Khoekhoe

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (December 2023) |

Khoekhoe (/ˈkɔɪkɔɪ/ KOY-koy) (or Khoikhoi in former orthography)[a] are the traditionally nomadic pastoralist indigenous population of South Africa. They are often grouped with the hunter-gatherer San (literally "Foragers") peoples.[2] The designation "Khoekhoe" is actually a kare or praise address, not an ethnic endonym, but it has been used in the literature as an ethnic term for Khoe-speaking peoples of Southern Africa, particularly pastoralist groups, such as the Griqua, Gona, Nama, Khoemana and Damara nations. The Khoekhoe were once known as Hottentots, a term now considered offensive.[3]

While the presence of Khoekhoe in Southern Africa predates the Bantu expansion, according to a scientific theory based mainly on linguistic evidence,[citation needed] it is not clear when, possibly in the Late Stone Age, the Khoekhoe began inhabiting the areas where the first contact with Europeans occurred.[2] At that time, in the 17th century, the Khoekhoe maintained large herds of Nguni cattle in the Cape region.[according to whom?][citation needed] They mostly gave up nomadic pastoralism in the 19th to 20th century.[4]

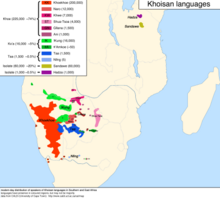

Their Khoekhoe language is related to certain dialects spoken by foraging San peoples of the Kalahari, such as the Khwe and Tshwa, forming the Khoe language family. Khoekhoe subdivisions today are the Nama people of Namibia, Botswana and South Africa (with numerous clans), the Damara of Namibia, the Orana clans of South Africa (such as Nama or Ngqosini), the Khoemana or Griqua nation of South Africa, and the Gqunukhwebe or Gona clans which fall under the Xhosa-speaking polities.[5]

The Xirikua clans (Griqua) developed their own ethnic identity in the 19th century and settled in Griqualand West. Later, they formed another independent state in Kwazulu Natal named Griqualand East, unfortunately losing their independence barely a decade later to the British. They are related to the same kinds of clan formations as Rehoboth Basters, who could also be considered a "Khoekhoe" people.[according to whom?][citation needed]

History

[edit]

Early history

[edit]The broad ethnic designation of "Khoekhoen", meaning the peoples originally part of a pastoral culture and language group to be found across Southern Africa, is thought to refer to a population originating in the northern area of modern Botswana.[citation needed] This culture steadily spread southward, eventually reaching the Cape approximately 2,000 years ago.[citation needed] "Khoekhoe" groups include ǀAwakhoen to the west, and ǀKx'abakhoena of South and mid-South Africa, and the Eastern Cape. Both of these terms mean "Red People", and are equivalent to the IsiXhosa term "amaqaba".[citation needed] Husbandry of sheep, goats and cattle grazing in fertile valleys across the region provided a stable, balanced diet, and allowed these lifestyles to spread, with larger groups forming in a region previously occupied by the subsistence foragers.[citation needed] Ntu-speaking agriculturalist culture is thought to have entered the region in the 3rd century AD, pushing pastoralists into the Western areas.[citation needed] The example of the close relation between the ǃUriǁ'aes (High clan), a cattle-keeping population, and the !Uriǁ'aeǀ'ona (High clan children), a more-or-less sedentary forager population (also known as "Strandlopers"), both occupying the area of ǁHuiǃgaeb, shows that the strict distinction between these two lifestyles is unwarranted,[citation needed] as well as the ethnic categories that are derived.[citation needed] Foraging peoples who ideologically value non-accumulation as a social value system would be distinct, however, but the distinctions among "Khoekhoe pastoralists", "San hunter-gatherers" and "Bantu agriculturalists" do not hold up to scrutiny,[misquoted][dubious – discuss] and appear to be historical reductionism.[misquoted][6]

Arrival of Europeans

[edit]Portuguese explorers and merchants are the first to record their contacts, in the 15th and 16th centuries A.D.[citation needed] The ongoing encounters were often violent.[according to whom?][citation needed] In 1510, at the Battle of Salt River, Francisco de Almeida and fifty of his men were killed and his party was defeated[7][8] by ox-mounted !Uriǁ'aekua ("Goringhaiqua" in Dutch approximate spelling), which was one of the so-called Khoekhoe clans of the area that also included the !Uriǁ'aeǀ'ona ("Goringhaicona", also known as "Strandlopers"), said to be the ancestors of the !Ora nation of today.[according to whom?][citation needed] In the late 16th century, Portuguese, French, Danish, Dutch and English but mainly Portuguese ships regularly continued to stop over in Table Bay en route to the Indies.[citation needed] They traded tobacco, copper and iron with the Khoekhoe-speaking clans of the region, in exchange for fresh meat.[citation needed]

Local population dropped after smallpox contagion was spread through European activity.[citation needed] The Khoe-speaking clans suffered high mortality as immunity to the disease was rare. This increased, as military conflict with the intensification of the colonial expansion of the United East India Company that began to enclose traditional grazing land for farms. Over the following century, the Khoe-speaking peoples were steadily driven off their land, resulting in numerous northwards migrations, and the reformulation of many nations and clans, as well as the dissolution of many traditional structures.

According to professors Robert K. Hitchcock and Wayne A. Babchuk, "During the early phases of European colonization, tens of thousands of Khoekhoe and San peoples lost their lives as a result of genocide, murder, physical mistreatment, and disease."[9]

During an investigation into "bushman hunting" parties and genocidal raids on the San, Louis Anthing commented: "I find now that the transactions are more extensive than did at first appear. I think it not unlikely that we shall find that almost all the farmers living near this border are implicated in similar acts ... At present I have only heard of coloured farmers (known as Bastards) as being mixed up with these matters."[10]

"Khoekhoe" social organisation was thus profoundly damaged by the colonial expansion and land seizure from the late 17th century onwards. As social structures broke down, many Khoekhoen settled on farms and became bondsmen (bondservants, serfs) or farm workers; others were incorporated into clans that persisted. Georg Schmidt, a Moravian Brother from Herrnhut, Saxony, now Germany, founded Genadendal in 1738, which was the first mission station in southern Africa,[11] among the Khoe-speaking peoples in Baviaanskloof in the Riviersonderend Mountains.

The colonial designation of "Baasters" came to refer to any clans that had European ancestry in some part and adopted certain Western cultural traits. Though these were later known as Griqua (Xirikua or Griekwa) they were known at the time as "Basters" and in some instances are still so called, e. g., the Bosluis Basters of the Richtersveld and the Baster community of Rehoboth, Namibia, mentioned above.

Arguably responding to the influence of missionaries, the states of Griqualand West and Griqualand East were established by the Kok dynasty; these were later absorbed into the Cape Colony of the British Empire.

Beginning in the late 18th century, Oorlam communities migrated from the Cape Colony north to Namaqualand. They settled places earlier occupied by the Nama. They came partly to escape Dutch colonial conscription, partly to raid and trade, and partly to obtain herding lands.[12] Some of these emigrant Oorlams (including the band led by the outlaw Jager Afrikaner and his son Jonker Afrikaner in the Transgariep) retained links to Oorlam communities in or close to the borders of the Cape Colony. In the face of gradual Boer expansion and then large-scale Boer migrations away from British rule at the Cape, Jonker Afrikaner brought his people into Namaqualand by the mid-19th century, becoming a formidable force for Oorlam domination over the Nama and against the Bantu-speaking Hereros for a period.[13]

Kat River settlement (1829–1856) and Khoena in the Cape Colony

[edit]

By the early 1800s, the remaining Khoe-speakers of the Cape Colony suffered from restricted civil rights and discriminatory laws on land ownership. With this pretext, the powerful Commissioner General of the Eastern Districts, Andries Stockenstrom, facilitated the creation of the "Kat River" Khoe settlement near the eastern frontier of the Cape Colony. The more cynical motive was probably to create a buffer-zone on the Cape's frontier, but the extensive fertile land in the region allowed people to own their land and build communities in peace. The settlements thrived and expanded, and Kat River quickly became a large and successful region of the Cape that subsisted more or less autonomously. The people were predominantly Afrikaans-speaking !Gonakua, but the settlement also began to attract other diverse groups.

Khoekua were known at the time for being very good marksmen, and were often invaluable allies of the Cape Colony in its frontier wars with the neighbouring Xhosa politics. In the Seventh Frontier War (1846–1847) against the Gcaleka, the Khoekua gunmen from Kat River distinguished themselves under their leader Andries Botha in the assault on the "Amatola fastnesses". (The young John Molteno, later Prime Minister, led a mixed commando in the assault, and later praised the Khoekua as having more bravery and initiative than most of his white soldiers.)[14]

However, harsh laws were still implemented in the Eastern Cape, to encourage the Khoena to leave their lands in the Kat River region and to work as labourers on white farms. The growing resentment exploded in 1850. When the Xhosa rose against the Cape Government, large numbers Khoeǀ'ona joined the Xhosa rebels for the first time.[15] After the defeat of the rebellion and the granting of representative government to the Cape Colony in 1853, the new Cape Government endeavoured to grant the Khoena political rights to avert future racial discontent. Attorney General William Porter was famously quoted as saying that he "would rather meet the Hottentot at the hustings, voting for his representative, than meet him in the wilds with his gun upon his shoulder".[16] Thus, the government enacted the Cape franchise in 1853, which decreed that all male citizens meeting a low property test, regardless of colour, had the right to vote and to seek election in Parliament. However, this non-racial principle was eroded in the late 1880s by a literacy test, and later abolished by the Apartheid Government.[17]

Massacres in German South-West Africa

[edit]From 1904 to 1907, the Germans took up arms against the Khoekhoe group living in what was then German South-West Africa, along with the Herero. Over 10,000 Nama, more than half of the total Nama population at the time, may have died in the conflict. This was the single greatest massacre ever witnessed by the Khoekhoe people.[18][19]

Apartheid

[edit]As native African people, Khoekhoe and other dark-skinned, indigenous groups were oppressed and subjugated under the white-supremacist Apartheid regime. In particular, some consider Khoekhoe and related ethnic groups to have been some of the most heavily marginalized groups during Apartheid's reign, as referenced by previous South African president Jacob Zuma in his 2012 state of the nation address.[20]

Khoekhoe were classified as "Coloured" under Apartheid. While this meant that they were offered a few privileges not given to the population deemed "black" (such as not having to carry a passbook), they were still subject to discrimination, segregation, and other forms of oppression. This included the forced relocation caused by the Group Areas Act, which broke up families and communities. The destruction of historical communities and the blanket designation of "coloured" (ignoring any nuances of the Khoekhoe peoples' specific cultures or subgroups) contributed to an erasure of Khoekhoe identity and culture, one which modern Khoekhoe people are still working to undo.[21]

Apartheid ended in 1994 and so too did the "Coloured" designation.

Modern era

[edit]After apartheid, Khoekhoe activists have worked to restore their lost culture, and affirm their ties to the land. Khoekhoe and Khoisan groups have brought cases to court demanding restitution for 'cultural genocide and discrimination against the Khoisan nation’, as well as land rights and the return of Khoesan corpses from European museums.[21]

Culture

[edit]Religion

[edit]The religious mythology of the Khoe-speaking cultures gives special significance to the Moon, which may have been viewed as the physical manifestation of a supreme being associated with heaven. Thiǁoab (Tsui'goab) is also believed to be the creator and the guardian of health, while ǁGaunab is primarily an evil being, who causes sickness or death.[22] Many Khoe-speakers have converted to Christianity and Nama Muslims make up a large percentage of Namibia's Muslims.[23]

World Heritage

[edit]UNESCO has recognised Khoe-speaking culture through its inscription of the Richtersveld as a World Heritage Site. This important area is the only place where transhumance practices associated with the culture continue to any great extent.

The International Astronomical Union named the primary component of the binary star Mu¹ Scorpii after the traditional Khoekhoe language name Xami di mûra ('eyes of the lion').[24]

List of Khoekhoe peoples

[edit]The classification of Khoekhoe peoples can be broken down roughly into two groupings: Northern Khoekhoe & Southern Khoekhoe (Cape Khoe).

Northern Khoekhoe

[edit]

The Northern Khoekhoe are referred to as the Nama or Namaqua and they have among them 11 formal clans:

- Khaiǁkhaun (Red Nation) at Hoachanas, the main group and the oldest Nama clan in Namibia[25]

- ǀKhowesen (Direct descendants of Captain Hendrik Witbooi) who was killed in the battle with Germans on 29 October 1905. The |Khowesin, reside in modern-day Gibeon under the leadership of Ismael Hendrik Witbooi the 9th Gaob (meaning captain) of the |Khowesen Gibeon, situated 72 km south of Mariental and 176 km north of Keetmanshoop just off the B1, was originally known by the name Khaxa-tsûs. It received its name from Kido Witbooi first Kaptein of the ǀKhowesin.

- ǃGamiǂnun (Bondelswarts) at Warmbad

- ǂAonin (Southern Topnaars) at Rooibank

- ǃGomen (Northern Topnaars) at Sesfontein

- ǃKharakhoen (Fransman Nama) at Gochas. After being defeated by Imperial Germany's Schutztruppe in the Battle of Swartfontein on 15 January 1905, this Nama group split into two. Part of the ǃKharakhoen fled to Lokgwabe, Botswana, and stayed there permanently,[26] the part that remained on South West African soil relocated their tribal centre to Amper-Bo. In 2016 David Hanse was inaugurated as chief of the clan.[27]

- ǁHawoben (Veldschoendragers) at Koës

- !Aman at Bethanie which was led by Cornelius Frederick

- ǁOgain (Groot Doden) at Schlip

- ǁKhauǀgoan (Swartbooi Nama) at Rehoboth, later at Salem, Ameib, and Franzfontein

- Kharoǃoan (Keetmanshoop Nama) under the leadership of Hendrik Tseib[28] split from the Red Nation in February 1850 and settled at Keetmanshoop.[25]

Among the Namaqua are also the Oorlams who are a southern Khoekhoe people of mixed-race ancestry that trekked northwards over the Orange River and where absorbed into the greater Nama identity. The Oorlams themselves are made up of five smaller clans:

- ǀAixaǀaen (Orlam Afrikaners), the first group to enter and permanently settle in Namibia. Their leader Klaas Afrikaner left the Cape Colony around 1770. The clan first built the fortress of ǁKhauxaǃnas, then moved to Blydeverwacht, and finally settled at Windhoek.[29]

- ǃAman (Bethanie Orlam) subtribe settled at Bethanie at the turn of the eighteenth century.[30]

- Kaiǀkhauan (Khauas Nama) subtribe formed in the 1830s, when the Vlermuis clan merged with the Amraal family.[30] Their home settlement became Naosanabis (now Leonardville), which they occupied from 1840 onward.[31] This clan ceased to exist after military defeat by Imperial German Schutztruppe in 1894 and 1896.[32]

- ǀHaiǀkhauan (Berseba Orlam) subtribe formed in 1850, when the Tibot and Goliath families split from the ǃAman to found Berseba.[30]

- ǀKhowesin (Witbooi Orlam) subtribe was the last to take up settlement in Namibia. They originated at Pella, south of the Orange River. Their home town became Gibeon.[30]

These Namaqua inhabit the Great Namaqualand region of Namibia. There are also minor Namaqua clans that inhabit the Little Namaqualand regions south of the Orange River in north western South Africa.

Southern Khoekhoe (Cape Khoe)

[edit]

The southern band of Khoekhoe peoples (Sometimes also called the Cape Khoe) inhabit the Western Cape and Eastern Cape Provinces in the south western coastal regions of South Africa. They are further divided into four subgroups, Eastern Cape Khoe, Central Cape Khoe, Western Cape Khoe and Peninsular Cape Khoe.[33]

The Eastern Cape Khoe

[edit]- Hoengeyqua

- Damasonqua

- Gonaqua

Central Cape Khoe

[edit]- Inqua (also called "Humcumqua")

Khoekhoe kraal, 1727 - Houtunqua

- Gamtobaqua (possible historical subgroup of the Houtunqua)

- Attaqua

- Gouriqua

- Chamaqua

Western Cape Khoe

[edit]- Chainouoqua

- Hawequa (also called "Obiqua". possible historical subgroup of the Chainouqua)

- Cochoqua

- Hessequa

- Chairiguriqua

Peninsular Cape Khoe

[edit]Goringhaiqua: The Goringhaiqua are a single tribal authority made from the two houses of the Goringhaikona and Gorachouqua.

Early European theories about Khoekhoe origins

[edit]European theories about the origins of the Khoekhoe are historically interesting in their own right. Of the European theories proposed, notable is that summarised in the commissioned Grammar and Dictionary of the Zulu Language.[34] Published in 1859, this put forward the idea of an origin from Egypt that appears to have been popular amongst men of learning in the region.[35] The reasoning for this included the (supposed) distinctive Caucasian elements of the Khoekhoe's appearance, a "wont to worship the moon'", an apparent similarity to the antiquities of Old Egypt, and a "very different language" to their neighbours. The Grammar says that "the best philologists of the present day ... find marked resemblances between the two". This conviction is echoed in an introduction to the Zulu language, which avidly often comments upon the language's various resemblances to Hebrew.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Herero and Namaqua genocide

- Nama people

- San religion

- Coloureds

- Griqua people

- History of South Africa

- Khoisan

- Sarah Baartman (1789–1815), aka "Hottentot Venus", South African Khoekhoe woman exploited as a freak show attraction in Europe

Notes

[edit]- ^ This is the native praise address, khoe-khoe "men of men" or "proper humans", as it were, from khoe "human being".[1]

Pronunciation in the Khoekhoe language: kxʰoekxʰoe.

References

[edit]- ^ "The old Dutch also did not know that their so-called Hottentots formed only one branch of a wide-spread race, of which the other branch divided into ever so many tribes, differing from each other totally in language [...] While the so-called Hottentots called themselves Khoikhoi (men of men, i.e. men par excellence), they called those other tribes Sā, the Sonqua of the Cape Records [...] We should apply the term Hottentot to the whole race, and call the two families, each by the native name, that is the one, the Khoikhoi, the so-called Hottentot proper; the other the Sān (Sā) or Bushmen." Theophilus Hahn, Tsuni-||Goam: The Supreme Being to the Khoi-Khoi (1881), p. 3.

- ^ a b Alan Barnard (1992). Hunters and Herders of Southern Africa: A Comparative Ethnography of the Khoisan Peoples. New York; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42865-1.

- ^ "Hottentot, n. and adj." OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/88829. Accessed 13 May 2018. Citing G. S. Nienaber, 'The origin of the name "Hottentot" ', African Studies, 22:2 (1963), 65–90, doi:10.1080/00020186308707174. See also Johannes Du Plessis (1917). "Report of the South African Association for the Advancement of Science". pp. 189–193. Retrieved 5 July 2010.. Strobel, Christoph (2008). "A Note on Terminology". The Testing Grounds of Modern Empire: The Making of Colonial Racial Order in the American Ohio Country and the South African Eastern Cape, 1770s–1850s. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1-4331-0123-6. Desmond, Adrian; Moore, James (2014). "Living in Slave Countries". Darwin's Sacred Cause: How a Hatred of Slavery Shaped Darwin's Views on Human Evolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-547-52775-8.Jeremy I. Levitt, ed. (2015). "Female "things" in international law". Black Women and International Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-1-107-02130-3. "Bring Back the 'Hottentot Venus'". Web.mit.edu. 15 June 1995. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2012. "Hottentot". American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Fifth ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 2011. "'Hottentot Venus' goes home". BBC News. 29 April 2002. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^

Richards, John F. (2003). "8: Wildlife and Livestock in South Africa". The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World. California World History Library. Vol. 1. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-520-93935-6. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

The nomadic pastoral Khoikhoi kraals were dispersed and their organization and culture broken. However, their successors, the trekboers and their Khoikhoi servants, managed flocks and herds similar to those of the Khoikhois. The trekboers had adapted to African-style, extensive pastoralism in this region. In order to obtain optimal pasture for their animals, early settlers imitated the Khoikhoi seasonal transhumance movements and those observed in the larger wild herbivores.

- ^ Güldemann, Tom (2006), "Structural Isoglosses between Khoekhoe and Tuu: The Cape as a Linguistic Area", Linguistic Areas, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 99–134, doi:10.1057/9780230287617_5, ISBN 978-1-349-54544-5

- ^ Alan Barnard (2008). "Ethnographic analogy and the reconstruction of early Khoekhoe society" (PDF). Southern African Humanities. 20: 61–75.

- ^ Hamilton, Carolyn; Mbenga, Bernard; Ross, Robert, eds. (2011). "Khoesan and Immigrants". The Cambridge history of South Africa: 1885–1994. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 168–173. ISBN 978-0-521-51794-2. OCLC 778617810. [verification needed]

- ^ Steenkamp, Willem (2012). Assegais, Drums & Dragoons: A Military And Social History Of The Cape. Cape Town: Jonathan Ball Publishers. pp. 2–4. ISBN 978-1-86842-479-5.

- ^ Hitchcock, Robert K.; Babchuk, Wayne A. (2017), "Genocide of Khoekhoe and San Peoples of Southern Africa", Genocide of Indigenous Peoples, pp. 143–171, doi:10.4324/9780203790830-7, ISBN 978-0-203-79083-0, retrieved 25 March 2023. "In 1652, when Europeans established a full-time presence in Southern Africa, there were some 300,000 San and 600,000 Khoekhoe in Southern Africa...There were cases of "Bushman hunting" in which commandos (mobile paramilitary units or posses) sought to dispatch San and Khoekhoe in various parts of Southern Africa"

- ^ Anthing, Louis (1 April 1862), CA, CO 4414: Louis Anthing – Colonial Secretary, pp. 10–11

- ^ Krueger, Bernhard. The Pear Tree Blossoms. Hamburg, Germany.

- ^ Omer-Cooper, J. D. (1987). History of Southern Africa. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. p. 263; Penn, Nigel (1994). "Drosters of the Bokkeveld and the Roggeveld, 1770–1800". In Elizabeth A. Eldredge; Fred Morton (eds.). Slavery in South Africa: Captive Labor on the Dutch Frontier. Boulder, CO: Westview. p. 42; Legassick, Martin (1988). "The Northern Frontier to ca. 1840: The rise and decline of the Griqua people". In Richard Elphick; Hermann Giliomee (eds.). The Shaping of South African Society, 1652–1840. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan U. Press. pp. 373–74.

- ^ Omer-Cooper, 263-64.

- ^ Molteno, P. A. (1900). The life and times of Sir John Charles Molteno, K. C. M. G., First Premier of Cape Colony, Comprising a History of Representative Institutions and Responsible Government at the Cape. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Osterhammel, Jürgen (2015). The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century. Translated by Patrick Camiller. Princeton, New Jersey; Oxford: Princeton University Press. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-691-16980-4.

- ^ Vail, Leroy, ed. (1989). The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07420-3. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ Fraser, Ashleigh (3 June 2013). "A Long Walk To Universal Franchise in South Africa". HSF.org.za. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ Jeremy Sarkin-Hughes (2008) Colonial Genocide and Reparations Claims in the 21st Century: The Socio-Legal Context of Claims under International Law by the Herero against Germany for Genocide in Namibia, 1904–1908, p. 142, Praeger Security International, Westport, Conn. ISBN 978-0-313-36256-9

- ^ Moses, A. Dirk (2008). Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation and Subaltern Resistance in World History. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-452-4.

- ^ Zuma, Jacob. "2012 – President Zuma, State of the Nation Address, 09 February 2012". sahistory.org. South African History Online. Retrieved 7 February 2024.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Francesca. "Khoisan Identity". sahistory.org. South African History Online. Retrieved 7 February 2024.

- ^ "Reconstructing the Past – the Khoikhoi: Religion and Nature".

- ^ "Islam in Namibia, making an impact". Islamonline.net.

- ^ "IAU Approves 86 New Star Names From Around the World" (Press release). IAU.org. 11 December 2017.

- ^ a b Dierks, Klaus (3 December 2004). "The historical role of the Nama nation". Die Republikein. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ Goeieman, Fred (30 November 2011). "Bridging a hundred year-old separation". Namibian Sun. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- ^ Cloete, Luqman (2 February 2016). "ǃKhara-Khoen Nama sub-clan installs leader". The Namibian.

- ^ von Schmettau, Konny (28 February 2013). "Aus "ǂNuǂgoaes" wird Keetmanshoop" ["ǂNuǂgoaes" becomes Keetmanshoop]. Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Tourismus Namibia monthly supplement. p. 10.

- ^ Dierks, Klaus. "Biographies of Namibian Personalities, A". Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d Dedering, Tilman (1997). Hate the old and follow the new: Khoekhoe and missionaries in early nineteenth-century Namibia. Vol. 2 (Missionsgeschichtliches Archiv ed.). Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 59–61. ISBN 978-3-515-06872-7. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ Dierks, Klaus. "Biographies of Namibian Personalities, L". Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ Shiremo, Shampapi (14 January 2011). "Captain Andreas Lambert: A brave warrior and a martyr of the Namibian anti-colonial resistance". New Era. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ R. Raven-Hart (1971). Cape Good Hope, 1652–1702: the first 50 years of Dutch colonisation as seen by callers. Vol. 1 & 2. Balkema, Cape Town, 1971. OCLC 835696893.

- ^ "Grammar and Dictionary of the Zulu Language". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 4: 456. 1854. doi:10.2307/592290. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 592290.

- ^ Grout, Lewis (1859). The Isizulu: a revised edition of a Grammar of the Zulu Language, etc. London: Trübner & Co.

Further reading

[edit]- P. Kolben, Present State of the Cape of Good Hope (London, 1731–38);

- A. Sparman, Voyage to the Cape of Good Hope (Perth, 1786);

- Sir John Barrow, Travels into the Interior of South Africa (London, 1801);

- Bleek, Wilhelm, Reynard the Fox in South Africa; or Hottentot Fables and Tales (London, 1864);

- Emil Holub, Seven Years in South Africa (English translation, Boston, 1881);

- G. W. Stow, Native Races of South Africa (New York, 1905);

- A. R. Colquhoun, Africander Land (New York, 1906);

- L. Schultze, Aus Namaland und Kalahari (Jena, 1907);

- Meinhof, Carl, Die Sprachen der Hamiten (Hamburg, 1912);

- Richard Elphick, Khoikhoi and the Founding of White South Africa (London, 1977)

External links

[edit]- Cultural Contact in Southern Africa by Anne Good for the Women in World History website

- An article on the history of the Khoikhoi

- Khoisan Identity on South African History Online

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Hottentots". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Hottentots". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.