History of the Jews in Poland

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| est. 1,300,000+ | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Poland | 10,000–20,000[1][2] |

| Israel | 1,250,000 (ancestry, passport eligible[a]);[3] 202,300 (born in Poland or with a Polish-born father)[b][4] |

| Languages | |

| Polish, Hebrew, Yiddish, German | |

| Religion | |

| Judaism | |

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Jews and Judaism in Poland |

|---|

| Historical Timeline • List of Jews |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the long period of statutory religious tolerance and social autonomy which ended after the Partitions of Poland in the 18th century. During World War II there was a nearly complete genocidal destruction of the Polish Jewish community by Nazi Germany and its collaborators of various nationalities,[5] during the German occupation of Poland between 1939 and 1945, called the Holocaust. Since the fall of communism in Poland, there has been a renewed interest in Jewish culture, featuring an annual Jewish Culture Festival, new study programs at Polish secondary schools and universities, and the opening of Warsaw's Museum of the History of Polish Jews.

From the founding of the Kingdom of Poland in 1025 until the early years of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth created in 1569, Poland was the most tolerant country in Europe.[6] Historians have used the label paradisus iudaeorum (Latin for "Paradise of the Jews").[7][8] Poland became a shelter for Jews persecuted and expelled from various European countries and the home to the world's largest Jewish community of the time. According to some sources, about three-quarters of the world's Jews lived in Poland by the middle of the 16th century.[9][10][11] With the weakening of the Commonwealth and growing religious strife (due to the Protestant Reformation and Catholic Counter-Reformation), Poland's traditional tolerance began to wane from the 17th century.[12][13] After the Partitions of Poland in 1795 and the destruction of Poland as a sovereign state, Polish Jews became subject to the laws of the partitioning powers, including the increasingly antisemitic Russian Empire,[14] as well as Austria-Hungary and Kingdom of Prussia (later a part of the German Empire). When Poland regained independence in the aftermath of World War I, it was still the center of the European Jewish world, with one of the world's largest Jewish communities of over 3 million. Antisemitism was a growing problem throughout Europe in those years, from both the political establishment and the general population.[15] Throughout the interwar period, Poland supported Jewish emigration from Poland and the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. The Polish state also supported Jewish paramilitary groups such as the Haganah, Betar, and Irgun, providing them with weapons and training.[16][17]

In 1939, at the start of World War II, Poland was partitioned between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union (see Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact). One-fifth of the Polish population perished during World War II; the 3,000,000 Polish Jews murdered in the Holocaust, who constituted 90% of Polish Jewry, made up half of all Poles killed during the war.[18][19] While the Holocaust occurred largely in German-occupied Poland, it was orchestrated and perpetrated by the Nazis. Polish attitudes to the Holocaust varied widely, from actively risking death in order to save Jewish lives,[20] and passive refusal to inform on them, to indifference, blackmail,[21] and in extreme cases, committing premeditated murders such as in the Jedwabne pogrom.[22] Collaboration by non-Jewish Polish citizens in the Holocaust was sporadic, but incidents of hostility against Jews are well documented and have been a subject of renewed scholarly interest during the 21st century.[23][24][25]

In the post-war period, many of the approximately 200,000 Jewish survivors registered at the Central Committee of Polish Jews or CKŻP (of whom 136,000 arrived from the Soviet Union)[22][26][27] left the Polish People’s Republic for the nascent State of Israel or the Americas. Their departure was hastened by the destruction of Jewish institutions, post-war anti-Jewish violence, and the hostility of the Communist Party to both religion and private enterprise, but also because in 1946–1947 Poland was the only Eastern Bloc country to allow free Jewish aliyah to Israel,[28] without visas or exit permits.[29][30] Most of the remaining Jews left Poland in late 1968 as the result of the "anti-Zionist" campaign.[31] After the fall of the Communist regime in 1989, the situation of Polish Jews became normalized and those who were Polish citizens before World War II were allowed to renew Polish citizenship. The contemporary Polish Jewish community is estimated to have between 10,000 and 20,000 members.[1][2] The number of people with Jewish heritage of any sort is several times larger.[32]

Early history to Golden Age: 966–1572

Early history: 966–1385

The first Jews to visit Polish territory were traders, while permanent settlement began during the Crusades.[33] Travelling along trade routes leading east to Kyiv and Bukhara, Jewish merchants, known as Radhanites, crossed Silesia. One of them, a diplomat and merchant from the Moorish town of Tortosa in Spanish Al-Andalus, known by his Arabic name, Ibrahim ibn Yaqub, was the first chronicler to mention the Polish state ruled by Prince Mieszko I. In the summer of 965 or 966, Jacob made a trade and diplomatic journey from his native Toledo in Muslim Spain to the Holy Roman Empire and then to the Slavic countries.[34] The first actual mention of Jews in Polish chronicles occurs in the 11th century, where it appears that Jews then lived in Gniezno, at that time the capital of the Polish kingdom of the Piast dynasty. Among the first Jews to arrive in Poland in 1097 or 1098 were those banished from Prague.[34] The first permanent Jewish community is mentioned in 1085 by a Jewish scholar Jehuda ha-Kohen in the city of Przemyśl.[35]

As elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe, the principal activity of Jews in medieval Poland was commerce and trade, including the export and import of goods such as cloth, linen, furs, hides, wax, metal objects, and slaves.[36]

The first extensive Jewish migration from Western Europe to Poland occurred at the time of the First Crusade in 1098. Under Bolesław III (1102–1139), Jews, encouraged by the tolerant regime of this ruler, settled throughout Poland, including over the border in Lithuanian territory as far as Kyiv.[37] Bolesław III recognized the utility of Jews in the development of the commercial interests of his country. Jews came to form the backbone of the Polish economy. Mieszko III employed Jews in his mint as engravers and technical supervisors, and the coins minted during that period even bear Hebraic markings.[34] Jews worked on commission for the mints of other contemporary Polish princes, including Casimir the Just, Bolesław I the Tall and Władysław III Spindleshanks.[34] Jews enjoyed undisturbed peace and prosperity in the many principalities into which the country was then divided; they formed the middle class in a country where the general population consisted of landlords (developing into szlachta, the unique Polish nobility) and peasants, and they were instrumental in promoting the commercial interests of the land.

Another factor for the Jews to emigrate to Poland was the Magdeburg rights (or Magdeburg Law), a charter given to Jews, among others, that specifically outlined the rights and privileges that Jews had in Poland. For example, they could maintain communal autonomy, and live according to their own laws. This made it very attractive for Jewish communities to pick up and move to Poland.[38]

The first mention of Jewish settlers in Płock dates from 1237, in Kalisz from 1287 and a Żydowska (Jewish) street in Kraków in 1304.[34]

The tolerant situation was gradually altered by the Roman Catholic Church on the one hand, and by the neighboring German states on the other.[39] There were, however, among the reigning princes some determined protectors of the Jewish inhabitants, who considered the presence of the latter most desirable as far as the economic development of the country was concerned. Prominent among such rulers was Bolesław the Pious of Kalisz, Prince of Great Poland. With the consent of the class representatives and higher officials, in 1264 he issued a General Charter of Jewish Liberties (commonly called the Statute of Kalisz), which granted all Jews the freedom to worship, trade, and travel. Similar privileges were granted to the Silesian Jews by the local princes, Henryk IV Probus of Wrocław in 1273–90, Henryk III of Głogów in 1274 and 1299, Henryk V the Fat of Legnica in 1290–95, and Bolko III the Generous of Legnica and Wrocław in 1295.[34] Article 31 of the Statute of Kalisz tried to rein in the Catholic Church from disseminating blood libels against the Jews, by stating: "Accusing Jews of drinking Christian blood is expressly prohibited. If despite this a Jew should be accused of murdering a Christian child, such charge must be sustained by testimony of three Christians and three Jews."[40]

During the next hundred years, the Church pushed for the persecution of Jews while the rulers of Poland usually protected them.[41] The Councils of Wrocław (1267), Buda (1279), and Łęczyca (1285) each segregated Jews, ordered them to wear a special emblem, banned them from holding offices where Christians would be subordinated to them, and forbade them from building more than one prayer house in each town. However, those church decrees required the cooperation of the Polish princes for enforcement, which was generally not forthcoming, due to the profits which the Jews' economic activity yielded to the princes.[34]

In 1332, King Casimir III the Great (1303–1370) amplified and expanded Bolesław's old charter with the Wiślicki Statute. Under his reign, streams of Jewish immigrants headed east to Poland and Jewish settlements are first mentioned as existing in Lvov (1356), Sandomierz (1367), and Kazimierz near Kraków (1386).[34] Casimir, who according to a legend had a Jewish lover named Esterka from Opoczno[42] was especially friendly to the Jews, and his reign is regarded as an era of great prosperity for Polish Jewry, and was nicknamed by his contemporaries "King of the serfs and Jews." Under penalty of death, he prohibited the kidnapping of Jewish children for the purpose of enforced Christian baptism. He inflicted heavy punishment for the desecration of Jewish cemeteries. Nevertheless, while the Jews of Poland enjoyed tranquility for the greater part of Casimir's reign, toward its close they were subjected to persecution on account of the Black Death. In 1348, the first blood libel accusation against Jews in Poland was recorded, and in 1367 the first pogrom took place in Poznań.[43] Compared with the pitiless destruction of their co-religionists in Western Europe, however, Polish Jews did not fare badly; and Jewish refugees from Germany fled to the more hospitable cities in Poland.

The early Jagiellon era: 1385–1505

As a result of the marriage of Władysław II Jagiełło to Jadwiga, daughter of Louis I of Hungary, Lithuania was united with the kingdom of Poland. In 1388–1389, broad privileges were extended to Lithuanian Jews including freedom of religion and commerce on equal terms with the Christians.[44] Under the rule of Władysław II, Polish Jews had increased in numbers and attained prosperity. However, religious persecution gradually increased, as the dogmatic clergy pushed for less official tolerance, pressured by the Synod of Constance. In 1349 pogroms took place in many towns in Silesia.[34] There were accusations of blood libel by the priests, and new riots against the Jews in Poznań in 1399. Accusations of blood libel by another fanatic priest led to the riots in Kraków in 1407, although the royal guard hastened to the rescue.[44] Hysteria caused by the Black Death led to additional 14th-century outbreaks of violence against the Jews in Kalisz, Kraków and Bochnia. Traders and artisans jealous of Jewish prosperity, and fearing their rivalry, supported the harassment. In 1423, the statute of Warka forbade Jews the granting of loans against letters of credit or mortgage and limited their operations exclusively to loans made on security of moveable property.[34]

In the 14th and 15th centuries, rich Jewish merchants and moneylenders leased the royal mint, salt mines and the collecting of customs and tolls. The most famous of them were Jordan and his son Lewko of Kraków in the 14th century and Jakub Slomkowicz of Łuck, Wolczko of Drohobycz, Natko of Lviv, Samson of Zydaczow, Josko of Hrubieszów and Szania of Belz in the 15th century. For example, Wolczko of Drohobycz, King Ladislaus Jagiełło's broker, was the owner of several villages in the Ruthenian voivodship and the soltys (administrator) of the village of Werbiz. Also, Jews from Grodno were in this period owners of villages, manors, meadows, fish ponds and mills. However, until the end of the 15th century, agriculture as a source of income played only a minor role among Jewish families. More important were crafts for the needs of both their fellow Jews and the Christian population (fur making, tanning, tailoring).[34]

In 1454 anti-Jewish riots flared up in Bohemia's ethnically-German Wrocław and other Silesian cities, inspired by a Franciscan friar, John of Capistrano, who accused Jews of profaning the Christian religion. As a result, Jews were banished from Lower Silesia. Zbigniew Olesnicki then invited John to conduct a similar campaign in Kraków and several other cities, to lesser effect.

The decline in the status of the Jews was briefly checked by Casimir IV Jagiellon (1447–1492), but soon the nobility forced him to issue the Statute of Nieszawa,[45] which, among other things, abolished the ancient privileges of the Jews "as contrary to divine right and the law of the land." Nevertheless, the king continued to offer his protection to the Jews. Two years later Casimir issued another document announcing that he could not deprive the Jews of his benevolence on the basis of "the principle of tolerance which in conformity with God's laws obliged him to protect them".[46] The policy of the government toward the Jews of Poland oscillated under Casimir's sons and successors, John I Albert (1492–1501) and Alexander Jagiellon (1501–1506). In 1495, Jews were ordered out of the center of Kraków and allowed to settle in the "Jewish town" of Kazimierz. In the same year, Alexander, when he was the Grand Duke of Lithuania, followed the 1492 example of Spanish rulers and banished Jews from Lithuania. For several years they took shelter in Poland until he reversed his decision eight years later in 1503 after becoming King of Poland and allowed them back to Lithuania.[34] The next year he issued a proclamation in which he stated that a policy of tolerance befitted "kings and rulers".[46]

Center of the Jewish world: 1505–1572

Poland became more tolerant just as the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, as well as from Austria, Hungary and Germany, thus stimulating Jewish immigration to the much more accessible Poland. Indeed, with the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, Poland became the recognized haven for exiles from Western Europe; and the resulting accession to the ranks of Polish Jewry made it the cultural and spiritual center of the Jewish people.

The most prosperous period for Polish Jews began following this new influx of Jews with the reign of Sigismund I the Old (1506–1548), who protected the Jews in his realm. His son, Sigismund II Augustus (1548–1572), mainly followed his father's tolerant policy and also granted communal-administration autonomy to the Jews and laid the foundation for the power of the Qahal, or autonomous Jewish community. This period led to the creation of a proverb about Poland being a "heaven for the Jews". According to some sources, about three-quarters of all Jews lived in Poland by the middle of the 16th century.[9][10][11] In the 16h and 17th centuries, Poland welcomed Jewish immigrants from Italy, as well as Sephardi Jews and Romaniote Jews migrating there from the Ottoman Empire. Arabic-speaking Mizrahi Jews and Persian Jews also migrated to Poland during this time.[47][48][49][50] Jewish religious life thrived in many Polish communities. In 1503, the Polish monarchy appointed Rabbi Jacob Pollak the first official Rabbi of Poland.[51] By 1551, Jews were given permission to choose their own Chief Rabbi. The Chief Rabbinate held power over law and finance, appointing judges and other officials. Some power was shared with local councils. The Polish government permitted the Rabbinate to grow in power, to use it for tax collection purposes. Only 30% of the money raised by the Rabbinate served Jewish causes, the rest went to the Crown for protection. In this period Poland-Lithuania became the main center for Ashkenazi Jewry and its yeshivot achieved fame from the early 16th century.

Moses Isserles (1520–1572), an eminent Talmudist of the 16th century, established his yeshiva in Kraków. In addition to being a renowned Talmudic and legal scholar, Isserles was also learned in Kabbalah, and studied history, astronomy, and philosophy. He is considered the "Maimonides of Polish Jewry."[52] The Remuh Synagogue was built for him in 1557. Rema (רמ״א) is the Hebrew acronym for his name.[53]

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1572–1795

After the childless death of Sigismund II Augustus, the last king of the Jagiellon dynasty, nobles (szlachta) gathered at Warsaw in 1573 and signed a document in which representatives of all major religions pledged mutual support and tolerance. The following eight or nine decades of material prosperity and relative security experienced by Polish Jews – wrote Professor Gershon Hundert – witnessed the appearance of "a virtual galaxy of sparkling intellectual figures." Jewish academies were established in Lublin, Kraków, Brześć (Brisk), Lwów, Ostróg and other towns.[54] Poland-Lithuania was the only country in Europe where the Jews cultivated their own farmer's fields.[55] The central autonomous body that regulated Jewish life in Poland from the middle of the 16th to mid-18th century was known as the Council of Four Lands.[56]

Decline

Despite Warsaw Confederation agreement, it did not last for long due to beginning of Counter-Reformation in the Commonwealth and growing influence of the Jesuits.[57] By 1590s there were anti-Semitic outbreaks in Poznań, Lublin, Kraków, Vilnius and Kyiv.[57] In Lwów alone mass attacks of Jews started in 1572 and then repeated in 1592, 1613, 1618, and from 1638 every year with Jesuit students being responsible for many of them.[58] At the same time Privilegium de non tolerandis Judaeis and Privilegium de non tolerandis Christianis were introduced to limit Jews living in the Christian cities, which intensified their migration to the Eastern parts of the country where they were invited by the magnates to their private towns. By the end of the XVIIIth century two-thirds of the royal towns and cities in the Commonwealth had pressed the king to grant them that privilege.[59]

After Union of Brest in 1595-1596, Orthodox church was outlawed in Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth and that caused massive religious, social and political tensions in Ruthenia. In part it was also caused due to mass migration of the Jews to Ruthenia and their role perceived by local population[57] and in turn led to multiple Cossack uprisings. The largest one of them started in 1648 and was followed by several conflicts, in which the country lost over a third of its population (over three million people). The Jewish losses were counted in the hundreds of thousands. The first of these large-scale atrocities was the Khmelnytsky Uprising, in which the Cossacks of the Zaporozhian Host under Bohdan Khmelnytsky massacred tens of thousands of Jews as well as Catholic and Uniate population in the eastern and southern areas of Polish-occupied Ukraine.[60] The precise number of dead is not known, but the decrease of the Jewish population during this period is estimated at 100,000 to 200,000, which also includes emigration, deaths from diseases and jasyr (captivity in the Ottoman Empire). The Jewish community suffered greatly during the 1648 Ukrainian Cossack uprising which had been directed primarily against the wealthy nobility and landlords. The Jews, perceived as allies of the Poles, were also victims of the revolt, during which about 20% of them were killed.

Ruled by the elected kings of the House of Vasa since 1587, the embattled Commonwealth was invaded by the Swedish Empire in 1655 in what became known as the Deluge. Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth which had already suffered from the Khmelnytsky Uprising and from the recurring invasions of the Russians, Crimean Tatars and Ottomans, became the scene of even more atrocities. Charles X of Sweden, at the head of his victorious army, overran the cities of Kraków and Warsaw. The amount of destruction, pillage and methodical plunder during the Siege of Kraków (1657) was so enormous that parts the city never again recovered. Which was later followed by the massacres of the Crown hetman Stefan Czarniecki of the Ruthenian[61] and Jewish population.[62][63][64] He defeated the Swedes in 1660 and was equally successful in his battles against the Russians.[65] Meanwhile, the horrors of the war were aggravated by pestilence. Many Jews along with the townsfolk of Kalisz, Kraków, Poznań, Piotrków and Lublin fell victim to recurring epidemics.[66][67]

As soon as the disturbances had ceased, the Jews began to return and to rebuild their destroyed homes; and while it is true that the Jewish population of Poland had decreased, it still was more numerous than that of the Jewish colonies in Western Europe. Poland continued to be the spiritual center of Judaism. Through 1698, the Polish kings generally remained supportive of the Jews. Although Jewish losses in those events were high, the Commonwealth lost one-third of its population – approximately three million of its citizens.

The environment of the Polish Commonwealth, according to Hundert, profoundly affected Jews due to genuinely positive encounter with the Christian culture across the many cities and towns owned by the Polish aristocracy. There was no isolation.[68] The Jewish dress resembled that of their Polish neighbor. "Reports of romances, of drinking together in taverns, and of intellectual conversations are quite abundant." Wealthy Jews had Polish noblemen at their table, and served meals on silver plates.[68] By 1764, there were about 750,000 Jews in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The worldwide Jewish population at that time was estimated at 1.2 million.

In 1768, the Koliivshchyna, a rebellion in Right-bank Ukraine west of the Dnieper in Volhynia, led to ferocious murders of Polish noblemen, Catholic priests and thousands of Jews by haydamaks.[69] Four years later, in 1772, the military Partitions of Poland had begun between Russia, Prussia and Austria.[70]

The development of Judaism in Poland and the Commonwealth

The culture and intellectual output of the Jewish community in Poland had a profound impact on Judaism as a whole. Some Jewish historians have recounted that the word Poland is pronounced as Polania or Polin in Hebrew, and as transliterated into Hebrew, these names for Poland were interpreted as "good omens" because Polania can be broken down into three Hebrew words: po ("here"), lan ("dwells"), ya ("God"), and Polin into two words of: po ("here") lin ("[you should] dwell"). The "message" was that Poland was meant to be a good place for the Jews. During the time from the rule of Sigismund I the Old until the Holocaust, Poland would be at the center of Jewish religious life. Many agreed with Rabbi David HaLevi Segal that Poland was a place where "most of the time the gentiles do no harm; on the contrary they do right by Israel" (Divre David; 1689).[71]

Jewish learning

Yeshivot were established, under the direction of the rabbis, in the more prominent communities. Such schools were officially known as gymnasia, and their rabbi principals as rectors. Important yeshivot existed in Kraków, Poznań, and other cities. Jewish printing establishments came into existence in the first quarter of the 16th century. In 1530 a Torah was printed in Kraków; and at the end of the century the Jewish printing houses of that city and Lublin issued a large number of Jewish books, mainly of a religious character. The growth of Talmudic scholarship in Poland was coincident with the greater prosperity of the Polish Jews; and because of their communal autonomy educational development was wholly one-sided and along Talmudic lines. Exceptions are recorded, however, where Jewish youth sought secular instruction in the European universities. The learned rabbis became not merely expounders of the Law, but also spiritual advisers, teachers, judges, and legislators; and their authority compelled the communal leaders to make themselves familiar with the abstruse questions of Jewish law. Polish Jewry found its views of life shaped by the spirit of Talmudic and rabbinical literature, whose influence was felt in the home, in school, and in the synagogue.[citation needed]

In the first half of the 16th century the seeds of Talmudic learning had been transplanted to Poland from Bohemia, particularly from the school of Jacob Pollak, the creator of Pilpul ("sharp reasoning"). Shalom Shachna (c. 1500–1558), a pupil of Pollak, is counted among the pioneers of Talmudic learning in Poland. He lived and died in Lublin, where he was the head of the yeshivah which produced the rabbinical celebrities of the following century. Shachna's son Israel became rabbi of Lublin on the death of his father, and Shachna's pupil Moses Isserles (known as the ReMA) (1520–1572) achieved an international reputation among the Jews as the co-author of the Shulkhan Arukh, (the "Code of Jewish Law"). His contemporary and correspondent Solomon Luria (1510–1573) of Lublin also enjoyed a wide reputation among his co-religionists; and the authority of both was recognized by the Jews throughout Europe. Heated religious disputations were common, and Jewish scholars participated in them. At the same time, the Kabbalah had become entrenched under the protection of Rabbinism; and such scholars as Mordecai Jaffe and Yoel Sirkis devoted themselves to its study. This period of great Rabbinical scholarship was interrupted by the [Khmelnytsky Uprising and The Deluge.[citation needed]

The rise of Hasidism

The decade from the Khmelnytsky Uprising until after the Deluge (1648–1658) left a deep and lasting impression not only on the social life of the Polish–Lithuanian Jews, but on their spiritual life as well. The intellectual output of the Jews of Poland was reduced. The Talmudic learning which up to that period had been the common possession of the majority of the people became accessible to a limited number of students only. What religious study there was became overly formalized, some rabbis busied themselves with quibbles concerning religious laws; others wrote commentaries on different parts of the Talmud in which hair-splitting arguments were raised and discussed; and at times these arguments dealt with matters which were of no practical importance. At the same time, many miracle-workers made their appearance among the Jews of Poland, culminating in a series of false "Messianic" movements, most famously as Sabbatianism was succeeded by Frankism.[citation needed]

In this time of mysticism and overly formal Rabbinism came the teachings of Israel ben Eliezer, known as the Baal Shem Tov, or BeShT, (1698–1760), which had a profound effect on the Jews of Eastern Europe and Poland in particular. His disciples taught and encouraged the new fervent brand of Judaism based on Kabbalah known as Hasidism. The rise of Hasidic Judaism within Poland's borders and beyond had a great influence on the rise of Haredi Judaism all over the world, with a continuous influence through its many Hasidic dynasties including those of Chabad, Aleksander, Bobov, Ger, Nadvorna, among others.[citation needed]

The Partitions of Poland

In 1742 most of Silesia was lost to Prussia. Further disorder and anarchy reigned supreme in Poland during the second half of the 18th century, from the accession to the throne of its last king, Stanislaus II Augustus Poniatowski in 1764. His election was bought by Catherine the Great for 2.5 million rubles, with the Russian army stationing only 5 kilometres (3 mi) away from Warsaw.[72] Eight years later, triggered by the Confederation of Bar against Russian influence and the pro-Russian king, the outlying provinces of Poland were overrun from all sides by different military forces and divided for the first time by the three neighboring empires, Russia, Austria, and Prussia.[72] The Commonwealth lost 30% of its land during the annexations of 1772, and even more of its peoples.[73] Jews were most numerous in the territories that fell under the military control of Austria and Russia.[citation needed]

The permanent council established at the instance of the Russian government (1773–1788) served as the highest administrative tribunal, and occupied itself with the elaboration of a plan that would make practicable the reorganization of Poland on a more rational basis. The progressive elements in Polish society recognized the urgency of popular education as the first step toward reform. The famous Komisja Edukacji Narodowej ("Commission of National Education"), the first ministry of education in the world, was established in 1773 and founded numerous new schools and remodeled the old ones. One of the members of the commission, kanclerz Andrzej Zamoyski, along with others, demanded that the inviolability of their persons and property should be guaranteed and that religious toleration should be to a certain extent granted them; but he insisted that Jews living in the cities should be separated from the Christians, that those of them having no definite occupation should be banished from the kingdom, and that even those engaged in agriculture should not be allowed to possess land. On the other hand, some szlachta and intellectuals proposed a national system of government, of the civil and political equality of the Jews. This was the only example in modern Europe before the French Revolution of tolerance and broadmindedness in dealing with the Jewish question. But all these reforms were too late: a Russian army soon invaded Poland, and soon after a Prussian one followed.[citation needed]

A second partition of Poland was made on 17 July 1793. Jews, in a Jewish regiment led by Berek Joselewicz, took part in the Kościuszko Uprising the following year, when the Poles tried to again achieve independence, but were brutally put down. Following the revolt, the third and final partition of Poland took place in 1795. The territories which included the great bulk of the Jewish population was transferred to Russia, and thus they became subjects of that empire, although in the first half of the 19th century some semblance of a vastly smaller Polish state was preserved, especially in the form of the Congress Poland (1815–1831).[citation needed]

Under foreign rule many Jews inhabiting formerly Polish lands were indifferent to Polish aspirations for independence. However, most Polonized Jews supported the revolutionary activities of Polish patriots and participated in national uprisings.[74] Polish Jews took part in the November Insurrection of 1830–1831, the January Insurrection of 1863, as well as in the revolutionary movement of 1905. Many Polish Jews were enlisted in the Polish Legions, which fought for the Polish independence, achieved in 1918 when the occupying forces disintegrated following World War I.[74][75]

Jews of Poland within the Russian Empire (1795–1918)

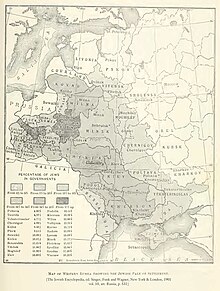

Official Russian policy would eventually prove to be substantially harsher to the Jews than that under independent Polish rule. The lands that had once been Poland were to remain the home of many Jews, as, in 1772, Catherine II, the Tzarina of Russia, instituted the Pale of Settlement, restricting Jews to the western parts of the empire, which would eventually include much of Poland, although it excluded some areas in which Jews had previously lived. By the late 19th century, over four million Jews would live in the Pale.

Tsarist policy towards the Jews of Poland alternated between harsh rules, and inducements meant to break the resistance to large-scale conversion. In 1804, Alexander I of Russia issued a "Statute Concerning Jews",[76] meant to accelerate the process of assimilation of the Empire's new Jewish population. The Polish Jews were allowed to establish schools with Russian, German or Polish curricula. However, they were also restricted from leasing property, teaching in Yiddish, and from entering Russia. They were banned from the brewing industry. The harshest measures designed to compel Jews to merge into society at large called for their expulsion from small villages, forcing them to move into towns. Once the resettlement began, thousands of Jews lost their only source of income and turned to Qahal for support. Their living conditions in the Pale began to dramatically worsen.[76]

During the reign of Tsar Nicolas I, known by the Jews as "Haman the Second", hundreds of new anti-Jewish measures were enacted.[77] The 1827 decree by Nicolas – while lifting the traditional double taxation on Jews in lieu of army service – made Jews subject to general military recruitment laws that required Jewish communities to provide 7 recruits per each 1000 "souls" every 4 years. Unlike the general population that had to provide recruits between the ages of 18 and 35, Jews had to provide recruits between the ages of 12 and 25, at the qahal's discretion. Thus between 1827 and 1857 over 30,000 children were placed in the so-called Cantonist schools, where they were pressured to convert.[78] "Many children were smuggled to Poland, where the conscription of Jews did not take effect until 1844."[77]

Pale of Settlement

The Pale of Settlement (Russian: Черта́ осе́длости, chertá osédlosti, Yiddish: תּחום-המושבֿ, tkhum-ha-moyshəv, Hebrew: תְּחוּם הַמּוֹשָב, tḥùm ha-mosháv) was the term given to a region of Imperial Russia in which permanent residency by Jews was allowed and beyond which Jewish permanent residency was generally prohibited. It extended from the eastern pale, or demarcation line, to the western Russian border with the Kingdom of Prussia (later the German Empire) and with Austria-Hungary. The archaic English term pale is derived from the Latin word palus, a stake, extended to mean the area enclosed by a fence or boundary.

With its large Catholic and Jewish populations, the Pale was acquired by the Russian Empire (which was a majority Russian Orthodox) in a series of military conquests and diplomatic maneuvers between 1791 and 1835, and lasted until the fall of the Russian Empire in 1917. It comprised about 20% of the territory of European Russia and mostly corresponded to historical borders of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth; it covered much of present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Poland, Moldova, Ukraine, and parts of western Russia.

From 1791 to 1835, and until 1917, there were differing reconfigurations of the boundaries of the Pale, such that certain areas were variously open or shut to Jewish residency, such as the Caucasus. At times, Jews were forbidden to live in agricultural communities, or certain cities, as in Kyiv, Sevastopol and Yalta, excluded from residency at a number of cities within the Pale. Settlers from outside the pale were forced to move to small towns, thus fostering the rise of the shtetls.

Although the Jews were accorded slightly more rights with the Emancipation reform of 1861 by Alexander II, they were still restricted to the Pale of Settlement and subject to restrictions on ownership and profession. The existing status quo was shattered with the assassination of Alexander in 1881 – an act falsely blamed upon the Jews.

Pogroms in the Russian Empire

The assassination prompted a large-scale wave of anti-Jewish riots, called pogroms (Russian: погро́м;) throughout 1881–1884. In the 1881 outbreak, pogroms were primarily limited to Russia, although in a riot in Warsaw two Jews were killed, 24 others were wounded, women were raped and over two million rubles worth of property was destroyed.[79][80] The new czar, Alexander III, blamed the Jews for the riots and issued a series of harsh restrictions on Jewish movements. Pogroms continued until 1884, with at least tacit government approval. They proved a turning point in the history of the Jews in partitioned Poland and throughout the world. In 1884, 36 Jewish Zionist delegates met in Katowice, forming the Hovevei Zion movement. The pogroms prompted a great wave of Jewish emigration to the United States.[81]

An even bloodier wave of pogroms broke out from 1903 to 1906, at least some of them believed to have been organized by the Tsarist Russian secret police, the Okhrana. They included the Białystok pogrom of 1906 in the Grodno Governorate of Russian Poland, in which at least 75 Jews were murdered by marauding soldiers and many more Jews were wounded. According to Jewish survivors, ethnic Poles did not participate in the pogrom and instead sheltered Jewish families.[82]

Haskalah and Halakha

The Jewish Enlightenment, Haskalah, began to take hold in Poland during the 19th century, stressing secular ideas and values. Champions of Haskalah, the Maskilim, pushed for assimilation and integration into Russian culture. At the same time, there was another school of Jewish thought that emphasized traditional study and a Jewish response to the ethical problems of antisemitism and persecution, one form of which was the Musar movement. Polish Jews generally were less influenced by Haskalah, rather focusing on a strong continuation of their religious lives based on Halakha ("rabbis's law") following primarily Orthodox Judaism, Hasidic Judaism, and also adapting to the new Religious Zionism of the Mizrachi movement later in the 19th century.

Politics in Polish territory

By the late 19th century, Haskalah and the debates it caused created a growing number of political movements within the Jewish community itself, covering a wide range of views and vying for votes in local and regional elections. Zionism became very popular with the advent of the Poale Zion socialist party as well as the religious Polish Mizrahi, and the increasingly popular General Zionists. Jews also took up socialism, forming the Bund labor union which supported assimilation and the rights of labor. The Folkspartei (People's Party) advocated, for its part, cultural autonomy and resistance to assimilation. In 1912, Agudat Israel, a religious party, came into existence.

Many Jews took part in the Polish insurrections, particularly against Russia (since the Tsars discriminated heavily against the Jews). The Kościuszko Insurrection (1794), November Insurrection (1830–31), January Insurrection (1863) and Revolutionary Movement of 1905 all saw significant Jewish involvement in the cause of Polish independence.

During the Second Polish Republic period, there were several prominent Jewish politicians in the Polish Sejm, such as Apolinary Hartglas and Yitzhak Gruenbaum. Many Jewish political parties were active, representing a wide ideological spectrum, from the Zionists, to the socialists to the anti-Zionists. One of the largest of these parties was the Bund, which was strongest in Warsaw and Lodz.

In addition to the socialists, Zionist parties were also popular, in particular, the Marxist Poale Zion and the orthodox religious Polish Mizrahi. The General Zionist party became the most prominent Jewish party in the interwar period and in the 1919 elections to the first Polish Sejm since the partitions, gained 50% of the Jewish vote.

In 1914, the German Zionist Max Bodenheimer founded the short-lived German Committee for Freeing of Russian Jews, with the goal of establishing a buffer state (Pufferstaat) within the Jewish Pale of Settlement, composed of the former Polish provinces annexed by Russia, being de facto protectorate of the German Empire that would free Jews in the region from Russian oppression. The plan, known as the League of East European States, soon proved unpopular with both German officials and Bodenheimer's colleagues, and was dead by the following year.[83][84]

Interbellum (1918–39)

Polish Jews and the struggle for Poland's independence

While most Polish Jews were neutral to the idea of a Polish state,[85] many played a significant role in the fight for Poland's independence during World War I; around 650 Jews joined the Legiony Polskie formed by Józef Piłsudski, more than all other minorities combined.[86] Prominent Jews were among the members of KTSSN, the nucleus of the interim government of re-emerging sovereign Poland including Herman Feldstein, Henryk Eile, Porucznik Samuel Herschthal, Dr. Zygmunt Leser, Henryk Orlean, Wiktor Chajes and others.[85] The donations poured in including 50,000 Austrian kronen from the Jews of Lwów and the 1,500 cans of food donated by the Blumenfeld factory among similar others.[85] A Jewish organization during the war that was opposed to Polish aspirations was the Komitee für den Osten (Kfdo)(Committee for the East) founded by German Jewish activists, which promoted the idea of Jews in the east becoming "spearhead of German expansionism" serving as "Germany's reliable vassals" against other ethnic groups in the region[87] and serving as "living wall against Poles separatists aims".[88]

In the aftermath of the Great War localized conflicts engulfed Eastern Europe between 1917 and 1919. Many attacks were launched against Jews during the Russian Civil War, the Polish–Ukrainian War, and the Polish–Soviet War ending with the Treaty of Riga. Just after the end of World War I, the West became alarmed by reports about alleged massive pogroms in Poland against Jews. Pressure for government action reached the point where U.S. President Woodrow Wilson sent an official commission to investigate the matter. The commission, led by Henry Morgenthau, Sr., concluded in its Morgenthau Report that allegations of pogroms were exaggerated.[89] It identified eight incidents in the years 1918–1919 out of 37 mostly empty claims for damages, and estimated the number of victims at 280. Four of these were attributed to the actions of deserters and undisciplined individual soldiers; none was blamed on official government policy. Among the incidents, during the battle for Pińsk a commander of Polish infantry regiment accused a group of Jewish men of plotting against the Poles and ordered the execution of thirty-five Jewish men and youth.[90] The Morgenthau Report found the charge to be "devoid of foundation" even though their meeting was illegal to the extent of being treasonable.[91] In the Lwów (Lviv) pogrom, which occurred in 1918 during the Polish–Ukrainian War of independence a day after the Poles captured Lviv from the Sich Riflemen – the report concluded – 64 Jews had been killed (other accounts put the number at 72).[92][93] In Warsaw, soldiers of Blue Army assaulted Jews in the streets, but were punished by military authorities. Many other events in Poland were later found to have been exaggerated, especially by contemporary newspapers such as The New York Times, although serious abuses against the Jews, including pogroms, continued elsewhere, especially in Ukraine.[94]

The historians Anna Cichopek-Gajraj and Glenn Dynner state that 130 pogroms of Jews occurred on Polish territories from 1918 to 1921, resulting in as many as 300 deaths, with many attacks conceived as reprisals against supposed Jewish economic power and their supposed “Judeo-Bolshevism”[95] The atrocities committed by the young Polish army and its allies in 1919 during their Kiev operation against the Bolsheviks had a profound impact on the foreign perception of the re-emerging Polish state.[96] Concerns over the fate of Poland's Jews led the Western powers to pressure Polish President Paderewski to sign the Minority Protection Treaty (the Little Treaty of Versailles), protecting the rights of minorities in new Poland including Jews and Germans.[97][98][99][100] This in turn resulted in Poland's 1921 March Constitution granting Jews the same legal rights as other citizens and guaranteed them religious tolerance and freedom of religious holidays.[101]

The number of Jews immigrating to Poland from Ukraine and Soviet Russia during the interwar period grew rapidly. Jewish population in the area of former Congress of Poland increased sevenfold between 1816 and 1921, from around 213,000 to roughly 1,500,000.[102] According to the Polish national census of 1921, there were 2,845,364 Jews living in the Second Polish Republic; but, by late 1938 that number had grown by over 16% to approximately 3,310,000. The average rate of permanent settlement was about 30,000 per annum. At the same time, every year around 100,000 Jews were passing through Poland in unofficial emigration overseas. Between the end of the Polish–Soviet War and late 1938, the Jewish population of the Republic had grown by over 464,000.[103]

Jewish and Polish culture

The newly independent Second Polish Republic had a large and vibrant Jewish minority. By the time World War II began, Poland had the largest concentration of Jews in Europe although many Polish Jews had a separate culture and ethnic identity from Catholic Poles. Some authors have stated that only about 10% of Polish Jews during the interwar period could be considered "assimilated" while more than 80% could be readily recognized as Jews.[104]

According to the 1931 National Census there were 3,130,581 Polish Jews measured by the declaration of their religion. Estimating the population increase and the emigration from Poland between 1931 and 1939, there were probably 3,474,000 Jews in Poland as of 1 September 1939 (approximately 10% of the total population) primarily centered in large and smaller cities: 77% lived in cities and 23% in the villages. They made up about 50%, and in some cases even 70% of the population of smaller towns, especially in Eastern Poland.[105] Prior to World War II, the Jewish population of Łódź numbered about 233,000, roughly one-third of the city's population.[106][better source needed] The city of Lwów (now in Ukraine) had the third-largest Jewish population in Poland, numbering 110,000 in 1939 (42%). Wilno (now in Lithuania) had a Jewish community of nearly 100,000, about 45% of the city's total.[107][better source needed] In 1938, Kraków's Jewish population numbered over 60,000, or about 25% of the city's total population.[108] In 1939 there were 375,000 Jews in Warsaw or one-third of the city's population. Only New York City had more Jewish residents than Warsaw.

Jewish youth and religious groups, diverse political parties and Zionist organizations, newspapers and theatre flourished. Jews owned land and real estate, participated in retail and manufacturing and in the export industry. Their religious beliefs spanned the range from Orthodox Hasidic Judaism to Liberal Judaism.

The Polish language, rather than Yiddish, was increasingly used by the young Warsaw Jews who did not have a problem in identifying themselves fully as Jews, Varsovians and Poles. Jews such as Bruno Schulz were entering the mainstream of Polish society, though many thought of themselves as a separate nationality within Poland. Most children were enrolled in Jewish religious schools, which used to limit their ability to speak Polish. As a result, according to the 1931 census, 79% of the Jews declared Yiddish as their first language, and only 12% listed Polish, with the remaining 9% being Hebrew.[109] In contrast, the overwhelming majority of German-born Jews of this period spoke German as their first language. During the school year of 1937–1938 there were 226 elementary schools [110] and twelve high schools as well as fourteen vocational schools with either Yiddish or Hebrew as the instructional language. Jewish political parties, both the Socialist General Jewish Labour Bund (The Bund), as well as parties of the Zionist right and left wing and religious conservative movements, were represented in the Sejm (the Polish Parliament) as well as in the regional councils.[111]

The Jewish cultural scene [112] was particularly vibrant in pre–World War II Poland, with numerous Jewish publications and more than one hundred periodicals. Yiddish authors, most notably Isaac Bashevis Singer, went on to achieve international acclaim as classic Jewish writers; Singer won the 1978 Nobel Prize in Literature. His brother Israel Joshua Singer was also a writer. Other Jewish authors of the period, such as Bruno Schulz, Julian Tuwim, Marian Hemar, Emanuel Schlechter and Bolesław Leśmian, as well as Konrad Tom and Jerzy Jurandot, were less well known internationally, but made important contributions to Polish literature. Some Polish writers had Jewish roots e.g. Jan Brzechwa (a favorite poet of Polish children). Singer Jan Kiepura, born of a Jewish mother and Polish father, was one of the most popular artists of that era, and pre-war songs of Jewish composers, including Henryk Wars, Jerzy Petersburski, Artur Gold, Henryk Gold, Zygmunt Białostocki, Szymon Kataszek and Jakub Kagan, are still widely known in Poland today. Painters became known as well for their depictions of Jewish life. Among them were Maurycy Gottlieb, Artur Markowicz, and Maurycy Trębacz, with younger artists like Chaim Goldberg coming up in the ranks.

Many Jews were film producers and directors, e.g. Michał Waszyński (The Dybbuk), Aleksander Ford (Children Must Laugh).

Scientist Leopold Infeld, mathematician Stanisław Ulam, Alfred Tarski, and professor Adam Ulam contributed to the world of science. Other Polish Jews who gained international recognition are Moses Schorr, Ludwik Zamenhof (the creator of Esperanto), Georges Charpak, Samuel Eilenberg, Emanuel Ringelblum, and Artur Rubinstein, just to name a few from the long list. The term "genocide" was coined by Rafał Lemkin (1900–1959), a Polish–Jewish legal scholar. Leonid Hurwicz was awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize in Economics. The YIVO (Jidiszer Wissenszaftlecher Institute) Scientific Institute was based in Wilno before transferring to New York during the war. In Warsaw, important centers of Judaic scholarship, such the Main Judaic Library and the Institute of Judaic Studies were located, along with numerous Talmudic Schools (Jeszybots), religious centers and synagogues, many of which were of high architectural quality. Yiddish theatre also flourished; Poland had fifteen Yiddish theatres and theatrical groups. Warsaw was home to the most important Yiddish theater troupe of the time, the Vilna Troupe, which staged the first performance of The Dybbuk in 1920 at the Elyseum Theatre. Some future Israeli leaders studied at University of Warsaw, including Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir.

There also were several Jewish sports clubs, with some of them, such as Hasmonea Lwów and Jutrzenka Kraków, winning promotion to the Polish First Football League. A Polish–Jewish footballer, Józef Klotz, scored the first ever goal for the Poland national football team. Another athlete, Alojzy Ehrlich, won several medals in the table-tennis tournaments. Many of these clubs belonged to the Maccabi World Union.[citation needed]

Between antisemitism and support for Zionism and Jewish state in Palestine

In contrast to the prevailing trends in Europe at the time, in interwar Poland an increasing percentage of Jews were pushed to live a life separate from the non-Jewish majority. The antisemitic rejection of Jews, whether for religious or racial reasons, caused estrangement and growing tensions between Jews and Poles. It is significant in this regard that in 1921, 74.2% of Polish Jews spoke Yiddish or Hebrew as their native language; by 1931, the number had risen to 87%.[113][114][109]

Besides the persistent effects of the Great Depression, the strengthening of antisemitism in Polish society was also a consequence of the influence of Nazi Germany. Following the German-Polish non-aggression pact of 1934, the antisemitic tropes of Nazi propaganda had become more common in Polish politics, where they were echoed by the National Democratic movement. One of its founders and chief ideologue Roman Dmowski was obsessed with an international conspiracy of freemasons and Jews, and in his works linked Marxism with Judaism.[116] The position of the Catholic Church had also become increasingly hostile to the Jews, who in the 1920s and 1930s were increasingly seen as agents of evil, that is, of Bolshevism.[117] Economic instability was mirrored by anti-Jewish sentiment in the press; discrimination, exclusion, and violence at the universities; and the appearance of "anti-Jewish squads" associated with some of the right-wing political parties. These developments contributed to a greater support among the Jewish community for Zionist and socialist ideas.[118]

In 1925, Polish Zionist members of the Sejm capitalized on governmental support for Zionism by negotiating an agreement with the government known as the Ugoda. The Ugoda was an agreement between the Polish prime minister Władysław Grabski and Zionist leaders of Et Liwnot, including Leon Reich. The agreement granted certain cultural and religious rights to Jews in exchange for Jewish support for Polish nationalist interests; however, the Galician Zionists had little to show for their compromise because the Polish government later refused to honor many aspects of the agreement.[119] During the 1930s, Revisionist Zionists viewed the Polish government as an ally and promoted cooperation between Polish Zionists and Polish nationalists, despite the antisemitism of the Polish government.[120]

Matters improved for a time under the rule of Józef Piłsudski (1926–1935). Piłsudski countered Endecja's Polonization with the 'state assimilation' policy: citizens were judged by their loyalty to the state, not by their nationality.[121] The years 1926–1935 were favourably viewed by many Polish Jews, whose situation improved especially under the cabinet of Pilsudski's appointee Kazimierz Bartel.[122] However, a combination of various factors, including the Great Depression,[121] meant that the situation of Jewish Poles was never very satisfactory, and it deteriorated again after Piłsudski's death in May 1935, which many Jews regarded as a tragedy.[123] The Jewish industries were negatively affected by the development of mass production and the advent of department stores offering ready-made products. The traditional sources of livelihood for the estimated 300,000 Jewish family-run businesses in the country began to vanish, contributing to a growing trend toward isolationism and internal self-sufficiency.[124] The difficult situation in the private sector led to enrolment growth in higher education. In 1923 the Jewish students constituted 62.9% of all students of stomatology, 34% of medical sciences, 29.2% of philosophy, 24.9% of chemistry and 22.1% of law (26% by 1929) at all Polish universities. It is speculated that such disproportionate numbers were the probable cause of a backlash.[125]

The interwar Polish government provided military training to the Zionist Betar paramilitary movement,[126] whose members admired the Polish nationalist camp and imitated some of its aspects.[127] Uniformed members of Betar marched and performed at Polish public ceremonies alongside Polish scouts and military, with their weapons training provided by Polish institutions and Polish military officers; Menachem Begin, one of its leaders, called for its members to defend Poland in case of war, and the organisation raised both Polish and Zionist flags.[128]

With the influence of the Endecja (National Democracy) party growing, antisemitism gathered new momentum in Poland and was most felt in smaller towns and in spheres in which Jews came into direct contact with Poles, such as in Polish schools or on the sports field. Further academic harassment, such as the introduction of ghetto benches, which forced Jewish students to sit in sections of the lecture halls reserved exclusively for them, anti-Jewish riots, and semi-official or unofficial quotas (Numerus clausus) introduced in 1937 in some universities, halved the number of Jews in Polish universities between independence (1918) and the late 1930s. The restrictions were so inclusive that – while the Jews made up 20.4% of the student body in 1928 – by 1937 their share was down to only 7.5%,[129] out of the total population of 9.75% Jews in the country according to 1931 census.[130]

While the average per capita income of Polish Jews in 1929 was 40% above the national average – which was very low compared to England or Germany – they were a very heterogeneous community, some poor, some wealthy.[131][132] Many Jews worked as shoemakers and tailors, as well as in the liberal professions; doctors (56% of all doctors in Poland), teachers (43%), journalists (22%) and lawyers (33%).[133] In 1929, about a third of artisans and home workers and a majority of shopkeepers were Jewish.[134]

Although many Jews were educated, they were almost completely excluded from government jobs; as a result, the proportion of unemployed Jewish salary earners was approximately four times as great in 1929 as the proportion of unemployed non-Jewish salary earners, a situation compounded by the fact that almost no Jews were on government support.[135] In 1937 the Catholic trade unions of Polish doctors and lawyers restricted their new members to Christian Poles.[136] In a similar manner, the Jewish trade unions excluded non-Jewish professionals from their ranks after 1918.[citation needed] The bulk of Jewish workers were organized in the Jewish trade unions under the influence of the Jewish socialists who split in 1923 to join the Communist Party of Poland and the Second International.[137][138]

Anti-Jewish sentiment in Poland had reached its zenith in the years leading to the Second World War.[139] Between 1935 and 1937 seventy-nine Jews were killed and 500 injured in anti-Jewish incidents.[140] National policy was such that the Jews who largely worked at home and in small shops were excluded from welfare benefits.[141] In the provincial capital of Łuck Jews constituted 48.5% of the diverse multiethnic population of 35,550 Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians and others.[142] Łuck had the largest Jewish community in the voivodeship.[143] In the capital of Brześć in 1936 Jews constituted 41.3% of general population and some 80.3% of private enterprises were owned by Jews.[144][145] The 32% of Jewish inhabitants of Radom enjoyed considerable prominence also,[146] with 90% of small businesses in the city owned and operated by the Jews including tinsmiths, locksmiths, jewellers, tailors, hat makers, hairdressers, carpenters, house painters and wallpaper installers, shoemakers, as well as most of the artisan bakers and clock repairers.[147] In Lubartów, 53.6% of the town's population were Jewish also along with most of its economy.[148] In a town of Luboml, 3,807 Jews lived among its 4,169 inhabitants, constituting the essence of its social and political life.[142]

The national boycott of Jewish businesses and advocacy for their confiscation was promoted by the National Democracy party and Prime Minister Felicjan Sławoj-Składkowski, declared an "economic war against Jews",[149] while introducing the term "Christian shop". As a result a boycott of Jewish businesses grew intensively. A national movement to prevent the Jews from kosher slaughter of animals, with animal rights as the stated motivation, was also organized.[150] Violence was also frequently aimed at Jewish stores, and many of them were looted. At the same time, persistent economic boycotts and harassment, including property-destroying riots, combined with the effects of the Great Depression that had been very severe on agricultural countries like Poland, reduced the standard of living of Poles and Polish Jews alike to the extent that by the end of the 1930s, a substantial portion of Polish Jews lived in grinding poverty.[151] As a result, on the eve of the Second World War, the Jewish community in Poland was large and vibrant internally, yet (with the exception of a few professionals) also substantially poorer and less integrated than the Jews in most of Western Europe.[citation needed]

The main strain of antisemitism in Poland during this time was motivated by Catholic religious beliefs and centuries-old myths such as the blood libel. This religious-based antisemitism was sometimes joined with an ultra-nationalistic stereotype of Jews as disloyal to the Polish nation.[152] On the eve of World War II, many typical Polish Christians believed that there were far too many Jews in the country, and the Polish government became increasingly concerned with the "Jewish question". According to the British Embassy in Warsaw, in 1936 emigration was the only solution to the Jewish question that found wide support in all Polish political parties.[153] The Polish government condemned wanton violence against the Jewish minority, fearing international repercussions, but shared the view that the Jewish minority hindered Poland's development; in January 1937 Foreign Minister Józef Beck declared that Poland could house 500,000 Jews, and hoped that over the next 30 years 80,000-100,000 Jews a year would leave Poland.[154]

As the Polish government sought to lower the numbers of the Jewish population in Poland through mass emigration, it embraced close and good contact with Ze'ev Jabotinsky, the founder of Revisionist Zionism, and pursued a policy of supporting the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine.[155] The Polish government hoped Palestine would provide an outlet for its Jewish population and lobbied for creation of a Jewish state in the League of Nations and other international venues, proposing increased emigration quotas[156] and opposing the Partition Plan of Palestine on behalf of Zionist activists.[157] As Jabotinsky envisioned in his "Evacuation Plan" the settlement of 1.5 million East European Jews within 10 years in Palestine, including 750,000 Polish Jews, he and Beck shared a common goal.[158] Ultimately this proved impossible and illusory, as it lacked both general Jewish and international support.[159] In 1937 Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs Józef Beck declared in the League of Nations his support for the creation of a Jewish state and for an international conference to enable Jewish emigration.[160] The common goals of the Polish state and of the Zionist movement, of increased Jewish population flow to Palestine, resulted in their overt and covert cooperation. Poland helped by organizing passports and facilitating illegal immigration, and supplied the Haganah with weapons.[161] Poland also provided extensive support to the Irgun (the military branch of the Revisionist Zionist movement) in the form of military training and weapons. According to Irgun activists, the Polish state supplied the organisation with 25,000 rifles, additional material and weapons, and by summer 1939 Irgun's Warsaw warehouses held 5,000 rifles and 1,000 machine guns. The training and support by Poland would allow the organisation to mobilise 30,000-40,000 men.[162]

In 1938, the Polish government revoked Polish citizenship from tens-of-thousands Polish Jews who had lived outside the country for an extended period of time.[163] It was feared that many Polish Jews living in Germany and Austria would want to return en masse to Poland to escape anti-Jewish measures. Their property was claimed by the Polish state.[149]

By the time of the German invasion in 1939, antisemitism was escalating, and hostility towards Jews was a mainstay of the right-wing political forces post-Piłsudski regime and also the Catholic Church. Discrimination and violence against Jews had rendered the Polish Jewish population increasingly destitute. Despite the impending threat to the Polish Republic from Nazi Germany, there was little effort seen in the way of reconciliation with Poland's Jewish population. In July 1939 the pro-government Gazeta Polska wrote, "The fact that our relations with the Reich are worsening does not in the least deactivate our program in the Jewish question—there is not and cannot be any common ground between our internal Jewish problem and Poland's relations with the Hitlerite Reich."[164][165] Escalating hostility towards Polish Jews and an official Polish government desire to remove Jews from Poland continued until the German invasion of Poland.[166]

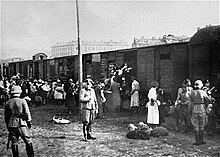

World War II and the destruction of Polish Jewry (1939–45)

Polish September Campaign

The number of Jews in Poland on 1 September 1939, amounted to about 3,474,000 people.[167] One hundred thirty thousand soldiers of Jewish descent, including Boruch Steinberg, Chief Rabbi of the Polish Military, served in the Polish Army at the outbreak of the Second World War,[168] thus being among the first to launch armed resistance against Nazi Germany.[169] During the September Campaign some 20,000 Jewish civilians and 32,216 Jewish soldiers were killed,[170] while 61,000 were taken prisoner by the Germans;[171] the majority did not survive. The soldiers and non-commissioned officers who were released ultimately found themselves in the Nazi ghettos and labor camps and suffered the same fate as other Jewish civilians in the ensuing Holocaust in Poland. In 1939, Jews constituted 30% of Warsaw's population.[172] With the coming of the war, Jewish and Polish citizens of Warsaw jointly defended the city, putting their differences aside.[172] Polish Jews later served in almost all Polish formations during the entire World War II, many were killed or wounded and very many were decorated for their combat skills and exceptional service. Jews fought with the Polish Armed Forces in the West, in the Soviet formed Polish People's Army as well as in several underground organizations and as part of Polish partisan units or Jewish partisan formations.[173]

Territories annexed by the USSR (1939–1941)

The Soviet Union signed a Pact with Nazi Germany on 23 August 1939 containing a protocol about partition of Poland (generally known but denied by the Soviet Union for the next 50 years).[174] The German army attacked Poland on 1 September 1939. The Soviet Union followed suit by invading eastern Poland on 17 September 1939. The days between the retreat of the Polish army and the entry of the Red Army, September 18–21, witnessed a pogrom in Grodno, in which 25 Jews were killed (the Soviets later put some of the pogromists on trial).[175]

Within weeks, 61.2% of Polish Jews found themselves under the German occupation, while 38.8% were trapped in the Polish areas annexed by the Soviet Union.[163] Jews under German occupation were immediately maltreated, beaten, publicly executed, and even burnt alive in the synagogue.[163] As a result 350,000 Polish Jews fled from the German-occupied area to the Soviet area.[176][177] Upon annexing the region, the Soviet government recognized as Soviet citizens Jews (and other non-Poles) who were permanent residents of the area, while offering refugees the choice of either taking on Soviet citizenship or returning to their former homes.[177]

The Soviet annexation was accompanied by the widespread arrests of government officials, police, military personnel, border guards, teachers, priests, judges etc., followed by the NKVD prisoner massacres and massive deportation of 320,000 Polish nationals to the Soviet interior and the Gulag slave labor camps where, as a result of the inhuman conditions, about half of them died before the end of war.[178]

Jewish refugees under the Soviet occupation had little knowledge about what was going on under the Germans since the Soviet media did not report on the goings-on in territories occupied by their Nazi ally.[179][180][181][pages needed] Many people from Western Poland registered for repatriation back to the German zone, including wealthier Jews, as well as some political and social activists from the interwar period.[citation needed]

Synagogues and churches were not yet closed but heavily taxed. The Soviet ruble of little value was immediately equalized to the much higher Polish zloty and by the end of 1939, zloty was abolished.[182] Most economic activity became subject to central planning and the NKVD restrictions. Since the Jewish communities tended to rely more on commerce and small-scale businesses, the confiscations of property affected them to a greater degree than the general populace. The Soviet rule resulted in near collapse of the local economy, characterized by insufficient wages and general shortage of goods and materials. The Jews, like other inhabitants of the region, saw a fall in their living standards.[176][182]

Under the Soviet policy, ethnic Poles were dismissed and denied access to positions in the civil service. Former senior officials and notable members of the Polish community were arrested and exiled together with their families.[183][184] At the same time the Soviet authorities encouraged young Jewish communists to fill in the newly emptied government and civil service jobs.[182][185]

While most eastern Poles consolidated themselves around the anti-Soviet sentiments,[186] a portion of the Jewish population, along with the ethnic Belarusian and Ukrainian activists had welcomed invading Soviet forces as their protectors.[187][188][189] The general feeling among the Polish Jews was a sense of temporary relief in having escaped the Nazi occupation in the first weeks of war.[93][190] The Polish poet and former communist Aleksander Wat has stated that Jews were more inclined to cooperate with the Soviets.[191][192] Following Jan Karski's report written in 1940, historian Norman Davies claimed that among the informers and collaborators, the percentage of Jews was striking; likewise, General Władysław Sikorski estimated that 30% of them identified with the communists whilst engaging in provocations; they prepared lists of Polish "class enemies".[185][191] Other historians have indicated that the level of Jewish collaboration could well have been less than suggested.[193] Historian Martin Dean has written that "few local Jews obtained positions of power under Soviet rule."[194]

The issue of Jewish collaboration with the Soviet occupation remains controversial. Some scholars note that while not pro-Communist, many Jews saw the Soviets as the lesser threat compared to the German Nazis. They stress that stories of Jews welcoming the Soviets on the streets, vividly remembered by many Poles from the eastern part of the country are impressionistic and not reliable indicators of the level of Jewish support for the Soviets. Additionally, it has been noted that some ethnic Poles were as prominent as Jews in filling civil and police positions in the occupation administration, and that Jews, both civilians and in the Polish military, suffered equally at the hands of the Soviet occupiers.[195] Whatever initial enthusiasm for the Soviet occupation Jews might have felt was soon dissipated upon feeling the impact of the suppression of Jewish societal modes of life by the occupiers.[196] The tensions between ethnic Poles and Jews as a result of this period has, according to some historians, taken a toll on relations between Poles and Jews throughout the war, creating until this day, an impasse to Polish–Jewish rapprochement.[189]

A number of younger Jews, often through the pro-Marxist Bund or some Zionist groups, were sympathetic to Communism and Soviet Russia, both of which had been enemies of the Polish Second Republic. As a result of these factors they found it easy after 1939 to participate in the Soviet occupation administration in Eastern Poland, and briefly occupied prominent positions in industry, schools, local government, police and other Soviet-installed institutions. The concept of "Judeo-communism" was reinforced during the period of the Soviet occupation (see Żydokomuna).[197][198]

There were also Jews who assisted Poles during the Soviet occupation. Among the thousands of Polish officers killed by the Soviet NKVD in the Katyń massacre there were 500–600 Jews. From 1939 to 1941 between 100,000 and 300,000 Polish Jews were deported from Soviet-occupied Polish territory into the Soviet Union. Some of them, especially Polish Communists (e.g. Jakub Berman), moved voluntarily; however, most of them were forcibly deported or imprisoned in a Gulag. Small numbers of Polish Jews (about 6,000) were able to leave the Soviet Union in 1942 with the Władysław Anders army, among them the future Prime Minister of Israel Menachem Begin. During the Polish army's II Corps' stay in the British Mandate of Palestine, 67% (2,972) of the Jewish soldiers deserted to settle in Palestine, and many joined the Irgun. General Anders decided not to prosecute the deserters and emphasized that the Jewish soldiers who remained in the Force fought bravely.[199] The Cemetery of Polish soldiers who died during the Battle of Monte Cassino includes headstones bearing a Star of David. A number of Jewish soldiers died also when liberating Bologna.[200]

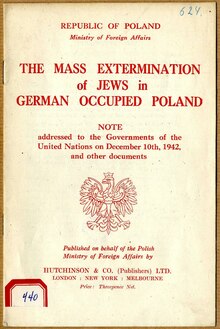

The Holocaust

Poland's Jewish community suffered the most in the Holocaust. Some six million Polish citizens perished in the war[201] – half of those (three million Polish Jews, all but some 300,000 of the Jewish population) being killed at the German extermination camps at Auschwitz, Treblinka, Majdanek, Belzec, Sobibór, and Chełmno or starved to death in the ghettos.[202]

Poland was where the German program of extermination of Jews, the "Final Solution", was implemented, since this was where most of Europe's Jews (excluding the Soviet Union's) lived.[203]

In 1939 several hundred synagogues were blown up or burned by the Germans, who sometimes forced the Jews to do it themselves.[167] In many cases, the Germans turned the synagogues into factories, places of entertainment, swimming pools, or prisons.[167] By war's end, almost all the synagogues in Poland had been destroyed.[204] Rabbis were forced to dance and sing in public with their beards shorn off. Some rabbis were set on fire or hanged.[167]

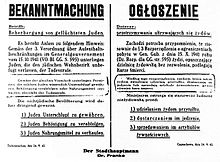

The Germans ordered that all Jews be registered, and the word "Jude" was stamped in their identity cards.[205] Numerous restrictions and prohibitions targeting Jews were introduced and brutally enforced.[206] For example, Jews were forbidden to walk on the sidewalks,[207] use public transport, or enter places of leisure, sports arenas, theaters, museums and libraries.[208] On the street, Jews had to lift their hat to passing Germans.[209] By the end of 1941 all Jews in German-occupied Poland, except the children, had to wear an identifying badge with a blue Star of David.[210][211] Rabbis were humiliated in "spectacles organised by the German soldiers and police" who used their rifle butts "to make these men dance in their praying shawls."[212] The Germans "disappointed that Poles refused to collaborate",[213] made little attempts to set up a collaborationist government in Poland,[214][215][216] nevertheless, German tabloids printed in Polish routinely ran antisemitic articles that urged local people to adopt an attitude of indifference towards the Jews.[217]

Following Operation Barbarossa, many Jews in what was then Eastern Poland fell victim to Nazi death squads called Einsatzgruppen, which massacred Jews, especially in 1941. Some of these German-inspired massacres were carried out with help from, or active participation of Poles themselves: for example, the Jedwabne pogrom, in which between 300 (Institute of National Remembrance's Final Findings[218]) and 1,600 Jews (Jan T. Gross) were tortured and beaten to death by members of the local population. The full extent of Polish participation in the massacres of the Polish Jewish community remains a controversial subject, in part due to Jewish leaders' refusal to allow the remains of the Jewish victims to be exhumed and their cause of death to be properly established. The Polish Institute for National Remembrance identified twenty-two other towns that had pogroms similar to Jedwabne.[219] The reasons for these massacres are still debated, but they included antisemitism, resentment over alleged cooperation with the Soviet invaders in the Polish–Soviet War and during the 1939 invasion of the Kresy regions, greed for the possessions of the Jews, and of course coercion by the Nazis to participate in such massacres.

Some Jewish historians have written of the negative attitudes of some Poles towards persecuted Jews during the Holocaust.[220] While members of Catholic clergy risked their lives to assist Jews, their efforts were sometimes made in the face of antisemitic attitudes from the church hierarchy.[221][222] Anti-Jewish attitudes also existed in the London-based Polish Government in Exile,[223] although on 18 December 1942 the President in exile Władysław Raczkiewicz wrote a dramatic letter to Pope Pius XII, begging him for a public defense of both murdered Poles and Jews.[224] In spite of the introduction of death penalty extending to the entire families of rescuers, the number of Polish Righteous among the Nations testifies to the fact that Poles were willing to take risks in order to save Jews.[225]