Houthi movement

The Houthi movement (/ˈhuːθi/; Arabic: الحوثيون al-Ḥūthiyūn [al.ħuː.θi.juːn]), officially known as Ansar Allah[a] (أنصار الله ʾAnṣār Allāh, lit. 'Supporters of God'), is a Shia Islamist political and military organization that emerged from Yemen in the 1990s. It is predominantly made up of Zaidi Shias, with their namesake leadership being drawn largely from the Houthi tribe.[91]

Under the leadership of Zaidi religious leader Hussein al-Houthi, the Houthis emerged as an opposition movement to Yemen President Ali Abdullah Saleh, whom they accused of corruption and being backed by Saudi Arabia and the United States.[92][93] In 2003, influenced by the Lebanese Shia political and military organization Hezbollah, the Houthis adopted their official slogan against the United States, Israel, and the Jews.[94] Al-Houthi resisted Saleh's order for his arrest, and was afterwards killed by the Yemeni military in Saada in 2004, sparking the Houthi insurgency.[95][96] Since then, the movement has been mostly led by his brother Abdul-Malik al-Houthi.[95]

The organization took part in the Yemeni Revolution of 2011 by participating in street protests and coordinating with other Yemeni opposition groups. They joined Yemen's National Dialogue Conference but later rejected the 2011 reconciliation deal.[14][97] In late 2014, the Houthis repaired their relationship with Saleh, and with his help they took control of the capital city. The takeover prompted a Saudi-led military intervention to restore the internationally recognized government, leading to an ongoing civil war which included missile and drone attacks against Saudi Arabia and its ally United Arab Emirates.[98][99][100] Following the outbreak of the 2023 Israel–Hamas war, the Houthis began to fire missiles at Israel and to attack ships off Yemen's coast in the Red Sea, which they say is in solidarity with the Palestinians and aiming to facilitate entry of humanitarian aid into the Gaza Strip.[101][102]

The Houthi movement attracts followers in Yemen by portraying themselves as fighting for economic development and the end of the political marginalization of Zaidi Shias,[97] as well as by promoting regional political–religious issues in its media. The Houthis have a complex relationship with Yemen's Sunnis; the movement has discriminated against Sunnis but has also allied with and recruited them.[103][104][14] The Houthis aim to govern all of Yemen and support external movements against the United States, Israel, and Saudi Arabia.[105] Because of the Houthis' ideological background, the conflict in Yemen is widely seen as a front of the Iran–Saudi Arabia proxy war.[106]

History

According to Ahmed Addaghashi, a professor at Sanaa University, the Houthis began as a moderate theological movement that preached tolerance and held a broad-minded view of all the Yemeni peoples.[107] Their first organization, "the Believing Youth" (BY), was founded in 1992 in Saada Governorate[108]: 1008 by either Mohammed al-Houthi,[109]: 98 or his brother Hussein al-Houthi.[110]

The Believing Youth established school clubs and summer camps[109]: 98 in order to "promote a Zaidi revival" in Saada.[110] By 1994–95, between 15,000 and 20,000 students had attended BY summer camps. The religious material included lectures by Mohammed Hussein Fadhlallah (a Lebanese Shia scholar) and Hassan Nasrallah (Secretary General of Hezbollah).[109]: 99 [111]

The formation of the Houthi organisations has been described by Adam Baron of the European Council on Foreign Relations as a reaction to foreign intervention. Their views include shoring up Zaydi support against the perceived threat of Saudi-influenced ideologies in Yemen and a general condemnation of the former Yemeni government's alliance with the United States, which, along with complaints regarding the government's corruption and the marginalisation of much of the Houthis' home areas in Saada, constituted the group's key grievances.[112]

Although Hussein al-Houthi, who was killed in 2004, had no official relation with Believing Youth (BY), according to Zaid, he contributed to the radicalisation of some Zaydis after the 2003 invasion of Iraq. BY-affiliated youth adopted anti-American and anti-Jewish slogans, which they chanted in the Al Saleh Mosque in Sanaa after Friday prayers. According to Zaid, the followers of Houthi's insistence on chanting the slogans attracted the authorities' attention, further increasing government worries over the extent of the Houthi movement's influence. "The security authorities thought that if today the Houthis chanted 'Death to America', tomorrow they could be chanting 'Death to the president [of Yemen]'".[citation needed]

In 2004, 800 BY supporters were arrested in Sanaa. President Ali Abdullah Saleh then invited Hussein al-Houthi to a meeting in Sanaa, but Hussein declined. On 18 June, Saleh sent government forces to arrest Hussein.[113] Hussein responded by launching an insurgency against the central government but was killed on 10 September.[114] The insurgency continued intermittently until a ceasefire agreement was reached in 2010.[107] During this prolonged conflict, the Yemeni army and air force were used to suppress the Houthi rebellion in northern Yemen. The Saudis joined these anti-Houthi campaigns, but the Houthis won against both Saleh and the Saudi army. According to the Brookings Institution, this particularly humiliated the Saudis, who spent tens of billions of dollars on their military.[60]

The Houthis participated in the 2011 Yemeni Revolution, as well as the ensuing National Dialogue Conference (NDC).[115] However, they rejected the provisions of the November 2011 Gulf Cooperation Council deal on the ground that "it divide[d] Yemen into poor and wealthy regions" and also in response to assassination of their representative at NDC.[116][117]

As the revolution went on, Houthis gained control of greater territory. By 9 November 2011, Houthis were said to be in control of two Yemeni governorates (Saada and Al Jawf) and close to taking over a third governorate (Hajjah),[118] which would enable them to launch a direct assault on the Yemeni capital of Sanaa.[119] In May 2012, it was reported that the Houthis controlled a majority of Saada, Al Jawf, and Hajjah governorates; they had also gained access to the Red Sea and started erecting barricades north of Sanaa in preparation for more conflict.[120]

By September 2014, Houthis were said to control parts of the Yemeni capital, Sanaa, including government buildings and a radio station.[121] While Houthi control expanded to the rest of Sanaa, as well as other towns such as Rada', this control was strongly challenged by Al-Qaeda. The Gulf States believed that the Houthis had accepted aid from Iran while Saudi Arabia was aiding their Yemeni rivals.[122]

On 20 January 2015, Houthi rebels seized the presidential palace in the capital. President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi was in the presidential palace during the takeover but was not harmed.[123] The movement officially took control of the Yemeni government on 6 February, dissolving parliament and declaring its Revolutionary Committee to be the acting authority in Yemen.[99] On 20 March the al-Badr and al-Hashoosh mosques came under suicide attack during midday prayers, and the Islamic State quickly claimed responsibility. The blasts killed 142 Houthi worshippers and wounded more than 351, making it the deadliest terrorist attack in Yemen's history.[124]

On 27 March 2015, in response to perceived Houthi threats to Sunni factions in the region, Saudi Arabia along with Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, UAE, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Sudan led a gulf coalition airstrike in Yemen.[125] The military coalition included the United States which helped in planning of airstrikes, as well as logistical and intelligence support.[126] The US Navy has actively participated in the Saudi-led naval blockade of Houthi-controlled territory in Yemen,[127] which humanitarian organizations argue has been the main contributing factor to the outbreak of famine in Yemen.[128]

According to a 2015 September report by Esquire magazine, the Houthis, once the outliers, are now one of the most stable and organised social and political movements in Yemen. The power vacuum created by Yemen's uncertain transitional period has drawn more supporters to the Houthis. Many of the formerly powerful parties, now disorganised with an unclear vision, have fallen out of favour with the public, making the Houthis—under their newly branded Ansar Allah name—all the more attractive.[18]

Houthi spokesperson Mohamed Abdel Salam stated that his group had spotted messages between the UAE and Saleh three months before his death. He told Al-Jazeera that there was communication between Saleh, UAE and a number of other countries such as Russia and Jordan through encrypted messages.[129] The alliance between Saleh and the Houthi broke down in late 2017,[130] with armed clashes occurring in Sanaa from 28 November.[131] Saleh declared the split in a televised statement on 2 December, calling on his supporters to take back the country[132] and expressed openness to a dialogue with the Saudi-led coalition.[130] On 4 December 2017, Saleh's house in Sanaa was assaulted by fighters of the Houthi movement, according to residents.[133] Saleh was killed by the Houthis on the same day.[134][135]

In January 2021, the United States designated the Houthis a terrorist organization, creating fears of an aid shortage in Yemen,[136] but this stance was reversed a month later after Joe Biden became president.[137] On 17 January 2022, Houthi missile and drone attacks on UAE industrial targets set fuel trucks on fire and killed three foreign workers. This was the first specific attack to which the Houthi admitted, and the first to result in deaths.[138] A response led by Saudi Arabia included a 21 January air strike on a detention centre in Yemen, resulting in at least 70 deaths.[139]

Following the outbreak of the 2023 Israel–Hamas war, the Houthis began to fire missiles at Israel and to attack ships off Yemen's coast in the Red Sea, which they say is in solidarity with the Palestinians and aiming to facilitate entry of humanitarian aid into the Gaza Strip.[101][140][102] On 31 October Houthi forces launched ballistic missiles at Israel, which were shot down by Israel's Arrow missile defense system. Israeli officials claimed that this was the first ever combat to occur in space.[141] In order to end the attacks in the Red Sea,[142] the Houthis demanded a ceasefire in Gaza and an end to Israel's blockade of the Gaza Strip.[143] In January 2024, the United States and the United Kingdom conducted airstrikes against multiple Houthi targets in Yemen.[144]

Membership and ranks

There is a difference between the al-Houthi family[109]: 102 and the Houthi movement. The movement was called by their opponents and foreign media "Houthis". The name came from the surname of the early leader of the movement, Hussein al-Houthi, who died in 2004.[145]

Membership of the group had between 1,000 and 3,000 fighters as of 2005[146] and between 2,000 and 10,000 fighters as of 2009.[147] In 2010, the Yemen Post claimed that they had over 100,000 fighters.[148] According to Houthi expert Ahmed Al-Bahri, by 2010, the Houthis had a total of 100,000–120,000 followers, including both armed fighters and unarmed loyalists.[149] As of 2015, the group is reported to have attracted new supporters from outside their traditional demographics.[112][150]

Ideology

The Houthi movement follows a mixed ideology with religious, Yemeni nationalist, and big tent populist tenets, imitating Hezbollah. Outsiders have argued that their political views are often vague and contradictory and that many of their slogans do not accurately reflect their aims.[10][11][151] According to researcher Bernard Haykel, the movement's founder Hussein al-Houthi was influenced by a variety of different religious traditions and political ideologies, making it difficult to fit him or his followers into existing categories.[152] The Houthis have portrayed themselves as national resistance, defending all Yemenis from outside aggression and influences, as champions against corruption, chaos, and extremism, and as representative for the interests of marginalized tribal groups and the Zayidi sect.[10][11][151]

Haykel argues that the Houthi movement has two central religious-ideological tenets. The first is the "Quranic Way", and which encompasses the belief that the Quran does not allow for interpretation and contains everything needed to improve Muslim society. The second is the belief in the absolute, divine right of Ahl al-Bayt (Prophet's descendants) to rule,[153] a belief attributed to Jaroudism, a fundamentalist offshoot of Zaydism.[154]

The group has also exploited the popular discontent over corruption and reduction of government subsidies.[14][27] According to a February 2015 Newsweek report, Houthis are fighting "for things that all Yemenis crave: government accountability, the end to corruption, regular utilities, fair fuel prices, job opportunities for ordinary Yemenis and the end of Western influence".[155] In forging alliances, the Houthi movement has been opportunistic, at times allying with countries it later declared its enemy such as the United States.[11]

Religion

In general, the Houthi movement has centered its belief system on the Zaydi branch of Islam,[10][b] a sect of Islam almost exclusively present in Yemen.[156] Zaydis make up about 25 percent of the population, Sunnis make up 75 percent. Zaydi-led governments ruled Yemen for 1,000 years up until 1962.[113] Since its foundation, the Houthi movement has often acted as advocates for Zaydi revivalism in Yemen.[27][159]

Although they have framed their struggle in religious terms and put great importance in their Zaydi roots, the Houthis are not an exclusively Zaydi group. In fact, they have rejected their portrayal by others as a faction which is purportedly only interested in Zaydi-related issues. They have not publicly advocated for the restoration of the old Zaydi imamate,[10] although analysts have argued that they might plan to restore it in the future.[14][154] Most Yemenis have a low opinion of the old imamate, and Hussein al-Houthi also did not advocate the imamate's restoration. Instead, he proposed a "Guiding Eminence" (alam al-huda), an individual descended from the Prophet who would act as a "universal leader for the world", though never defined this position's prerogatives or how they should be appointed.[162]

The movement has also recruited and allied with Sunni Muslims;[163][10][103][14][151] according to researcher Ahmed Nagi, several themes of the Houthi ideology "such as Muslim unity, prophetic lineages, and opposition to corruption [...] allowed the Houthis to mobilize not only northern Zaydis, but also inhabitants of predominantly Shafi'i areas."[14] However, the group is known to have discriminated against Sunni Muslims as well, closing Sunni mosques and primarily placing Zaydis in leadership positions in Houthi-controlled areas.[10][103][104][14][151] The Houthis lost significant support among Sunni tribes after killing ex-President Saleh.[164]

Many Zaydis also oppose the Houthis, regarding them as Iranian proxies and the Houthis' form of Zaydi revivalism an attempt to "establish Shiite rule in the north of Yemen".[157] In addition, Haykel argued that the Houthis follow a "a highly politicised, revolutionary, and intentionally simplistic, even primitivist interpretation of [Zaydism]'s teachings". Their view of Islam is largely based on the teachings of Hussein al-Houthi, collected after his death in a book titled Malazim (Fascicles), a work treated by Houthis as more important than older Zaydi theological traditions, resulting in repeated disputes with established Zaydi religious leaders.[165]

The Malazim reflect a number of different religious and ideological influences, including by Khomeinism and revolutionary Sunni Islamist movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood. Hussein al-Houthi believed that the "last exemplary" Zaydi scholar and leader was Al-Hadi ila'l-Haqq Yahya; later Zaydi imams were regarded as having deviated from the original form of Islam.[152] The Houthis' belief in the "Quranic Way" also includes the rejection of tafsir (Quranic interpretations) as being derivative and divisive, meaning that they have a low opinion of most existing Islamic theological and juridical schools,[153] including Zaydi traditionalists based in Sanaa with whom they often clash.[166]

The Houthis claim that their actions are to fight against the alleged expansion of Salafism in Yemen, and for the defence of their community from discrimination.[157][14][167] In the years before the rise of the Houthi movement, state-supported Salafis had harassed Zaydis and destroyed Zaydi sites in Yemen.[168] After their rise to power in 2014, the Houthis consequently "crushed" the Salafi community in Saada Governorate[168] and mostly eliminated the al-Qaeda presence in the areas under their control;[167] the Houthis view al-Qaeda as "Salafi jihadists" and thus "mortal enemies".[169] On the other side, between 2014 and 2019, the Houthi leadership have signed multiple co-existence agreements with the Salafi community; pursuing Shia-Salafi reconciliation.[170] The Yemeni government has often accused the Houthis of collaborating with al-Qaeda to undermine its control of southern Yemen.[80][171]

Governance

In general, the Houthis' political ideology has gradually shifted from "heavily-religious mobilisation and activism under Husayn to the more assertive and statesmanlike rhetoric under Abdulmalik", its current leader.[159] With strong support received by Houthis from the predominantly Zaydi northern tribes, the Houthi movement has often been described as tribalist or monarchist faction in opposition to republicanism.[11][154] Regardless, they have managed to rally many people outside of their traditional bases to their cause, and became a major nationalist force.[11]

When armed conflict for the first time erupted back in 2004 between the Yemeni government and Houthis, the President Ali Abdullah Saleh accused the Houthis and other Islamic opposition parties of trying to overthrow the government and the republican system. However, Houthi leaders, for their part, rejected the accusation by saying that they had never rejected the president or the republican system, but were only defending themselves against government attacks on their community.[172] After their takeover of northern Yemen in 2014, the Houthis remained committed to republicanism and continued to celebrate republican holidays.[162] The Houthis have an ambivalent stance on the possible transformation of Yemen into a federation or the separation into two fully independent countries to solve the country's crisis. Though not opposed to these plans per se, they have declined any plans which would in their eyes marginalize the northern tribes politically.[10][14]

Meanwhile, their opponents have asserted that the Houthis desire to institute Zaydi religious law,[173] destabilising the government and stirring anti-American sentiment.[174] In contrast, Hassan al-Homran, a former Houthi spokesperson, has said that "Ansar Allah supports the establishment of a civil state in Yemen. We want to build a striving modern democracy. Our goals are to fulfil our people's democratic aspirations in keeping with the Arab Spring movement."[175] In an interview with Yemen Times, Hussein al-Bukhari, a Houthi insider, said that Houthis' preferable political system is a republic with elections where women can also hold political positions, and that they do not seek to form a cleric-led government after the model of Islamic Republic of Iran, for "we cannot apply this system in Yemen because the followers of the Shafi (Sunni) doctrine are bigger in number than the Zaydis".[176] In 2018, the Houthi leadership proposed the establishment of a non-partisan transitional government composed of technocrats.[177]

Ali Akbar Velayati, International Affairs Advisor to Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, stated in October 2014 that "We are hopeful that Ansar-Allah has the same role in Yemen as Hezbollah has in eradicating the terrorists in Lebanon".[178] Mohammed Ali al-Houthi criticized the Trump-brokered Abraham Accords between Israel and the United Arab Emirates as "betrayal" against the Palestinians and the cause of pan-Arabism.[179]

Women's rights and freedom of expression

The Houthis' treatment of women and their restrictions on the arts has been subject of debate. On one side, the movement has stated that it defends women's rights to vote and take public offices,[176] and some feminists have fled from government-held areas into Houthi territories as the latter at least disempower more radical jihadists.[167] The Houthis field their own women security force[104] and have a Girl Scouts wing.[167] However, it has been also been reported that Houthis harass women and restrict their freedoms of movement and expression.[154][104]

In regards to culture, the Houthis try to spread their views through propaganda[167] using mainstream media, social media, and poetry as well as the "Houthification" of the education system to "instil Huthi values and mobilise the youth to join the fight against the coalition forces".[159] However, the Houthis have been inconsistent in regards how to deal with forms of artistic expression which they disapprove of. The movement has allowed radio stations to continue broadcast music and content which the Houthis view as too Western,[167] but also banned certain songs and harassed artists such as wedding musicians. In one instance which generated much publicity, Houthi policemen conditioned that music could be played at a wedding party if it was not broadcast by loadspeakers. When the party guests did not conform to this demand, the main wedding singer was arrested.[180] Journalist Robert F. Worth stated that "many secular-minded Yemenis seem unsure whether to view the Houthis as oppressors or potential allies." In general, the Houthis' policies are often decided on a local basis, and high-ranking Houthi officials are often incapable of checking regional officers' powers, making the treatment of civilians dependent on the area.[167]

Slogan and controversies

The group's slogan reads as following: "God Is Great, Death to America, Death to Israel, Curse on the Jews, Victory to Islam".[181] This motto is partially modelled on the motto of revolutionary Iran, which reads "Death to U.S., and death to Israel".[182]

Some Houthi supporters stress that their ire for the U.S. and Israel is directed toward the governments of America and Israel. Ali al-Bukhayti, the spokesperson and official media face of the Houthis, rejected the literal interpretation of the slogan by stating in one of his interviews that "We do not really want death to anyone. The slogan is simply against the interference of those governments [i. e., U.S. and Israel]".[183] In the Arabic Houthi-affiliated TV and radio stations they use religious connotations associated with jihad against Israel and the US.[94]

Persecution of the Yemenite Jewish community

The Houthis have been accused of expelling or restricting members of the rural Yemeni Jewish community, which had about 50 remaining members.[184] Reports of abuse include Houthi supporters bullying or attacking the country's Jews.[185][186] Houthi officials have denied any involvement in the harassment, asserting that under Houthi control, Jews in Yemen would be able to live and operate freely as any other Yemeni citizen. "Our problems are with Zionism and the occupation of Palestine, but Jews here have nothing to fear", said Fadl Abu Taleb, a spokesman for the Houthis.[186]

Despite insistence by Houthi leaders that the movement is not sectarian, a Yemeni Jewish rabbi has reportedly said that many Jews remain terrified by the movement's slogan.[186] As a result, Yemeni Jews reportedly retain a negative sentiment towards the Houthis, who they allege have committed persecutions against them.[21] According to Israeli Druze politician Ayoob Kara, Houthi militants had given an ultimatum telling Jews to "convert to Islam or leave Yemen".[187]

In March 2016, a UAE-based newspaper reported that one of the Yemeni Jews, who emigrated to Israel in 2016, was fighting with the Houthis. In the same month a Kuwaiti newspaper, al-Watan, reported that a Yemeni Jew named Haroun al-Bouhi was killed in Najran while fighting with the Houthis against Saudi Arabia. The Kuwaiti newspaper added that the Yemeni Jews had a good relationship with Ali Abdullah Salah, who was at that time allied with the Houthis and were fighting in different fronts with the Houthis.[188][189]

Al-Houthi has said through his fascicles: "Arab countries and all Islamic countries will not be safe from Jews except through their eradication and the elimination of their entity."[190] A New York Times journalist reported being asked why they were speaking to a "dirty Jew" and that the Jews in the village were unable to communicate with their neighbors.[191]

Persecution of the Baháʼí community

The Houthis have been accused of detaining, torturing, arresting, and holding incommunicado Baháʼí Faith members on charges of espionage and apostasy, which are punishable by death.[192][193] Houthi leader Abdel-Malek al-Houthi has targeted Baháʼís in public speeches, and accused the followers of Baháʼí Faith of being "satanic"[194] and agents for the western countries, citing a 2013 fatwa issued by Iran's supreme leader.[192]

Leaders

- Hussein Badreddin al-Houthi – former leader (killed 2004)

- Abdul-Malik Badreddin al-Houthi – leader

- Yahia Badreddin al-Houthi – senior leader

- Abdul-Karim Badreddin al-Houthi – high-ranking commander

- Badr Eddin al-Houthi – spiritual leader (died 2010)

- Abdullah al-Ruzami – former military commander

- Abu Ali Abdullah al-Hakem al-Houthi – military commander

- Saleh Habra – political leader[195]

- Fares Mana'a – Houthi-appointed governor of Sa'dah,[196] and former head of Saleh's presidential committee[197]

Activism and tactics

Political

During their campaigns against both the Saleh and Hadi governments, Houthis used civil disobedience. Following the Yemeni government's decision on 13 July 2014 to increase fuel prices, Houthi leaders succeeded in organising massive rallies in the capital Sanaa to protest the decision and to demand resignation of the incumbent government of Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi for "state-corruption".[198] These protests developed into the 2014–2015 phase of the insurgency. Similarly, following 2015 Saudi-led airstrikes against Houthis which claimed civilians lives, Yemenis responded to the Abdul-Malik al-Houthi's call and took to streets of the capital, Sanaa, in tens of thousands to voice their anger at the Saudi invasion.[199]

The movement's expressed goals include combating economic underdevelopment and political marginalization in Yemen while seeking greater autonomy for Houthi-majority regions of the country.[97] One of its spokesperson Mohammed al-Houthi claimed in 2018 that he supports a democratic republic in Yemen.[60][177] The Houthis have made fighting corruption the centerpiece of their political program.[60]

Cultural

The Houthis have also held a number of mass gatherings since the revolution. On 24 January 2013, thousands gathered in Dahiyan, Sa'dah and Heziez, just outside Sanaa, to celebrate Mawlid al-Nabi, the birth of Mohammed. A similar event took place on 13 January 2014 at the main sports' stadium in Sanaa. On this occasion, men and women were completely segregated: men filled the open-air stadium and football field in the centre, guided by appointed Houthi safety officials wearing bright vests and matching hats; women poured into the adjacent indoor stadium, led inside by security women distinguishable only by their purple sashes and matching hats. The indoor stadium held at least five thousand women—ten times as many attendees as the 2013 gathering.[18]

Media

The Houthis are said to have "a huge and well-oiled propaganda machine". They have established "a formidable media arm" with the Lebanese Hezbollah's technical support. The format and content of the group's leader, Abdul-Malik al-Houthi's televised speeches are said to have been modeled after those of Hezbollah's Secretary General, Hassan Nasrallah. Following the peaceful youth uprising in 2011, the group launched its official TV channel, Almasirah. "The most impressive part" of Houthi propaganda, though, is their media print which includes 25 print and electronic publications.[94]

One of the most versatile form of Houthi mass media are the zawamil,[200] a genre of primarily tribal oral poetry embedded in Yemen's social fabric. The zamil, rooted in cultural tradition, has been weaponised by the Houthis as a tool of propaganda and remains one of the most popular and rapidly growing platforms of Houthi propaganda,[201][202] sung by popular vocalists like Issa Al-Laith and disseminated through various social media platforms including YouTube, Twitter and Telegram.[203][204] The Spectator describes Houthi zawamil as its most successful part of their propaganda, stressing the movement's supposed piety, bravery and poverty in comparison with the corruption, wealth and hypocrisy of their adversaries, the Saudi-led coalition, and Arab states allied to Israel.[205]

Houthis also utilize radios as an effective means of spreading influence, storming radio stations and confiscating equipment of radio stations that do not adhere to what they're allowed to broadcast by the Houthis.[206] A Houthi fundraising campaign through a radio station affiliated with Iran-backed Houthi rebels has collected 73.5 million Yemeni rials ($132,000) for the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah.[207]

Another western-based media, "Uprising Today", is also known to be extensively pro-Houthi.[208]

Military

In 2009, U.S. Embassy sources have reported that Houthis used increasingly more sophisticated tactics and strategies in their conflict with the government as they gained more experience, and that they fought with religious fervor.[209]

Armed strength

Late in 2015, Houthis announced the local production of short-range ballistic missile Qaher-1 on Al-Masirah TV. On 19 May 2017 Saudi Arabia intercepted a Houthi-fired ballistic missile targeting a deserted area south of the Saudi capital and most populous city Riyadh. The Houthi militias have captured dozens of tanks and masses of heavy weaponry from the Yemeni Armed Forces.[210][211][212]

In June 2019, the Saudi-led coalition stated that the Houthis had launched 226 ballistic missiles during the insurgency so far.[213]

The 2019 Abqaiq–Khurais attack targeted the Saudi Aramco oil processing facilities at Abqaiq and Khurais in eastern Saudi Arabia on 14 September 2019. The Houthi movement claimed responsibility, though the United States has asserted that Iran was behind the attack. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani said that "Yemeni people are exercising their legitimate right of defence ... the attacks were a reciprocal response to aggression against Yemen for years."[214]

Naval warfare capabilities

In course of the Yemeni Civil War, the Houthis developed tactics to combat their opponents' navies. At first, their anti-ship operations were unsophisticated and limited to rocket-propelled grenades being shot at vessels close to the shore.[215] In the fight to secure the port city of Aden in 2015, the Yemeni Navy was largely destroyed, including all missile-carrying vessels. A number of smaller patrol craft, landing craft, and Mi-14 and Ka-28 ASW helicopters did survive. Their existence under Houthi control would be brief, as the majority of them were destroyed in air attacks during the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen in 2015. As a result, the Houthis were left with AShMs (anti-ship missiles) stored ashore, but no launchers, and a smattering of small patrol ships. These, along with a number of locally manufactured small craft and miscellaneous vessels, were to form the foundation of the new naval warfare capabilities.[215][216]

Soon after the Houthis took over Yemen in 2015, Iran sought to strengthen the Houthis' naval capabilities, allowing the Houthis, and thus Iran, to intercept Coalition shipping off the Red Sea coast, by providing additional AShMs and constructing truck-based launchers that could easily be hidden after a launch. Iran also anchored the Saviz intelligence vessel, disguised as a regular cargo vessel, off the coast of Eritrea, that provided intelligence and updates on Coalition ship movements to the Houthis.[217] The Saviz served in this capacity until it was damaged in an Israeli limpet mine attack in April 2021, when it was replaced by the Behshad.[218] The Behshad, like the Saviz, is based on a cargo ship.[219]

Meanwhile, in Yemen, the Houthis, presumably with the assistance of Iranian engineers, converted a number of 10-meter-long patrol craft donated by the UAE to the Yemeni Coast Guard in the early 2010s into WBIEDs (water born improvised explosive devices). In 2017, one of these was used to attack the Saudi frigate Al Madinah.[220] In the years since, three more WBIED designs have been built: the Tawfan-1, Tawfan-2, and Tawfan-3. 15 different types of naval mines were also produced.[221] These are being increasingly deployed in the Red Sea, but have yet to be successful against naval vessels.[222] The delivery of 120 km-ranged Noor and 200 km-ranged Qader AShMs, 300 km-ranged Khalij Fars ASBMs, and Fajr-4CL and "Al-Bahr Al-Ahmar" anti-ship rockets by Iran, which were unveiled during a 2022 Houthi parade, was arguably the most significant escalation in support. They combine long range, low cost, and high mobility with various types of guidance to create a weapon well-suited to the Houthi Navy.[223]

Though the Houthis' ASBM arsenal has yet to be tested, the Houthi Navy has had notable success with AShMs.[224] On October 1, 2016, it was able to hit the UAE Navy's HSV-2 Swift hybrid catamaran with a single C-801/C-802 AShM fired from a shore battery.[225] Although the ship managed to stay afloat, the damage was so severe that it had to be decommissioned.[225] The US Navy then sent two destroyers and an amphibious transport dock to the area to ensure that shipping could continue unabated. These vessels were then attacked with AShMs on three separate occasions, with no success.[226]

Though these attacks demonstrated the Houthis' limited ability to threaten vessels in Yemen's surrounding seas, the threat posed by them has since evolved significantly.[224] Armed with a variety of anti-ship ballistic missiles and rockets that can be notoriously difficult to intercept and cover large areas, the next round of maritime clashes with the navies of the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and the United States could have a completely different outcome.[224] The Houthis have also hinted at using their extensive arsenal of loitering munitions against commercial shipping in the Red Sea, a tactic similar to recent Iranian tactics in the Persian Gulf.[227]

Patrol boats were fitted with anti-tank guided missiles, about 30 coast-watcher stations were set up, disguised "spy dhows" were constructed, and the maritime radar of docked ships used to create targeting solutions for attacks.[216] One of the most notable features of the Houthis' naval arsenal became its remote-controlled drone boats which carry explosives and ram enemy warships.[215][222][224] Among these, the self-guiding Shark-33 explosive drone boats originated as patrol boats of the old Yemeni coast guard.[222] In addition, the Houthis have begun to train combat divers on the Zuqar and Bawardi islands.[216]

Alleged Iranian, North Korean and Russian support

Former Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh had accused the Houthis of having ties to external backers, in particular the Iranian government; Saleh stated in an interview with The New York Times,

The real reason they received unofficial support from Iran was because they repeat same slogan that is raised by Iran – death to America, death to Israel. We have another source for such accusations. The Iranian media repeats statements of support for these [Houthi] elements. They are all trying to take revenge against the USA on Yemeni territories.[228]

Such backing has been reported by diplomatic correspondents of major news outlets (e.g., Patrick Wintour of The Guardian), and has been the reported perspective of Yemeni governmental leaders militarily and politically opposing Houthi efforts (e.g., as of 2017, the UN-recognized, deposed Yemeni President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi, who referred to the "Houthi rebels... as 'Iranian militias'".[229][230]

The Houthis in turn accused the Saleh government of being backed by Saudi Arabia and of using Al-Qaeda to repress them.[231] Under the next President Hadi, Gulf Arab states accused Iran of backing the Houthis financially and militarily, though Iran denied this, and they were themselves backers of President Hadi.[232] Despite confirming statements by Iranian and Yemeni officials in regards to Iranian support in the form of trainers, weaponry, and money, the Houthis denied reception of substantial financial or arm support from Iran.[27][233] Joost Hiltermann of Foreign Policy wrote that whatever little material support the Houthis may have received from Iran, the intelligence and military support by US and UK for the Saudi Arabian-led coalition exceed that by many factors.[234]

In April 2015, the United States National Security Council spokesperson Bernadette Meehan remarked that "It remains our assessment that Iran does not exert command and control over the Houthis in Yemen".[235] Joost Hiltermann wrote that Iran does not control the Houthis' decision-making as evidenced by Houthis' flat rejection of Iran's demand not to take over Sanaa in 2015.[234] Thomas Juneau, writing in the journal, International Affairs, states that even though Iran's support for Houthis has increased since 2014, it remains far too limited to have a significant impact in the balance of power in Yemen.[236] The Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft argues that Teheran's influence over the movement has been "greatly exaggerated" by "the Saudis, their coalition partners (mainly the United Arab Emirates), and their [lobbyists] in Washington."[237]

A December 2009 cable between Sanaa and various intelligence agencies in the US diplomatic cables leak states that US State Dept. analysts believed the Houthis obtained weapons from the Yemeni black market and corrupt members of the Yemenis Republican Guard.[citation needed] On the edition of 8 April 2015 of PBS Newshour, Secretary of State John Kerry stated that the US knew Iran was providing military support to the Houthi rebels in Yemen, adding that Washington "is not going to stand by while the region is destabilised".[238]

Phillip Smyth of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy told Business Insider that Iran views Shia groups in the Middle East as "integral elements to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)". Smyth claimed that there is a strong bond between Iran and the Houthi uprising working to overthrow the government in Yemen. According to Smyth, in many cases Houthi leaders go to Iran for ideological and religious education, and Iranian and Hezbollah leaders have been spotted on the ground advising the Houthi troops, and these Iranian advisers are likely responsible for training the Houthis to use the type of sophisticated guided missiles fired at the US Navy.[239]

To some commentators (e.g., Alex Lockie of Business Insider), Iran's support for the revolt in Yemen is "a good way to bleed the Saudis", a recognized regional and ideological rival of Iran. Essentially, from that perspective, Iran is backing the Houthis to fight against a Saudi-led coalition of Gulf States whose aim is to maintain control of Yemen.[230] The discord has led some commentators to fear that further confrontations may lead to an all-out Sunni-Shia war.[240][page needed]

In early 2013, photographs released by the Yemeni government show the United States Navy and Yemen's security forces seizing a class of "either modern Chinese- or Iranian-made" shoulder-fired, heat-seeking anti-aircraft missiles "in their standard packaging", missiles "not publicly known to have been out of state control", raising concerns of Iran's arming of the rebels.[241] In April 2016, the U.S. Navy intercepted a large Iranian arms shipment, seizing thousands of AK-47 rifles, rocket-propelled grenade launchers, and 0.50-caliber machine guns, a shipment described as likely headed to Yemen by the Pentagon.[242][243] Based on 2019 reporting from The Jerusalem Post, the Houthis have also repeatedly used a drone nearly identical to Iran Aircraft Manufacturing Industrial Company's Ababil-T drone in strikes against Saudi Arabia.[244] In late October 2023, Israel stated that it had intercepted a "surface-to-surface long-range ballistic missile and two cruise missiles that were fired by the Houthi rebels in Yemen"; per reporting from Axios.com, this "was Israel's first-ever operational use of the Arrow system for intercepting ballistic missiles since the war began".[245]

The continuing interceptions and seizures of weapons at sea, attributed to Iranian origins, is a matter tracked by the United States Institute of Peace.[246]

Iranian IRGC involvement

In 2013, an Iranian vessel was seized and discovered to be carrying Katyusha rockets, heat-seeking surface-to-air missiles, RPG-7s, Iranian-made night vision goggles and artillery systems that track land and navy targets 40 km away. That was en route to the Houthis.[247]

In March 2017, Qasem Soleimani, the head of Iran's Quds Force, met with Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) to look for ways to what was described as "empowering" the Houthis. Soleimani was quoted as saying, "At this meeting, they agreed to increase the amount of help, through training, arms and financial support." Despite the Iranian government, and Houthis both officially denying Iranian support for the group. Brigadier General Ahmad Asiri, the spokesman of the Saudi-led coalition told Reuters that evidence of Iranian support was manifested in the Houthi use of Kornet anti-tank guided missiles which had never been in use with the Yemeni military or with the Houthis and that the arrival of Kornet missiles had only come at a later time.[248] In the same month the IRGC had altered the routes used in transporting equipment to the Houthis by spreading out shipments to smaller vessels in Kuwaiti territorial waters in order to avoid naval patrols in the Gulf of Oman due to sanctions imposed, shipments reportedly included parts of missiles, launchers, and drugs.[249]

In May 2018, the United States imposed sanctions on Iran's IRGC, which was also listed as a designated terrorist organization by the US over its role in providing support for the Houthis, including help with manufacturing ballistic missiles used in attacks targeting cities and oil fields in Saudi Arabia.[250]

In August 2018, despite previous Iranian denial of military support for the Houthis, IRGC commander Nasser Shabani was quoted by the Iranian Fars News Agency as saying, "We (IRGC) told Yemenis [Houthi rebels] to strike two Saudi oil tankers, and they did it", on 7 August 2018. In response to Shabani's account, the IRGC released a statement saying that the quote was a "Western lie" and that Shabani was a retired commander, despite no actual reports of his retirement after 37 years in the IRGC, and media linked to the Iranian government confirming he was still enlisted with the IRGC.[251] Furthermore, while the Houthis and the Iranian government have previously denied any military affiliation,[252] Iranian supreme leader Ali Khamenei openly announced his "spiritual" support of the movement in a personal meeting with the Houthi spokesperson Mohammed Abdul Salam in Tehran, in the midst of ongoing conflicts in Aden in 2019.[253][254]

In 2024, commanders from IRGC and Hezbollah were reported to be actively involved on the ground in Yemen, overseeing and directing Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping, according to a report by Reuters.[255]

In 2024 July United States targeted new sanctions focusing on IRGC ties with the group. Ansar Allah dismissed the sanctions as pathetic and powerless.[256]

North Korean involvement

In August 2018, Reuters reported that a confidential United Nations investigation had found the North Korean government had failed to discontinue its nuclear and missile delivery programs, and in conjunction, was "cooperating militarily with Syria" and was "trying to sell weapons to Yemen's Houthis".[257][32][33]

In January 2024, South Korea's Yonhap News Agency reported that North Korea had evidently shipped weapons to Houthis via Iran, based on the writings in Hangul script that were found on missiles launched towards Israel.[258]

North Korea considers the Houthis as a "resistance force".[259][260]

Russian involvement

In July 2024, The Wall Street Journal reported that US officials saw increasing indications that Russia was considering arming the Houthis with advanced anti-ship missiles via Iranian smuggling routes in response to US support for Ukraine during Russia's invasion.[261] However, it did not follow through due to pushback by the US and Saudi Arabia.[262]

In August 2024, Middle East Eye, citing a US official, reported that personnel of Russia's GRU were stationed in Houthi-controlled parts of Yemen to assist the militia's attacks on merchant ships.[263]

It is also noted that the Houthis owned Russian-made P-800 Oniks via Syria and Iran.[264]

Alleged human rights violations

According to the Panel of Experts on Yemen established pursuant to Security Council resolution 2140, the Houthis have carried out a wide range of human rights violations, including violations of international humanitarian law and abuse of women and children. Children as young as 13 have been arrested for "indecent acts" for alleged homosexual orientation or "political cases" when their families do not comply with Houthi ideology or regulations. Minors share cells with adult prisoners, and according to unspecified reports that the Panel has deemed "credible", boys held in Al-Shahid Al-Ahmar police station in Sana'a are systematically raped.[265][266] Aside from the Panel of Experts, London-based Arabic newspaper Asharq Al-Awsat alleges that the Houthis have revived slavery in Yemen.[267]

Child soldiers and human shields

Houthis have been accused of violations of international humanitarian law such as using child soldiers,[268][269][270] shelling civilian areas,[271] forced evacuations and executions.[272] According to Human Rights Watch, Houthis intensified their recruitment of children in 2015. The UNICEF mentioned that children with the Houthis and other armed groups in Yemen comprise up to a third of all fighters in Yemen.[273] Human Rights Watch has further accused Houthi forces of using landmines in Yemen's third-largest city of Taizz which has caused many civilian casualties and prevent the return of families displaced by the fighting.[274] HRW has also accused the Houthis of interfering with the work of Yemen's human rights advocates and organizations.[275]

In 2009, HRW researcher Christoph Wilcke said that although the Republic of Yemen Government accused the Houthis of using civilians as human shields, HRW did not have enough evidence to conclude that the Houthis were intentionally doing so but Wilcke admitted there may have been cases HRW was not able to document.[209] Akram Al Walidi, one of four journalists detained by the Houthis on spying charges[276] and then released in April 2023 as part of a prisoner exchange deal between the former and the internationally recognized government of Yemen, said he felt like the four were human shields after the Houthis moved them to one of their military camps at Sanaa in October 2020 since it was an expected target of Saudi airstrikes.[277]

Hostage-taking

According to the Human Rights Watch, the Houthis also use hostage taking as a tactic to generate profit. Human Rights Watch documented 16 cases in which Houthi authorities held people unlawfully, in large part to extort money from relatives or to exchange them for people held by opposing forces.[278]

Diversion of international aid

The United Nations World Food Programme has accused the Houthis of diverting food aid and illegally removing food lorries from distribution areas, with rations sold on the open market or given to those not entitled to it.[279] The WFP has also warned that aid could be suspended to areas of Yemen under the control of Houthi rebels due to "obstructive and uncooperative" Houthi leaders that have hampered the independent selection of beneficiaries.[280] WFP spokesman Herve Verhoosel stated "The continued blocking by some within the Houthi leadership of the biometric registration ... is undermining an essential process that would allow us to independently verify that food is reaching ... people on the brink of famine". The WFP has warned that "unless progress is made on previous agreements we will have to implement a phased suspension of aid". The Norwegian Refugee Council has stated that they share the WPF frustrations and reiterate to the Houthis to allow humanitarian agencies to distribute food.[281][282]

Abuse of women and girls

The United Nations Human Rights Council published a report covering the period July 2019 to June 2020, which contained evidence of the Houthis' recruitment of boys as young as seven years old and the recruitment of 34 girls aged between 13 and 17 years of age, to act as spies, recruiters of other children, guards, medics, and members of a female fighting force. Twelve girls suffered sexual violence, arranged marriages, and child marriages as a result of their recruitment.[283]

Under Houthi controlled areas women have been blocked from travelling without a mahram (male guardian) even for essential healthcare. This also affected humanitarian operations by the United Nations in Yemen forcing female staff to office jobs. The Houthis use allegations of prostitution as a tool for public defamation against Yemeni women including those in the diaspora engaged in politics, civil society or human rights activism alongside threats to individuals and families. Women in detention are sexually assaulted and have been subjected to virginity tests and are often blocked from access to essential goods. Torture of female detainees is also carried out by the Zaynabiyat, the Female police wing of the Houthis.[265][non-primary source needed]

UN Panel of Experts on Yemen discovered instances of Houthi rape of female detainees to "purify" them, as a punishment, or to coerce confessions. The Panel documented cases where Houthis forced detained women to become sex workers that also collect information for the Houthis. Documented instances include in 2021 where a female detainee was forced to have sexual intercourse with multiple men at Houthi detention centers as part of her preparation to be forced as a sex worker for important clients while also obtaining information. The Panel also received information of another detainee who was forced to become a prostitute to gather information for the Houthis in return for their release and another similar instance had been documented in 2019. This have also resulted in women who had been detained by Houthis being ostracized by society and one instance where the woman was killed by her family for bringing shame upon the family.[266][non-primary source needed]

Anadolu Agency reported of Yemen-based rights groups documenting 1,181 violations against women committed by Houthis from 2017 to 2020.[284] Yemeni activist Samira Abdullah al-Houry was held in a Houthi jail for three months and gave numerous interviews after her release on alleged torture and rape by Houthi guards.[285] Her testimony contributed to UN Security Council sanctions being imposed on two Houthi security officials in February 2021. It was later alleged that she admitted some of her testimony was untrue and she had embellished claims at the request of Saudi officials.[286]

Abuse of LGBTI people

According to Amnesty International on 9 February 2024, two Houthi-run courts in Yemen sentenced 48 individuals either to death, flogging or prison over charges related to same-sex conduct in the past month.[287]

Abuse of migrants

According to Human Rights Watch, Houthi militias have "beaten, raped, and tortured detained migrants and asylum seekers from the Horn of Africa."[288] UN experts have warned that female migrants face sexual violence, forced labor, and forced drug trafficking by smugglers who collaborate with the Houthi-controlled Yemen Immigration, Passport and Nationality Authority (IPNA).[289]

Governance

According to a 2009 leaked US Embassy cable, Houthis have reportedly established courts and prisons in areas they control. They impose their own laws on local residents, demand protection money, and dispense rough justice by ordering executions. AP's reporter, Ahmad al-Haj argued that the Houthis were winning hearts and minds by providing security in areas long neglected by the Yemeni government while limiting the arbitrary and abusive power of influential sheikhs. According to the Civic Democratic Foundation, Houthis help resolve conflicts between tribes and reduce the number of revenge killings in areas they control. The US ambassador believed that the reports that explain Houthi role as arbitrating local disputes were likely.[209]

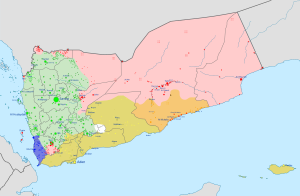

Houthi-controlled areas of Yemen

The Houthis exert de facto authority over the bulk of North Yemen.[290] As of 28 April 2020, they control all of North Yemen except for Marib Governorate.[291][292]

See also

- Outline of the Yemeni crisis, revolution, and civil war (2011–present)

- Timeline of the Yemeni crisis (2011–present)

- United States conflict with Houthi militias (2023–present)

- Houthi involvement in the 2023 Israel–Hamas war

Notes

References

- ^ "Mohammed Abdul Salam denies news in Saudi channel". Yemen Press. Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ "Infographic: Yemen's war explained in maps and charts". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ "What is the Houthi Movement?". Tony Blair Faith Foundation. 25 September 2014. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ a b c Mohammed Almahfali, James Root (13 February 2020). "How Iran's Islamic Revolution Does, and Does Not, Influence Houthi Rule in Northern Yemen". Sana'a Center For Strategic Studies. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ a b The World Almanac of Islamism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. 27 October 2011. ISBN 9781442207158. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ "The Islamist philosophy 'Qutbism' could be entering America's national security vernacular". The Hill. 19 December 2017. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

McMaster's Qutbism comments are occurring simultaneously with U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Halley's proof of Iranian support for Houthi missiles. The timing of the Trump administration's push connects the dots between Iran, Houthis and Qutabists supported by Turkey and Qatar.

- ^ "كيف تأثر أنصار الله بجماعة الإخوان المسلمين؟". Al-Nkkar (in Arabic). 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Yemen: Civil War and Regional Intervention" (PDF). Congressional Research. 8 December 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

The Houthi movement (formally known as Ansar Allahor Partisans of God) is a predominantly Zaydi Shia revivalist political and insurgent movement formed in the northern Yemeni governorate of Saada under the leadership of members of the Houthi family.

- ^ a b c "Houthis". Sabwa Center. 7 October 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Cameron Glenn (29 May 2018). "Who are Yemen's Houthis?". Wilson Center. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Asher Orkaby (25 March 2015). "Houthi Who? A History of Unlikely Alliances in an Uncertain Yemen". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ Ahmad, Majidyar. "New Houthi-imposed university curriculum reportedly glorifies Iran, promotes sectarianism". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ "Houthi Directives: Sectarian Programs Mandated in Schools Across 3 Yemeni Provinces". Asharq Al Awsat. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ahmed Nagi (19 March 2019). "Yemen's Houthis Used Multiple Identities to Advance". Carnegie Middle East Center. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Yemen: Treatment of Sunni Muslims by Houthis in areas under Houthi control (2014 – September 2017)". Refworld. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

a Research Associate at the London Middle East Institute at the University of London [...] noted that most of the area controlled by the Houthis is inhabited by Zaydis. But they also have many Sunni supporters in the areas they control [...] Since the Houthis have effectively taken over the country, they have been suspicious of Sunnis. The group believes that those who do not swear allegiance to it are working with the Saudi-led coalition. As a result, Sunnis have been discriminated against... Sunnis face discrimination that those of the Zaydi persuasion to which the Huthis belong do not experience. This includes women... in issues such as education, the curriculum has been changed by the Houthis to be 'more sectarian and [intolerant]'

- ^ "Houthis revive Shiite festivals to strengthen grip on north". Al-Monitor. 8 August 2021. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021.

Since the Houthi seizure of Sanaa in 2014, the group has brought new sectarian pressure to Yemen's north, forcing both Shiites and Sunnis to observe Shiite customs

- ^ MAYSAA SHUJA AL-DEEN. "Yemen's War-torn Rivalries for Religious Education". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Plotter, Alex (4 June 2015). "Yemen in crisis". Esquire. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ "Why Washington May Side With Yemen's New anti-American Rulers". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ "Yemeni embassy in DC condemns 'anti-American', 'anti-Semitic' Houthi ceremony". english.alarabiya.net. 7 November 2020. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Persecution Defines Life for Yemen's Remaining Jews". The New York Times. 19 February 2015. Archived from the original on 15 October 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ "Yemen: Further information: Arbitrarily detained Baha'is must be released". Amnesty International. 20 December 2023.

On 17 October 2023, the UN Human Rights Council passed a resolution calling on the Huthi de facto authorities to "remove the obstacles that prevent access by relief and humanitarian aid, to release kidnapped humanitarian workers and to end violence and discrimination against women and targeting based on religion or belief."

- ^ "For Yemen's gay community social media is a saviour". The Irish Times. 22 August 2015.

- ^ Almasmari, Hakim. "Medics: Militants raid Yemen town, killing dozens". Archived 29 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, CNN, 27 November 2011.

- ^ Houthis Kill 24 in North Yemen Archived 19 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, 27 November 2011.

- ^ "The myth of stability: Infighting and repression in Houthi-controlled territories". OCHA. 10 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Iranian support seen crucial for Yemen's Houthis". Reuters. 15 December 2014. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ "Yemen's Houthi-led govt appoints new envoy to Syria". Middle East Monitor. 12 November 2020. Archived from the original on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

Yemen's Houthi-led National Salvation Government (NSG) has appointed a new ambassador to Syria, one of the countries alongside Iran which recognises the Sanaa-based government.

- ^ "Syria expels Houthi 'diplomatic mission' in Damascus". Arab News. 12 October 2023.

- ^ "North Korea's Balancing Act in the Persian Gulf". The Huffington Post. 17 August 2015. Archived from the original on 17 August 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

North Korea's military support for Houthi rebels in Yemen is the latest manifestation of its support for anti-American forces.

- ^ "The September 14 drone attack on Saudi oil fields: North Korea's potential role | NK News". 30 September 2019. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ a b "North Korea is hiding nukes and selling weapons, alleges confidential UN report". CNN. 5 February 2019. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

The summary also accuses North Korea of violating a UN arms embargo and supplying small arms, light weapons and other military equipment to Libya, Sudan, and Houthi rebels in Yemen, through foreign intermediaries.

- ^ a b "Secret UN report reveals North Korea attempts to supply Houthis with weapons". Al-Arabiya. 4 August 2018. Archived from the original on 4 August 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

The report said that experts were investigating efforts by the North Korean Ministry of Military Equipment and Korea Mining Development Trading Corporation (KOMID) to supply conventional arms and ballistic missiles to Yemen's Houthi group.

- ^ "Panel investigates North Korean weapon used in Mogadishu attack on UN compound". 3 March 2021. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ "Just how neutral is Oman in Yemen war?". Al-Monitor. 12 October 2016. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

Just how neutral is Oman in Yemen war?

- ^ "Yemen War and Qatar Crisis Challenge Oman's Neutrality". Middle East Institute. 6 July 2017. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

Yemen War and Qatar Crisis Challenge Oman's Neutrality

- ^ "Oman is a mediator in Yemen. Can it play the same role in Qatar?". The Washington Post. 22 July 2017. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

Oman is a mediator in Yemen. Can it play the same role in Qatar?

- ^ "Oman denies arms smuggled through border to Houthis". Middle East Eye. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ "Mana'a and al-Ahmar received money from Gaddafi to shake security of KSA, Yemen". 4 September 2011. Archived from the original on 10 February 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Mathews, Sean (2 August 2024). "Exclusive: US intelligence suggests Russian military is advising Houthis inside Yemen". Middle East Eye.

- ^ "الجيش اليمني مدعوماً بأنصار الله يهاجم تحالف العدوان ومرتزقته في معاقله بتعز" [The Yemeni army, backed by Ansar Allah, attacks the coalition of aggression and its mercenaries in its strongholds in Taiz]. عاجل Breaking News (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- ^ "Yemen's Military: From the Tribal Army to the Warlords". 19 March 2018. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ "Yemen's General People's Congress calls for 'uniting against Iranian project'". English.AlArabiya.net. 3 December 2017. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ "Death of a leader: Where next for Yemen's GPC after murder of Saleh?". Middle East Eye. 23 January 2018. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ "Source: Hezbollah, Iran helping Hawthi rebels boost control of Yemen's capital". Haaretz. 27 September 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Rafi, Salman (2 October 2015). "How Saudi Arabia's aggressive foreign policy is playing against itself". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "Iraq's Nujaba, Yemen's Ansarullah Discuss US Threats – World news". Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ "State Department Report 1: Iran's Support for Terrorism". The Iran Primer. 28 September 2018. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Houthis, Hamas merge diplomacy around prisoner releases – Al-Monitor: Independent, trusted coverage of the Middle East". 5 January 2021.

- ^ "Hamas awards 'Shield of Honor' to Houthi representative in Yemen, sparking outrage in Saudi Arabia". 16 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Egypt, Jordan, Sudan and Pakistan ready for ground offensive in Yemen: report". The Globe and Mail. 26 March 2015. Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia launches airstrikes in Yemen". CNN. 26 March 2015. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "Kosovo came out in support of the USA and Britain against the Houthi rebels". Koha Ditore. 12 January 2024.

- ^ "Somalia condemns Houthi attack on Saudi Arabia". Garowe Online. 21 March 2021.

- ^ "Somalia lends support to Saudi-led fight against Houthis in Yemen". The Guardian. 7 April 2015.

- ^ "Belgium supports US-UK operation against Houthi rebels". The Brussels Times. 12 January 2024.

- ^ "France Should Stop Fueling Saudi War Crimes in Yemen". Human Rights Watch. 17 May 2019. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "Yemen: Why is the war there getting more violent?". BBC News. 22 March 2022. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "Americans and British attack Houthi targets in Yemen, the Netherlands supports". NOS Nieuws. Nederlandse Omroep Stichting. 12 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d Riedel, Bruce (18 December 2017). "Who are the Houthis, and why are we at war with them?". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ "Yemen's Houthis: New members of Iran's anti-Israeli/anti-American axis". JPost.com. 28 May 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ "Exclusive: UK Helping Saudi's Yemen Campaign". Sky News. 7 January 2016. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "Biden says Canada among nations supporting operation to stop Houthi attacks on commercial ships". CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 12 January 2024.

- ^ Lyons, John (12 January 2024). "Today, Biden said Australia was one of a number of allies that had provided support for the initial strikes". ABC News (Australia). Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "Yemen's Houthis: New members of Iran's anti-Israeli/anti-American axis". Jerusalem Post. 28 May 2017. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ "The US and Allies Take Aim at Houthis and Iran With New Maritime Security Force". MSN.

- ^ "New Zealand backs UK, US attacks on Houthi rebels in Yemen". Radio New Zealand. Reuters. 12 January 2024.

- ^ Baldor, Lolita C.; Copp, Tara (11 January 2024). "US, British militaries launch massive retaliatory strike against Iranian-backed Houthis in Yemen". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 12 January 2024.

- ^ Gupta, Shishir (19 December 2023). "India stations two destroyers off the coast of Aden for maritime security". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 7 January 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ Mallawarachi, Bharatha (9 January 2024). "Sri Lanka to join US-led naval operations against Houthi rebels in Red Sea". ABC News. Archived from the original on 10 January 2024. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ "Yemen's Houthi rebels declare support for Russia's Ukraine annexation". The New Arab. 22 February 2022. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Waraich, Omar (11 January 2016). "Pakistan Is Caught in the Middle of the Conflict Between Iran and Saudi Arabia". Time.

But last April, Pakistan's Parliament unanimously voted to decline a Saudi request to participate in its coalition fighting in Yemen against the allegedly Iranian-backed Houthi rebels. At the time, the Pakistanis said they were overstretched at home and unwilling to pick sides between a 'brotherly' Saudi Arabia and a 'neighborly' Iran.

- ^ Reporter, Aadil Brar China News (22 February 2024). "China sends warships to the Middle East". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 25 February 2024. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ "3 STC fighters killed in Houthi attack in southern Yemen". Middle East Monitor. 30 September 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ "Rebels in Yemen abduct Sunni rivals amid Saudi airstrikes". 5 April 2015. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2018 – via The CBS News.

Muslim Brotherhood's branch in Yemen and a traditional power player in Yemen, had declared its support for the Saudi-led coalition bombing campaign against the rebels and their allies.

- ^ "Hamas supports military operation for political legitimacy in Yemen". 29 March 2015. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia's Problematic Allies against the Houthis". 14 February 2016. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2018 – via www.thecairoreview.com.

Saudi Arabia made sure to repair its relations with the MB Islah Party.. Consequently, Islah, which can get the job done in parts of northern Yemen, is one of a wide range of anti-Houthi/Saleh elements

- ^ "Who are Yemen's Houthis?". 29 April 2015. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2018 – via Wilson Center.

The Houthis have a tense relationship with Islah, a Sunni Islamist party with links to the Muslim Brotherhood. Islah claims the Houthis are an Iranian proxy, and blames them for sparking unrest in Yemen. The Houthis, on the other hand, have accused Islah of cooperating with al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

- ^ "Al-Qaeda Announces Holy War against Houthis- Yemen Post English Newspaper Online". yemenpost.net. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ a b Hussam Radman, Assim al-Sabri (28 February 2023). "Leadership from Iran: How Al-Qaeda in Yemen Fell Under the Sway of Saif al-Adel". Sana'a Center For Strategic Studies. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Islamic State leader urges attacks in Saudi Arabia: speech". Reuters. 13 November 2014. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "Yemen's National Defense Council labels Houthis as terror group".

- ^ "Houthis added to Yemen's terrorist list". 25 October 2022.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia designates Muslim Brotherhood terrorist group". Reuters. 7 March 2014. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "مجلس الوزراء يعتمد قائمة التنظيمات الإرهابية. | Wam". Archived from the original on 17 November 2014.

- ^ Hansler, Jennifer (17 January 2024). "Biden administration re-designates Houthis as Specially Designated Global Terrorists". CNN. Archived from the original on 17 January 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ "List of Individuals, Entities and Other Groups and Undertakings Declared by the Minister of Home Affairs As Specified Entity Under Section 66B(1)" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs of Malaysia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ "Listed terrorist organisations: Ansar Allah". Australia Government. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ "Australia officially designates Houthis as a terrorist organization". The Jerusalem Post. 24 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Do not call the Ansar Allah movement 'Houthi'!". IWN. 23 April 2021. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Hoffman, Valerie J. (28 February 2019). Making the New Middle East: Politics, Culture, and Human Rights. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815654575. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Yemeni forces kill rebel cleric". BBC News. 10 September 2004. Archived from the original on 21 November 2006.

- ^ Streuly, Dick (12 February 2015). "5 Things to Know About the Houthis of Yemen". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- ^ a b c "Houthi propaganda: following in Hizbullah's footsteps". alaraby. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Yemen: The conflict in Saada Governorate – analysis". IRIN. 24 July 2008. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ "Debunking Media Myths About the Houthis in War-Torn Yemen · Global Voices". GlobalVoices.org. 1 April 2015. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ a b c Juneau, Thomas (May 2016). "Iran's policy towards the Houthis in Yemen: a limited return on a modest investment". International Affairs. 92 (3): 647–663. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12599. ISSN 0020-5850.

- ^ "Yemen". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Yemen's Houthis form own government in Sanaa". Al Jazeera. 6 February 2015. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ Islam Hassan (31 March 2015). "GCC's 2014 Crisis: Causes, Issues and Solutions". Gulf Cooperation Council's Challenges and Prospects. Al Jazeera Research Center. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ a b "US warship intercepts missiles fired from Yemen 'potentially towards Israel'". BBC News. 20 October 2023. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Who are the Houthis, the group attacking ships in the Red Sea?". The Economist. 12 December 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

Since the bombardment of Gaza began, the Houthis, a Yemeni rebel group, have launched a series of attacks on cargo ships. The insurgents, who are backed by Iran, say they are acting in solidarity with Palestinians. They have threatened to attack any ship bound for or leaving Israel without delivering humanitarian aid to Gaza.

- ^ a b c "Yemen crisis: Who is fighting whom?". BBC News. 2018. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ a b c d Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Yemen: Treatment of Sunni Muslims by Houthis in areas under Houthi control (2014 – September 2017)". Refworld. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "Rebel Governance: Ansar Allah in Yemen and the Democratic Union Party in Syria" (PDF). Peace Research Institute Oslo. PRIO. 2022.

- ^ Agence France-Presse (23 October 2019). "Yemeni government, separatists seen inking deal to end Aden standoff". Euronews. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ a b Al Batati, Saeed (21 August 2014). "Who are the Houthis in Yemen?". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 23 August 2014.

- ^ Freeman, Jack (2009). "The al Houthi Insurgency in the North of Yemen: An Analysis of the Shabab al Moumineen". Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 32 (11): 1008–1019. doi:10.1080/10576100903262716. ISSN 1057-610X. S2CID 110465618.

- ^ a b c d "Regime and Periphery in Northern Yemen: The Huthi Phenomenon" (PDF). RAND. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Yemen's Abd-al-Malik al-Houthi". BBC News. 3 October 2014. Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ "Profile: The crisis in Yemen". thenational.scot. 23 March 2015. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ a b Adam Baron (25 March 2015). "What Went Wrong with Yemen". Politico. Archived from the original on 12 August 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Yemen: The conflict in Saada Governorate – analysis". IRIN. 24 July 2008. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ "Yemeni forces kill rebel cleric". BBC News. 10 September 2004. Archived from the original on 21 November 2006.

- ^ "The Huthis: From Saada to Sanaa". Middle East Report N°154. International Crisis Group. 10 June 2014. Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ "Yemen Al Houthi rebels slam federation plan as unfair". Gulf News. 11 February 2014. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ al-Hassani, Mohammed (6 February 2014). "Houthi Spokesperson Talks to the Yemen Times". Yemen Times. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ "Houthis Close to Control Hajjah Governorate, Amid Expectations of Expansion of Control over Large Parts of Northern Yemen". Islam Times. 29 November 2011. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ "Al-Houthi Expansion Plan in Yemen Revealed". Yemen Post. 9 November 2011. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011.

- ^ "New war with al-Houthis is looming". Yemen observer. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ^ "Houthis seize government buildings in Sanaa". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 22 September 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ^ Kareem Fahim (7 January 2015). "Violence Grows in Yemen as Al Qaeda Tries to Fight Its Way Back". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ "Yemen Houthi rebels 'seize presidential palace'". BBC News. 20 January 2015. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Death toll hits 142 from attacks in Yemen mosques". Al Bawaba. 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015.

- ^ "Saudi 'Decisive Storm' waged to save Yemen". Al Arabiya News. 26 March 2015. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015.