Invasion of the Spice Islands

| Invasion of the Spice Islands | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Napoleonic Wars | |||||||||

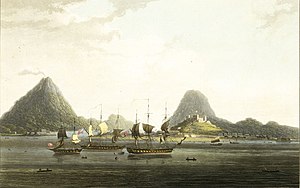

View of the Island of Banda Neira – captured by a force landed from a squadron under the Command of Captain Cole in the morning of 9 August 1810 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Christopher Cole Edward Tucker |

Herman Willem Daendels R. Coop à Groen | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

7 ships 1,000 soldiers and Marines | various forts and coastal defences | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| light | all islands, fortifications and military stores captured[1] | ||||||||

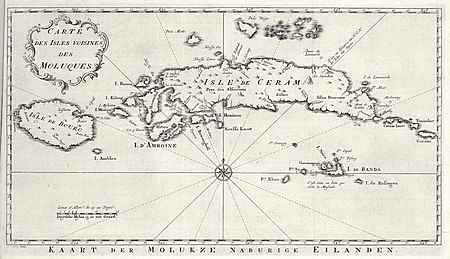

The invasion of the Spice Islands was a military invasion by British forces that took place between February and August 1810 on and around the Dutch owned Maluku Islands (or Moluccas) also known as the Spice Islands in the Dutch East Indies during the Napoleonic wars.

By 1810 the Kingdom of Holland was a vassal of Napoleonic France and Great Britain along with the East India Company sought to control the rich Dutch spice islands in the East Indies. Two British forces were allocated; one to the island of Ambon and Ternate, then another force would capture the more heavily defended islands of Banda Neira, following which any other island that was defended.

In a campaign that lasted seven months British forces took all of the islands in the region; Ambon was captured in February, Banda Neira in August and Ternate and all other islands in the region later that same month.[2]

The British held on to the islands until the end of the war. After the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814 the islands were handed back to the Dutch, but in the meantime the East India Company had uprooted a lot of the spice trees for transplantation throughout the British Empire.[3]

Background

[edit]

The Moluccas were known as the Spice Islands because of the nutmeg, mace and cloves that were exclusively found there. The presence of these sparked European colonial interest in the sixteenth century, starting with Portugal who virtually held a monopoly on the spice trade. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) arrived in the islands in 1599 and eventually ousted the Portuguese.

The English East India Company arrived soon after who in turn competed with the Dutch and had claimed the island of Ambon and the small island of Run. The competition soon came to a head with the Amboyna massacre in 1623 which influenced Anglo-Dutch relations for decades. After 1667 under the Treaty of Breda, both agreed to maintain the colonial status quo and relinquish their respective claims, which continued well in the eighteenth century.

After the financially disastrous Fourth Anglo-Dutch War the Dutch Republic became the Batavian Republic and allied with Revolutionary France. The VOC was then nationalised in 1796. During the war that followed Prince William V of Orange ordered the Dutch East India Company to hand over their colonies to the British to stop trade falling into French hands. The VOC was officially dissolved in 1799; the overseas possessions then became Dutch government colonies (the Moluccas became part of the Dutch East Indies). The islands were captured by Vice Admiral Peter Rainier – Ternate was later viciously contested by the Dutch.[4] These were subsequently returned as a result of the Treaty of Amiens seven years later. Peace however did not last long and thus began the Napoleonic Wars. By 1808, most of the Dutch colonies had been neutralised in a series of brief but successful campaigns; the Cape was invaded and captured by Sir Home Riggs Popham in January 1806 and the island of Java by Sir Edward Pellew in a campaign that ended in December 1807. The French and British were nevertheless each seeking to control the lucrative Indian Ocean trade routes. The British had started by invading the French Indian Ocean islands of Ile de France and Île Bonaparte in 1809.[5] The Dutch East Indies had to be taken by the British for a number of reasons; firstly it was necessary to subvert French power there before it entrenched itself too firmly to be dislodged easily by the British.[6] This was the primary concern of the East India Company who felt that their China trade would be threatened.[7]

Preparations

[edit]| Maluku Island spices |

|---|

In 1806 Herman Willem Daendels became Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies and sought to defend the region against the British. Using forced labour Daendels reinforced the garrisons, improved defences and built the Great Post Road in Java to counter a potential British threat.

In the middle of 1809 the Colonial Governor of India, 1st Earl of Minto wanted to set up two squadrons to conquer the Moluccas. This fell under Rear Admiral William O'Brien Drury who was resolved to seize the Dutch settlements.[8] The first was set up in February 1810 – Captain Edward Tucker commanded a small squadron comprising HMS Dover, the frigate HMS Cornwallis under Captain William Augustus Montagu and the sloop HMS Samarang. They carried two companies of troops numbering around 400 men of the Madras European Regiment and the Madras Artillery.[9] Their main objective were the islands of Amboyna and Ternate.[10]

The second force intended to capture the Banda Islands, the heart of the Spice trade – notably the strongly defended island of Banda Neira. The force comprised the 36-gun frigate Caroline, the former French frigate HMS Piedmontaise, the 18-gun sloop HMS Barracouta, and a 12-gun transport, the captured Dutch vessel Mandarin, which was serving as a tender to Caroline.[1] The frigates and sloop carried a hundred officers and men of the Madras European Regiment, as well as sailors and Royal Marines, and twenty men and two guns from the Madras Artillery.[11] The squadron was commanded by Captain Christopher Cole, with Captain Charles Foote on Piedmontaise and Captain Richard Kenah aboard Barracouta.[12] They departed from Madras and sailed via Singapore, where Captain Richard Spencer informed Cole that over 700 regular Dutch troops may be located in the Bandas.[13]

A number of East India Company agents were in tow partially to look at the idea of uprooting all of the spice trees namely nutmeg and clove which they had done on a small scale during the islands previous occupation in the 1790s. The primary consideration was the commercial advantage – the occupation of the Spice Islands meant not only a curtailment of the Dutch trade and power in the East Indies but also an equivalent gain to the company of the rich trade in spice.[14]

By 1810 the Kingdom of Holland was a vassal of Napoleonic France after being annexed under orders from Napoleon Bonaparte.

Invasion of the Moluccas

[edit]Amboyna

[edit]

The British force allocated to take Ambon left Madras on 9 October 1809. By the middle of the following February they arrived off the island the most considerable of the Dutch Spice islands and seat of government. On 6 February Dover captured the Dutch brig-of-war Rambang. Both Dover and Cornwallis anchored off the town of Ambon situated at the bottom of a small bay beneath a line of low hills.[9] These were defended by batteries along the beach as well as on some of the neighbouring heights and by Fort Victoria the main fort mounting a number of heavy guns. As the elevations on the left and in the rear of the town commanded its defences, the British intended to assault them.[10]

The British launched their attack on 16 February – the squadron at the same time occupied the attention of the Dutch by a vigorous cannonade. The troops aided by seamen and marines led by a Captain Court were landed on the right of the bay unnoticed by the Dutch, capturing two batteries that overlooked the port and Fort Victoria. During the night, Samarang landed forty men, who were joined by two field pieces from Dover. These joined in the bombardment of Fort Victoria as well as from the two captured batteries.[15]

British cannon fire from the ships and shore guns proved effective at showing considerable force – three ships were sunk in the harbour. A summons was then given to the Dutch Governor Colonel Filz for the surrender of the island, and after a few hours the articles of capitulation were agreed upon.[8] On 18 February the town capitulated; British casualties were extremely light, with only three dead, one of whom was a marine from Samarang. The entire island defended by 250 Europeans and around 1,000 Javanese and Madurese people laid down their arms.[15]

During the campaign the British captured several Dutch vessels. One was the Dutch brig Mandurese which had twelve guns. She was one of three vessels sunk in the inner harbour of Amboyna. However, the British raised her after the island surrendered. They took her into service as Mandarin.[16] From Amboyna, the squadron went on to capture the islands of Saparua, Haruku, Nusa Laut, Buru, and Manipa.[8]

After the attack on Amboyna, Spencer sailed Samarang to the island of Pulo Ay (or Pulo Ai), in the Banda Islands. There he conducted a successful and bloodless attack on Fort Revenge.[9] Spencer disguised Samarang to look like a Dutch merchant vessel, which fooled the fort's commander, enabling Spencer to take the fort by surprise. The Dutch commander committed suicide by taking poison after he realised that he had surrendered to what was a relatively weak British force.[17]

Next, Samarang captured the Dutch brig Recruiter on 28 March, when she arrived off the island of Pulau Ai. She was armed with twelve guns and had a crew of fifty men under the command of Captain Hegenheard. She had on board 10,000 dollars, the payroll of which were for the Dutch garrison at Banda Neira as well as provisions, a doctor, nurse, and twenty infants, on their way to conduct a vaccination campaign.[17] Samarang shared the prize money by agreement with Dover and Cornwallis. Between 29 April and 18 May, Dover, Cornwallis, and Samarang captured the Dutch ships Engelina and Koukiko. Both Pulau Ai and Run were captured without a fight.[18]

After sending all the Dutch officers and troops from Amboyna to Java, Captain Tucker sailed for the Dutch port of Gorontello, in the Bay of Tommine, on the north-east part of the island of Celebes in June 1810. Although the Dutch flag was flying over Fort Nassau, the settlement was governed by a Sultan and his two sons on behalf of the Dutch. He persuaded the Sultan to allow the British to replace the Dutch – which he agreed to.[8]

Finally on 26 June Dover captured the island of Manado, where Fort Amsterdam was protected by two heavy batteries. The fort surrendered without opposition when Captain Tucker pointed out to the Dutch Governor that an English frigate, with guns ready to fire and volunteers waiting in her boats, was waiting to storm the Dutch position. Manado had a garrison of 113, including officers, and the fort and the batteries mounted fifty guns.[Note 1]

Banda Neira

[edit]

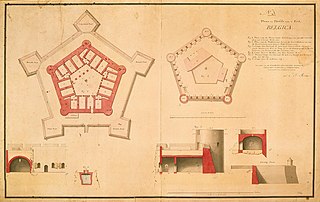

The British force destined for the Banda Islands appeared at Banda Neira on 9 August. The main defence on the islands was Fort Belgica which is a fairly significant position built in the stereotypical Vauban pentagon and surrounded by a ditch.[20] The older Fort Nassau lay further down to Belgica. The defences had been strengthened since the British had left the islands. In addition there were ten batteries (exclusive of the two forts) and as Spencer had predicted, there were 700 regular Dutch troops and 800 native militia.[9]

The operational concept was to approach Banda Neira after dark on 8 August and disembark the landing force of about 400 sailors, marines, and European infantry in small boats. These boats would run into the harbour before dawn and take Fort Belgica and other strongpoints by surprise.[21]

In the event, not much went according to plan. They were taken under fire from a battery during the night from the small island of Rosensgan as the Dutch were on alert, then the weather worsened dispersing the fleet of small boats. About 100 yards from the shore and directly opposite a Dutch battery consisting of ten 18-pounders the boats grounded on a coral reef. The men leapt into the water, then after an hour and a half before daylight the force were able to land in a sandy cove.[1] When Captain Cole reached the assembly area for the attack there were less than 200 seaman, marines and soldiers remaining. He made the decision to press ahead with the attack – Commander Richard Kenah of Barracouta attacked the Dutch battery in front of them from the rear. Using boarding pikes they killed one sentry and captured the remainder of the garrison, some sixty men, without firing a shot.[21]

Leaving a small guard in the battery – twenty minutes later they attempted to storm Fort Belgica. As dawn was breaking they were helped by a native guide to the outer ramparts of the fort. Despite the British being spotted and the alarm called, the heavy rain worked to the advantage of the attackers.[8] The defenders visibility was reduced and their firearms rendered useless. Having erected scaling ladders the attackers stormed over the outer walls and despite coming under desultory musket fire this part of the fort was stormed and taken. The inner walls were then attempted but the ladders were too short. However, the main gate had been opened to admit the commandant who lived outside. The British took the opportunity, made a rush, and by 5:30am the fort was in their possession. The Dutch side the fort commandant and ten men were killed, two officers and thirty men were taken prisoner, along with fifty two cannon. The British loss was trifling with only a few men wounded.[10]

Captain Cole sent Commander Kenah to demand the surrender of the Dutch governor.[21] As negotiations were taking place the Caroline, Piedmontaise, and Barracouda attempted to enter the harbour but were fired on by Dutch batteries. The British used the guns of Fort Belgica to return fire and threatened to destroy the nearby town if the governor did not surrender but he complied.[9]

-

Map and elevation of Fort Belgica on Banda Neira

-

Fort Belgica today

Ternate

[edit]The final part of the campaign involved the capture of the island of Ternate, the last remaining Dutch possession of any consequence in the Moluccas; after capturing Manado, Tucker and 174 men from HMS Dover arrived there on 25 August. The plan was to capture Fort Kalamata a small fortress which lies near the main town which was made up Fort Oranje; a bigger fort – this contained 92 heavy calibre guns and a garrison of 500 men of which 150 were Dutch. Many of the natives soldiers however had been in near mutiny over their pay.[22]

After having found an amphibious landing difficult at night Tucker and his men resorted in daylight and succeeded at Sasa, a village screened by a point of land from the fort by 7am on 28 August. They managed to ascend a hill, occupied it to place a field gun to command the position. The area on top was covered in thick forest and so Tucker attempted a night march. They were met by a roadblock, so a detour along a stream led to a sharp firefight against a strong Dutch detachment.[10] After driving the Dutch away with a bayonet charge, they came across a beach which was only within a hundred yards of Fort Kalamata. The Dutch opened fire, but even so the attackers decided to make an assault. After crossing a ditch, the British stormed the fort using scaling ladders on the flank of the bastion, and carried it after some sharp fighting.[23] Owing to the darkness and rapidity of the advance the casualties were moderate with three killed and fourteen wounded.[9]

Tucker attempted to demand the Dutch governor Colonel Jon van Mithman to surrender but in response guns were fired at the British ships from Fort Kota Baro a small fort which lay in between Kalamata and Oranje. Dover having placed her herself in front of it then used hers guns to silence the battery, following which a small detachment took possession of after a surprise attack. Dover then faced off against Fort Oranje pounding it with considerable effect. The Dutch fought back for a few hours, but after experiencing severe damage to the fort and rising losses it was then assaulted by a surprise attack from the rear by a Royal Marine detachment from Kalamata led by Lieutenant Cursham. The British then turned both fort guns on the town itself, and with Dover then pounded the town.[9] By 5am the Dutch had had enough and the town finally surrendered.[22]

A day after the town's surrender Mithman then surrendered the island to the British who promptly took possession.[10] By August 31 the campaign in the Moluccas had ended.[24]

Aftermath

[edit]

After the Dutch surrender, Captain Charles Foote (of Piedmontaise) was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of the Banda Islands. This action was a prelude to Britain's invasion of Java in 1811 which Cole also took a leading role in planning and executing. This was successfully completed under Rear-Admiral Robert Stopford.[13] For his services, Cole was knighted in May 1812, awarded a specially minted medal, and given an honorary doctorate by the University of Oxford.[12]

Before the Dutch regained control of the islands, the East India Company used their occupation of the Spice Islands to gather spice seedlings. Thus began a transplantation on an almost industrial scale – most were sent to Bencoolen and Penang, as well as Ceylon and other British colonies.[25] In the previous occupation in the 1790s the EIC had established spice gardens in Penang; by 1805 these contained 5,100 nutmeg trees and 15,000 clove trees. After the occupation in 1815 that number had jumped to 13,000 nutmeg trees and as many as 20,000 clove trees.[10] From these locations the trees were then transplanted to other British colonies elsewhere, notably Grenada and later Zanzibar. As a result, this competition largely destroyed the value of the Banda Islands to the Dutch.[3]

The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814 restored the islands as well as Java to the Dutch. The islands then remained part of the Dutch East Indies, a colony of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, until Indonesia's independence in 1945.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Notes

- Citations

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Woodman pp. 104–06

- ^ "Sir Christopher Cole, K.C.B.". The Annual biography and obituary. Vol. 21. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. 1837. pp. 114–123. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Milne, Peter (16 January 2011). "Banda, the nutmeg treasure islands". Jakarta Post. Jakarta. pp. 10–11. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

But the economic importance of the Bandas was only fleeting. With the Napoleonic wars raging across Europe, the British returned to the Bandas in the early 19th century, temporarily taking over control from the Dutch. The English uprooted hundreds of valuable nutmeg seedlings and transport them to their own colonies in Ceylon and Singapore, breaking forever the Dutch monopoly and consigning the Bandas to economic decline and irrelevance.

- ^ Wolter, John Amadeus (1999). he Napoleonic War in the Dutch East Indies: An Essay and Cartobibliography of the Minto Collection Issue 2 of Occasional paper series // Philip Lee Phillips Society Issue 2. Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress. p. 5.

- ^ Gardiner 2001, p. 92

- ^ Das p. 194

- ^ Moore & van Nierop p. 121

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e James pp 191–94

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Paget, William Henry (1907). Frontier and overseas expeditions from India. Government Monotype Press. pp. 319–24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Burnett pp 201–03

- ^ "102nd Regiment of Foot (Royal Madras Fusiliers): Locations". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 22 February 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tracy p 86

- ^ Jump up to: a b Adkins, Roy; Adkins, Lesley (2008). The War for All the Oceans: From Nelson at the Nile to Napoleon at Waterloo. Penguin. pp. 344–355. ISBN 978-0-14-311392-8. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ Das pp 191–92

- ^ Jump up to: a b Clarke & McArthur 337-41

- ^ Winfield (2008), p. 350.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chessell (2005), pp. 51–4.

- ^ "No. 17081". The London Gazette. 18 November 1815. p. 2308.

- ^ "No. 17100". The London Gazette. 16 January 1816. p. 93.

- ^ van de Wall, V.I (1928). De Nederlandsche Oudheden in de Molukken [Dutch Antiquities in the Moluccans] (in Dutch). 's-Gravenhage: Martinus Nijhoff.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wilson, Horace Hayman (1845). The History of British India: From 1805–1835 Volume 1 of The History of British India from 1805 to 1835. J. Madden & Company. pp. 341–48.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hanna, Willard Anderson; Alwi, Des (1990). Turbulent Times Past in Ternate and Tidore. Yayasan Warisan dan Budaya Banda Naira. p. 233.

- ^ Thomas p. 223

- ^ Wilson, William John (1883). History of the Madras Army, Volume 3. E. Keys at the Government Press. pp. 316–18.

- ^ Milton p. 380

Bibliography

[edit]- Burnett, Ian (2013). East Indies. Rosenberg Publishing. ISBN 978-1-922013-87-3.

- Chessell, Gwen S. J (2005). Richard Spencer: Napoleonic war naval hero and Australian pioneer. UWA Publishing. ISBN 978-1-920694-40-1.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John, eds. (2010). The Naval Chronicle: Volume 24, July-December 1810: Containing a General and Biographical History of the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom with a Variety of Original Papers on Nautical Subjects, Volume 24 Cambridge Library Collection – Naval Chronicle. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-01863-0.

- Das, Aditya, ed. (2016). Defending British India Against Napoleon: The Foreign Policy of Governor-General Lord Minto, 1807–13 Volume 13 of Worlds of the East India Company. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-78327-129-0.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (2001) [1998]. The Victory of Seapower. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-359-1.

- James, William (2011). The Naval History of Great Britain: A New Edition, with Additions and Notes, and an Account of the Burmese War and the Battle of Navarino. Vol. 5. Cambridge University Press London. ISBN 978-1-108-02169-2.

- Milton, Giles (2012). Nathaniel's Nutmeg: How One Man's Courage Changed the Course of History. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1-4447-1771-6.

- Moore, Bob; van Nierop, Henk (2017). Colonial Empires Compared: Britain and the Netherlands, 1750–1850. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-95050-3.

- Thomas, David (1998). Battles and Honours of the Royal Navy. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-0-85052-623-3.

- Tracy, Nicholas (1998). Who's Who in Nelson's Navy; 200 Naval Heroes. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-244-5.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-86176-246-7.

- Woodman, Richard (2005). The Victory of Seapower: Winning the Napoleonic War 1806–1814. Mercury Books. ISBN 978-1-86176-038-8.