Radio telescope

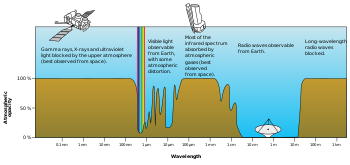

A radio telescope is a specialized antenna and radio receiver used to detect radio waves from astronomical radio sources in the sky.[1][2][3] Radio telescopes are the main observing instrument used in radio astronomy, which studies the radio frequency portion of the electromagnetic spectrum emitted by astronomical objects, just as optical telescopes are the main observing instrument used in traditional optical astronomy which studies the light wave portion of the spectrum coming from astronomical objects. Unlike optical telescopes, radio telescopes can be used in the daytime as well as at night.

Since astronomical radio sources such as planets, stars, nebulas and galaxies are very far away, the radio waves coming from them are extremely weak, so radio telescopes require very large antennas to collect enough radio energy to study them, and extremely sensitive receiving equipment. Radio telescopes are typically large parabolic ("dish") antennas similar to those employed in tracking and communicating with satellites and space probes. They may be used individually or linked together electronically in an array. Radio observatories are preferentially located far from major centers of population to avoid electromagnetic interference (EMI) from radio, television, radar, motor vehicles, and other man-made electronic devices.

Radio waves from space were first detected by engineer Karl Guthe Jansky in 1932 at Bell Telephone Laboratories in Holmdel, New Jersey using an antenna built to study radio receiver noise. The first purpose-built radio telescope was a 9-meter parabolic dish constructed by radio amateur Grote Reber in his back yard in Wheaton, Illinois in 1937. The sky survey he performed is often considered the beginning of the field of radio astronomy.

Early radio telescopes

[edit]The first radio antenna used to identify an astronomical radio source was built by Karl Guthe Jansky, an engineer with Bell Telephone Laboratories, in 1932. Jansky was assigned the task of identifying sources of static that might interfere with radiotelephone service. Jansky's antenna was an array of dipoles and reflectors designed to receive short wave radio signals at a frequency of 20.5 MHz (wavelength about 14.6 meters). It was mounted on a turntable that allowed it to rotate in any direction, earning it the name "Jansky's merry-go-round." It had a diameter of approximately 100 ft (30 m) and stood 20 ft (6 m) tall. By rotating the antenna, the direction of the received interfering radio source (static) could be pinpointed. A small shed to the side of the antenna housed an analog pen-and-paper recording system. After recording signals from all directions for several months, Jansky eventually categorized them into three types of static: nearby thunderstorms, distant thunderstorms, and a faint steady hiss above shot noise, of unknown origin. Jansky finally determined that the "faint hiss" repeated on a cycle of 23 hours and 56 minutes. This period is the length of an astronomical sidereal day, the time it takes any "fixed" object located on the celestial sphere to come back to the same location in the sky. Thus Jansky suspected that the hiss originated outside of the Solar System, and by comparing his observations with optical astronomical maps, Jansky concluded that the radiation was coming from the Milky Way Galaxy and was strongest in the direction of the center of the galaxy, in the constellation of Sagittarius.

An amateur radio operator, Grote Reber, was one of the pioneers of what became known as radio astronomy. He built the first parabolic "dish" radio telescope, 9 metres (30 ft) in diameter, in his back yard in Wheaton, Illinois in 1937. He repeated Jansky's pioneering work, identifying the Milky Way as the first off-world radio source, and he went on to conduct the first sky survey at very high radio frequencies, discovering other radio sources. The rapid development of radar during World War II created technology which was applied to radio astronomy after the war, and radio astronomy became a branch of astronomy, with universities and research institutes constructing large radio telescopes.[4]

Types

[edit]

The range of frequencies in the electromagnetic spectrum that makes up the radio spectrum is very large. As a consequence, the types of antennas that are used as radio telescopes vary widely in design, size, and configuration. At wavelengths of 30 meters to 3 meters (10–100 MHz), they are generally either directional antenna arrays similar to "TV antennas" or large stationary reflectors with movable focal points. Since the wavelengths being observed with these types of antennas are so long, the "reflector" surfaces can be constructed from coarse wire mesh such as chicken wire.[5] [6] At shorter wavelengths parabolic "dish" antennas predominate. The angular resolution of a dish antenna is determined by the ratio of the diameter of the dish to the wavelength of the radio waves being observed. This dictates the dish size a radio telescope needs for a useful resolution. Radio telescopes that operate at wavelengths of 3 meters to 30 cm (100 MHz to 1 GHz) are usually well over 100 meters in diameter. Telescopes working at wavelengths shorter than 30 cm (above 1 GHz) range in size from 3 to 90 meters in diameter.[citation needed]

Frequencies

[edit]The increasing use of radio frequencies for communication makes astronomical observations more and more difficult (see Open spectrum). Negotiations to defend the frequency allocation for parts of the spectrum most useful for observing the universe are coordinated in the Scientific Committee on Frequency Allocations for Radio Astronomy and Space Science.

Some of the more notable frequency bands used by radio telescopes include:

- Every frequency in the United States National Radio Quiet Zone

- Channel 37: 608 to 614 MHz

- The "Hydrogen line", also known as the "21 centimeter line": 1,420.40575177 MHz, used by many radio telescopes including The Big Ear in its discovery of the Wow! signal

- 1,406 MHz and 430 MHz [7]

- The Waterhole: 1,420 to 1,666 MHz

- The Arecibo Observatory had several receivers that together covered the whole 1–10 GHz range.

- The Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe mapped the cosmic microwave background radiation in 5 different frequency bands, centered on 23 GHz, 33 GHz, 41 GHz, 61 GHz, and 94 GHz.

Big dishes

[edit]

The world's largest filled-aperture (i.e. full dish) radio telescope is the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) completed in 2016 by China.[8] The 500-meter-diameter (1,600 ft) dish with an area as large as 30 football fields is built into a natural karst depression in the landscape in Guizhou province and cannot move; the feed antenna is in a cabin suspended above the dish on cables. The active dish is composed of 4,450 moveable panels controlled by a computer. By changing the shape of the dish and moving the feed cabin on its cables, the telescope can be steered to point to any region of the sky up to 40° from the zenith. Although the dish is 500 meters in diameter, only a 300-meter circular area on the dish is illuminated by the feed antenna at any given time, so the actual effective aperture is 300 meters. Construction was begun in 2007 and completed July 2016[9] and the telescope became operational September 25, 2016.[10]

The world's second largest filled-aperture telescope was the Arecibo radio telescope located in Arecibo, Puerto Rico, though it suffered catastrophic collapse on 1 December 2020. Arecibo was one of the world's few radio telescope also capable of active (i.e., transmitting) radar imaging of near-Earth objects (see: radar astronomy); most other telescopes employ passive detection, i.e., receiving only. Arecibo was another stationary dish telescope like FAST. Arecibo's 305 m (1,001 ft) dish was built into a natural depression in the landscape, the antenna was steerable within an angle of about 20° of the zenith by moving the suspended feed antenna, giving use of a 270-meter diameter portion of the dish for any individual observation.

The largest individual radio telescope of any kind is the RATAN-600 located near Nizhny Arkhyz, Russia, which consists of a 576-meter circle of rectangular radio reflectors, each of which can be pointed towards a central conical receiver.

The above stationary dishes are not fully "steerable"; they can only be aimed at points in an area of the sky near the zenith, and cannot receive from sources near the horizon. The largest fully steerable dish radio telescope is the 100 meter Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, United States, constructed in 2000. The largest fully steerable radio telescope in Europe is the Effelsberg 100-m Radio Telescope near Bonn, Germany, operated by the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, which also was the world's largest fully steerable telescope for 30 years until the Green Bank antenna was constructed.[11] The third-largest fully steerable radio telescope is the 76-meter Lovell Telescope at Jodrell Bank Observatory in Cheshire, England, completed in 1957. The fourth-largest fully steerable radio telescopes are six 70-meter dishes: three Russian RT-70, and three in the NASA Deep Space Network. The planned Qitai Radio Telescope, at a diameter of 110 m (360 ft), is expected to become the world's largest fully steerable single-dish radio telescope when completed in 2028.

A more typical radio telescope has a single antenna of about 25 meters diameter. Dozens of radio telescopes of about this size are operated in radio observatories all over the world.

Gallery of big dishes

[edit]-

The 500 meter Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST), under construction, China (2016)

-

The 100 meter Green Bank Telescope, Green Bank, West Virginia, US, the largest fully steerable radio telescope dish (2002)

-

The 100 meter Effelsberg, in Bad Münstereifel, Germany (1971)

-

The 76 meter Lovell, Jodrell Bank Observatory, England (1957)

-

The 70 meter DSS 14 "Mars" antenna at Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex, Mojave Desert, California, US (1958)

-

The 70 meter Yevpatoria RT-70, Crimea, first of three RT-70 in the former Soviet Union, (1978)

-

The 70 meter Galenki RT-70, Galenki, Russia, second of three RT-70 in the former Soviet Union, (1984)

Radiotelescopes in space

[edit]Since 1965, humans have launched three space-based radio telescopes. The first one, KRT-10, was attached to Salyut 6 orbital space station in 1979. In 1997, Japan sent the second, HALCA. The last one was sent by Russia in 2011 called Spektr-R.

Radio interferometry

[edit]

One of the most notable developments came in 1946 with the introduction of the technique called astronomical interferometry, which means combining the signals from multiple antennas so that they simulate a larger antenna, in order to achieve greater resolution. Astronomical radio interferometers usually consist either of arrays of parabolic dishes (e.g., the One-Mile Telescope), arrays of one-dimensional antennas (e.g., the Molonglo Observatory Synthesis Telescope) or two-dimensional arrays of omnidirectional dipoles (e.g., Tony Hewish's Pulsar Array). All of the telescopes in the array are widely separated and are usually connected using coaxial cable, waveguide, optical fiber, or other type of transmission line. Recent advances in the stability of electronic oscillators also now permit interferometry to be carried out by independent recording of the signals at the various antennas, and then later correlating the recordings at some central processing facility. This process is known as Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI). Interferometry does increase the total signal collected, but its primary purpose is to vastly increase the resolution through a process called aperture synthesis. This technique works by superposing (interfering) the signal waves from the different telescopes on the principle that waves that coincide with the same phase will add to each other while two waves that have opposite phases will cancel each other out. This creates a combined telescope that is equivalent in resolution (though not in sensitivity) to a single antenna whose diameter is equal to the spacing of the antennas furthest apart in the array.

A high-quality image requires a large number of different separations between telescopes. Projected separation between any two telescopes, as seen from the radio source, is called a baseline. For example, the Very Large Array (VLA) near Socorro, New Mexico has 27 telescopes with 351 independent baselines at once, which achieves a resolution of 0.2 arc seconds at 3 cm wavelengths.[12] Martin Ryle's group in Cambridge obtained a Nobel Prize for interferometry and aperture synthesis.[13] The Lloyd's mirror interferometer was also developed independently in 1946 by Joseph Pawsey's group at the University of Sydney.[14] In the early 1950s, the Cambridge Interferometer mapped the radio sky to produce the famous 2C and 3C surveys of radio sources. An example of a large physically connected radio telescope array is the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope, located in Pune, India. The largest array, the Low-Frequency Array (LOFAR), finished in 2012, is located in western Europe and consists of about 81,000 small antennas in 48 stations distributed over an area several hundreds of kilometers in diameter and operates between 1.25 and 30 m wavelengths. VLBI systems using post-observation processing have been constructed with antennas thousands of miles apart. Radio interferometers have also been used to obtain detailed images of the anisotropies and the polarization of the Cosmic Microwave Background, like the CBI interferometer in 2004.

The world's largest physically connected telescope, the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), is planned to start operations in 2025.

Astronomical observations

[edit]Many astronomical objects are not only observable in visible light but also emit radiation at radio wavelengths. Besides observing energetic objects such as pulsars and quasars, radio telescopes are able to "image" most astronomical objects such as galaxies, nebulae, and even radio emissions from planets.[15][16]

See also

[edit]- Aperture synthesis

- Astropulse – distributed computing to search data tapes for primordial black holes, pulsars, and ETI

- List of astronomical observatories

- List of radio telescopes

- List of telescope types

- Search for extraterrestrial intelligence

- Telescope

- Radar telescope

References

[edit]- ^ Marr, Jonathan M.; Snell, Ronald L.; Kurtz, Stanley E. (2015). Fundamentals of Radio Astronomy: Observational Methods. CRC Press. pp. 21–24. ISBN 978-1498770194.

- ^ Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2008. p. 1583. ISBN 978-1593394929.

- ^ Verschuur, Gerrit (2007). The Invisible Universe: The Story of Radio Astronomy (2 ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-0387683607.

- ^ Sullivan, W.T. (1984). The Early Years of Radio Astronomy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-25485-X

- ^ Ley, Willy; Menzel, Donald H.; Richardson, Robert S. (June 1965). "The Observatory on the Moon". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 132–150.

- ^ CSIRO. "The Dish turns 45". Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation. Archived from the original on August 24, 2008. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- ^ "Microstructure". Jb.man.ac.uk. 1996-02-05. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- ^ "China Exclusive: China starts building world's largest radio telescope". English.peopledaily.com.cn. 2008-12-26. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- ^ "China Finishes Building World's Largest Radio Telescope". Space.com. 2016-07-06. Retrieved 2016-07-06.

- ^ Wong, Gillian (25 September 2016), China Begins Operating World's Largest Radio Telescope, ABC News

- ^ Ridpath, Ian (2012). A Dictionary of Astronomy. OUP Oxford. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-19-960905-5.

- ^ "Microwave Probing of the Invisible". Archived from the original on August 31, 2007. Retrieved June 13, 2007.

- ^ Nature vol.158, p. 339, 1946

- ^ Nature vol.157, p.158, 1946

- ^ "What is Radio Astronomy?". Public Website.

- ^ "What are Radio Telescopes?".

Further reading

[edit]- Rohlfs, K., & Wilson, T. L. (2004). Tools of radio astronomy. Astronomy and astrophysics library. Berlin: Springer.

- Asimov, I. (1979). Isaac Asimov's Book of facts; Sky Watchers. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. pp. 390–399. ISBN 0-8038-9347-7