University of Oxford Botanic Garden

| University of Oxford Botanic Garden & Harcourt Arboretum | |

|---|---|

View outside the Walled Garden with Magdalen Tower in the background | |

| |

| Type | Botanic Garden |

| Location | High Street, Oxford, England |

| Coordinates | 51°45′02″N 1°14′54″W / 51.75056°N 1.24833°W |

| Area | 1.8 hectares (18,000 m2) |

| Created | 1621[1] |

| Operated by | University of Oxford |

| Visitors | 211,573 (2019)[2] |

| Status | Open all year |

| Website | https://www.obga.ox.ac.uk |

The University of Oxford Botanic Garden is the oldest botanic garden in Great Britain and one of the oldest scientific gardens in the world. The garden was founded in 1621 as a physic garden growing plants for medicinal research. Today it contains over 5,000 different plant species on 1.8 ha (4+1⁄2 acres). It is one of the most diverse yet compact collections of plants in the world and includes representatives from over 90% of the higher plant families.[citation needed]

Professor Simon Hiscock became Director of Oxford Botanic Garden in 2015.[3][4]

History[edit]

Foundation[edit]

In 1621, Henry Danvers, 1st Earl of Danby, contributed £5,000 (in excess of £5,000,000 in 2018)[5] to set up a physic garden for "the glorification of the works of God and for the furtherance of learning". He chose a site on the banks of the River Cherwell at the northeast corner of Christ Church Meadow, belonging to Magdalen College. Part of the land had been a Jewish cemetery until the Jews were expelled from Oxford (and the rest of England) in 1290. Four thousand cartloads of "mucke and dunge" were needed to raise the land above the flood-plain of the River Cherwell.[6]

Catalogue[edit]

The first head gardener was the Botanist Jacob Bobart who in 1648 published a catalogue of sixteen hundred plants under his care ('Catalogus plantarum horti medici Oxoniensis, scil. Latino-Anglicus et Anglico-Latinus') with their Latin and English names; this was revised in 1658 in conjunction with his son, Jacob Bobart the Younger, Dr Philip Stephens, and William Brown. Humphry Sibthorp began the catalogue of the plants of the garden, Catalogus Plantarum Horti Botanici Oxoniensis. His youngest son was the botanist John Sibthorp (1758–1796), who continued the Catalogus Plantarum.[citation needed]

Layout[edit]

The Garden comprises three sections:

- the Walled Garden, surrounded by the original seventeenth-century stonework and home to the Garden's oldest tree; an English yew, Taxus baccata

- the Glasshouses, which allow the cultivation of plants needing protection from the extremes of British weather

- the Lower garden

- the area between the Walled Garden and the River Cherwell

A satellite site, the Harcourt Arboretum, is located six miles (9.7 km) south of Oxford.[citation needed]

The Danby Gate[edit]

The Danby Gate at the front entrance to the Botanic Garden is one of three entrances designed[8] by Nicholas Stone between 1632 and 1633. It is one of the earliest structures in Oxford to use classical, indeed early Baroque, style, preceding his new entrance porch for the University Church of St Mary the Virgin of 1637, and contemporary with the Canterbury Quad at St John's College by others. In this highly ornate arch, Stone ignored the new simple classical Palladian style then in fashion, which had been introduced to England from Italy by Inigo Jones, and drew his inspiration from an illustration in Serlio's book of archways.[9]

The gateway consists of three bays, each with a pediment. The largest and central bay, containing the segmented arch is recessed, causing its larger pediment to be partially hidden by the flanking smaller pediments of the projecting lateral bays.[citation needed]

The stone work is heavily decorated being bands of alternating vermiculated rustication and plain dressed stone. The pediments of the lateral bays are seemingly supported by circular columns which frame niches containing statues of Charles I and Charles II in classical pose. The tympanum of the central pediment contains a segmented niche containing a bust of the Earl of Danby. It is a Grade I listed structure (ref. 1485/423). The gate was shot at during the English Civil War. It previously held a statue of Charles I and one other (probably the Queen) as Charles II was only three years old when the gateway was built. The restoration dates from around 1653 and portrays both the late Charles I and the then current king, Charles II. It was sculpted by William Bird of Oxford.[10]

Walled garden[edit]

- Botanical Family beds

The core collection of hardy plants are grouped in long, narrow, oblong beds by botanical family and ordered according to the classification system devised by nineteenth century botanists, Bentham and Hooker. The families represented in the Walled Garden include: Acanthaceae, Amaranthaceae, Amaryllidaceae, Apocynaceae, Araceae, Aristolochiaceae, Berberidaceae, Boraginaceae, Campanulaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Chenopodiaceae, Cistaceae, Commelinaceae, Compositae, Convolvulaceae, Crassulaceae, Cruciferae, Cyperaceae, Dioscoreaceae, Dipsacaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Gentianaceae, Geraniaceae, Gramineae, Hypericaceae, Iridaceae, Juncaceae, Labiatae, Leguminosae, Liliaceae, Linaceae, Loasaceae, Lythraceae, Malvaceae, Onagraceae, Paeoniaceae, Papaveraceae, Phytolaccaceae, Plantaginaceae, Plumbaginaceae, Polemoniaceae, Polygonaceae, Portulacaceae, Primulaceae, Ranunculaceae, Rosaceae, Rubiaceae, Rutaceae, Saxifragaceae, Solanaceae, Umbelliferae, Urticaceae, Verbenaceae, Violaceae.

In 1983, The National Council for the Conservation of Plants and Gardens (NCCPG) chose Oxford Botanic Garden to cultivate the national collection of euphorbia. One of the rarest plants in the collection is Euphorbia stygiana, with only ten plants left existing in the wild. The Garden is propagating the species as quickly as possible to reduce the possibility of it becoming extinct.[citation needed]

- Medicinal beds

The South West corner of the Botanic Garden is home to a modern medicinal plant collection. Here you will find 8 beds, each growing plants with a connection to medicine used to treat a particular type of disease or illness. There are beds for

- Cardiology (heart complaints)

- Oncology (cancer and cell-proliferation)

- Infectious Diseases (viral and parasitic)

- Gastreoenterology (alimentary tract and metabolism)

- Dermatology (skin complaints)

- Haematology (blood typing and disorders)

- Neurology (nervous system and anaesthesia)

- Pulmonology (lungs and airways)

The plants growing in these beds contain many different natural products and fall into at least one of the following three categories:

- Directly suitable for use as a drug

- Synthetic modification provides a clinically suitable drug

- Starting point for a drug discovery programme

- Bearded irises

One bed in the northwest corner of the garden contains a display of bearded irises each May. Examples include Iris 'Eileen' and Iris 'Golden Encore'. Some of the varieties grown in the Garden are not grown anywhere else.[citation needed]

- Wall borders

The borders along the foot of the wall contain collections that thrive in the microclimate, many of these plant collections are grouped by their geographical origin. The Mediterranean collection at the north border includes Euphorbia myrsinites. The South American collection at the north border includes Feijoa sellowiana (syn. Acca sellowiana). The South African collection at the northeast border includes Kniphofia caulescens.[citation needed]

Other wall borders contain plants from Biodiversity hotspots including Japan and New Zealand. Such areas hold high numbers of Endemic plant species, yet face substantial threat to their natural vegetation. Over 50% of the world's plant species are contained within these hotspots which collectively cover only 2.3% of the Earth's land surface.[citation needed]

Glasshouses[edit]

- Conservatory

The house is an aluminium replica of the original 1893 wooden house and grows seasonal flowers such as primulas, abutilons, fuchsias, and achimenes. Various exhibitions which change throughout the year are displayed in the centre area.

- Alpine House

Plants which cannot grow to their full potential outside are displayed in this house. The displays are changed regularly so that there is always something in flower.[citation needed]

- Fernery

A collection of ferns from around the world are housed here including Platycerium bifurcatum (stag's horn fern), Lygodium japonicum (a climbing fern), and Trichomanes speciosum (a filmy fern native to western Britain).

- Tropical Lily House

The tank in the lily house built in 1851 by Professor Charles Daubeny, Keeper of the Garden at the time, is the oldest existing part of the glasshouses. Tropical water lilies grow in boxes in the tank, including the hybrid Nymphaea × daubenyana named in honour of Professor Daubeny in 1874. Also growing in the house are economic plants including bananas, sugar cane, and rice, and the papyrus reed, Cyperus papyrus, a native of river banks in the Middle East. Flowering high in the glasshouse is the yellow-flowered Allamanda cathartica.[citation needed]

- Insectivorous House

This house grows a collection of Carnivorous plants. Carnivory has evolved several times in plants and this collection displays many of the mechanisms required to trap insect prey. Some traps are passive, such as the sticky flypaper of the genus Pinguicula whereas others like the Venus flytrap, Dionaea muscipula, actually move and are triggered by the unlucky insect walking across the surface.[citation needed]

- Palm House

The largest glasshouse in the Garden, this house grows palms and a large number of economic plants including citrus fruits, pepper, sweet potato, pawpaw, olive, coffee, ginger, coconut, cocoa, cotton, and oil palm. There is a collection of cycads which look like palms but are unrelated. Several important teaching collections present include the Acanthaceae including the shrimp plant Justicia brandegeana, the Gesneriaceae, and a large number of Begonia species.[citation needed]

- Arid House

Plants in this house come from arid areas of the world and demonstrate ways in which plant forms economize the use of water. Many different species of Cacti and Succulent plants are found here demonstrating all of their various tactics to reduce water loss to their hostile environments.[citation needed]

Outside the walled garden[edit]

- Rock Garden

- Bog Garden

- Herbaceous Border

First laid out in 1946, this planting is a classic example of the traditional English herbaceous border. Unlike other areas of the Garden, this border relies entirely on herbaceous perennials. These die back to a rootstock each winter before bursting back into life again in spring and flowering through the summer. The planting is designed to provide interest from April to October. The display begins with tulips in a range of colours, followed by early, mid-season and late flowering perennials. The plants are arranged in layers, with the smaller plants positioned at the front of the border and the taller plants toward the back. Occasionally we allow a few of the larger plants to make their way to the front to break up the formality.[citation needed]

- Autumn Border

- Glasshouse Borders

- Merton Borders

Designed in collaboration with Professor James Hitchmough from the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Sheffield

At 955m2 these borders form the largest single cultivated area in the Botanic Garden. They are an example of sustainable horticultural development, with minimal impact on the environment in the long term.[citation needed]

The plants have been selected for their ability to withstand drought conditions and originate from seasonally dry grassland communities in three regions of the world:

- The Central to Southern Great Plains (USA) through to the Colorado Plateau and into California

- East South Africa at latitudes above 1000m

- Southern Europe to Turkey and across Asia to Siberia

In literature[edit]

The Garden was the site of frequent visits in the 1860s by the Oxford mathematics professor Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) and the Liddell children, Alice and her sisters. Like many of the places and people of Oxford, it was a source of inspiration for Carroll's stories in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. The Garden's waterlily house can be seen in the background of Sir John Tenniel's illustration of "The Queen's Croquet-Ground".[citation needed]

Another Oxford professor and author, J. R. R. Tolkien, often spent his time at the garden reposing under his favourite tree, Pinus nigra. The enormous Austrian pine was much like the Ents of his The Lord of the Rings story, the walking, talking tree-people of Middle-earth.[11] However, the tree was removed in 2014 after two limbs fell, posing a security risk for the visitors.[12][13]

In the Evelyn Waugh novel Brideshead Revisited, Lord Sebastian Flyte takes Charles Ryder "to see the ivy" soon after they first meet. As he says, "Oh, Charles, what a lot you have to learn! There's a beautiful arch there and more different kinds of ivy than I knew existed. I don't know where I should be without the Botanical gardens" (Chapter One).[citation needed]

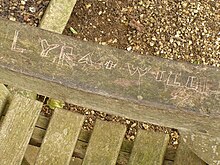

In Philip Pullman's trilogy of novels His Dark Materials, a bench in the back of the garden is one of the locations that stand parallel in the different worlds that the two protagonists, Lyra Belacqua and Will Parry, inhabit.[14] In the last chapter of the trilogy, both promise to sit on the bench for an hour at noon on Midsummer's day every year so that perhaps they may feel each other's presence next to one another in their own worlds. Now a place of pilgrimage for Pullman's fans, the bench is recognizable due to graffiti such as "Lyra + Will" or "L + W" left by its visitors[15] and, since 2019, the sculpture by Julian Warren installed behind it.[16]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Oxford Botanic Garden & Arboretum – Celebrating 400 years". University of Oxford Botanic Garden. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- ^ "ALVA - Association of Leading Visitor Attractions". www.alva.org.uk. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "Professor Simon Hiscock". www.obga.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "Simon Hiscock". worc.ox..ac.uk. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Lawrence H. Officer, "Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1264 to 2005". MeasuringWorth.com, 2006, accessed 11 December 2006.

- ^ Oxfordhistory.org.uk.

- ^ "The Danby Gate (Oxford, 1632-3): a portal between two worlds | cabinet". www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ "probably designed", according to Colvin 1995.

- ^ Pevsner, p. 267. Pevsner is almost certainly referring to Tutte l'opere d'architettura, Volume 6. p. 17. "Libro estraordinario" published in 1584.

- ^ Cole, J. C. (1949). "William Byrd, Stonecutter and Mason" (PDF). Oxoniensia. 163: 63–74.

- ^ "Oxford Botanic Garden". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Botanic Garden bids farewell to iconic black pine | University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "A giant falls: Tolkien's tree | Oxford Today". www.oxfordtoday.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Leonard, Bill, The Oxford of Inspector Morse Location Guides, Oxford (2004) p.198. ISBN 0-9547671-1-X.

- ^ "New Philip Pullman-themed Oxford tour lets you explore the city through Lyra's eyes". The Independent. 19 October 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "GRAY MATTER: Philip Pullman's daemons descend on Oxford Botanic Garden". The Oxford Times. 6 June 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

References[edit]

- Colvin, Howard, A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects, 1600–1840 3rd ed. (Yale University Press) 1995, s.v. "Stone, Nicholas"

- Jennifer Sherwood, Nikolaus Pevsner (1974). The Buildings of England, Oxfordshire. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09639-9.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Virtual tour Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- The Friends of Oxford Botanic Garden

- Oxford Botanic Garden — a Gardens Guide review Archived 6 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- 1621 establishments in England

- Buildings and structures completed in 1621

- Botanical gardens in England

- Gardens in Oxfordshire

- Culture of the University of Oxford

- Departments of the University of Oxford

- University of Oxford sites

- History of the University of Oxford

- Parks and open spaces in Oxford

- Tourist attractions in Oxford

- Grade I listed buildings in Oxford

- Lewis Carroll

- Alice Liddell

- J. R. R. Tolkien