History of the Jews in Bessarabia

The history of the Jews in Bessarabia, a historical region in Eastern Europe, dates back hundreds of years.

Early history

[edit]

Jews are mentioned from very early on in the Principality of Moldavia, but they did not represent a significant number. Their main activity in Moldavia was commerce, but they could not compete with Greeks and Armenians, who had knowledge of Levantine commerce and relationships.[citation needed]

Several times, when Jewish merchants created monopolies in some places in north Moldavia, Moldavian rulers sent them back to Galicia and Podolia. One such example was during the reign of Petru Şchiopul (1583–1591), who favored the English merchants led by William Harborne.[1]

In the 18th century, more Jews started to settle in Moldavia. Some of them were in charge of the Dniester crossings, replacing Moldavians and Greeks, until the captain of Soroca demanded their expulsion.

Others traded with spirits (horilka), first brought in from Ukraine, afterward building local velniţas (pre-industrial distilleries) on boyar manors. The number of Jews increased significantly during the Russo-Turkish War (1806–1812), when the Podolia-Moldavia border was open.[1]

When this war ended, in 1812, Bessarabia (eastern half of the Principality of Moldavia) was annexed by the Russian Empire.

Governorate of Bessarabia (1812–1917)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

Status

[edit]The 1818 Statutory Law (Aşezământul) of the Governorate of Bessarabia mentions Jews as a separate state (social class), which was further divided into merchants, tradesmen, and land-workers. Unlike the other states, Jews were not allowed to own agricultural land, with the exception of "empty lots only from the property of the state, for cultivation and for building factories". Jews were allowed to keep and control the sale of spirits on government and private manors, to hold "mills, velniţas, breweries, and similar holdings", but were explicitly disallowed to "rule over Christians". During the 1817 census, there were 3,826 Jewish families in Bessarabia (estimated at 19,000 people, or 4.2% of the total population).[1]

Rural colonies

[edit]Over the next generations, the Jewish population of Bessarabia grew significantly. Unlike most of the rest of the Russian Empire, in Bessarabia, Jews were allowed to settle in fairs and cities. Tsar Nicholas I issued an ukaz (decree) that allowed Jews to settle in Bessarabia "in a higher number", giving settled Jews two years free of taxation. At the same time, Jews from Podolia and Kherson Governorates were given five years free of taxation if they crossed the Dniester and settle in Bessarabia.[2]

As a result, the merchant activity was not enough to sustain all Jews, which led the Tsarist authorities to create 17 Jewish agricultural colonies:

In Soroca County

[edit]- Dumbrăveni (now part of Vădeni commune)

- Brăciova (Bricevo, now Briceva, part of Târnova commune in Dondușeni district)

- Mărculești (Starăuca/Starovka, for some period)

- Vârtojani (Vertiujeni, Șteap for some period)

- Lublin (later Nemirovka, now Nimereuca)

- Căprești

- Zguriţa

- Maramonovca

- Constantinovca

In Orhei County

[edit]- Șibca (now Șipca)

- Nicolaevca-Blagodaţi (now Neculăieuca)

- Teleneștii Noi

In Chișinău County

[edit]- Grătiești and Hulboaca under joint administration (both now part of Grătești commune within Rîșcani sector of Chișinău)

In Bălți County

[edit]- Alexăndreni (now part of Alexăndreni Commune in Sîngerei District)

- Valea lui Vlad (now part of Dumbrăvița Commune in Sîngerei District)

In Hotin County

[edit]- Lomacinţa (now in Dnistrovskyi Raion, Chernivtsi Oblast of Ukraine)

In Tighina County

[edit]- Romanăuţi (Romanovca) (now within city limits of Basarabeasca)

10,589 Jews were settled in these villages, forming 1,082 households. This plan was borrowed from the ideas of Emperor Joseph II of Austria in regard to Bukovina Jews, but it became impractical as there Jews preferred to leave Bukovina than to settle in villages. The impression that Jews would not stay in the rural areas was proved wrong by the Russian Tzar, as his colonization at first seemed a success. However, after several years, Jews in these rural colonies preferred merchant activities with cattle, leather, wool, tobacco, while their agricultural land was mostly rented out to Christian peasants. After more years, many of these Jews moved to fairs and sold their land to Moldavians. During the 1856 census, there were 78,751 Jews in Bessarabia (about 8% of the total population of 990,000).[2]

Late 19th and early 20th centuries

[edit]

- 1889: There were 180,918 Jews of a total population of 1,628,867 in Bessarabia, or 11.11%

- 1897: The Jewish population had grown to 225,637 of a total of 1,936,392, or 11.65%

- 1903: Chișinău (then known as Kishinev), in Russian Bessarabia had a Jewish population of 50,000, or 46%, out of a total of approximately 110,000. Jewish life flourished with 16 Jewish schools and over 2,000 pupils in Chişinău alone.

Kishinev pogrom

[edit]

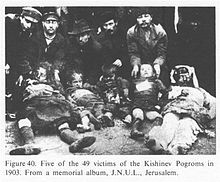

16 February 1903: Kishinev pogrom.

In 1903, a Christian Ukrainian boy, Mikhail Ribalenko, was found murdered in the town of Dubăsari, about 40 kilometres (25 mi) northeast of Chișinău; the town is on the left bank of the river Dniester and was not a part of Bessarabia. Although it was clear that the boy had been killed by a relative (who was later found), the government called it a ritual murder plot by the Jews. The mobs were incited by Pavel Krushevan, the editor of the Russian language anti-Semitic newspaper Bessarabian and the vice-governor Ustrugov.[citation needed] The newspaper regularly accused the Jewish community of numerous crimes, and on multiple occasions published headlines such as "Death to the Jews!" and "Crusade Against the Hated Race!"[3] They used the age-old calumny against the Jews (that the boy had been killed to use his blood in preparation of matzo).

Viacheslav Plehve, the Minister of Interior, supposedly gave orders not to stop the rioters. However, the pogrom lasted for three days, without the intervention of the police. Forty seven (some say 49) Jews were killed, 92 severely wounded, 500 slightly wounded and over 700 houses destroyed. Despite a world outcry, only two men were sentenced to seven and five years and 22 were sentenced for one or two years. This pogrom is considered the first state-inspired action against Jews in the 20th century[citation needed] and was instrumental in convincing tens of thousands of Russian Jews to leave to the West and to Palestine.[citation needed] Many of the younger Jews, including Mendel Portugali, made an effort to defend the community.

1917–1940

[edit]Moldavian Democratic Republic

[edit]In the Sfatul Țării, Bessarabian Jews were represented by:

- Isac Gherman, 60 years old, lawyer from Chişinău

- Eugen Kenigschatz, 58, lawyer, Chişinău

- Samuel Lichtmann, 60, civil servant

- Moise Slutski, 62, physician, Chişinău

- Gutman Landau, 40, civil servant

- Mendel Steinberg

The former four abstained from vote for the Union of Bessarabia with Romania on April 9 [O.S. March 27] 1918, while the latter two were absent.

Greater Romania

[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2009) |

- 1920: The Jewish population had grown to approx. 267,000.

- 1930: Romanian census registers 270,000 Jews

The Holocaust

[edit]

In 1941, the Einsatzkommandos, German mobile killing units drawn from the Nazi SS and commanded by Otto Ohlendorf entered Bessarabia. They were instrumental in the massacre of many Jews in Bessarabia, who did not flee in face of the German advance. On 8 July 1941, Mihai Antonescu, deputy prime minister and Romania's ruler at the time, made a declaration in front of the Ministers' Council:

- … With the risk of not being understood by some traditionalists which may be among you, I am in favour of the forced migration of the entire Jew element from Bessarabia and Bukovina, which must be thrown over the border. Also, I am in favor of the forced migration of the Ukrainian element, which does not belong here at this time. I don't care if we appear in history as barbarians. The Roman Empire has made a series of barbaric acts from a contemporary point of view and, still, was the greatest political settlement. There has never been a more suitable moment. If necessary, shoot with the machine gun. (This quote can be found in "The Stenograms of the Ministers' Council, Ion Antonescu's Government", vol. IV, July–September 1941 period, Bucharest, year 2000, page 57) (Stenogramele şedinţelor Consiliului de Miniştri, Guvernarea Ion Antonescu, vol. IV, perioada iulie-septembrie 1941, București, anul 2000, pagina 57).

The killing squads of Einsatzgruppe D, with special non-military units attached to the German Wehrmacht and Romanian Armies were involved in many massacres in Bessarabia (over 10,000 in a single month of war, in June–July 1941), while deporting other thousands to Transnistria. The majority (up to 2/3) of Jews from Bessarabia (207,000 as of the last census of 1930) fled before the retreat of the Soviet troops. However, 110,033 people from Bessarabia and Bukovina (the latter included at the time the counties of Cernăuţi, Storojineţ, Rădăuţi, Suceava, Câmpulung, and Dorohoi: some other 100,000 Jews) — all except a small minority of the Jews that did not flee in 1941 — were deported to Transnistria, a region that was under Romanian military control during 1941–1944.

In ghettos organized in several towns, as well as in camps (there was a comparable number of Jews from Transnistria in those camps) many people died from starvation, bad sanitation, or by being shot by special Nazi units right before the arrival of Soviet troops in 1944. The Romanian military administration of Transnistria kept very poor records of the people in the ghettos and camps. The only exact number found in Romanian sources is that 59,392 died in the ghettos and camps from the moment those were open until mid-1943.[4][self-published source?] This number includes all internees regardless of their origin, but does not include those that perished on the way to the camps, those that perished between mid-1943 and spring 1944, as well as the thousands who perished in the immediate aftermath of the Romanian army's taking control of Transnistria (see Odessa massacre).

In June–July 1941, about 10,000 (mostly civilians) were killed during the military action in the region in 1941 by German Einzatsgruppe D units and on some occasions by some Romanian troops. In Sculeni, several dozen local Jews were killed by the Romanian troops. In Bălţi around 150 local civilians were shot by Einzatsgruppe (the young women were also raped), and 14 Jewish POWs by the Romanians. In Mărculeşti, 486 Soviet POWs of Jewish origin (many conscripted locals), who were left behind by the Soviet army because of wounds, to avoid being surrounded, were shot. Approximately 40 corpses of Jews were found dumped at the outskirts of Orhei, executed either by the German or Romanian units.

From 1941 to 1942, 120,000 Jews from Bessarabia, all of Bukovina, and the Dorohoi county in Romania proper, were deported to ghettos and concentration camps in Transnistria, with only a small portion returning in 1944. The ones who died did so in the most inhuman and horrible conditions. (In the same ghettos and camps there were many Jews from that region as well, responsibility for whose death lies on the Romanian authorities that occupied it in 1941–44.)

The remainder of the 270,000 Jewish community of the region survived World War II. Mostly these were Bessarabian Jews who wisely retreated before the departure of the Soviet troops in mid-July 1941. However, the only good thing that can be said about their fate during 1941–1944 was that they survived, because the conditions under which they traveled to the interior of the USSR (e.g., to Uzbekistan) in the summer of 1941 and their conditions at their arrival were very bad. Around 15,000 Jews from Cernăuţi and further 5,000 from elsewhere in Bukovina were saved by the then-mayor of the city Traian Popovici. Nevertheless, he was not able to save everyone, and some 20,000 Bukovinian Jews were deported to Transnistria. At the end of the war, the remaining Jewish community of Bukovina decided to move to Israel.

As a result of the departure of the Romanian intellectuals in 1940 and 1944, of the Bukovinian Germans in 1940–41, of the surviving Bukovinian Jews in 1945, and of the forceful repatriation of Bukovinian Polish to Poland, Cernăuţi, one of the cultural and university "jewels" of Austria-Hungary and Romania ceased to exist as such: its population (already 100,000 in 1930) being greatly reduced. After the war, some Bukovinian Ukrainians from the countryside, as well as a few Ukrainians from Podolia and Galicia moved to the city. However, they were generally excluded from the Soviet apparatus and higher positions in the economy and administration, which was formed mostly by people known to be loyal to the Soviet system sent from eastern Ukraine or from other parts of the USSR.

Present day

[edit]

By the end of 1993, there were an estimated 15,000 Jews in the Republic of Moldova. In the same year 2,173 Jews emigrated to Israel. There were two Jewish periodical publications, both published in Chișinău. The one most widely circulated was наш голос Nash golos —אונדזער קול Undzer kol ("Our Voice"), in Yiddish and Russian.

Demographics

[edit]| Jews in Bessarabia | ||||||||||||

| County | 1817 census | 1856 census | 1897 census | 1930 census | 1941 census | 1942 | 1959 census | 1970 census | 1979 census | 1989 census | 2002, 2004 census | |

| Hotin County | N/A | N/A | c. 54,000 | 35,985 | N/A | N/A | N/A1 | N/A1 | N/A1 | N/A1 | N/A1 | Ukrainian part |

| N/A2 | N/A2 | N/A2 | N/A2 | 1072 | Moldovan part | |||||||

| Soroca County | N/A | N/A | c. 31,000 | 29,191 | N/A | N/A | N/A3 | N/A3 | N/A3 | N/A3 | 1243 | |

| Bălți County | N/A | N/A | c. 17,000 | 31,695 | N/A | N/A | N/A4 | N/A4 | N/A4 | N/A4 | 4594 | |

| Orhei County | N/A | N/A | c. 26,000 | ... | N/A | N/A | N/A5 | N/A5 | N/A5 | N/A5 | 975 | |

| Lăpușna County | N/A | N/A | c. 53,000 | ... | N/A | N/A | N/A6 | N/A6 | N/A6 | N/A6 | 2,7086 | |

| Tighina County | N/A | N/A | c. 16,000 | ... | N/A | N/A | N/A7 | N/A7 | N/A7 | N/A7 | 4377 | |

| Cahul County | N/A | N/A | c. 11,000 | 4,434 | N/A | N/A | N/A8 | N/A8 | N/A8 | N/A8 | 678 | |

| Ismail County | N/A | N/A | 6,306 | N/A | N/A | N/A9 | N/A9 | N/A9 | N/A9 | N/A9 | ||

| Cetatea Albă County | N/A | N/A | c. 11,000 | 11,390 | N/A | N/A | Ukrainian part | |||||

| N/A10 | N/A10 | N/A10 | N/A10 | 110 | Moldovan part | |||||||

| Total | 19,130 | 78,751 | 225,637[5] | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | |

1 4 districts of Chernivtsi Oblast of Ukraine

2 Briceni and Edineț Districts of Moldova

3 Ocnița, Donduşeni, Drochia, Soroca, and Floreşti districts of Moldova

4 Rîșcani, Glodeni, Fălești, Sîngerei, and Ungheni districts, and municipality of Bălți in Moldova

5 Rezina, Șoldănești, Teleneţti, Orhei, Dubăsari, and Criuleni Districts of Moldova

6 Călărași, Nisporeni, Străşeni, Ialoveni, Hînceşti districts, and municipality of Chişinău in Moldova

7 Anenii Noi, Căuşeni, Cimişlia and Basarabeasca districts, and municipality of Tighina (Bender) in Moldova

8 Leova, Cantemir, Cahul and Taraclia districts, and Gagauzia in Moldova

9 9 districts and 2 cities of Odessa Oblast of Ukraine

10 Ștefan Vodă District of Moldova

Sources:

- Recensământul General al Populaţiei României din 29 Decemvrie 1930. Vol. II: Neam, Limbă Maternă, Religie. București 1938.

- Moldovan Census (2004)

According to the 1930 Romanian Census, Jews were distributed in Bessarabia as follows:

- Hotin County: Hotin, 5,781, Briceni-Târg, 5,354, Edineţi-Târg, 5,341, Lipcani-Târg 4,693, Secureni-Târg, 4,200, Suliţa-Târg 4,152, Clişcăuţi 452, Edineţi-Sat, 398, other localities 5,614. Total: 35,985

- Soroca County: Soroca, 5,417, Zguriţa, 2,541, Briceva, 2,431, Otaci-Târg 2,781, Mărculeşti-Colonie, 2,319, Vadu-Raşcu, 1,958, Vârtejeni-Colonie, 1,834, Căpreşti-Colonie, 1,815, Dumbrăveni, 1,198, Floreştii-Noi 372, Cotiujenii Mari 367, Dondoşani-Gară, 277, Liublin-Colonie 274, Târnova, 236, Ocnița-Gară, 200, other localities 5,171. Total: 29,191

- Bălți County: Bălți, 14,229, Făleşti, 3,263, Rășcani-Târg 2,055, Ungheni-Târg, 1,368, Valea-lui-Vlad, 1,281, Sculeni-Târg, 1,204, Pârliţa-Târg, 1,064, Alexandreni-Târg, 1,018, Cornești-Târg 338, Glodeni, 212, other localities 5,663. Total: 31,695

- Orhei County:

- Lăpușna County:

- Tighina County:

- Cahul County: Leova, 2,324, Cahul, 803, Baimaclia, 509, other localities 798. Total: 4,434

- Ismail County: Chilia-Nouă, 1,952, Ismail, 1,623, Bolgrad, 1,215, Reni, 1,170, other localities 346. Total: 6,306

- Cetatea Albă County: Cetatea Albă 4,239, Tarutino, 1,546, Tatar-Bunar, 1,194, Bairamcea, 805, Volintiri 420, Arciz, 342, Sărata, 316, other localities 2,528. Total: 11,390

According to the 2004 Census, there are 4,000 Jews in the Bessarabian part of Moldova (excluding Transnistria), including:

- 2,649 in Chişinău,

- 411 in Bălți,

- 385 in Tighina (Bender),

- 548 in other localities under Chişinău control, and

- 7 in suburbs of Tighina (Bender) under Tiraspol control.

There were also 867 Jews in Transnistria, including

See also

[edit]- Batushansky

- History of the Jews in Moldova

- History of the Jews in Bukovina

- Jewish Roots in Ukraine and Moldova

- Jewish agricultural colonies in the Russian Empire

- Diana Dumitru, Moldovan researcher of the Holocaust in Bessarabia

Further reading

[edit]- Solonari, Vladimir (September 2006). ""Model province": Explaining the Holocaust of Bessarabian and Bukovinian Jewry". Nationalities Papers. 34 (4): 471–500. doi:10.1080/00905990600842106. S2CID 129413315.

- Weiner, Miriam; Ukrainian State Archives (in cooperation with); Moldovan National Archives (in cooperation with) (1999). Jewish Roots in Ukraine and Moldova: Pages from the Past and Archival Inventories. Secaucus, NJ: Miriam Weiner Routes to Roots Foundation. ISBN 978-0-96-565081-6. OCLC 607423469.

- Jews of Bessarabia on the Eve of the War (PDF). New York: William Morrow. 1993. ISBN 978-0-965-65080-9 – via Atlas of the Holocaust, rev. ed. by Sir Martin Gilbert. Reprinted with permission from the publisher

- Massacres, Deportations, and Death Marches from Bessarabia, From July 1941 (PDF). New York: William Morrow. 1993. ISBN 978-0-965-65080-9 – via Atlas of the Holocaust, rev. ed. by Sir Martin Gilbert. Reprinted with permission from the publisher

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Ion Nistor, Istoria Basarabiei, Cernăuţi, 1923, reprinted Chişinău, Cartea Moldovenească, 1991, pp. 201-02

- ^ a b Ion Nistor, pp. 208–10

- ^ "The Jewish Community of Kishinev". The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ Maresal Ion Antonescu, worldwar2.ro; accessed 27 August 2017.

- ^ "Moldova". Jewish Virtual Library.