Pasargadae

پاسارگاد | |

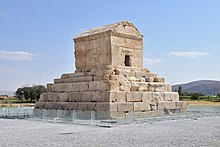

Tomb of Cyrus the Great in Pasargadae | |

| Location | Fars Province, Iran |

|---|---|

| Region | Iran |

| Coordinates | 30°12′00″N 53°10′46″E / 30.20000°N 53.17944°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Builder | Cyrus the Great |

| Material | Stone, clay |

| Founded | 6th century BCE |

| Periods | Achaemenid Empire |

| Cultures | Persian |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | Ali Sami, David Stronach, Ernst Herzfeld |

| Condition | In ruins |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) |

| Reference | 1106 |

| Inscription | 2004 (28th Session) |

| Area | 160 ha (0.62 sq mi) |

| Buffer zone | 7,127 ha (27.52 sq mi) |

Pasargadae /pə'sɑrgədi/ (from Pāθra-gadā, lit. 'protective club' or 'strong club';[1] Modern Persian: پاسارگاد Pāsārgād) was the capital of the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great (559–530 BC). Today it is an archaeological site located just north of the town of Madar-e-Soleyman and about 90 kilometres (56 mi) to the northeast of the modern city of Shiraz. It is one of Iran's UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[2] It is considered to be the location of the Tomb of Cyrus, a tomb previously attributed to Madar-e-Soleyman, the "Mother of Solomon". Currently it is a national tourist site administered by the Iranian culture of world heritage.

History

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2019) |

Pasargadae was founded in the 6th century BCE as the first capital of the Achaemenid Empire by Cyrus the Great, near the site of his victory over the Median king Astyages in 550 BCE. The city remained the Achaemenid capital until Darius moved it to Persepolis.[3]

The archaeological site covers 1.6 square kilometres (0.62 sq mi) and includes a structure commonly believed to be the mausoleum of Cyrus, the fortress of Toll-e Takht sitting on top of a nearby hill, and the remains of two royal palaces and gardens. Pasargadae Persian Gardens provide the earliest known example of the Persian chahar bagh, or fourfold garden design (see Persian Gardens).

The remains of the tomb of Cyrus' son and successor Cambyses II have been found in Pasargadae, near the fortress of Toll-e Takht, and identified in 2006.[4]

The Gate R, located at the eastern edge of the palace area, is the oldest known freestanding propylaeum. It may have been the architectural predecessor of the Gate of All Nations at Persepolis.[5]

Tomb of Cyrus the Great

[edit]

The most important monument in Pasargadae is the tomb of Cyrus the Great. It has six broad steps leading to the sepulchre, the chamber of which measures 3.17 metres (10.4 ft) long by 2.11 metres (6 ft 11 in) wide by 2.11 metres (6 ft 11 in) high and has a low and narrow entrance. Though there is no firm evidence identifying the tomb as that of Cyrus, Greek historians say that Alexander believed it was. When Alexander looted and destroyed Persepolis, he paid a visit to the tomb of Cyrus. Arrian, writing in the second century CE, recorded that Alexander commanded Aristobulus, one of his warriors, to enter the monument. Inside he found a golden bed, a table set with drinking vessels, a gold coffin, some ornaments studded with precious stones and an inscription on the tomb. No trace of any such inscription survives, and there is considerable disagreement about the exact wording of the text. Strabo and Arrian report that it reads:[6]

Passer-by, I am Cyrus, who gave the Persians an empire, and was king of Asia.

Grudge me not therefore this monument.

The design of Cyrus' tomb is credited to Mesopotamian or Elamite ziggurats, but the cella is usually attributed to Urartu tombs of an earlier period.[7] In particular, the tomb at Pasargadae has almost exactly the same dimensions as the tomb of Alyattes, father of the Lydian King Croesus; however, some have refused the claim (according to Herodotus, Croesus was spared by Cyrus during the conquest of Lydia, and became a member of Cyrus' court). The main decoration on the tomb is a rosette design over the door within the gable.[8] In general, the art and architecture found at Pasargadae exemplified the Persian synthesis of various traditions, drawing on precedents from Elam, Babylon, Assyria, and ancient Egypt, with the addition of some Anatolian influences.

Archaeology

[edit]

The first capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Pasargadae lies in ruins 40 kilometers from Persepolis, in present-day Fars province of Iran.[9] Gardens were of great significance in Persian culture, and the palace complex was constituted by an extensive pattern of gardens stretching from the Tomb of Cyrus to a fortress known as the Tall-i Takht, about three kilometres away, and containing various palaces and other buildings. The architecture showed elements of Elamite and Egyptian or Phoenician decoration as well as Ionian Greek building techniques, suggesting a desire by Cyrus to reflect his imperial rather than simply national kingship.[10]

Pasargadae was first archaeologically explored by the German archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld in 1905, and in one excavation season in 1928, together with his assistant Friedrich Krefter.[11] Since 1946, the original documents, notebooks, photographs, fragments of wall paintings and pottery from the early excavations are preserved in the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, DC. After Herzfeld, Sir Aurel Stein completed a site plan for Pasargadae in 1934.[12] In 1935, Erich F. Schmidt produced a series of aerial photographs of the entire complex.[13]

From 1949 to 1955, an Iranian team led by Ali Sami worked there.[14] A British Institute of Persian Studies team led by David Stronach resumed excavation from 1961 to 1963.[15][16][17] It was during the 1960s that a pot-hoard known as the Pasargadae Treasure was excavated near the foundations of 'Pavilion B' at the site. Dating to the 5th-4th centuries BC, the treasure consists of ornate Achaemenid jewellery made from gold and precious gems and is now housed in the National Museum of Iran and the British Museum.[18] It has been suggested that the treasure was buried as a subsequent action once Alexander the Great approached with his army, then remained buried, hinting at violence.[19]

After a gap, work was resumed by the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization and the Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée of the University of Lyon in 2000.[20][21] The complex is one of the key cultural heritage sites for tourism in Iran.[22]

Sivand Dam controversy

[edit]There has been growing concern regarding the proposed Sivand Dam, named after the nearby town of Sivand. Despite planning that has stretched over 10 years, Iran's own Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization was not aware of the broader areas of flooding during much of this time.

Its placement between both the ruins of Pasargadae and Persepolis has many archaeologists and Iranians worried that the dam will flood these UNESCO World Heritage sites, although scientists involved with the construction say this is not obvious because the sites sit above the planned waterline. Of the two sites, Pasargadae is the one considered to be more threatened. Experts agree that the planning of future dam projects in Iran will merit an earlier examination of the risks to cultural resource properties.[23]

Of broadly shared concern to archaeologists is the effect of the increase in humidity caused by the lake.[24] All agree that the humidity created by it will speed up the destruction of Pasargadae, yet experts from the Ministry of Energy believe it could be partially compensated for by controlling the water level of the reservoir.

Construction of the dam began on 19 April 2007, with the height of the waterline limited so as to mitigate damage to the ruins.[25]

In popular culture

[edit]

In 1930, the Brazilian poet Manuel Bandeira published a poem called "Vou-me embora pra Pasárgada" ("I'm off to Pasargadae" in Portuguese), in a book entitled Libertinagem.[26] It tells the story of a man who wants to go to Pasargadae, described in the poem as a utopian city, having the children learned in the school about this "utopic city created by Manuel Bandeira". Manuel Bandeira heard the name Pasargadae for the first time when he was 16 years old, reading a book by a Greek author. The name of the field of the Persians reminded him of good things, of a place of tranquillity and beauties. Years later, in his apartment, during a moment of sadness and anxiety, he had the idea of “vou-me embora pra Pasárgada” (I'm off to Pasargadae) and then created the poem, which surrounds the great part of the Brazilian population’s imagination to this day.[27]

Gallery

[edit]-

Tomb of Cyrus the Great

-

Tomb of Cambyses I

-

The Private Palace.

-

The Audience Palace.

-

The Gateway Palace.

-

The citadel of Pasargadae. At its top many column bases indicate the structure was not unlike the Athenian Acropolis in positioning and structure.

-

Pasargad audience hall

-

Holy area (Pasargad)

-

Toll-e Takht hill (Pasargad)

-

Toll-e Takht hill (Pasargad)

-

The gate of the palace with the view of the winged man

-

The back of the 50 riyal banknote of the Pahlavi era

-

Pasargadae in 1920s

See also

[edit]- 2,500-year celebration of the Persian Empire

- Achaemenid architecture

- List of cities of the ancient Near East

- History of Iran

- Iranian architecture

- Tangeh Bolaghi

- Ka'ba-ye Zartosht, modeled after the "Prison of Solomon"

References

[edit]- ^ Gershevitch, Ilya, "Iranian Nouns and Names in Elamite Garb", Transactions of the Philological Society 68 (1), pp. 167–200, 1969 (1970)

- ^ Ancient Pasargadae threatened by construction of dam, Mehr News Agency, 28 August 2004, archived from the original on 11 March 2007, retrieved 15 September 2006.

- ^ "Pasargadae". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ Discovered Stone Slab Proved to be Gate of Cambyses' Tomb, CHN, archived from the original on 2009-11-29.

- ^ electricpulp.com. "PASARGADAE – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Arrian, Anabasis 6.29.8; de Sélincourt, Aubrey. "Arrian on the tomb of Cyrus - Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ Hogan, C Michael (Jan 19, 2008), "Tomb of Cyrus", The Megalithic Portal, Surrey, UK: Andy Burnham.

- ^ Ferrier, Ronald W (1989), The Arts of Persia, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-03987-0.

- ^ Lendering, Jona, Pasargadae, Livius, archived from the original on 2016-03-03, retrieved 2020-03-26.

- ^ Lynette Mitchell, A Persian King and his Garden, in Omnibus no 86 (2023), The Classical Association, Rickmansworth

- ^ Herzfeld, E (1929), Bericht über die Ausgrabungen von Pasargadae 1928 (in German), vol. 1, Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, pp. 4–16,

- ^ Stein, A (1936), An Archaeological Tour in Ancient Persis, Iraq, vol. 3, pp. 217–20.

- ^ Schmidt, Erich F (1940), Flights Over Ancient Cities of Iran (PDF), University of Chicago Oriental Institute, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-918986-96-2, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-09, retrieved 2011-06-22.

- ^ Ali-Sami (1971) [March 1956], Pasargadae. The Oldest Imperial. Capital of Iran, vol. 4, Rev. RN Sharp transl (2nd ed.), Shiraz: Learned Society of Pars; Musavi Print. Office.

- ^ Stronach, David (1963), "First Preliminary Report", Excavations at Pasargadae, Iran, vol. 1, pp. 19–42.

- ^ ———————— (1964), "Second Preliminary Report", Excavations at Pasargadae, Iran, vol. 2, pp. 21–39.

- ^ ———————— (1965), "Third Preliminary Report", Excavations at Pasargadae, Iran, vol. 3, pp. 9–40.

- ^ "Collection search: You searched for Pasargadae Pavilion B Hoard". British Museum. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ "Pasargadae, Paradise". Livius.

- ^ Boucharlat, Rémy (2002), Pasargadae, Iran, vol. 40, pp. 279–82.

- ^ [1] Sébastien Gondet et al, Field Report on the 2015 Current Archaeological Works of the Joint Iran-French Project on Pasargadae and its Territory, International Journal of Iranian Heritage Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 60-87, 2018

- ^ Butler, Richard; O'Gorman, Kevin D.; Prentice, Richard (2012-07-01). "Destination Appraisal for European Cultural Tourism to Iran". International Journal of Tourism Research. 14 (4): 323–338. doi:10.1002/jtr.862. ISSN 1522-1970.

- ^ Sivand Dam Waits for Excavations to be Finished, Cultural Heritage News Agency, 26 February 2006, archived from the original on 11 March 2007, retrieved Sep 15, 2006.

- ^ Date of Sivand Dam Inundation Not Yet Agreed Upon, Cultural Heritage News Agency, 29 May 2006, archived from the original on 12 March 2007, retrieved Sep 15, 2006.

- ^ "Lamentable Loss". 22 June 2015.

- ^ Bandeira, Manuel (2009). "Libertinagem" [Salacity]. In Seffrin, André (organizer) (ed.). Manuel Bandeira: poesia completa e prosa, volume único [Manuel Bandeira: complete poetry and prose, unique volume] (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro [(City) "River of January"], RJ [(State) "River of January"], Brasil [Brazil]: Editora Nova Aguilar [New Aguilar Press]. pp. XXIII, 118–119.

- ^ "We came back from Pasargadae – Monday Feelings". 2015-10-04. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

Bibliography

[edit]- Sivand Dam's Inundation Postponed for 6 Months, Cultural Heritage News Agency, 29 November 2005, archived from the original on 12 March 2007, retrieved Sep 15, 2006.

- Fathi, Nazila (November 27, 2005), "A Rush to Excavate Ancient Iranian Sites", The New York Times; fully accessible at Fathi, Nazila (27 November 2005), "SF Gate", The San Francisco Chronicle.

- Ali Mousavi (September 16, 2005), "Cyrus can rest in peace: Pasargadae and rumors about the dangers of Sivand Dam", History, Iranian, archived from the original on May 23, 2010.

- Pasargadae Will Never Drown, Cultural Heritage News Agency, 12 September 2005, archived from the original on 12 March 2007, retrieved Sep 15, 2006.

- Matheson, Sylvia A, Persia: An Archaeological Guide.

- Seffrin, André (2009), Manuel Bandeira: poesia completa e prosa, volume único [Manuel Bandeira: complete poetry and prose, unique volume], Rio de Janeiro: Editora Nova Aguilar, ISBN 978-85-210-0108-9.

- Stronach, David (1978), Pasargadae: A Report on the Excavations Conducted by the British Institute of Persian Studies from 1961–63, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-813190-8.

- Ali Mozaffari, World Heritage in Iran: Perspectives on Pasargadae, Routledge, 2016, ISBN 978-1409448440

External links

[edit]- Excavation Documentation and Fragments of Wall Paintings from Pasargadae

- World Heritage Center, Unesco.

- "Pasargadae", History, Iran Chamber Society.

- "Pasargad", Land of Aryan, ATSpace.

- Pasargad (virtual reconstruction of Pasargadae), Persepolis3D.

- Persepolis & Pasargad (in German), M Heße, 2009, archived from the original (photo gallery) on 2016-04-20, retrieved 2009-04-11.

- Pasargadae - Livius

- Pasargadae, Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran, archived from the original on 2011-10-20

- Populated places established in the 6th century BC

- Buildings and structures completed in the 6th century BC

- Archaeological sites in Iran

- World Heritage Sites in Iran

- Architecture in Iran

- Persian gardens in Iran

- Achaemenid cities

- Archaeology of the Achaemenid Empire

- Former populated places in Iran

- Buildings and structures in Fars province

- Collection of the Smithsonian Institution

- Cyrus the Great

- Tourist attractions in Fars province

- National works of Iran