Nondenominational Christianity

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (September 2023) |

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Nondenominational Christianity (or non-denominational Christianity) consists of churches, and individual Christians,[1][2] which typically distance themselves from the confessionalism or creedalism of other Christian communities[3] by not formally aligning with a specific Christian denomination.[4] According to Arizona Christian University's Cultural Research Center, nondenominational faith leaders typically maintain a biblical worldview at higher percentages than those of other Christian groups.[5]

In North America, nondenominational Christianity arose in the 18th century through the Restoration Movement, with followers organizing themselves simply as "Christians" and "Disciples of Christ".[note 1][4][6][7][8] The nondenominational movement saw expansion during the 20th century Jesus movement era, which popularized contemporary Christian music and Christian media within global pop culture.[9][10][11]

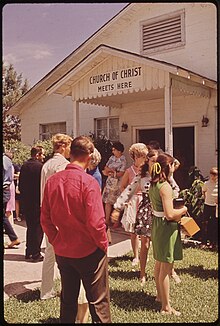

Nondenominational churches adhere to congregationalist polity, every local church is independent, take for example cowboy churches. Often congregating in loose associations such as the Churches of Christ, or in other cases founded by individual pastors such as Chuck Smith's Calvary Chapel Association, few are affiliated with historic denominations,[6] but many adhere to a form of evangelical Christianity.[12][13][14][15] Though some non-denominational churches have elder-ruled non-denominational churches have grown quite recently within networks like Acts 29.[16][17]

History[edit]

Nondenominational Christianity first arose in the 18th century through the Stone-Campbell Restoration Movement, with followers organizing themselves simply as "Christians" and "Disciples of Christ".[4][7][8] Congregations in this tradition of nondenominational Christianity often refer to themselves as Churches of Christ.[6]

Independent nondenominational churches continued to appear in the United States in the course of the 20th century.[18]

Nondenominational congregations experienced significant and continuous growth in the 21st century, particularly in the United States.[19][20] If combined into a single group, nondenominational churches collectively represented the third-largest Christian grouping in the United States in 2010, after the Roman Catholic Church and Southern Baptist Convention.[21]

In Asia, especially in Singapore and Malaysia, these churches are also more numerous, since the 1990s.[22]

Characteristics[edit]

Nondenominational churches are by definition not affiliated with any specific denominational stream of Christianity, whether by choice from their foundation or because they separated from their denomination of origin at some point in their history.[23] Like denominational congregations, nondenominational congregations vary in size, worship, and other characteristics.[24] Although independent, many nondenominational congregations choose to affiliate with a broader network of congregations.[24]

Many nondenominational churches can nevertheless be positioned in existing movements, such as Evangelicalism and Pentecostalism, even though they are autonomous and have no formal labels.[25][26][27]

Nondenominational churches are particularly visible in the megachurches.[28][29]

The neo-charismatic churches often use the term nondenominational to define themselves.[30]

Some non-denominational churches identify solely with Christianity.[31]

Criticism[edit]

Boston University religion scholar Stephen Prothero argues that nondenominationalism hides the fundamental theological and spiritual issues that initially drove the division of Christianity into denominations behind a veneer of "Christian unity". He argues that nondenominationalism encourages a descent of Christianity—and indeed, all religions—into comfortable "general moralism" rather than being a focus for facing the complexities of churchgoers' culture and spirituality. Prothero further argues that it also encourages ignorance of the Scriptures, lowering the overall religious literacy while increasing the potential for inter-religious misunderstandings and conflict.[32]

Steven R. Harmon, a Baptist theologian who supports ecumenism, argues that "there's really no such thing" as a nondenominational church, because "as soon as a supposedly non-denominational church has made decisions about what happens in worship, whom and how they will baptize, how and with what understanding they will celebrate holy communion, what they will teach, who their ministers will be and how they will be ordered, or how they relate to those churches, these decisions have placed the church within the stream of a specific type of denominational tradition".[33] Harmon argues that the cause of Christian unity is best served through denominational traditions, since each "has historical connections to the church's catholicity ... and we make progress toward unity when the denominations share their distinctive patterns of catholicity with one another".[33]

Presbyterian dogmatic theologian Amy Plantinga Pauw writes that Protestant nondenominational congregations "often seem to lack any acknowledgement of their debts and ties to larger church traditions" and argues that "for now, these non-denominational churches are living off the theological capital of more established Christian communities, including those of denominational Protestantism".[34] Pauw considers denominationalism to be a "unifying and conserving force in Christianity, nurturing and carrying forward distinctive theological traditions" (such as Wesleyanism being supported by Methodist denominations).[34]

In 2011, American evangelical professor Ed Stetzer attributed to individualism the reason for the increase in the number of evangelical churches claiming to be nondenominational Christianity.[35]

See also[edit]

- Evangelicalism

- Protestantism in the United States

- History of Protestantism in the United States

- Community Church movement

- Jesuism

- Local churches

- Non-church movement

- Non-denominational Muslim

- Non-denominational Judaism

- Postdenominationalism

- Sunday Christian

Notes[edit]

- ^ The first nondenominational Christian churches which emerged through the Stone-Campbell Restoration Movement are tied to associations such as the Churches of Christ or the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).[4][6]

References[edit]

- ^ Silliman, Daniel (2022). "'Nondenominational' Is Now the Largest Segment of American Protestants". News & Reporting. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Anderson, George M. (December 8, 2003). "Of Many Things". America Magazine. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Confessionalism is a term employed by historians to refer to "the creation of fixed identities and systems of beliefs for separate churches which had previously been more fluid in their self-understanding, and which had not begun by seeking separate identities for themselves—they had wanted to be truly Catholic and reformed." (MacCulloch, The Reformation: A History, p. xxiv.)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d The Journal of American History. Oxford University Press. 1997. p. 1400.

Richard T. Hughes, professor of religion at Pepperdine University, argues that the Churches of Christ built a corporate identity around "restoration" of the primitive church and the corresponding belief that their congregations represented a nondenominational Christianity.

- ^ Foley, Ryan (September 4, 2022). "Nondenominational pastors found to hold more biblical views than pastors of other denominations: survey". Christian Post. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Barnett, Joe R. (2020). "Who are the Churches of Christ". Southside Church of Christ. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

Not A Denomination: For this reason, we are not interested in man-made creeds, but simply in the New Testament pattern. We do not conceive of ourselves as being a denomination–nor as Catholic, Protestant, or Jewish—but simply as members of the church which Jesus established and for which he died. And that, incidentally, is why we wear his name. The term "church of Christ" is not used as a denominational designation, but rather as a descriptive term indicating that the church belongs to Christ.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hughes, Richard Thomas; Roberts, R. L. (2001). The Churches of Christ. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-313-23312-8.

Barton Stone was fully prepared to ally himself with Alexander Campbell in an effort to promote nondenominational Christianity, though it is evident that the two men came to this emphasis by very different routes.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Cherok, Richard J. (14 June 2011). Debating for God: Alexander Campbell's Challenge to Skepticism in Antebellum America. ACU Press. ISBN 978-0-89112-838-0.

Later proponents of Campbell's views would refer to themselves as the "Restoration Movement" because of the Campbellian insistence on restoring Christianity to its New Testament form. ... Added to this mix were the concepts of American egalitarianism, which gave rise to his advocacy of nondenominational individualism and local church autonomy, and Christian primitivism, which led to his promotion of such early church practices as believer's baptism by immersion and the weekly partaking of the Lord's Supper.

- ^ Young, Neil J. (August 31, 2017). "The Summer of Love ended 50 years ago. It reshaped American conservatism". Vox. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Norcross, Jonathon (March 2, 2023). "The Incredible True Story Behind 'Jesus Revolution'". Collider. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Cluver, Ross (December 13, 2021). "LoveSong: The Music. The Ministry. The Movement". CCM Magazine. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Nash, Donald A. "Why the Churches of Christ Are Not A Denomination" (PDF). The Christian Restoration Association. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Allan Anderson, An Introduction to Pentecostalism: Global Charismatic Christianity, Cambridge University Press, UK, 2013, p. 157

- ^ "Appendix B: Classification of Protestants Denominations". Pew Research Center - Religion & Public Life / America's Changing Religious Landscape. 12 May 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ Nondenominational Congregations Research at Hartford Institute for Religion Research website. Hirr.hartsem.edu. Retrieved on 2010-11-03.

- ^ "Distinctives".

- ^ "FAQ".

- ^ Roger E. Olson, The Mosaic of Christian Belief, InterVarsity Press, USA, 2016, p. 43

- ^ Aaron Earls, What Does the Growth of Nondenominationalism Mean?, research.lifeway.com, USA, August 8, 2017

- ^ Vincent Jackson, How non-denominational churches are attracting millennials, pressofatlanticcity.com, USA, February 2, 2017

- ^ Nondenominational & Independent Congregations, Hartford Seminary, Hartford Institute for Religion Research.

- ^ Peter C. Phan, Christianities in Asia, John Wiley & Sons, USA, 2011, p. 90-91

- ^ Gabriel Monet, L'Église émergente : être et faire Église en postchrétienté, LIT Verlag Münster, Switzerland, 2013, p. 135-136

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nicole K. Meidinger & Gary A. Goreharm, "Congregations, Religious" in Encyclopedia of Community: From the Village to the Virtual World (Vol. 1: eds Karen Christensen & David Levinson: SAGE, 2003), p. 333.

- ^ Pew Research Center, AMERICA'S CHANGING RELIGIOUS LANDSCAPE, pewforum.org, USA, May 12, 2015

- ^ Ed Stetzer, The rise of evangelical 'nones', cnn.com, USA, June 12, 2015

- ^ Peter C. Phan, Christianities in Asia, John Wiley & Sons, USA, 2011, p. 90

- ^ Sébastien Fath, Dieu XXL, la révolution des mégachurches, Édition Autrement, France, 2008, p. 25, 42

- ^ Bryan S. Turner, Oscar Salemink, Routledge Handbook of Religions in Asia, Routledge, UK, 2014, p. 407

- ^ Allan Anderson, An Introduction to Pentecostalism: Global Charismatic Christianity, Cambridge University Press, UK, 2013, p. 66

- ^ Walter A. Elwell, Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, Baker Academic, USA, 2001, p. 336-337

- ^ Prothero, Stephen (2007). Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know - and Doesn't. New York: HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-084670-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Steven R. Harmon, Ecumenism Means You, Too: Ordinary Christians and the Quest for Christian Unity (Cascade Books, 2010), pp. 61-62.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Amy Plantinga Pauw, "Earthen Vessels: Theological Reflections on North American Denominationalism" in Theology in Service to the Church: Global and Ecumenical Perspectives (ed. Allan Hugh Cole: Cascade Books, 2014), p. 82.

- ^ Stetzer, Ed. "Do Denominations Matter?". ChurchLeaders.com. Retrieved 30 December 2021.