Albania

Republic of Albania Republika e Shqipërisë (Albanian) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Ti Shqipëri, më jep nder, më jep emrin Shqipëtar "You Albania, give me honour, you give me the name Albanian" | |

| Anthem: "Himni i Flamurit" "Hymn to the Flag" | |

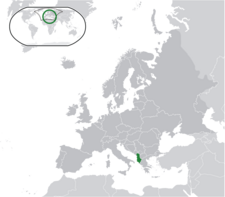

Location of Albania (green) | |

| Capital and largest city | Tirana 41°19′N 19°49′E / 41.317°N 19.817°E |

| Official languages | Albanian |

| Recognised minority languages | |

| Religion (2023) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Albanian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Bajram Begaj | |

| Edi Rama | |

| Elisa Spiropali | |

| Legislature | Kuvendi |

| Establishment history | |

| 1190 | |

| February 1272 | |

| 1368 | |

| 2 March 1444 | |

| 1757/1787 | |

• Proclamation of independence from the Ottoman Empire | 28 November 1912 |

| 29 July 1913 | |

| 31 January 1925 | |

| 1 September 1928 | |

| 10 January 1946 | |

| 28 December 1976 | |

• 4th Republic of Albania | 29 April 1991 |

| 28 November 1998 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 28,748 km2 (11,100 sq mi) (140th) |

• Water (%) | 4.7 |

| Population | |

• 2023 census | 2,402,113[1] |

• Density | 83.5/km2 (216.3/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2019) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | high (74th) |

| Currency | Lek (ALL) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +355 |

| ISO 3166 code | AL |

| Internet TLD | .al |

Albania (/ælˈbeɪniə, ɔːl-/ a(w)l-BAY-nee-ə; Albanian: Shqipëri or Shqipëria),[a] officially the Republic of Albania (Albanian: Republika e Shqipërisë),[b] is a country in Southeast Europe. It is in the Balkans, on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to the northwest, Kosovo to the northeast, North Macedonia to the east and Greece to the south. With an area of 28,748 km2 (11,100 sq mi), it has a varied range of climatic, geological, hydrological and morphological conditions. Albania's landscapes range from rugged snow-capped mountains in the Albanian Alps and the Korab, Skanderbeg, Pindus and Ceraunian Mountains, to fertile lowland plains extending from the Adriatic and Ionian seacoasts. Tirana is the capital and largest city in the country, followed by Durrës, Vlorë, and Shkodër.

In ancient times, the Illyrians inhabited northern and central regions of Albania, whilst Epirotes inhabited the south. Several important ancient Greek colonies were also established on the coast. The Illyrian kingdom centered in what is now Albania was the dominant power before the Rise of Macedon.[6] In the 2nd century BC, the Roman Republic annexed the region, and after the division of the Roman Empire it became part of Byzantium. The first known Albanian autonomous principality, Arbanon, was established in the 12th century. The Kingdom of Albania, Principality of Albania and Albania Veneta were formed between the 13th and 15th centuries in different parts of the country, alongside other Albanian principalities and political entities. In the late 15th century, Albania became part of the Ottoman Empire. In 1912, the modern Albanian state declared independence. In 1939, Italy invaded the Kingdom of Albania, which became Greater Albania, and then a protectorate of Nazi Germany during World War II.[7] After the war, the People's Socialist Republic of Albania was formed, which lasted until the Revolutions of 1991 concluded with the fall of communism in Albania and eventually the establishment of the current Republic of Albania.

Since its independence in 1912, Albania has undergone a diverse political evolution, transitioning from a monarchy to a communist regime before becoming a sovereign parliamentary constitutional republic. Governed by a constitution prioritizing the separation of powers, the country's political structure includes a parliament, a ceremonial president, a functional prime minister and a hierarchy of courts. Albania is a developing country with an upper-middle income economy driven by the service sector, with manufacturing and tourism also playing significant roles.[8] After the dissolution of its communist system the country shifted from centralized planning to an open market economy.[9] Albanian citizens benefit from universal health care access and free primary and secondary education.

Etymology

The historical origins of the term "Albania" can be traced back to medieval Latin, with its foundations believed to be associated with the Illyrian tribe of the Albani. This connection gains further support from the work of the Ancient Greek geographer Ptolemy during the 2nd century AD, where he included the settlement of Albanopolis situated to the northeast of Durrës.[10][11] The presence of a medieval settlement named Albanon or Arbanon hints at the possibility of historical continuity. The precise relationship among these historical references and the question of whether Albanopolis was synonymous with Albanon remain subjects of scholarly debate.[12]

The Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates, in his 11th-century historical account, provides the earliest undisputed reference to the Albanians, when he mentions them having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1079.[13] He also identifies the Arbanitai as subjects of the Duke of Dyrrachium.[14] In the Middle Ages, Albania was denoted as Arbëri or Arbëni by its inhabitants, who identified themselves as Arbëreshë or Arbëneshë.[15] Albanians employ the terms Shqipëri or Shqipëria for their nation, designations that trace their historical origins to the 14th century.[16] But only in the late 17th and early 18th centuries did these terms gradually supersede Arbëria and Arbëreshë among Albanians.[16][17] These two expressions are widely interpreted to symbolise "Children of the Eagles" and "Land of the Eagles".[18][19]

History

Prehistory

Mesolithic habitation in Albania has been evidenced in several open air sites which during that period were close to the Adriatic coastline and in cave sites. Mesolithic objects found in a cave near Xarrë include flint and jasper objects along with fossilised animal bones, while those discoveries at Mount Dajt comprise bone and stone tools similar to those of the Aurignacian culture.[20] The Neolithic era in Albania began around 7000 BC and is evidenced in finds which indicate domestication of sheep and goats and small-scale agriculture. A part of the Neolithic population may have been the same as the Mesolithic population of the southern Balkans like in the Konispol cave where the Mesolithic stratum co-exists with Pre-Pottery Neolithic finds. Cardium pottery culture appears in coastal Albania and across the Adriatic after 6500 BC, while the settlements of the interior took part in the processes which formed Starčevo culture.[21] The Albanian bitumen mines of Selenicë provide early evidence of bitumen exploitation in Europe, dating to Late Neolithic Albania (from 5000 BC), when local communities used it as pigment for ceramic decoration, waterproofing, and adhesive for reparing broken vessels. The bitumen of Selenicë circulated towards eastern Albania from the early 5th millennium BC. First evidence of its overseas trade export comes from Neolithic and Bronze Age southern Italy. The high-quality bitumen of Selenicë has been exploited throughout all the historical ages since the Late Neolithic era until today.[22]

The Indo-Europeanization of Albania in the context of the IE-ization of the western Balkans began after 2800 BC. The presence of the Early Bronze Age tumuli in the vicinity of later Apollonia dates to 2679±174 calBC (2852-2505 calBC). These burial mounds belong to the southern expression of the Adriatic-Ljubljana culture (related to later Cetina culture) which moved southwards along the Adriatic from the northern Balkans. The same community built similar mounds in Montenegro (Rakića Kuće) and northern Albania (Shtoj).[23] The first archaeogenetic find related to the IE-ization of Albania involves a man with predominantly Yamnaya ancestry buried in a tumulus of northeastern Albania which dates to 2663–2472 calBC.[24] During the Middle Bronze Age, Cetina culture sites and finds appear in Albania. Cetina culture moved southwards across the Adriatic from the Cetina valley of Dalmatia. In Albania, Cetina finds are concentrated around southern Lake Shkodër and appear typically in tumulus cemeteries like in Shkrel and Shtoj and hillforts like Gajtan (Shkodër) as well as cave sites like Blaz, Nezir and Keputa (central Albania) and lake basin sites like Sovjan (southeastern Albania).[25]

Antiquity

The incorporated territory of Albania was historically inhabited by Indo-European peoples, amongst them numerous Illyrian and Epirote tribes. There were also several Greek colonies. The territory referred to as Illyria corresponded roughly to the area east of the Adriatic Sea in the Mediterranean Sea extending in the south to the mouth of the Vjosë.[26][27] The first account of the Illyrian groups comes from Periplus of the Euxine Sea, a Greek text written in the 4th century BC.[28] The Bryges were also present in central Albania, while the south was inhabited by the Epirote Chaonians, whose capital was at Phoenice.[28][29][30] Other colonies such as Apollonia and Epidamnos were established by Greek city-states on the coast by the 7th century BC.[28][31][32]

The Illyrian Taulanti were a powerful Illyrian tribe that were among the earliest recorded tribes in the area. They lived in an area that corresponds much of present-day Albania. Together with the Dardanian ruler Cleitus, Glaucias, the ruler of the Taulantian kingdom, fought against Alexander the Great at the Battle of Pelium in 335 BC. As the time passed, the ruler of Ancient Macedonia, Cassander of Macedon captured Apollonia and crossed the river Genusus (Albanian: Shkumbin) in 314 BC. A few years later Glaucias laid siege to Apollonia and captured the Greek colony of Epidamnos.[33]

The Illyrian Ardiaei tribe, centred in Montenegro, ruled over most of the territory of northern Albania. Their Ardiaean Kingdom reached its greatest extent under King Agron, the son of Pleuratus II. Agron extended his rule over other neighbouring tribes as well.[34] Following Agron's death in 230 BC, his wife, Teuta, inherited the Ardiaean kingdom. Teuta's forces extended their operations further southwards to the Ionian Sea.[35] In 229 BC, Rome declared war[36] on the kingdom for extensively plundering Roman ships. The war ended in Illyrian defeat in 227 BC. Teuta was eventually succeeded by Gentius in 181 BC.[37] Gentius clashed with the Romans in 168 BC, initiating the Third Illyrian War. The conflict resulted in Roman conquest of the region by 167 BC. The Romans split the region into three administrative divisions.[38]

Middle Ages

The Roman Empire was split in 395 upon the death of Theodosius I into an Eastern and Western Roman Empire in part because of the increasing pressure from threats during the Barbarian Invasions. From the 6th century into the 7th century, the Slavs crossed the Danube and largely absorbed the indigenous Greeks, Illyrians and Thracians in the Balkans; thus, the Illyrians were mentioned for the last time in historical records in the 7th century.[39][40]

In the 11th century, the Great Schism formalised the break of communion between the Eastern Orthodox and Western Catholic Church that is reflected in Albania through the emergence of a Catholic north and Orthodox south. The Albanian people inhabited the west of Lake Ochrida and the upper valley of River Shkumbin and established the Principality of Arbanon in 1190 under the leadership of Progon of Kruja.[41] The realm was succeeded by his sons Gjin and Dhimitri.

Upon the death of Dhimiter, the territory came under the rule of the Albanian-Greek Gregory Kamonas and subsequently under the Golem of Kruja.[42][43][44] In the 13th century, the principality was dissolved.[45][46][47] Arbanon is considered to be the first sketch of an Albanian state, that retained a semi-autonomous status as the western extremity of the Byzantine Empire, under the Byzantine Doukai of Epirus or Laskarids of Nicaea.[48]

Towards the end of the 12th and beginning of the 13th centuries, Serbs and Venetians started to take possession over the territory.[49] The ethnogenesis of the Albanians is uncertain; however, the first undisputed mention of Albanians dates back in historical records from 1079 or 1080 in a work by Michael Attaliates, who referred to the Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople.[50] At this point the Albanians were fully Christianised.

After the dissolution of Arbanon, Charles of Anjou concluded an agreement with the Albanian rulers, promising to protect them and their ancient liberties. In 1272, he established the Kingdom of Albania and conquered regions back from the Despotate of Epirus. The kingdom claimed all of central Albania territory from Dyrrhachium along the Adriatic Sea coast down to Butrint. A catholic political structure was a basis for the papal plans of spreading Catholicism in the Balkan Peninsula. This plan found also the support of Helen of Anjou, a cousin of Charles of Anjou. Around 30 Catholic churches and monasteries were built during her rule mainly in northern Albania.[51] Internal power struggles within the Byzantine Empire in the 14th century enabled Serbs' most powerful medieval ruler, Stefan Dusan, to establish a short-lived empire that included all of Albania except Durrës.[49] In 1367, various Albanian rulers established the Despotate of Arta. During that time, several Albanian principalities were created, notably the Principality of Albania, Principality of Kastrioti, Lordship of Berat and Principality of Dukagjini. In the first half of the 15th century, the Ottoman Empire invaded most of Albania, and the League of Lezhë was held under Skanderbeg as a ruler, who became the national hero of the Albanian medieval history.

Ottoman Empire

With the fall of Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire continued an extended period of conquest and expansion with its borders going deep into Southeast Europe. They reached the Albanian Ionian Sea Coast in 1385 and erected their garrisons across Southern Albania in 1415 and then occupied most of Albania in 1431.[52][53] Thousands of Albanians consequently fled to Western Europe, particularly to Calabria, Naples, Ragusa and Sicily, whereby others sought protection at the often inaccessible Mountains of Albania.[54][55] The Albanians, as Christians, were considered an inferior class of people, and as such they were subjected to heavy taxes among others by the Devshirme system that allowed the Sultan to collect a requisite percentage of Christian adolescents from their families to compose the Janissary.[56] The Ottoman conquest was also accompanied with the gradual process of Islamisation and the rapid construction of mosques.

A prosperous and longstanding revolution erupted after the formation of the League of Lezhë until the fall of Shkodër under the leadership of Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg, who consistently defeated major Ottoman armies led by Sultans Murad II and Mehmed II. Skanderbeg managed to unite several of the Albanian principalities, amongst them the Arianitis, Dukagjinis, Zaharias and Thopias, and establish a centralised authority over most of the non-conquered territories, becoming the Lord of Albania.[57] The Ottoman Empire's expansion ground to a halt during the time that Skanderbeg's forces resisted, and he has been credited with being one of the main reasons for the delay of Ottoman expansion into Western Europe, giving the Italian principalities more time to better prepare for the Ottoman arrival.[58] However, the failure of most European nations, with the exception of Naples, in giving him support, along with the failure of Pope Pius II's plans to organize a promised crusade against the Ottomans meant that none of Skanderbeg's victories permanently hindered the Ottomans from invading the Western Balkans.[59][60]

Despite his brilliance as a military leader, Skanderbeg's victories were only delaying the final conquests. The constant Ottoman invasions caused enormous destruction to Albania, greatly reducing the population and destroying flocks of livestock and crops. Besides surrender, there was no possible way Skanderbeg would be able to halt the Ottoman invasions despite his successes against them. His manpower and resources were insufficient, preventing him from expanding the war efforts and driving the Turks from the Albanian borders. Albania was therefore doomed to face an unending series of Ottoman attacks until it eventually fell years after his death.[61]

When the Ottomans were gaining a firm foothold in the region, Albanian towns were organised into four principal sanjaks. The government fostered trade by settling a sizeable Jewish colony of refugees fleeing persecution in Spain. The city of Vlorë saw passing through its ports imported merchandise from Europe such as velvets, cotton goods, mohairs, carpets, spices and leather from Bursa and Constantinople. Some citizens of Vlorë even had business associates throughout Europe.[62]

The phenomenon of Islamisation among the Albanians became primarily widespread from the 17th century and continued into the 18th century.[63] Islam offered them equal opportunities and advancement within the Ottoman Empire. However, motives for conversion were, according to some scholars, diverse depending on the context though the lack of source material does not help when investigating such issues.[63] Because of increasing suppression of Catholicism, most Catholic Albanians converted in the 17th century, while Orthodox Albanians followed suit mainly in the following century.

Since the Albanians were seen as strategically important, they made up a significant proportion of the Ottoman military and bureaucracy. Many Muslim Albanians attained important political and military positions and culturally contributed to the broader Muslim world.[63] Enjoying this privileged position, they held various high administrative positions with over two dozen Albanian Grand Viziers. Others included members of the prominent Köprülü family, Zagan Pasha, Muhammad Ali of Egypt and Ali Pasha of Tepelena. Furthermore, two sultans, Bayezid II and Mehmed III, both had mothers of Albanian origin.[62][64][65]

Rilindja

The Albanian Renaissance was a period with its roots in the late 18th century and continuing into the 19th century, during which the Albanian people gathered spiritual and intellectual strength for an independent cultural and political life within an independent nation. Modern Albanian culture flourished too, especially Albanian literature and arts, and was frequently linked to the influences of the Romanticism and Enlightenment principles.[67] Prior to the rise of nationalism, Ottoman authorities suppressed any expression of national unity or conscience by the Albanian people.

The victory of Russia over the Ottoman Empire following the Russian-Ottoman Wars resulted the execution of the Treaty of San Stefano which assigned Albanian-populated lands to their Slavic and Greek neighbours. However, the United Kingdom and Austro-Hungarian Empire consequently blocked the arrangement and caused the Treaty of Berlin. From this point, Albanians started to organise themselves with the goal to protect and unite the Albanian-populated lands into a unitary nation, leading to the formation of the League of Prizren. The league had initially the assistance of the Ottoman authorities whose position was based on the religious solidarity of Muslim people and landlords connected with the Ottoman administration. They favoured and protected the Muslim solidarity and called for defence of Muslim lands simultaneously constituting the reason for titling the league Committee of the Real Muslims.[68]

Approximately 300 Muslims participated in the assembly composed by delegates from Bosnia, the administrator of the Sanjak of Prizren as representatives of the central authorities and no delegates from Vilayet of Scutari.[69] Signed by only 47 Muslim deputies, the league issued the Kararname that contained a proclamation that the people from northern Albania, Epirus and Bosnia and Herzegovina are willing to defend the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire by all possible means against the troops of Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro.[70]

Ottomans authorities cancelled their assistance when the league, under Abdyl Frashëri, became focused on working towards Albanian autonomy and requested merging four vilayets, including Kosovo, Shkodër, Monastir and Ioannina, into a unified vilayet, the Albanian Vilayet. The league used military force to prevent the annexing areas of Plav and Gusinje assigned to Montenegro. After several successful battles with Montenegrin troops, such as the Battle of Novšiće, the league was forced to retreat from their contested regions. The league was later defeated by the Ottoman army sent by the sultan.[71]

Independence

Albania declared independence from the Ottoman Empire on 28 November 1912, accompanied by the establishment of the Senate and Government by the Assembly of Vlorë on 4 December 1912.[72][73][74][75] Its sovereignty was recognized by the Conference of London. On 29 July 1913, the Treaty of London delineated the borders of the country and its neighbors, leaving many Albanians outside Albania, predominantly partitioned between Montenegro, Serbia, and Greece.[76]

Headquartered in Vlorë, the International Commission of Control was established on 15 October 1913 to take care of the administration of Albania until its own political institutions were in order.[77][78] The International Gendarmerie was established as the Principality of Albania's first law enforcement agency. In November, the first gendarmerie members arrived in the country. Prince of Albania Wilhelm of Wied (Princ Vilhelm Vidi) was selected as the first prince of the principality.[79] On 7 March, he arrived in the provisional capital of Durrës and began to organize his government, appointing Turhan Pasha Përmeti to form the first Albanian cabinet.

In November 1913, the Albanian pro-Ottoman forces had offered the throne of Albania to the Ottoman war minister of Albanian origin, Ahmed Izzet Pasha.[80] The pro-Ottoman peasants believed that the new regime was a tool of the six Christian Great Powers and local landowners, who owned half of the arable land.[81]

In February 1914, the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus was proclaimed in Gjirokastër by the local Greek population against incorporation to Albania. This initiative was short-lived, and in 1921 the southern provinces were incorporated into the Albanian Principality.[82][83] Meanwhile, the revolt of Albanian peasants against the new regime erupted under the leadership of the group of Muslim clerics gathered around Essad Pasha Toptani, who proclaimed himself the savior of Albania and Islam.[84][85] To gain the support of the Mirdita Catholic volunteers from northern Albania, Prince Wied appointed their leader, Prênk Bibë Doda, foreign minister of the Principality of Albania. In May and June 1914, the International Gendarmerie was joined by Isa Boletini and his men, mostly from Kosovo,[86] and the rebels defeated northern Mirdita Catholics, capturing most of Central Albania by the end of August 1914.[87] Prince Wied's regime collapsed, and he left the country on 3 September 1914.[88]

First Republic

The interwar period in Albania was marked by persistent economic and social difficulties, political instability and foreign interventions.[89][90] After World War I, Albania lacked an established government and internationally recognized borders, rendering it vulnerable to neighboring entities such as Greece, Italy, and Yugoslavia, all of which sought to expand their influence.[89] This led to political uncertainty, highlighted in 1918 when the Congress of Durrës sought Paris Peace Conference protection but was denied, further complicating Albania's position on the international stage. Territorial tensions escalated as Yugoslavia, particularly Serbia, sought control of northern Albania, while Greece aimed dominance in southern Albania. The situation deteriorated in 1919 when the Serbs launched attacks on Albanian inhabitants, among others in Gusinje and Plav, resulting in massacres and large-scale displacement.[89][91][92] Meanwhile, Italian influence continued to expand during this time, driven by economic interests and political ambitions.[90][93]

Fan Noli, renowned for his idealism, became prime minister in 1924, with a vision to institute a Western-style constitutional government, abolish feudalism, counter Italian influence, and enhance critical sectors, including infrastructure, education and healthcare.[89] He faced resistance from former allies, who had assisted in the removal of Zog from power, and struggled to secure foreign aid to implement his agenda. Noli's decision to establish diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union, an adversary of the Serbian elite, ignited allegations of bolshevism from Belgrade.[89] This in turn led to increased pressure from Italy and culminated in Zog's restoration to authority.

Kingdom

In 1928, Zog transitioned Albania from a republic to a monarchy, assuming the title of King Zog I. He garnered backing from Fascist Italy and made other constitutional changes, dissolving the Senate and establishing a unicameral National Assembly while preserving his own authoritative powers.[89]

In 1939, Italy under Benito Mussolini launched a military invasion of Albania, resulting in the exile of Zog and the creation of an Italian protectorate, which was recognized only by the allies of Italy.[94][95] As World War II progressed, Italy aimed to expand its territorial dominion in the Balkans, including territorial claims on regions of Greece (Chameria), Macedonia, Montenegro, and Kosovo. These ambitions laid the foundations of a Greater Albania, which aimed to unite all areas with Albanian-majority populations into a single country.[96] In 1943, as Italy's control declined, Nazi Germany assumed control of Albania, subjecting Albanians to forced labor, economic exploitation, and repression, under the German occupation of Albania.[97] The tide shifted in 1944 when Albanian partisan forces, under the leadership of Enver Hoxha and other communist leaders, successfully liberated Albania from German occupation.[98]

Communism

The establishment of the People's Republic of Albania under the leadership of Enver Hoxha was a significant epoch in modern Albanian history.[99] Hoxha's regime embraced Marxist–Leninist ideologies and implemented authoritarian policies, including prohibition of religious practices, severe restrictions on travel, and abolition of private property rights.[100] It was also defined by a persistent pattern of purges, extensive repression, instances of betrayal, and hostility to external influences.[100] Any form of opposition or resistance to his rule was met with expeditious and severe consequences, such as internal exile, extended imprisonment, and execution.[100] The regime confronted a multitude of challenges, including widespread poverty, illiteracy, health crises and gender inequality.[98] In response, Hoxha initiated a modernization initiative aimed at attaining economic and social liberation and transforming Albania into an industrial society.[98] The regime placed a high priority on the diversification of the economy through Soviet-style industrialization, comprehensive infrastructure development such as the introduction of a transformative railway system, expansion of education and healthcare services, elimination of adult illiteracy, and targeted advancements in areas such as women's rights.[101][102][103][104]

Albania's diplomatic history under Hoxha was characterized by notable conflicts.[89] Initially aligned with Yugoslavia as a satellite state, the relationship deteriorated as Yugoslavia aimed to incorporate Albania within its territory.[89] Subsequently, Albania established relations with the Soviet Union and engaged trade agreements with other Eastern European countries, but experienced disagreements over Soviet policies, leading to strained ties with Moscow and diplomatic separation in 1961.[89] Simultaneously, tensions with the West heightened due to Albania's refusal to hold free elections and allegations of Western support for anti-communist uprisings. Albania's enduring partnership was with China; it sided with Beijing during the Sino-Soviet conflict, resulting in severed ties with the Soviet Union and withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact in response to the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. But their relations stagnated in 1970, prompting both to reassess their commitment, and Albania actively reduced its dependence on China.[89]

Under Hoxha's regime, Albania underwent a widespread campaign targeting religious clergy of various faiths, resulting in public persecution and executions, particularly targeting Muslims, Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox adherents.[89] In 1946, religious estates underwent nationalization, coinciding with the closure or transformation of religious institutions into various other purposes.[89] This culminated in 1976, when Albania became the world's first constitutionally atheist state.[106] Under this regime, Albanians were forced to renounce their religious beliefs, adopt a secular way of life, and embrace socialist ideology.[89][106]

Fourth Republic

After four decades of communism paired with the revolutions of 1989, Albania witnessed a notable rise in political activism, particularly among students, which led to a transformation in the prevailing order. After the first multi-party elections of 1991, the communist party maintained a stronghold in the parliament until its defeat in the parliamentary elections of 1992 directed by the Democratic Party.[107] Considerable economic and financial resources were devoted to pyramid schemes that were widely supported by the government. The schemes swept up somewhere between one sixth and one third of the population of the country.[108][109] Despite the International Monetary Fund's warnings, Sali Berisha defended the schemes as large investment firms, leading more people to redirect their remittances and sell their homes and cattle for cash to deposit in the schemes.[110]

The schemes began to collapse in late 1996, leading many of the investors to join initially peaceful protests against the government, requesting their money back. The protests turned violent in February 1997 as government forces responded by firing on the demonstrators. In March, the Police and Republican Guard deserted, leaving their armories open. These were promptly emptied by militias and criminal gangs. The resulting civil war caused a wave of evacuations of foreign nationals and refugees.[111]

The crisis led both Aleksandër Meksi and Sali Berisha to resign from office in the wake of the general election. In April 1997, Operation Alba, a U.N. peacekeeping force led by Italy, entered Albania with two goals: to assist with the evacuation of expatriates and secure the ground for international organizations. The main international organization involved was the Western European Union's multinational Albanian Police element, which worked with the government to restructure the judicial system and simultaneously the Albanian police.

Contemporary

After its communist system disintegrated, Albania embarked on an active path toward Westernization with the ambition to obtain membership in the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).[113] A notable milestone was reached in 2009, when the country attained membership in NATO, marking a pioneering achievement among the nations of Southeast Europe.[114][115] In adherence to its vision for further integration into the EU, it formally applied for membership on 28 April 2009.[116] Another milestone was reached on 24 June 2014, when the country was granted official candidate status.[117]

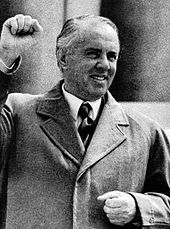

Edi Rama of the Socialist Party won both the 2013 and 2017 parliamentary elections. As prime minister, he implemented numerous reforms focused on modernizing the economy, as well as democratizing state institutions, including the judiciary and law enforcement. Unemployment has steadily declined, with Albania achieving the 4th-lowest unemployment rate in the Balkans.[118] Rama has also placed gender equality at the center of his agenda; since 2017 almost 50% of the ministers have been female, the largest number of women serving in the country's history.[119] During the 2021 parliamentary elections, the ruling Socialist Party led by Rama secured its third consecutive victory, winning nearly half of votes and enough seats in parliament to govern alone.[120][121]

On 26 November 2019, a 6.4 magnitude earthquake ravaged Albania, with the epicenter about 16 km (10 mi) southwest of the town of Mamurras.[122] The tremor was felt in Tirana and in places as far away as Taranto, Italy, and Belgrade, Serbia, while the most affected areas were the coastal city of Durrës and the village of Kodër-Thumanë.[123] Comprehensive response to the earthquake included substantial humanitarian aid from the Albanian diaspora and various countries around the world.[124]

On 9 March 2020, COVID-19 was confirmed to have spread to Albania.[125][126] From March to June 2020, the government declared a state of emergency as a measure to limit the virus's spread.[127][128][129] The country's COVID-19 vaccination campaign started on 11 January 2021, but as of 11 August 2021, the total number of vaccines administered in Albania was 1,280,239 doses.[130][131]

Environment

Geography

Albania lies along the Mediterranean Sea on the Balkan Peninsula in South and Southeast Europe, and has an area of 28,748 km2 (11,100 sq mi).[132] It is bordered by the Adriatic Sea to the west, Montenegro to the northwest, Kosovo to the northeast, North Macedonia to the east, Greece to the south, and the Ionian Sea to the southwest. It is between latitudes 42° and 39° N and longitudes 21° and 19° E. Geographic coordinates include Vërmosh at 42° 35' 34" northern latitude as the northernmost point, Konispol at 39° 40' 0" northern latitude as the southernmost, Sazan at 19° 16' 50" eastern longitude as the westernmost, and Vërnik at 21° 1' 26" eastern longitude as the easternmost.[133] Mount Korab, rising at 2,764 m (9,068.24 ft) above the Adriatic, is the highest point, while the Mediterranean Sea, at 0 m (0.00 ft), is the lowest. The country extends 148 km (92 mi) from east to west and around 340 km (211 mi) from north to south.

Albania has a diverse and varied landscape with mountains and hills that traverse its territory in various directions. The country is home to extensive mountain ranges, including the Albanian Alps in the north, the Korab Mountains in the east, the Pindus Mountains in the southeast, the Ceraunian Mountains in the southwest, and the Skanderbeg Mountains in the center. In the northwest is the Lake of Shkodër, Southern Europe's largest lake.[134] Toward the southeast emerges the Lake of Ohrid, one of the world's oldest continuously existing lakes.[135] Farther south, the expanse includes the Large and Small Lake of Prespa, some of the Balkans' highest lakes. Rivers rise mostly in the east and discharge into the Adriatic and Ionian Seas. The country's longest river, measured from mouth to source, is the Drin, which starts at the confluence of its two headwaters, the Black and White Drin. Of particular concern is the Vjosë, one of Europe's last intact large river systems.

Climate

The climate of Albania exhibits a distinguished level of variability and diversity due to the differences in latitude, longitude and altitude.[136][137] Albania experiences a Mediterranean and Continental climate, characterised by the presence of four distinct seasons.[138] According to the Köppen classification, Albania encompasses five primary climatic types, spanning from Mediterranean and subtropical in the western half to oceanic, continental and subarctic in the eastern half of the country.[139] The coastal regions along the Adriatic and Ionian Seas in Albania are acknowledged as the warmest areas, while the northern and eastern regions encompassing the Albanian Alps and the Korab Mountains are recognised as the coldest areas in the country.[140] Throughout the year, the average monthly temperatures fluctuate, ranging from −1 °C (30 °F) during the winter months to 21.8 °C (71.2 °F) in the summer months. Notably, the highest recorded temperature of 43.9 °C (111.0 °F) was observed in Kuçovë on 18 July 1973, while the lowest temperature of −29 °C (−20 °F) was recorded in Shtyllë, Librazhd on 9 January 2017.[141][142]

Albania receives most of the precipitation in winter months and less in summer months.[137] The average precipitation is about 1,485 millimetres (58.5 inches).[140] The mean annual precipitation ranges between 600 and 3,000 millimetres (24 and 118 inches) depending on geographical location.[138] The northwestern and southeastern highlands receive the intenser amount of precipitation, whilst the northeastern and southwestern highlands as well as the Western Lowlands the more limited amount.[140] The Albanian Alps in the far north of the country are considered to be among the most humid regions of Europe, receiving at least 3,100 mm (122.0 in) of rain annually.[140] Four glaciers within these mountains were discovered at a relatively low altitude of 2,000 metres (6,600 ft), which is extremely rare for such a southerly latitude.[143]

Biodiversity

A biodiversity hotspot, Albania possesses an exceptionally rich and contrasting biodiversity on account of its geographical location at the centre of the Mediterranean Sea and the great diversity in its climatic, geological and hydrological conditions.[144][145] Because of remoteness, the mountains and hills of Albania are endowed with forests, trees and grasses that are essential to the lives for a wide variety of animals, among others for two of the most endangered species of the country, the lynx and brown bear, as well as the wildcat, grey wolf, red fox, golden jackal, Egyptian vulture and golden eagle, the latter constituting the national animal of the country.[146][147][148][149]

The estuaries, wetlands and lakes are extraordinarily important for the greater flamingo, pygmy cormorant and the extremely rare and perhaps the most iconic bird of the country, the dalmatian pelican.[150] Of particular importance are the Mediterranean monk seal, loggerhead sea turtle and green sea turtle that use to nest on the country's coastal waters and shores.

In terms of phytogeography, Albania is part of the Boreal Kingdom and stretches specifically within the Illyrian province of the Circumboreal and Mediterranean Region. Its territory can be subdivided into four terrestrial ecoregions of the Palearctic realm namely within the Illyrian deciduous forests, Balkan mixed forests, Pindus Mountains mixed forests and Dinaric Mountains mixed forests.[151][152]

Approximately 3,500 different species of plants can be found in Albania which refers principally to a Mediterranean and Eurasian character. The country maintains a vibrant tradition of herbal and medicinal practices. At the minimum 300 plants growing locally are used in the preparation of herbs and medicines.[153] The trees within the forests are primarily fir, oak, beech and pine.

Conservation

Albania has been an active participant in numerous international agreements and conventions aimed at strengthing its commitment to the preservation and sustainable management of biological diversity. Since 1994, the country is a party to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and its associated Cartagena and Nagoya Protocols.[154] To uphold these commitments, it has developed and implemented a comprehensive National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP).[154] Furthermore, Albania has established a partnership with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), advancing its conservation efforts on both national and international scales. Guided by the IUCN, the country has made substantial progress in the foundation of protected areas within its boundaries, encompassing 12 national parks among others Butrint, Karaburun-Sazan, Llogara, Prespa and Vjosa.[155]

As a signatory to the Ramsar Convention, Albania has granted special recognition upon four wetlands, designating them as Wetlands of International Importance, including Buna-Shkodër, Butrint, Karavasta and Prespa.[156] The country's dedication to protection extends further into the sphere of UNESCO's World Network of Biosphere Reserves, operating within the framework of the Man and the Biosphere Programme, evidenced by its engagement in the Ohrid-Prespa Transboundary Biosphere Reserve.[157][158] Furthermore, Albania is host to two natural World Heritage Sites, which encompass the Ohrid region and both the Gashi River and Rrajca as part of Ancient and Primeval Beech Forests of the Carpathians and Other Regions of Europe.[159]

Protected areas

The protected areas of Albania are areas designated and managed by the Albanian government. There are 12 national parks, 4 ramsar sites, 1 biosphere reserve and 786 other types of conservation reserves in Albania.[155][160] Located in the north, the Albanian Alps National Park, comprising the former Theth National Park and Valbonë Valley National Park, is surrounded amidst the towering peaks of the Albanian Alps. In the east, portions of the rugged Korab, Nemërçka and Shebenik Mountains are conserved within the boundaries of Fir of Hotovë-Dangëlli National Park, Shebenik National Park and Prespa National Park, with the latter encompassing Albania's share of the Great and Small Lakes of Prespa.

To the south, the Ceraunian Mountains define the Albanian Ionian Sea Coast, shaping the landscape of Llogara National Park, which extends into the Karaburun Peninsula, forming the Karaburun-Sazan Marine Park. Further southward lies Butrint National Park, occupying a peninsula surrounded by the Lake of Butrint and the Channel of Vivari. In the west, stretching along the Albanian Adriatic Sea Coast, the Divjakë-Karavasta National Park boasts the extensive Lagoon of Karavasta, one of the largest lagoon systems in the Mediterranean Sea. Notably, Europe's first wild river national park, Vjosa National Park, safeguards the Vjosa River and its primary tributaries, which originates in the Pindus Mountains and flows to the Adriatic Sea. Dajti Mountain National Park, Lurë-Dejë Mountain National Park and Tomorr Mountain National Park protect the mountainous terrain of the center of Albania, including the Tomorr and Skanderbeg Mountains.

Environmental issues

Environmental issues in Albania notably encompass air and water pollution, climate change impacts, waste management shortcomings, biodiversity loss and imperative for nature conservation.[161][162] Climate change is predicted to exert significant impacts on the quality of life in Albania.[163] The country is recognised as vulnerable to climate change impacts, ranked 79 among 181 countries in the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index of 2020.[164] Factors that account for the country's vulnerability to climate change risks include geological and hydrological hazards, including earthquakes, flooding, fires, landslides, torrential rains, river and coastal erosion.[165][166]

As a party to the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement, Albania is committed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 45% and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 which, along with national policies, will help to mitigate the impacts of the climate change.[167] The country has a moderate and improving performance in the Environmental Performance Index with an overall ranking of 62 out of 180 countries in 2022.[168] Albania's ranking has, however, decreased since its highest placement at position 15 in the Environmental Performance Index of 2012.[169] In 2019, Albania had a Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.77 from 10, ranking it 64th globally out of 172 countries.[170]

Politics

|

|

| Bajram Begaj President |

Edi Rama Prime Minister |

Since declaring independence in 1912, Albania has experienced a significant political transformation, traversing through distinct periods that included a monarchical rule, a communist regime and the eventual establishment of a democratic order.[171] In 1998, Albania transitioned into a sovereign parliamentary constitutional republic, marking a fundamental milestone in its political evolution.[172] Its governance structure operates under a constitution that serves as the principal document of the country.[173] The constitution is grounded in the principle of the separation of powers, with three arms of government that encompass the legislative embodied in the Parliament, the executive led by the President as the ceremonial head of state and the Prime Minister as the functional head of government, and the judiciary with a hierarchy of courts, including the constitutional and supreme courts as well as multiple appeal and administrative courts.[172]

Albania's legal system is structured to protect its people's political rights, regardless of their ethnic, linguistic, racial, or religious affiliations.[172][174] Despite these principles, there are significant human rights concerns in Albania that demand attention.[175] These concerns include issues related to the independence of the judiciary, the absence of a free media sector and the enduring problem of corruption within various governmental bodies, law enforcement agencies and other institutions.[175] As Albania pursues its path toward EU membership, active efforts are being made to achieve substantial improvements in these areas to align with EU criteria and standards.[174]

Foreign relations

Emerging from decades of isolation during the communism, Albania has adopted a foreign policy orientation centered on active cooperation and engagement in international affairs. At the core of Albania's foreign policies lie a set of objectives, which encompass the commitment to protect its sovereignty and territorial integrity, the cultivation of diplomatic ties with other countries, advocating for international recognition of Kosovo, addressing the concerns related to the expulsion of Cham Albanians, pursuing Euro-Atlantic integration and protecting the rights of the Albanians in Kosovo, Greece, Italy, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and the diaspora.[177]

The external affairs of Albania underscore the country's dedication to regional stability and integration into major international institutions.[178] Albania became a member of the United Nations (UN) in 1955, shortly after emerging from a period of isolation during the communist era.[179] The country reached a major achievement in its foreign policy by securing membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 2009.[180][181] Since obtaining candidate status in 2014, the country has also embarked on a comprehensive reform agenda to align itself with European Union (EU) accession standards, with the objective of becoming an EU member state.[117]

Albania and Kosovo maintain a fraternal relationship strengthened by their substantial cultural, ethnical and historical ties.[182] Both countries foster enduring diplomatic ties, with Albania actively supporting Kosovo's development and international integration efforts.[182] Its fundamental contribution to Kosovo's path to independence is underscored by its early recognition of Kosovo's sovereignty in 2008.[183] Furthermore, both governments hold annual joint meetings, displayed by the inaugural meeting in 2014, which serves as an official platform to enhance bilateral cooperation and reinforce their joint commitment to policies that promote the stability and prosperity of the broader Albanian region.[182]

Military

The Albanian Armed Forces consist of Land, Air and Naval Forces and constitute the military and paramilitary forces of the country. They are led by a commander-in-chief under the supervision of the Ministry of Defence and by the President as the supreme commander during wartime. However, in times of peace its powers are executed through the Prime Minister and the Defence Minister.[184]

The chief purpose of the armed forces of Albania is the defence of the independence, the sovereignty and the territorial integrity of the country, as well as the participation in humanitarian, combat, non-combat and peace support operations.[184] Military service is voluntary since 2010 with the age of 19 being the legal minimum age for the duty.[185][186]

Albania has committed to increase the participations in multinational operations.[187] Since the fall of communism, the country has participated in six international missions but only one United Nations mission in Georgia, where it sent three military observers. Since February 2008, Albania has participated officially in NATO's Operation Active Endeavor in the Mediterranean Sea.[188] It was invited to join NATO on 3 April 2008, and it became a full member on 2 April 2009.[189]

Albania reduced the number of active troops from 65,000 in 1988 to 14,500 in 2009.[190][191] The military now consists mainly of a small fleet of aircraft and sea vessels. Increasing the military budget was one of the most important conditions for NATO integration. As of 1996 military spending was an estimated 1.5% of the country's GDP, only to peak in 2009 at 2% and fall again to 1.5%.[192]

Administrative divisions

Albania is defined within a territorial area of 28,748 km2 (11,100 sq mi) in the Balkan Peninsula. It is informally divided into three regions, the Northern, Central and Southern Regions. Since its Declaration of Independence in 1912, Albania has reformed its internal organization 21 times. Presently, the primary administrative units are the twelve constituent counties (qarqe/qarqet), which hold equal status under the law.[193] Counties had previously been used in the 1950s and were recreated on 31 July 2000 to unify the 36 districts (rrathë/rrathët) of that time.[194][195] The largest county in Albania by population is Tirana County with over 800,000 people. The smallest county, by population, is Gjirokastër County with over 70,000 people. The largest county, by area, is Korçë County encompassing 3,711 square kilometres (1,433 sq mi) of the southeast of Albania. The smallest county, by area, is Durrës County with an area of 766 square kilometres (296 sq mi) in the west of Albania.

The counties are made up of 61 second-level divisions known as municipalities (bashki/bashkia).[196] The municipalities are the first level of local governance, responsible for local needs and law enforcement.[197][198][199] They unified and simplified the previous system of urban and rural municipalities or communes (komuna/komunat) in 2015.[200][201] For smaller issues of local government, the municipalities are organized into 373 administrative units (njësia/njësitë administrative). There are also 2980 villages (fshatra/fshatrat), neighborhoods or wards (lagje/lagjet), and localities (lokalitete/lokalitetet) previously used as administrative units.

| Emblem | County | Capital | Area (km2) |

Population (2020) | HDI (2019) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berat | Berat | 1,798 | 122,003 | 0.782 | |||||||||||||||

| Dibër | Peshkopi | 2,586 | 115,857 | 0.754 | |||||||||||||||

| Durrës | Durrës | 766 | 290,697 | 0.802 | |||||||||||||||

| Elbasan | Elbasan | 3,199 | 270,074 | 0.784 | |||||||||||||||

| Fier | Fier | 1,890 | 289,889 | 0.767 | |||||||||||||||

| Gjirokastër | Gjirokastër | 2,884 | 59,381 | 0.794 | |||||||||||||||

| Korçë | Korçë | 3,711 | 204,831 | 0.790 | |||||||||||||||

| Kukës | Kukës | 2,374 | 75,428 | 0.749 | |||||||||||||||

| Lezhë | Lezhë | 1,620 | 122,700 | 0.769 | |||||||||||||||

| Shkodër | Shkodër | 3,562 | 200,007 | 0.784 | |||||||||||||||

| Tirana | Tirana | 1,652 | 906,166 | 0.820 | |||||||||||||||

| Vlorë | Vlorë | 2,706 | 188,922 | 0.802 | |||||||||||||||

| References:[202][203] | |||||||||||||||||||

Economy

This section needs to be updated. (May 2023) |

Albania's transition from a socialist planned economy to a capitalist mixed economy has been largely successful.[204] The country has a developing mixed economy classified by the World Bank as an upper-middle income economy. In 2016, it had the fourth-lowest unemployment rate in the Balkans with an estimated value of 14.7%. Its largest trading partners are Italy, Greece, China, Spain, Kosovo and the United States. The lek (ALL) is the country's currency and is pegged at approximately 132.51 lek per euro.

The cities of Tirana and Durrës constitute the economic and financial heart of Albania due to their high population, modern infrastructure and strategic geographical location. The country's most important infrastructure facilities take course through both of the cities, connecting the north to the south as well as the west to the east. Among the largest companies are the petroleum Taçi Oil, Albpetrol, ARMO and Kastrati, the mineral AlbChrome, the cement Antea, the investment BALFIN Group and the technology Albtelecom, Vodafone, Telekom Albania and others.

In 2012, Albania's GDP per capita stood at 30% of the European Union average, while GDP (PPP) per capita was 35%.[205] In the first quarter of 2010, after the Great Recession, Albania was one of three countries in Europe to record economic growth.[206][207] The International Monetary Fund predicted 2.6% growth for Albania in 2010 and 3.2% in 2011.[208] According to Forbes, as of December 2016[update], the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was growing at 2.8%. The country had a trade balance of −9.7% and unemployment rate of 14.7%.[209] Foreign direct investment has increased significantly in recent years as the government has embarked on an ambitious programme to improve the business climate through fiscal and legislative reforms.

Primary sector

Agriculture in the country is based on small to medium-sized family-owned dispersed units. It remains a significant sector of the economy of Albania. It employs 41%[210] of the population, and about 24.31% of the land is used for agricultural purposes. One of the earliest farming sites in Europe has been found in the southeast of the country.[211] As part of the pre-accession process of Albania to the European Union, farmers are being aided through IPA funds to improve Albanian agriculture standards.[212]

Albania produces significant amounts of fruits (apples, olives, grapes, oranges, lemons, apricots, peaches, cherries, figs, sour cherries, plums, and strawberries), vegetables (potatoes, tomatoes, maize, onions, and wheat), sugar beets, tobacco, meat, honey, dairy products, traditional medicine and aromatic plants. Further, the country is a worldwide significant producer of salvia, rosemary and yellow gentian.[213] The country's proximity to the Ionian Sea and the Adriatic Sea give the underdeveloped fishing industry great potential. The World Bank and European Community economists report that, Albania's fishing industry has good potential to generate export earnings because prices in the nearby Greek and Italian markets are many times higher than those in the Albanian market. The fish available off the coasts of the country are carp, trout, sea bream, mussels and crustaceans.

Albania has one of Europe's longest histories of viticulture.[214] Today's region was one of the few places where vine was naturally grown during the ice age. The oldest found seeds in the region are 4,000 to 6,000 years old.[215] In 2009, the nation produced an estimated 17,500 tonnes of wine.[216]

Secondary sector

Albania's secondary sector has undergone many changes and diversification since the communist regime collapsed. It is very diversified, from electronics, manufacturing,[217] textiles, to food, cement, mining,[218] and energy. The Antea Cement plant in Fushë-Krujë is considered one of the nation's largest industrial greenfield investments.[219] Albanian oil and gas is one of the most promising, albeit strictly regulated, sectors of its economy. Albania has the second-largest oil deposits in the Balkan peninsula after Romania, and the largest oil reserves[220] in Europe. The Albpetrol company is owned by the Albanian state and monitors the state petroleum agreements in the country. The textile industry has seen an extensive expansion by approaching companies from the European Union (EU) in Albania. According to the Institute of Statistics (INSTAT), as of 2016[update], textile production had an annual growth of 5.3% and an annual turnover of around 1.5 billion euros.[221]

Albania is a significant minerals producer and ranks among the world's leading chromium producers and exporters.[222] The nation is also a notable producer of copper, nickel, and coal.[223] The Batra mine, Bulqizë mine, and Thekna mine are among the most recognized Albanian mines still in operation.

Tertiary sector

The tertiary sector represents the fastest growing sector of the country's economy. 36% of the population work in the service sector which contributes to 65% of the country's GDP.[224] Ever since the end of the 20th century, the banking industry is a major component of the tertiary sector and remains in good conditions overall due to privatisation and the commendable monetary policy.[225][224]

Previously one of the most isolated and controlled countries in the world, telecommunication industry represents nowadays another major contributor to the sector. It developed largely through privatisation and subsequent investment by both domestic and foreign investors.[224] Eagle, Vodafone and Telekom Albania are the leading telecommunications service providers in the country.

Tourism is recognised as an industry of national importance and has been steadily increasing since the beginnings of the 21st century.[226][227] It directly accounted for 8.4% of GDP in 2016 though including indirect contributions pushes the proportion to 26%.[228] In the same year, the country received approximately 4.74 million visitors mostly from across Europe and the United States as well.[229]

The increase of foreign visitors has been dramatic. Albania had only 500,000 visitors in 2005, and an estimated 4.2 million in 2012, an increase of 740 percent. In 2015, summer tourism increased by 25 percent from 2014, according to the country's tourism agency.[230] In 2011, Lonely Planet named Albania as a top travel destination,[231][failed verification] while The New York Times placed Albania as number 4 global tourist destination in 2014.[232]

The bulk of the tourist industry is concentrated along the Adriatic and Ionian Sea in the west of the country. But the Albanian Riviera in the southwest has the most scenic and pristine beaches; its coastline has a considerable length of 446 kilometres (277 miles).[233] The coast has a distinctive character, rich in varieties of virgin beaches, capes, coves, covered bays, lagoons, small gravel beaches, sea caves, and many landforms. Some parts of this seaside are very clean ecologically, including unexplored areas, which are very rare within the Mediterranean.[234] Other attractions include the mountainous areas such as the Albanian Alps, Ceraunian Mountains and Korab Mountains but also the historical cities of Berat, Durrës, Gjirokastër, Sarandë, Shkodër and Korçë.

Transport

Transportation in Albania is managed within the functions of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Energy and entities such as the Albanian Road Authority (ARRSH), responsible for the construction and maintenance of the highways and motorways in Albania, as well as the Albanian Aviation Authority (AAC), with the responsibility of coordinating civil aviation and airports in the country.

The international airport of Tirana is the premier air gateway to the country, and is also the principal hub for Albania's national flag carrier airline, Air Albania. The airport carried more than 3.3 million passengers in 2019 with connections to many destinations in other countries around Europe, Africa and Asia.[235] The country plans to progressively increase the number of airports especially in the south with possible locations in Sarandë, Gjirokastër and Vlorë.[236]

The highways and motorways in Albania are properly maintained and often still under construction and renovation. The Autostrada 1 (A1) is an integral transportation corridor and the country's longest motorway. It is planned to link Durrës on the Adriatic Sea across Pristina in Kosovo with the Pan-European Corridor X in Serbia.[237][238] The Autostrada 2 (A2) is part of the Adriatic–Ionian Corridor as well as the Pan-European Corridor VIII and connects Fier with Vlorë.[237] The Autostrada 3 (A3) is under construction and after its completion will connect Tirana and Elbasan with the Pan-European Corridor VIII. When all three corridors are completed, Albania will have an estimated 759 kilometres (472 mi) of highway, linking it with all neighboring countries.

Durrës is the busiest and largest seaport in the country, followed by Vlorë, Shëngjin and Sarandë. As of 2014[update], it is as one of the largest passenger ports on the Adriatic Sea, with annual passenger volume of about 1.5 million. The principal ports serve a system of ferries connecting Albania with islands and coastal cities in Croatia, Greece, and Italy.

The rail network is administered by the national railway company Hekurudha Shqiptare, which was extensively promoted by Hoxha. There has been considerable increase in private car ownership and bus usage while rail use decreased since the end of communism. A new railway line from Tirana and its airport to Durrës is planned. The location of this railway, connecting Albania's most populated urban areas, makes it an important economic development project.[239][240]

Infrastructure

Education

In Albania, education is secular, free, compulsory, and based on three levels.[241][242] The academic year is apportioned into two semesters, beginning in September or October and ending in June or July. Albanian is the primary language of instruction in the country's academic institutions.[242] The study of a first foreign language is mandatory and taught most often at elementary and bilingual schools.[243] Languages taught in schools are English, Italian, French and German.[243] Albania has a school life expectancy of 16 years and a literacy rate of 98.7%, with 99.2% for men and 98.3% for women.[244][245]

Compulsory primary education is divided into two levels, elementary and secondary school, from grade one to five and six to nine, respectively.[241] Pupils are required to attend school from the age six until they turn 16. Upon successful completion of primary education, all pupils are entitled to attend high schools, specializing in any field, including arts, sports, languages, sciences, and technology.[241]

Tertiary education is optional and has undergone a thorough reformation and restructuring in compliance with the principles of the Bologna Process. There are a significant number of private and public institutions of higher education in Albania's major cities.[246][242] Tertiary education is organized into three successive levels, the bachelor, master, and doctorate.

Health

The constitution of Albania guarantees its citizens equal, free, and universal health care.[248] The health care system is organized into primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare, and is in a process of modernization and development.[249][250] The life expectancy at birth in Albania is 77.8 years, ranking 37th in the world and surpassing several developed countries.[251] The average healthy life expectancy is 68.8 years, ranking 37th in the world.[252] The country's infant mortality rate was estimated at 12 per 1,000 live births in 2015. In 2000, the country had the world's 55th-best healthcare performance, as defined by the World Health Organization.[253]

Cardiovascular disease is the principal cause of death in Albania, accounting for 52% of deaths.[249] Accidents, injuries, malignant and respiratory diseases are other primary causes of death.[249] Neuropsychiatric disease has also increased due to recent demographic, social, and economic changes in the country.[249]

In 2009, Albania had a fruit and vegetable supply of 886 grams per capita per day, the fifth-highest supply in Europe.[254] Compared to other developed and developing countries, Albania has a relatively low rate of obesity, probably thanks to the Mediterranean diet.[255][256] According to World Health Organization data from 2016, 21.7% of adults in the country are clinically overweight, with a Body mass index (BMI) score of 25 or more.[257]

Energy

Due to its location and natural resources, Albania has a wide variety of energy resources, ranging from gas, oil, and coal to wind, solar, water, and other renewable sources.[258][259] According to the World Economic Forum's 2023 Energy Transition Index (ETI), the country ranked 21st globally, highlighting the progress in its energy transition agenda.[260] Currently, Albania's electricity generation sector depends on hydroelectricity, ranking fifth in the world in percentage terms.[261][262][263] The Drin, in the north, hosts four hydroelectric power stations, including Fierza, Koman, Skavica and Vau i Dejës. Two other power stations, such as the Banjë and Moglicë, are along the Devoll in the south.[264]

Albania has considerable oil deposits. It has the 10th-largest oil reserves in Europe and the 58th in the world.[265] The country's main petroleum deposits are located around the Albanian Adriatic Sea Coast and Myzeqe Plain within the Western Lowlands, where the country's largest reserve is located. Patos-Marinza, also located within the area, is the largest onshore oil field in Europe.[266] The Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), part of the planned Southern Gas Corridor, runs for 215 kilometres (134 miles) across Albania's territory before entering the Albanian Adriatic Sea Coast approximately 17 kilometres (11 miles) northwest of Fier.[267]

Albania's water resources are particularly abundant in all the regions of the country and comprise lakes, rivers, springs, and groundwater aquifers.[268] The country's available average quantity of fresh water is estimated at 129.7 cubic metres (4,580 cubic feet) per inhabitant per year, one of the highest rates in Europe.[269] According to data presented by the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation (JMP) in 2015, about 93% of the country's total population had access to improved sanitation.[270]

Media

The freedom of press and speech, and the right to free expression is guaranteed in the constitution of Albania.[271] Albania was ranked 84th on the Press Freedom Index of 2020 compiled by the Reporters Without Borders, with its score steadily declining since 2003.[272] Nevertheless, in the 2020 report of Freedom in the World, the Freedom House classified the freedoms of press and speech in Albania as partly free from political interference and manipulation.[273]

Radio Televizioni Shqiptar (RTSH) is the national broadcaster corporation of Albania operating numerous television and radio stations in the country.[274] The three major private broadcaster corporations are Top Channel, Televizioni Klan and Vizion Plus whose content are distributed throughout Albania and beyond its territory in Kosovo and other Albanian-speaking territories.[275]

Albanian cinema has its roots in the 20th century and developed after the country's declaration of independence.[276] The first movie theater exclusively devoted to showing motion pictures was built in 1912 in Shkodër.[276] During the Peoples Republic of Albania, Albanian cinema developed rapidly with the inauguration of the Kinostudio Shqipëria e Re in Tirana.[276] In 1953, the Albanian-Soviet epic film, the Great Warrior Skanderbeg, was released chronicling the life and fight of the medieval Albanian hero Skanderbeg. It went on to win the international prize at the 1954 Cannes Film Festival. In 2003, the Tirana International Film Festival was established, the largest film festival in the country. The Durrës Amphitheatre is host to the Durrës International Film Festival, the second largest film festival.

Technology

After the fall of communism in 1991, human resources in sciences and technology in Albania have drastically decreased. As of various reports, during 1991 to 2005 approximately 50% of the professors and scientists of the universities and science institutions in the country have left Albania.[277] In 2009, the government approved the National Strategy for Science, Technology and Innovation in Albania covering the period 2009 to 2015.[278] It aims to triple public spending on research and development to 0.6% of GDP and augment the share of GDE from foreign sources, including the framework programmes for research of the European Union, to the point where it covers 40% of research spending, among others. Albania was ranked 83rd in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[279][280]

Telecommunication represents one of the fastest growing and dynamic sectors in Albania.[281][282] Vodafone Albania, Telekom Albania and Albtelecom are the three large providers of mobile and internet in Albania.[281] As of the Electronic and Postal Communications Authority (AKEP) in 2018, the country had approximately 2.7 million active mobile users with almost 1.8 million active broadband subscribers.[283] Vodafone Albania alone served more than 931,000 mobile users, Telekom Albania had about 605,000 users and Albtelecom had more than 272,000 users.[283] In January 2023, Albania launched its first two satellites, Albania 1 and Albania 2, into orbit, in what was regarded as a milestone effort in monitoring the country's territory and identifying illegal activities.[284][285] Albanian-American engineer Mira Murati, the Chief Technology Officer of research organization OpenAI, played a substantial role in the development and launch of artificial intelligence services such as ChatGPT, Codex and DALL-E.[286][287][288] In December 2023, Prime Minister Edi Rama announced plans for collaboration between the Albanian government and ChatGPT, facilitated by discussions with Murati.[289][290] Rama emphasised the intention to streamline the alignment of Albanian laws with the regulations of the European Union, aiming to reduce costs associated with translation and legal services.[289]

Demography

According to the 2023 census, the Institute of Statistics (INSTAT) calculated the population of Albania to be 2,402,113.[1] The country's total fertility rate of 1.51 children born per woman is one of the lowest in the world.[275] Its population density stands at 259 inhabitants per square kilometre. The overall life expectancy at birth is 78.5 years; 75.8 years for males and 81.4 years for females.[275] The country is the 8th most populous country in the Balkans and ranks as the 137th most populous country in the world. The country's population rose steadily from 2.5 million in 1979 until 1989, when it peaked at 3.1 million.[291] Since then, the population has continually decreased every year.[292] It is forecast that the population will continue shrinking for the next decade at least, depending on the actual birth rate and the level of net migration.[293] In 2022, over 46,000 people migrated out of Albania, a 10% increase over the previous year.[292]

The explanation for the recent population decrease is the fall of communism in Albania in the late twentieth century. That period was marked by economic mass emigration from Albania to Greece, Italy and the United States. The migration affected the country's internal population distribution. It decreased particularly in the north and south, while it increased in the centre within the cities of Tirana and Durrës.[citation needed] Migration abroad has continued in recent years, particularly of the young and educated. As much as a third of those born in the country's borders now live outside of it, making Albania one of the countries with the highest rate of outmigration relative to its population in the world.[294][295] In 2022 the birth rate was 20% lower than in 2021, largely due to emigration of people of childbearing age.[296]

About 53.4% of the country's population lives in cities. The three largest counties by population account for half of the total population. Almost 30% of the total population is found in Tirana County followed by Fier County with 11% and Durrës County with 10%.[297] Over one million people are concentrated in Tirana and Durrës, making it the largest urban area in Albania.[298] Tirana is one of largest cities in the Balkan Peninsula and ranks seventh with a population about 400,000.

| # | City | Population | # | City | Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tirana | 418,495 | 11 | Kavajë | 20,192 | ||

| 2 | Durrës | 113,249 | 12 | Gjirokastër | 19,836 | ||

| 3 | Vlorë | 79,513 | 13 | Sarandë | 17,233 | ||

| 4 | Elbasan | 78,703 | 14 | Laç | 17,086 | ||

| 5 | Shkodër | 77,075 | 15 | Kukës | 16,719 | ||

| 6 | Fier | 55,845 | 16 | Patos | 15,937 | ||

| 7 | Korçë | 51,152 | 17 | Lezhë | 15,510 | ||

| 8 | Berat | 32,606 | 18 | Peshkopi | 13,251 | ||

| 9 | Lushnjë | 31,105 | 19 | Kuçovë | 12,654 | ||

| 10 | Pogradec | 20,848 | 20 | Krujë | 11,721 | ||

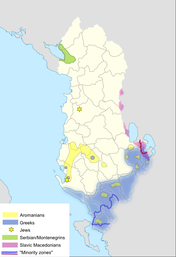

Minorities

This section needs to be updated. (May 2023) |

Albania recognises nine national or cultural minorities: Aromanian, Greek, Macedonian, Montenegrin, Serb, Roma, Egyptian, Bosnian and Bulgarian peoples.[300] Other Albanian minorities are the Gorani people and Jews.[301] Contrary to official statistics that show an over 97 per cent Albanian majority in the country, minority groups (such as Greeks, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Roma and Aromanians) have frequently disputed the official numbers, asserting a higher percentage of the country's population. According to the disputed 2011 census, ethnic affiliation was as follows: Albanians 2,312,356 (82.6% of the total), Greeks 24,243 (0.9%), Macedonians 5,512 (0.2%), Montenegrins 366 (0.01%), Aromanians 8,266 (0.30%), Romani 8,301 (0.3%), Balkan Egyptians 3,368 (0.1%), other ethnicities 2,644 (0.1%), no declared ethnicity 390,938 (14.0%), and not relevant 44,144 (1.6%).[302] On the quality of the specific data the Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities stated that "the results of the census should be viewed with the utmost caution and calls on the authorities not to rely exclusively on the data on nationality collected during the census in determining its policy on the protection of national minorities".[303]

There are 23,485 (1%) ethnic Greeks in Albania as shown on the latest 2023 Census.[1] The Greek government claimed there were an estimation of 300,000 ethnic Greeks in Albania.[304][305][306][307][308] The CIA World Factbook estimates the Greek minority to constitute 0.9%[309] of the population. The US State Department estimates that Greeks make up 1.17%, and other minorities 0.23%, of the population.[310] The latter questioned the validity of the 2011 census data about the Greek minority, as measurements had allegedly been affected by boycott.[311]

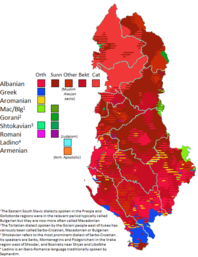

Language

This section needs to be updated. (May 2023) |

The official language of the country is Albanian which is spoken by the vast majority of the country's population.[312] Its standard spoken and written form is revised and merged from the two main dialects, Gheg and Tosk, though it is notably based more on the Tosk dialect. The Shkumbin river is the rough dividing line between the two dialects. Among minority languages, Greek is the second most-spoken language in the country, with 0.5 to 3% of the population speaking it as first language, mainly in the country's south where its speakers are concentrated.[313][314][315][316] Other languages spoken by ethnic minorities in Albania include Aromanian, Serbian, Macedonian, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Gorani, and Roma.[317] Macedonian is official in the Pustec Municipality in East Albania. According to the 2011 population census, 2,765,610 or 98.8% of the population declared Albanian as their mother tongue.[302] Because of large migration flows from Albania, over half of Albanians during their life learn a second language. The main foreign language known is English with 40.0%, followed by Italian with 27.8% and Greek with 22.9%. The English speakers were mostly young people, the knowledge of Italian is stable in every age group, while there is a decrease of the speakers of Greek in the youngest group.[318]

Among young people aged 25 or less, English, German and Turkish have seen rising interest after 2000. Italian and French have had a stable interest, while Greek has lost much of its previous interest. The trends are linked with cultural and economic factors.[319]

Young people have shown a growing interest in the German language in recent years.[citation needed] Some of them go to Germany for studying or various experiences. Albania and Germany have agreements for cooperating in helping young people of the two countries know both cultures better.[320] Due to a sharp rise in economic relations with Turkey, interest in learning Turkish, in particular among young people, has been growing on a yearly basis.[321]

Religion

Religion in Albania as of the 2023 census conducted by the Institute of Statistics (INSTAT)[1]

Albania is a secular and religiously diverse country with no official religion and thus, freedom of religion, belief and conscience are guaranteed under the country's constitution.[322] As of the 2023 Census, there were 1,101,718 (45.86%) Sunni Muslims, 201,530 (8.38%) Catholics, 173,645 (7.22%) Eastern Orthodox, 115,644 (4.81%) Bektashi Muslims, 9,658 (0.4%) Evangelicals, 3,670 (0.15%) of other religions, 332,155 (13.82%) believers without denomination, 85,311 (3.55%) Atheists and 378,782 (15.76%) did not provide an answer.[1] Albania is nevertheless ranked among the least religious countries in the world.[323] Religion constitute an important role in the lives of only 39% of the country's population.[324] In another report, 56% considered themselves religious, 30% considered themselves non-religious, while 9% defined themselves as convinced atheists. 80% believed in God.[325]