Allegory

As a literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a meaning with moral or political significance. Authors have used allegory throughout history in all forms of art to illustrate or convey complex ideas and concepts in ways that are comprehensible or striking to its viewers, readers, or listeners.

Writers and speakers typically use allegories to convey (semi-) hidden or complex meanings through symbolic figures, actions, imagery, or events, which together create the moral, spiritual, or political meaning the author wishes to convey.[2] Many allegories use personification of abstract concepts.

Etymology

[edit]

First attested in English in 1382, the word allegory comes from Latin allegoria, the latinisation of the Greek ἀλληγορία (allegoría), "veiled language, figurative",[4] literally "speaking about something else",[5] which in turn comes from ἄλλος (allos), "another, different"[6] and ἀγορεύω (agoreuo), "to harangue, to speak in the assembly",[7] which originates from ἀγορά (agora), "assembly".[8]

Types

[edit]Northrop Frye discussed what he termed a "continuum of allegory", a spectrum that ranges from what he termed the "naive allegory" of the likes of The Faerie Queene, to the more private allegories of modern paradox literature.[9] In this perspective, the characters in a "naive" allegory are not fully three-dimensional, for each aspect of their individual personalities and of the events that befall them embodies some moral quality or other abstraction; the author has selected the allegory first, and the details merely flesh it out.

Classical allegory

[edit]The origins of allegory can be traced at least back to Homer in his "quasi-allegorical" use of personifications of, e.g., Terror (Deimos) and Fear (Phobos) at Il. 115 f.[10] The title of "first allegorist", however, is usually awarded to whoever was the earliest to put forth allegorical interpretations of Homer. This approach leads to two possible answers: Theagenes of Rhegium (whom Porphyry calls the "first allegorist," Porph. Quaest. Hom. 1.240.14–241.12 Schrad.) or Pherecydes of Syros, both of whom are presumed to be active in the 6th century B.C.E., though Pherecydes is earlier and as he is often presumed to be the first writer of prose. The debate is complex, since it demands we observe the distinction between two often conflated uses of the Greek verb "allēgoreīn," which can mean both "to speak allegorically" and "to interpret allegorically."[11]

In the case of "interpreting allegorically," Theagenes appears to be our earliest example. Presumably in response to proto-philosophical moral critiques of Homer (e.g., Xenophanes fr. 11 Diels-Kranz[12]), Theagenes proposed symbolic interpretations whereby the Gods of the Iliad actually stood for physical elements. So, Hephestus represents Fire, for instance (for which see fr. A2 in Diels-Kranz[13]). Some scholars, however, argue that Pherecydes cosmogonic writings anticipated Theagenes allegorical work, illustrated especially by his early placement of Time (Chronos) in his genealogy of the gods, which is thought to be a reinterpretation of the titan Kronos, from more traditional genealogies.

In classical literature two of the best-known allegories are the Cave in Plato's The Republic (Book VII) and the story of the stomach and its members in the speech of Menenius Agrippa (Livy ii. 32).

Among the best-known examples of allegory, Plato's Allegory of the Cave, forms a part of his larger work The Republic. In this allegory, Plato describes a group of people who have lived chained in a cave all of their lives, facing a blank wall (514a–b). The people watch shadows projected on the wall by things passing in front of a fire behind them and begin to ascribe forms to these shadows, using language to identify their world (514c–515a). According to the allegory, the shadows are as close as the prisoners get to viewing reality, until one of them finds his way into the outside world where he sees the actual objects that produced the shadows. He tries to tell the people in the cave of his discovery, but they do not believe him and vehemently resist his efforts to free them so they can see for themselves (516e–518a). This allegory is, on a basic level, about a philosopher who upon finding greater knowledge outside the cave of human understanding, seeks to share it as is his duty, and the foolishness of those who would ignore him because they think themselves educated enough.[14]

In Late Antiquity Martianus Capella organized all the information a fifth-century upper-class male needed to know into an allegory of the wedding of Mercury and Philologia, with the seven liberal arts the young man needed to know as guests.[15] Also, the Neoplatonic philosophy developed a type of allegorical reading of Homer[16] and Plato.[17]

Biblical allegory

[edit]Other early allegories are found in the Hebrew Bible, such as the extended metaphor in Psalm 80 of the Vine and its impressive spread and growth, representing Israel's conquest and peopling of the Promised Land.[18] Also allegorical is Ezekiel 16 and 17, wherein the capture of that same vine by the mighty Eagle represents Israel's exile to Babylon.[19]

Allegorical interpretation of the Bible was a common early Christian practice and continues. For example, the recently re-discovered Fourth Commentary on the Gospels by Fortunatianus of Aquileia has a comment by its English translator: "The principal characteristic of Fortunatianus' exegesis is a figurative approach, relying on a set of concepts associated with key terms in order to create an allegorical decoding of the text."[20]

Medieval allegory

[edit]

Allegory has an ability to freeze the temporality of a story, while infusing it with a spiritual context. Mediaeval thinking accepted allegory as having a reality underlying any rhetorical or fictional uses. The allegory was as true as the facts of surface appearances. Thus, the Papal Bull Unam Sanctam (1302) presents themes of the unity of Christendom with the pope as its head in which the allegorical details of the metaphors are adduced as facts on which is based a demonstration with the vocabulary of logic: "Therefore of this one and only Church there is one body and one head—not two heads as if it were a monster... If, then, the Greeks or others say that they were not committed to the care of Peter and his successors, they necessarily confess that they are not of the sheep of Christ." This text also demonstrates the frequent use of allegory in religious texts during the Mediaeval Period, following the tradition and example of the Bible.

In the late 15th century, the enigmatic Hypnerotomachia, with its elaborate woodcut illustrations, shows the influence of themed pageants and masques on contemporary allegorical representation, as humanist dialectic conveyed them.

The denial of medieval allegory as found in the 12th-century works of Hugh of St Victor and Edward Topsell's Historie of Foure-footed Beastes (London, 1607, 1653) and its replacement in the study of nature with methods of categorisation and mathematics by such figures as naturalist John Ray and the astronomer Galileo is thought to mark the beginnings of early modern science.[22]

Modern allegory

[edit]Since meaningful stories are nearly always applicable to larger issues, allegories may be read into many stories which the author may not have recognized. This is allegoresis, or the act of reading a story as an allegory. Examples of allegory in popular culture that may or may not have been intended include the works of Bertolt Brecht, and even some works of science fiction and fantasy, such as The Chronicles of Narnia by C. S. Lewis.

The story of the apple falling onto Isaac Newton's head is another famous allegory. It simplified the idea of gravity by depicting a simple way it was supposedly discovered. It also made the scientific revelation well known by condensing the theory into a short tale.[23]

Poetry and fiction

[edit]

While allegoresis may make discovery of allegory in any work, not every resonant work of modern fiction is allegorical, and some are clearly not intended to be viewed this way. According to Henry Littlefield's 1964 article, L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, may be readily understood as a plot-driven fantasy narrative in an extended fable with talking animals and broadly sketched characters, intended to discuss the politics of the time.[24] Yet, George MacDonald emphasized in 1893 that "A fairy tale is not an allegory."[25]

J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings is another example of a well-known work mistakenly perceived as allegorical, as the author himself once stated, "...I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history – true or feigned – with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse applicability with allegory, but one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author."[26]

Tolkien specifically resented the suggestion that the book's One Ring, which gives overwhelming power to those possessing it, was intended as an allegory of nuclear weapons. He noted that, had that been his intention, the book would not have ended with the Ring being destroyed but rather with an arms race in which various powers would try to obtain such a Ring for themselves. Then Tolkien went on to outline an alternative plot for "Lord of The Rings", as it would have been written had such an allegory been intended, and which would have made the book into a dystopia. While all this does not mean Tolkien's works may not be treated as having allegorical themes, especially when reinterpreted through postmodern sensibilities, it at least suggests that none were conscious in his writings. This further reinforces the idea of forced allegoresis, as allegory is often a matter of interpretation and only sometimes of original artistic intention.

Like allegorical stories, allegorical poetry has two meanings – a literal meaning and a symbolic meaning.

Some unique specimens of allegory can be found in the following works:

- Edmund Spenser – The Faerie Queene: The several knights in the poem actually stand for several virtues.[27]

- William Shakespeare – The Tempest: an allegory of the civilisation/barbarism binary as it pertains to colonialism

- John Bunyan – The Pilgrim's Progress: The journey of the protagonists Christian and Evangelist symbolises the ascension of the soul from earth to Heaven.

- Nathaniel Hawthorne – Young Goodman Brown: The Devil's Staff symbolises defiance of God. The characters' names, such as Goodman and Faith, ironically serve as paradox in the conclusion of the story.

- Nathaniel Hawthorne – The Scarlet Letter: The letter represents self-reliance from America's Puritan and conformity.[28]

- George Orwell – Animal Farm: The pigs stand for political figures of the Russian Revolution.[29]

- László Krasznahorkai – The Melancholy of Resistance and the film Werckmeister Harmonies: It uses a circus to describe an occupying dysfunctional government.[30]

- Edgar Allan Poe – The Masque of the Red Death: The story can be read as an allegory for humans' inability to escape death.[31]

- Arthur Miller – The Crucible: The Salem witch trials are thought to be an allegory for McCarthyism and the blacklisting of Communists in the United States of America.[32]

- Shel Silverstein – The Giving Tree: The book has been described as an allegory about relationships; between parents and children, between romantic partners, or between humans and the environment.

Art

[edit]Some elaborate and successful specimens of allegory are to be found in the following works, arranged in approximate chronological order:

- Ambrogio Lorenzetti – Allegoria del Buono e Cattivo Governo e loro Effetti in Città e Campagna (c. 1338–1339)

- Sandro Botticelli – Primavera (c. 1482)

- Albrecht Dürer – Melencolia I (1514)

- Bronzino – Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time (c. 1545)

- The English School's – "Allegory of Queen Elizabeth" (c. 1610)

- Artemisia Gentileschi – Allegory of Inclination (c. 1620), An Allegory of Peace and the Arts under the English Crown (1638); Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (c. 1638–39)

- The Feast of Herod with the Beheading of St John the Baptist by Bartholomeus Strobel is also an allegory of Europe in the time of the Thirty Years War, with portraits of many leading political and military figures.

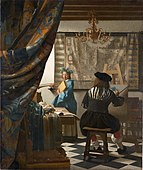

- Jan Vermeer – Allegory of Painting (c. 1666)

- Fernand Le Quesne – Allégorie de la publicité

- Jean-Léon Gérôme – Truth Coming Out of Her Well (1896)

- Graydon Parrish – The Cycle of Terror and Tragedy (2006)

- Many statues of Lady Justice: "Such visual representations have raised the question why so many allegories in the history of art, pertaining occupations once reserved for men only, are of female sex."[33]

- Damien Hirst Verity (2012)

Gallery

[edit]- Allegorical Paintings of the 16th and 17th century

-

Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia I (1514): Unused tools, an hourglass, an empty scale surrounds a female personification, with other esoteric and exoteric symbols.

-

Bronzino, Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time (c. 1545): The deities of love are surrounded by personifications of (probably) Time (a bald, man with angry eyes), Folly (the young woman-demon on the right, possibly also so old woman on the left), and others.

-

Titian, Allegory of Prudence (c. 1565–1570): The three human heads symbolise past, present and future, the characterisation of which is furthered by the triple-headed beast (wolf, lion, dog), girded by the body of a big snake.

-

The English School's Allegory of Queen Elizabeth (c. 1610), with Father Time at her right and Death looking over her left shoulder. Two cherubs are removing the weighty crown from her tired head.

-

Jan Vermeer, The Art of Painting (c. 1666): Painting is shown as related to history and politics, the young woman being Clio, the muse of history, and other symbols for the political and religious division of the Netherlands appearing.

-

Jan van Kessel, Allegory of Hearing (17th century): Diverse sources of sound, especially instruments serve as allegorical symbols.

-

Flemish August Bouttats, Allegory of Triumphant Spain with immaculist banner, c. 1682, cover of Triumphant Spain and the laureate church all over the world by the patronage of Holy Mary, Collection: Hispanic Society of America

See also

[edit]- Allegorical interpretations of Plato

- Allegorical interpretation of the Bible

- Allegory in Renaissance literature

- Allegorical sculpture

- Cultural depictions of Philip II of Spain

- Diwan (poetry)

- Freemasonry ("a system of morality veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols.")

- Parable

- Semiotics

- Theagenes of Rhegium

References

[edit]- ^ Stephen A. Barney (1989). "Allegory". Dictionary of the Middle Ages. vol. 1. ISBN 0-684-16760-3

- ^ Wheeler, L. Kip (11 January 2018). "Literary Terms and Definitions: A". Literary Vocabulary. Carson-Newman University. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz (1998). As barbas do imperador: D. Pedro II, um monarca nos trópicos . São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. p. 181. ISBN 85-7164-837-9.

- ^ ἀλληγορία, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ "Etymology of allegory by etymonline". etymonline.com. Retrieved 2024-07-04.

- ^ ἄλλος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ ἀγορεύω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ ἀγορά, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, in the Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Frye, Northrop (1957). "Second Essay: Ethical Criticism: Theory of Symbols". In Damrosch, David (ed.). Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays. Princeton Classics. Vol. 70. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press (published 2020). pp. 89ff. ISBN 9780691202563.

- ^ Small, S. G. P. (1949). "On Allegory in Homer". The Classical Journal 44 (7): 423.

- ^ Domaradzki, M. (2017). "The Beginnings of Greek Allegoresis". Classical World 110 (3):301

- ^ H. Diels and W. Kranz. (1951). Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, vol. 1. 6th edn. Berlin: Weidmann, 126–138.

- ^ H. Diels and W. Kranz. (1951). Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, vol. 1. 6th edn. Berlin: Weidmann, 51–52.

- ^ Elliott, R. K. (1967). "Socrates and Plato's Cave". Kant-Studien. 58 (2): 138. doi:10.1515/kant.1967.58.1-4.137. S2CID 170201374.

- ^ Martianus Capella and the Seven Liberal Arts – The Marriage of Philology and Mercury. Vol. II. Translated by Stahl, William Harris; Johnson, Richard; Burge, E.L. (Print ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. 1977.

- ^ Lamberton, Robert (1986). Homer the Theologian: Neoplatonist Allegorical Reading and the Growth of the Epic Tradition. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520066076. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1ppp1k.

- ^ Calian, Florin George (2013), Dolealová, Lucie; Rider, Jeff; Zironi, Alessandro (eds.), "'Clarifications' of Obscurity: Proclus' Allegorical Reading of Plato's Parmenides", Medium Aevum Quotidianum, Krems: Institut für Realienkunde des Mittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit, pp. 15–31, retrieved 2019-11-06

- ^ Kennedy, George A. (1999). Classical Rhetoric and Its Christian and Secular Tradition from Ancient to Modern Times (2nd ed.). UNC Press. p. 142. ISBN 0-8078-4769-0. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- ^ Jones, Alexander, ed. (1968). The Jerusalem Bible (Reader's ed.). Doubleday & Company. pp. 1186, 1189. ISBN 0-385-01156-3.

- ^ Fortunatianus Aquileiensis (2017). Commentary on the Gospels: English translation and introduction (PDF). De Gruyter. p. XIX. doi:10.1515/9783110516371. ISBN 978-3-11-051637-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ "Portrait of a Lady, Called Elizabeth, Lady Tanfield by Unknown Artist". ArtFund.org. Art Fund.

- ^ Harrison, Peter (2001). "Introduction". The Bible, Protestantism, and the Rise of Natural Science. Cambridge University Press. p. 1–10. ISBN 0-521-59196-1.

- ^ "Revised Memoir of Newton (Normalized Version)". The Newton Project. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ^ Littlefield, Henry (1964). "The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism". American Quarterly, 16 (1): 47–58. doi:10.2307/2710826.

- ^ Baum, L. Frank (2000). The Annotated Wizard of Oz: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Norton. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-393-04992-3.

- ^ Bogstad, Janice M.; Kaveny, Philip E., eds. (9 August 2011). Picturing Tolkien:Essays on Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings Film Trilogy. McFarland. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-7864-8473-7.

- ^ "The Faerie Queene | work by Spenser". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ "The Scarlet Letter | Summary, Analysis, Characters, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ "'Animal Farm': Andy Serkis-directed adaptation of George Orwell's allegory acquired by Netflix – Wonderfully Curated News". Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ Romm, Jake (2017-04-26). "Misery Loves Company". The New Inquiry. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ Roppolo, Joseph Patrick. "Meaning and 'The Masque of the Red Death'", collected in Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays, edited by Robert Regan. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1967. p. 137.

- ^ Sullivan, James (October 2, 2020). "What really made Salem the Witch City – The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ Cäcilia Rentmeister: The Muses, Banned From Their Occupations: Why Are There So Many Allegories Female? English summary from Kvinnovetenskaplig Tidskrift, Nr.4. 1981, Lund, Sweden as PDF. Retrieved 10.July 2011 Original Version in German: Berufsverbot für die Musen. Warum sind so viele Allegorien weiblich? In: Ästhetik und Kommunikation, Nr. 25/1976, S. 92–112. Langfassung in: Frauen und Wissenschaft. Beiträge zur Berliner Sommeruniversität für Frauen, Juli 1976, Berlin 1977, S.258–297. With illustrations. Full Texts Online: Cäcilia (Cillie) Rentmeister: publications

Further reading

[edit]- Frye, Northrop (1957) Anatomy of Criticism.

- Fletcher, Angus (1964) Allegory: The Theory of a Symbolic Mode.

- Foucault, Michel (1966) The Order of Things.

- Jain, Champat Rai (1919). The Key Of Knowledge (Second ed.). Allahabad: The Central Jaina Publishing House. Retrieved 17 November 2015 – via Internet Archive.

- Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz (1998). As barbas do imperador: D. Pedro II, um monarca nos trópicos (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. ISBN 85-7164-837-9.

External links

[edit]- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Allegory in Literary history

- Electronic Antiquity, Richard Levis, "Allegory and the Eclogues" Roman definitions of allegoria and interpreting Vergil's Eclogues.

- What is an Allegory? Introduction to Allegory