression.[14][7] In 1972, the archaeologist and historian Etienn Rynne described it as "unlike all others in its elegance and economy of line",[11] while in 1962 the archaeologist Thomas G. F. Paterson wrote that only the triple-head idol found in Cortynan, County Armagh, shares features drawn from such bare outlines. According to Paterson, the simplicity of the Corleck and Cortynan heads indicates a degree of sophistication of craft absent in the often "vigorous and ... barbaric style" of other contemporary Irish examples.[15]

Discovery

[edit]

The head was unearthed around 1855 by the local farmer James Longmore while collecting stones to build a farmhouse, which became known colloquially as the "Corleck Ghost House".[18][19][20] While the exact find spot is unknown,[14] it was probably in the nearby townland of Drumeague on the site of a large c. 2500 BC passage tomb that was then under excavation.[21][4] The head was uncovered along with the Corraghy head; a janiform sculpture with a ram's head on one side and a human head with hair and a beard on the other.[21][20] Archaeologists assumed they once formed elements of a large shrine and were buried around the same time, perhaps to hide them from early Christians keen to eradicate the worship of pagan idols.[22]

The next lease-holder of the farm, Sam Hall, placed the head on a gatepost.[23] Emily Bryce, a relative of the Halls, remembered childhood visits throwing stones at it.[1] The local historian and folklorist Thomas J. Barron was the first to recognise its age and significance after seeing it in 1934 while a researcher for the Irish Folklore Commission.[24][23] The following year, Barron interviewed the 87-year-old local man John Reilly, who had early memories of viewing the heads at the school in Corleck, shortly after they had been discovered by Longmore.[23]

Barron contacted the National Museum of Ireland (NMI) in 1937,[4] after which the NMI director Adolf Mahr arranged its permanent loan to the museum for study.[16] In a lecture to The Prehistoric Society that year, Mahr described the head as "certainly the most Gaulish looking sculpture of religious character ever found in Ireland".[23] Mahr secured funding to acquire it for the museum,[1][17] while study of the head and similar stone idols preoccupied Barron until his death in 1992.[17][25]

Dating

[edit]Dating single pieces of stone sculpture is extremely difficult given that techniques such as radiocarbon dating cannot be used.[26] Most surviving iconic (representational, as opposed to abstract) prehistoric Irish sculptures originate from the northern province of Ulster. The majority consist of human heads carved in the round in low relief. Most are thought to have been produced between 300 BC and 100 AD, that is at the end of the La Tène period in Ireland.[27][28]

Although many of the Ulster heads are now believed to be pre-Christian, a large number of others have since been identified as either from the Early Middle Ages or examples of 17th- or 18th-century folk art.[a] Thus modern archaeologists date such objects based on their resemblance to other known examples in the contemporary Northern European context.[29][13] The Corleck Head's format and details were likely influenced by a wider European tradition, in particular from contemporary Romano-British and Gallo-Roman iconography.[7][30] A small number of faces on contemporary Irish and British anthropomorphic examples have similar closely-set eyes, simply-drawn mouths and broad noses,[31][32] including a three-faced stone bust from Woodlands, County Donegal, and two carved triple-heads from Greetland in West Yorkshire, England.[4][33] Similar janiform idols include the "Lustymore" figure on Boa Island and the head found in Caldragh, County Fermanagh. on the lower part of Lough Erne.[34][35]

Corleck Hill

[edit]Corleck Hill and the nearby area once held three Neolithic passage graves, the largest of which was known locally as the "giants grave" and excavated during the 18th and 19th centuries, both to make way for farming land and to reuse its stones for building material.[20][36] One local, Jon O'Reilly, described to Barron how, at least until 1836, Corleck Hill had a passage tomb and a stone circle on its peak. According to O'Reilly, during the tomb's excavation, the entrance stones were "drawn away ... [revealing] a cruciform shaped chamber ... the stones from the mound were used to build a dwelling house nearby, known locally as Corleck Ghost House."[20]

The area is known in Irish as Sliabh na Trí nDée (the "Hill of the Three Gods") or Sliabh na nDée Dána (the "Highland of the Three Gods of Craftsmanship"). The archaeological evidence indicates that Corleck was a significant Druidic place of worship and learning during the early Iron Age;[37][38] and was once known as "the pulse of Ireland".[37][39] Corleck is traditionally associated with the Lughnasadh, an ancient harvest festival celebrating the Celtic god Lugh, believed to have been a warrior, king and master craftsman of the Tuatha Dé Danann — one of the foundational ancient Irish tribes in Irish mythology.[40][41] Archaeologists think the head was one of a series of objects placed at the site during the festival. According to the historian Jonathan Smyth, it was probably situated on top of a pillar as part of a phallic symbol representing fertility.[4][42]

Corleck is one of six areas in Ulster where clusters of presumably related stone idols have been found.[b][43] Other cult objects from the broader area include the 1st century BC wooden Ralaghan Idol, also brought to attention by Barron[c][36][44] and the contemporary stone heads from the nearby townlands of Corravilla (a small spherical head) and Corraghy (a bearded head with an unusually long neck, now also in the NMI).[11][15] The Corleck and Corraghy heads are presumed to have been hidden around the same time.[4][45]

Function

[edit]The Corleck Head is one of the earliest known figurative (iconic) stone sculptures found in Ireland, with the exception of the c. 1000 – c. 500 BC Tandragee Idol from nearby County Armagh, which may also have been produced for a cult site.[13]

Although historical knowledge of the Irish Celts is, according to the archaeologist Eamonn Kelly, "sketchy and incomplete", the archaeological evidence suggests a complex and prosperous society that assimilated and adapted external cultural influences.[30] Numerous Iron Age carved stones survive, but only a small number are iconic or decorated, and they are mostly in the La Tène style, which reached Ireland c. 300 BC.[46]

Celtic stone heads

[edit]

The earliest European stone idol heads appeared in the Nordic countries in the late Bronze Age, where they continued to be produced, including in Iceland, until the end of the Viking Age in the 11th century AD. The very early examples resemble contemporary full-length wooden figures, and both types are assumed to have been created for cultic sites. However, early examples are rare; only around eight known pre-historic Nordic stone heads have been identified.[47] The type spread across Northern Europe, with the most numerous examples appearing in both the northeast and southeast of Gaul and across the British Isles in the Romano-British period (between 43 and 410 AD). Most scholars believe that the British and Irish heads were a combination of abstract Celtic art and the monumentalism of Roman sculpture.[23][48]

The early forms of Ancient Celtic religion were introduced to Ireland around 400 BC.[22] From surviving artefacts, it can be assumed that both multi-headed (as with the Corraghy head) or multi-faced idols were a common part of their iconography and represented all-knowing and all-seeing gods, symbolising the unity of the past, present and future.[49] According to the archaeologist Miranda Aldhouse-Green, the Corleck Head may have been used "to gain knowledge of places or events far away in time and space".[50]

Typically, they were utilised at larger cult or worship sites, of which the known examples are usually near holy wells or sacred groves.[30] The hole at its base indicates that it was once attached to a larger structure, perhaps a pillar comparable to the now lost six ft (1.8 m) wooden structure found in the 1790s in a bog near Aghadowey, County Londonderry, which was capped with a figure with four heads.[d]

Head cult

[edit]Representations of human heads are often found in Insular or Gaulish Celtic artefacts.[45] The archaeologist Ann Ross notes that in several early Insular vernacular accounts, the head was venerated by the Celts, who believed it "the seat of the soul, the centre of the vital essence" and assumed it had divine powers.[52] Classical Roman sources mention instances of Celts retaining the severed heads of their enemies as war trophies, claiming that they practised head-hunting and placed severed heads on stakes near their dwellings.[52] Other accounts indicate that the Celts believed that placing a severed head on a standing stone or pillar would bring it back to life.[53][54] These and later claims are circumstantially supported by Iron Age burial sites found to contain decapitated bodies or severed skulls.[45]

This has led to much speculation among archaeologists as to the existence of a Celtic head cult centred around, according to Kelly, a practice of "ritual and sacrifice", in which stone or wooden heads played a central idolatry role.[45] While the Roman and Insular accounts resemble others from contemporary Britain and mainland Europe, the Irish vernacular records were mostly set down by Christian monks who would have had, according to the folklorist Dáithí Ó hÓgáin, "theological reasons" to slant the oral traditions in an unfavourable light compared to their own beliefs and rituals. At the same time, the Romans dismissed the druids (the priestly caste in ancient Celtic cultures) as relatively primitive enemies.[22]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In addition, the late-19th-century tendency to associate objects with a mythical or a late-19th-century Celtic Revival viewpoint, based on medieval texts or contemporary romanticism, has been largely discredited.[26]

- ^ The others are Cathedral Hill in Armagh town, the Newtownhamilton and Tynan areas in Armagh County, the most southern part of Lough Erne in County Fermanagh, and the Raphoe region in north-west County Donegal.[31]

- ^ The townland of Ralaghan is located around 7 km (4.3 mi) south-east of Corleck Hill.[14] According to Barron, he was approached one day in a bog by a man holding a large stick-like object which turned out to be the Ralaghan Idol. The man told him that he intended to throw it back into the bog and that "we're getting dozens of these carved sticks and putting them back. You see, you can't take what's been offered ... the other day one of us got a beautiful bowl, bronze or gold ... carved and decorated all over." When Barron asked him where the bowl was now, he said they had thrown it back "at once, fearing bad luck to have kept it.[36]

- ^ The Aghadowey pillar was carved from a tree trunk and had four heads each with hair, that is today known only from a very simple 19th-century drawing annotated as a "Heathen image found in the bog of Ballybritoan Parish Aghadowey".[51]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Smyth (2012), p. 24

- ^ a b O'Toole, Fintan. "A history of Ireland in 100 objects: Corleck Head". The Irish Times, 25 June 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2022

- ^ Rynne (1972), pp. 79–93

- ^ a b c d e f Kelly (2002), p. 142

- ^ Cooney (2023), p. 349

- ^ Ross (1958), p. 13

- ^ a b c d Kelly (2002), p. 132

- ^ Ross (1958), pp. 13–14, 24

- ^ Waddell (1998), pp. 360, 371

- ^ Kelly (2002), pp. 132, 142

- ^ a b c Rynne (1972), p. 84

- ^ Ross (1958), p. 22

- ^ a b c Waddell (1998), p. 362

- ^ a b c Waddell (1998), p. 360

- ^ a b Paterson (1962), p. 82

- ^ a b "Thomas J. Barron. Cavan County Libraries. Retrieved 3 March 2024

- ^ a b c Duffy (2012), p. 153

- ^ Smyth (2012), p. 25

- ^ Barron (1976), pp. 98–99

- ^ a b c d Waddell (2023), p. 320

- ^ a b Waddell (1998), p. 371

- ^ a b c Ó Hogain (2000), p. 20

- ^ a b c d e Smyth (2023), The History

- ^ Ross (2010), pp. 65–66

- ^ Smyth (2012), p. 88

- ^ a b Gleeson (2022), p. 20

- ^ Rynne (1972), p. 79

- ^ Ross (1958), p. 14

- ^ Morahan (1987–1988), p. 149

- ^ a b c Kelly (1984), p. 10

- ^ a b Rynne (1972), p. 80

- ^ Waddell (2023), p. 321

- ^ Rynne (1972), plate X

- ^ Warner (2003), pp. 24–25

- ^ Warner (2003), p. 24

- ^ a b c Ross (2010), p. 65

- ^ a b Barron (1976), p. 100

- ^ Ross (1998), p. 200

- ^ MacKillop (2004), p. 104

- ^ Smyth (2023), The Latin Style

- ^ Ross (2010), p. 111

- ^ Smyth (2023), The Human Head

- ^ Rynne (1972), p. 78

- ^ Warner (2003), p. 27

- ^ a b c d "A Face From The Past: A possible Iron Age anthropomorphic stone carving from Trabolgan, Co. Cork". National Museum of Ireland. Retrieved 22 April 2023

- ^ Kelly (1984), pp. 7, 9

- ^ Zachrisson (2017), p. 355

- ^ Zachrisson (2017), pp. 359—360

- ^ Ó Hogain (2000), p. 23

- ^ Aldhouse-Green (2015), "The Seeing Stone of Corleck"

- ^ Waddell (1998), pp. 361, 374

- ^ a b Ross (1958), p. 11

- ^ Ross (1967), pp. 147, 159

- ^ Zachrisson (2017), p. 359

Sources

[edit]- Aldhouse-Green, Miranda. The Celtic Myths: A Guide to the Ancient Gods and Legends. London: Thames and Hudson, 2015. ISBN 978-0-5002-5209-3

- Barron, Thomas J. "Some Beehive Quernstones from Counties Cavan and Monaghan". Clogher Record, volume 9, No. 1, 1976. JSTOR 27695733 doi:10.2307/27695733

- Cooney, Gabriel. Death in Irish prehistory. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 2023. ISBN 978-1-8020-5009-7

- Duffy, Patrick. "Reviewed Work: Landholding, Society and Settlement In Ireland: a historical geographer's perspective by T. Jones Hughes". Clogher Record, volume 21, no. 1, 2012. JSTOR 41917586

- Gleeson, Patrick. "Reframing the first millennium AD in Ireland: archaeology, history, landscape". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 2022

- Kelly, Eamonn. "The Iron Age". In Ó Floinn, Raghnall; Wallace, Patrick (eds). Treasures of the National Museum of Ireland: Irish Antiquities. Dublin: National Museum of Ireland, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7171-2829-7

- Kelly, Eamonn. "The Archaeology of Ireland 3: The Pagan Celts". Ireland Today, no. 1006, 1984

- Kelly, Eamonn. "Late Bronze Age and Iron Age Antiquities". In: Ryan, Micheal (ed). Treasures of Ireland: Irish Art 3000 BC – 1500 AD. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1983. ISBN 978-0-9017-1428-2

- Lanigan Wood, Helen. "Dogs and Celtic Deities: Pre-Christian Stone Carvings in Armagh". Irish Arts Review Yearbook, volume 16, 2000. JSTOR 20493105

- MacKillop, James. A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-1986-0967-4

- Morahan, Leo. "A Stone Head from Killeen, Belcarra, Co. Mayo". Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society, volume 41, 1987–1988. JSTOR 25535584

- Ó Hogain, Dáithí. "Patronage & Devotion in Ancient Irish Religion". History Ireland, volume 8, no. 4, winter 2000. JSTOR 27724824

- Paterson, T.G.F. "Carved Head from Cortynan, Co. Armagh". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, volume 92, no. 1, 1962. JSTOR 25509461

- "Report of the Council for 1937". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Seventh Series, volume 8, no. 1, 30 June 1938. JSTOR 25510127

- Ross, Anne. The Pagan Celts. Denbighshire: John Jones, 1998. ISBN 978-1-8710-8361-3

- Ross, Anne. Druids: Preachers of Immortality. Cheltenham: The History Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-7524-1433-1

- Ross, Anne. "A Celtic Three-faced Head from Wiltshire". Antiquity volume 41, 1967

- Ross, Anne. "The Human Head in Insular Pagan Celtic Religion". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, volume 91, 1958

- Rynne, Etienn. "Celtic Stone Idols in Ireland". In: Thomas, Charles. The Iron Age in the Irish Sea province: papers given at a C.B.A. conference held at Cardiff, January 3 to 5, 1969. London: Council for British Archaeology, 1972

- Rynne, Etienn. "The Three Stone Heads at Woodlands, near Raphoe, Co. Donegal". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, volume 94, no. 2, 1964. JSTOR 25509564

- Smyth, Jonathan. "The Corleck Head and other aspects of east Cavan's ancient past". Cavan County Libraries, 25 May 2023.

- Smyth, Jonathan. Gentleman and Scholar: Thomas James Barron, 1903 – 1992. Cumann Seanchais Bhreifne, 2012. ISBN 978-0-9534-9937-3

- Waddell, John. Pagan Ireland: Ritual and Belief in Another World. Dublin: Wordwell Books, 2023. ISBN 978-1-9167-4202-4

- Waddell, John. The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland. Galway: Galway University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-1-8698-5739-4

- Warner, Richard. "Two pagan idols – remarkable new discoveries". Archaeology Ireland, volume 17, no. 1, 2003

- Zachrisson, Torun. "The Enigmatic Stone Faces: Cult Images from the Iron Age?". In Semple, Sarah; Orsini, Celia; Mui, Sian (eds). Life on the Edge: Social, Political and Religious Frontiers in Early Medieval Europe. Hanover: Hanover Museum, 2017. ISBN 978-3-9320-3077-2

External links

[edit]- The Corleck Head and other aspects of east Cavan's ancient past. Video lecture by Jonathan Smyth, Cavan Library, 2023