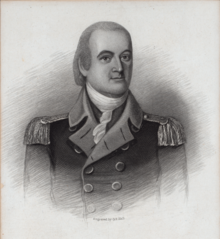

William Alexander, Lord Stirling

William Alexander | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 27, 1725 New York City, Province of New York |

| Died | January 15, 1783 (aged 57–58) Albany, New York, U.S. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1775–1783 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Commands held | 1st New Jersey Regiment Continental Army (2 months) |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War: • Battle of Long Island • Battle of Trenton • Battle of Brandywine • Battle of Germantown • Battle of Monmouth |

| Spouse(s) |

Sarah Livingston

(m. 1747) |

| Relations | Philip Livingston (father-in-law) William Livingston (brother-in-law) |

William Alexander, also known as Lord Stirling (December 27, 1725[1] – January 15, 1783), was a Scottish-American major general during the American Revolutionary War. He was considered male heir to the Scottish title of Earl of Stirling through Scottish lineage (being the senior male descendant of the paternal grandfather of the 1st Earl of Stirling, who had died in 1640), and he sought the title sometime after 1756. His claim was initially granted by a Scottish court in 1759; however, the House of Lords ultimately overruled Scottish law and denied the title in 1762. He continued to hold himself out as "Lord Stirling" regardless.[2]

Lord Stirling commanded a brigade at the Battle of Long Island, his rearguard action resulting in his capture but enabling General George Washington's troops to escape. Stirling later was returned by prisoner exchange and received a promotion; continuing to serve with distinction throughout the war. He also was trusted by Washington and, in 1778, exposed the Conway Cabal.

Early life[edit]

William was born December 27, 1725, in New York City in what was then the Province of New York, a part of British America.[3] He was the son of lawyer James Alexander and merchant Mary Spratt Provoost Alexander. His nephew was Senator John Rutherfurd (1760–1840).

He was educated, ambitious, and proficient in mathematics and astronomy, he then joined his mother, Mary Alexander, the widow of David Provost, in the provision business left her by the death of her first husband.[4]

Earldom of Stirling[edit]

The Earldom of Stirling in the Scottish peerage became dormant or extinct upon the death of Henry Alexander, 5th Earl of Stirling. William Alexander's father, James Alexander, who had fled from Scotland in 1716 after participating in the Jacobite rising, did not claim the title. Upon his father's death, William lay claim to the title and filed suit. His relationship to the 5th Earl was not through heirs of the body, but through heirs male collateral. Thus, he was not entitled to a title inherited only by the male line descendants of the 1st Earl. However, the inheritance by proximity of blood had been questioned. It was settled in his favor, by a unanimous vote of a jury of twelve in a Scottish court in 1759, and William claimed the disputed title of Earl of Stirling. It is not clear whether the case went to court because of an unfavorable answer from the Lord Lyon King of Arms concerning the peerage.[5]

Legal opinion was that this was a "Scottish heir" problem, so the title right was solved. This might have been unopposed, as indisputable peerage, except there was a catch. The two sponsors, Archibald Campbell, 3rd Duke of Argyll, and John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, encouraged William Alexander through representatives to seek the title. The goal was vast land holdings in America that the holder of the title was to enjoy. The sponsors were to receive money and land if William was successful. With this in mind, William decided to petition the House of Lords. A friend and professional agent in Scotland, Andrew Stuart, wrote and advised William not to petition the House of Lords. He felt that the right of indisputable peerage demanded that William just claim the titles as others had done. His opinion was that others lay similar claims to titles so he would not be opposed. It is possible William did not want to commit a crime, or be found out, and if the House of Lords advanced his claim it would be forever legal. One problem was that to prove his claim in court, two old men were called upon to testify that William did in fact descend from the first Earl through his uncle named John Alexander. This might have been persuasive in a Scottish court but might be considered dubious in England.[6]

He inherited a large fortune from his father, dabbled in mining and agriculture, and lived a life filled with the trappings befitting a Scottish lord. This was an expensive lifestyle, and he eventually went into debt to finance it. He began building his grand estate in the Basking Ridge section of Bernards Township, New Jersey, and upon its completion, sold his home in New York and moved there. George Washington was a guest there on several occasions during the revolution and gave away Alexander's daughter at her wedding. In 1767, the Royal Society of Arts awarded Alexander a gold medal for accepting the society's challenge to establish viticulture and wine making in the North American colonies by cultivating 2,100 grape (V. vinifera) vines on his New Jersey estate.[7] Alexander was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1770.[8]

American Revolution[edit]

When the American Revolutionary War began, Stirling was made a colonel in the New Jersey colonial militia.[9] Because he was wealthy and willing to spend his own money in support of the Patriot cause, he outfitted his unit, the 1st New Jersey Regiment, at his own expense. He distinguished himself early by leading a group of volunteers in the capture of an armed British naval transport.

The Second Continental Congress appointed him brigadier general in the Continental Army in March 1776.[9]

Prisoner of war[edit]

At the Battle of Long Island, in August of that year, Stirling led a brigade in Sullivan's division. He held against repeated attacks by a superior British Army force under the command of Gen. James Grant at the Old Stone House near Gowanus Creek and took heavy casualties. Additional redcoats had made a wide flanking attack sweeping to the east through the lightly-guarded Jamaica Pass, one of a series of low entrances through the ridge line of hills running east to west through the center of Long Island, catching the Patriot forces on their left side. Stirling ordered his brigade to retreat while he himself kept the 1st Maryland Regiment as rear-guard. Though heavily outnumbered he led a counter-attack, eventually dispersing his men before being overwhelmed. Stirling himself was taken prisoner but he had held the British forces occupied long enough to allow the main body of Washington's army to escape to defensive positions at Brooklyn Heights, along the East River shoreline. Later, under the cover of a miraculous fog which enveloped the river, Washington was able to barge his remaining troops and equipment across back to Manhattan and New York City.

Because of his actions at Long Island, one newspaper called Stirling "the bravest man in America", and he was praised by both Washington and the British for his bravery and audacity. Later a commemorative monument was erected at the site of the military engagements and embattled retreat and the plot of land deeded to the State of Maryland near Prospect Park as a sacred parcel of "blood-soaked Maryland soil".

Balance of War[edit]

Stirling was released in a prisoner exchange, in return for governor Montfort Browne, and promoted to the rank of major general,[10][vague] and became one of Washington's most able and trusted generals. Washington held him in such high regard that during the second Middlebrook encampment, he placed him, headquartered at the nearby Van Horne House, in command of the Continental Army for nearly two months, from December 21, 1778, when he left to meet with Congress in Philadelphia, until he returned about February 5, 1779.[11]

Throughout most of the war Stirling was considered to be third or fourth in rank behind General Washington. At the Battle of Trenton on December 26, 1776, he received the surrender of a Hessian auxiliary regiment. On June 26, 1777, at Metuchen, he awaited an attack, contrary to Washington's orders. His position was turned and his division defeated, losing two guns and a hundred fifty men in the Battle of Short Hills. Subsequent battles at Brandywine and Germantown in Pennsylvania during the campaign to defend the Patriot capital of Philadelphia and Monmouth in New Jersey, cemented his reputation for bravery and sound tactical judgment.[citation needed]

Stirling also played a part in exposing the Conway Cabal, a conspiracy of disaffected Continental officers looking to remove Washington as Commander-in Chief and replace him with General Horatio Gates. According to one author, "Lord Stirling never gave dull parties. His dinners were a Niagara of liquor. His love of the bottle was notorious..." One of Gates' aides, James Wilkinson stopped at Stirling's headquarters at Reading, Pennsylvania and stayed for dinner because it was raining. Wilkinson got drunk and began repeating criticisms of Washington that he had heard from other officers. Finally, he claimed to have read a letter from Thomas Conway to Gates that stated, "Heaven has determined to save your country or a weak general and bad counselors would have ruined it". The loyal Stirling wrote to Washington the next day and repeated what Wilkinson said. Washington, in turn, wrote to Conway, repeating what Stirling had written. Once exposed, the cabal went to pieces. Conway denied ever writing the note, Wilkinson called Stirling a liar, and Gates made statements that made himself look guilty.[12]

At the Battle of Monmouth on 28 June 1778, Stirling commanded the American Left Wing. This included the 1st (429), 2nd (487), and 3rd Pennsylvania (438) Brigades, John Glover’s (636), Ebenezer Learned's (373), and John Paterson’s (485) Massachusetts Brigades.[13] He displayed tactical judgment in posting his batteries, and repelled with heavy loss an attempt to turn his flank. During the devastating winter encampment at Valley Forge, northwest of British–held Philadelphia, his military headquarters have been preserved.[14] In January 1780, he led an ineffective raid against Staten Island on the western shores of New York Bay.

When Washington and the French comte de Rochambeau took their conjoined armies south for the climactic Battle of Yorktown in 1781, Stirling was appointed commander of the elements of the Northern Army, left behind to guard New York and was sent up the Hudson River to Albany. He died shortly thereafter in January 1783.[9]

Personal life[edit]

In 1747, William Alexander married Sarah Livingston (1725–1805), the daughter of Philip Livingston, 2nd Lord of Livingston Manor.[15] Sarah was also the sister of Governor William Livingston. Together, William and Sarah had two daughters and one son:[15]

- William Alexander

- Mary Alexander (1749–1820), who married wealthy merchant Robert Watts (1743–1814), son of John Watts of New York.[16]

- Catherine Alexander (1755–1826), who married Continental Congressman William Duer (1743–1799).

Always a heavy drinker, Alexander was in poor health by 1782, suffering from severe gout and rheumatism. He died in Albany on 15 January 1783.[9] His death occurred just months before the official end of the American War of Independence with the Treaty of Paris of 1783. A memorial tablet to the Alexander family can be found in the Churchyard of Trinity Church, facing the historic Wall Street district (adjoining nearby St. Paul's Chapel), in New York City.[17]

Descendants[edit]

Through his daughter Catherine, he is grandfather to college president William Alexander Duer (1780–1858) and noted lawyer and jurist John Duer (1782–1858). He is also great-grandfather of U.S. Congressman William Duer (1805–1879) and great-great-great-grandfather of writer and suffragette Alice Duer Miller (1874–1942).

Through his daughter Mary, he is great-grandfather of General Stephen Watts Kearny (1794–1848) and great-great-grandfather of General Philip Kearny, Jr. (1815–1862), who died in action during the U.S. Civil War.

Legacy[edit]

In honor of Alexander:

- MS51, a Middle School on the former Gowanus battlefield, is named William Alexander Middle School[18]

- Stirling, New Jersey, an unincorporated community in Long Hill Township is located a short distance from Alexander's house in Basking Ridge

- Lord Stirling Community School, a public elementary school in New Brunswick, New Jersey[19]

- Lord Stirling Park in Basking Ridge, New Jersey is located on part of his estate

- Sterling Hill Mine was named after him, as he once owned the property

- Lord Stirling 1770s Festival[20]

- The town of Sterling, Massachusetts

- Sterling Place in Brooklyn, NY[21]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Individual biography". www.albany.edu. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ Abbe-Barrymore (1928). "Dictionary of American Biography". Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. pp. 175–76. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ Bielinski, Stefan. "William Alexander". exhibitions.nysm.nysed.gov. New York State Museum. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Johnson, Rossiter, ed. (1906). "Alexander, William". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Vol. 1. Boston: American Biographical Society. p. 77.

- ^ Lawrence, Ruth (2003). "Maj. Gen. William Alexander, Lord Stirling and Sara Livingston". InterMedia Enterprises. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ Duer, William Alexander (1847). "The Life of William Alexander. Earl of Stirling". Wiley and Putnam, New York. pp. 27–49. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

DB1.1

- ^ McCormick, Richard P. "The Royal Society, The Grape and New Jersey" in Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, Volume LXXXI, Number 2, (April 1953); and later in Journal of the Royal Society of Arts (January 1962).

- ^ "APS Member History".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Who Was Who in American History – the Military. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1975. p. 6. ISBN 0837932017.

- ^ "This page has been moved". state.nj.us. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- ^ Washington, George (February 6, 1779). "General Orders, 6 February 1779". Founders Online, National Archives.

- ^ Preston, John Hyde (1962). Revolution 1776. New York, N.Y.: Washington Square Press, Inc.

- ^ Morrissey, Brendan (2008). Monmouth Courthouse 1778: The last great battle in the North. Long Island City, N.Y.: Osprey Publishing. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-1-84176-772-7.

- ^ "National Historic Landmarks & National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania" (Searchable database). ARCH: Pennsylvania's Historic Architecture & Archaeology. Retrieved November 2, 2012. Note: This includes Stacks, David C. (June 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Maj. Gen. Lord Stirling Quarters" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 2, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Livingston, Edwin Brockholst (1910). The Livingstons of Livingston Manor: Being the History of that Branch of the Scottish House of Callendar which Settled in the English Province of New York During the Reign of Charles the Second; and Also Including an Account of Robert Livingston of Albany, "The Nephew," a Settler in the Same Province and His Principal Descendants. Knickerbocker Press. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ^ "Maj.Gen. William Alexander, Lord Stirling and Sarah Livingston". 2004. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ^ Museum of the City of New York

- ^ "About Us/Admissions". MS 51 – William Alexander Middle School. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ^ Draper, Eshaya. "Lord Stirling Community School / Homepage". New Brunswick Public Schools. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ Mustac, Frank (September 11, 2009). "Living-history 'Lord Stirling 1770s Festival' is 4 October at Environmental Education Center". New Jersey On-Line. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ^ Benardo, Leonard (2006). Brooklyn By Name How the Neighborhoods, Streets, Parks, Bridges, and More Got Their Names. NYU Press. pp. 69–70. ISBN 9780814791493.

Further reading[edit]

- William Alexander, Lord Stirling: George Washington's Noble General, Paul David Nelson, University of Alabama Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-8173-5083-3

- Alexander, William, pages 175/76 in: Dictionary of American biography, Volume I. Edited by Alan Johnson, Publisher: C. Scribner's Sons New York, 1943

- The life of William Alexander, Earl of Stirling, Major-General in the Army of the United States during the Revolution: with selections from his correspondence. Collections of New Jersey Historical Society, Vol. II. By his Grandson William Alexander Duer. Published by Wiley & Putnam, New York 1847

External links[edit]

Works related to William Alexander, Lord Stirling at Wikisource

Works related to William Alexander, Lord Stirling at Wikisource

- Henderson, Thomas Finlayson (1885). "Alexander, William (1726-1783)". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 01.

- "Alexander, William". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- "Stirling, William Alexander, (titular) Earl of". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- 1726 births

- 1783 deaths

- American Revolutionary War prisoners of war held by Great Britain

- Continental Army generals

- Members of the New Jersey Provincial Council

- Continental Army officers from New Jersey

- People from Bernards Township, New Jersey

- Military personnel from New York City

- American people of Dutch descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- Royal Army Service Corps officers

- British military personnel of the French and Indian War

- New Jersey wine

- People from colonial New York

- People from colonial New Jersey

- Burials at Trinity Church Cemetery

- Presidents of the Saint Andrew's Society of the State of New York

- 18th-century American politicians

- Alexander family (British aristocracy)

- Members of the American Philosophical Society