Chatham Borough, New Jersey

Chatham Borough, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

Main Street in Downtown Chatham | |

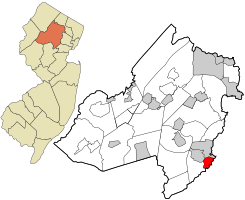

Location of Chatham (borough) in Morris County highlighted in red (right). Inset map: Location of Morris County in New Jersey highlighted in orange (left). | |

Census Bureau map of Chatham (borough), New Jersey | |

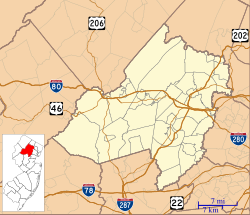

Location in Morris County | |

| Coordinates: 40°44′26″N 74°23′04″W / 40.740686°N 74.38448°W[1][2] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| European settlement | 1710 (as a colonial village) |

| Incorporated | August 19, 1892 (as village) |

| Reincorporated | March 1, 1897 (as borough) |

| Named for | William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham |

| Government | |

| • Type | Borough |

| • Body | Borough Council |

| • Mayor | Carolyn Dempsey (D, term ends December 31, 2027)[3][4] |

| • Administrator | Steven W. Williams[5] |

| • Municipal clerk | Vanessa Nienhouse[6] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.38 sq mi (6.16 km2) |

| • Land | 2.34 sq mi (6.07 km2) |

| • Water | 0.04 sq mi (0.09 km2) 1.51% |

| • Rank | 382nd of 565 in state 32nd of 39 in county[1] |

| Elevation | 233 ft (71 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 9,212 |

| • Estimate | 9,275 |

| • Rank | 257th of 565 in state 21st of 39 in county[13] |

| • Density | 3,925.0/sq mi (1,515.5/km2) |

| • Rank | 167th of 565 in state 7th of 39 in county[13] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (Eastern (EDT)) |

| ZIP Code | |

| Area code(s) | 973[16] |

| FIPS code | 34-12100[1][17][18] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0885182[1][19] |

| Website | www |

Chatham Borough is a suburban borough in Morris County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 United States census, the borough's population was 9,212,[10][11] an increase of 250 (+2.8%) from the 2010 census count of 8,962,[20][21] which in turn reflected an increase of 502 (+5.9%) from the 8,460 counted in the 2000 census.[22]

The area that is now Chatham has been inhabited by humans for thousands of years. During historic times, Europeans began trading with the Native Americans who farmed, fished, and hunted in the area when it was claimed as part of New Netherlands. The community that now is Chatham was first settled by Europeans in 1710 within Morris Township, in what was then the English Province of New Jersey. The community was settled because the site already was on the path of a well-worn Native American trail, the location of an important crossing of the Passaic River, and being close to a gap in the Watchung Mountains. The residents of the English community changed its name from John Day's Bridge to Chatham, New Jersey in 1773.[23]

Chatham's residents were active participants in the American Revolutionary War, which ended in 1783. Chatham Township was formed as a local government in the new state of New Jersey on February 12, 1806, taking its name from this pre-revolutionary village. Initial local government forms were limited while the new state government evolved. The new township governed the village of Chatham that lay within the present-day borough boundaries, along with several other pre-revolutionary, colonial villages and large areas of unsettled lands connecting or adjacent to them. On August 19, 1892, Chatham adopted a new village form of government when it became allowed within townships in the state after the revolution. Shortly thereafter, once it was allowed, the village of Chatham reincorporated for governance as a borough by an act of the New Jersey Legislature on March 1, 1897, returning to complete independence from the surrounding Chatham Township.[24][25]

An early railroad located along the Morris and Essex Lines that had become well established by the start of the Civil War as one of America's first commuter railroads, had a stop at Chatham, which attracted many from nearby Manhattan, 20 miles to the east.[26] It remains a commuter town for residents who work in New York City. Today, Chatham is a pedestrian-friendly community that covers less than 2.5 square miles (6.5 km2), including a central business district and railroad station within approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) from its farthest boundary. The borough is situated in southeastern Morris County bordering both Essex and Union counties along the Passaic River. Northeast of the borough is the upscale Mall at Short Hills located in the Short Hills section of Millburn.

In July 2005, CNN/Money and Money magazine ranked Chatham ninth on its annual list of the 100 Best Places to Live in the United States.[27] New Jersey Monthly magazine ranked Chatham as its 25th best place to live in its 2008 rankings of the "Best Places To Live" in New Jersey.[28] In 2012, Forbes.com listed Chatham as 375th in its listing of "America's Most Expensive ZIP Codes", with a median home price of $776,703.[29]

The borough has been ranked as one of the state's highest-income communities. In March 2018, Bloomberg ranked Chatham as the 64th highest-income place in the United States and as having the 8th-highest income in New Jersey.[30] In the 2013–2017 American Community Survey (ACS) the borough had a median household income of $163,026, ranking 16th in the state.[31][32] The 2014–2018 ACS showed a median household income of $169,524 in the borough versus $111,316 in the county and $79,363 statewide.[33][34][35] The most-recent (2021) ACS places the median household income of Chatham Borough at $209,283.[36]

History[edit]

Occupied for thousands of years by Native Americans, this land was overseen by clans of the Minsi and Lenni Lenape, who farmed, fished, and hunted upon it. They were organized into a matrilineal, agricultural, and mobile hunting society sustained with fixed, but not permanent, settlements in their clan territories. Villages were established and relocated as the clans farmed new sections of the land when soil fertility lessened and moved among their fishing and hunting grounds.

In 1498, John Cabot explored this portion of the New World. The area was claimed as a part of the Dutch New Netherland province, where active trading in furs took advantage of the natural pass west, but, the Lenape prevented permanent settlement beyond what is now Jersey City. Although rapid exhaustion of the local beaver population soon turned the Dutch interests much farther north, contention existed between the Dutch and the British over the rights to this land and battles ensued. Passing to the rule of the British as the Province of New Jersey upon the fall of New Amsterdam in 1664, and becoming one of its original thirteen colonies, marks the beginning of permanent European settlements on this land.

The land that would become Chatham was part of the Province of East Jersey; the Indian rights to Chatham were purchased in 1680 from members of the Minsi and Lenni Lenape tribes. They spoke an Algonquian language. They hunted and fished in the area and farmed on the lands of their settlements. The area was well connected with established paths among their settlements, to and from bountiful resources, and to neighboring settlements. Safe passageways through the valleys, marshes, swamps, and mountains of this portion of the Watchung Mountains connected the area that would become Chatham with other settlements in the area. Except for highways built since the 1970s and a shunpike built to avoid tolls on the roads connecting the colonial settlements of Chatham and Bottle Hill, the roads of the area follow those time proven, long trodden trails made by the native tribes. Main Street rises from a shallow crossing of the Passaic River and, after traveling through what became the settlements of Chatham and Bottle Hill (which became Madison), the road follows a westward path that leads to the top of the plateau on which Morristown was founded.

In 1680, the British first purchased this Lenape land upon which John Day made the first European settlement in 1710. He chose to settle upon the western bank of the Fishawack Crossing (of the Passaic River) on the traditional Lenape Minisink Trail. Chatham was in the area delineated as Morris Township by the English. The landing at that location was the best place to ford the river and always had been used by the Lenape on their route to the Hudson River and south from their hunting grounds in what is now Sussex County. That traditional part of the Great Trail would become today’s Route 124, leading to Madison, Morristown, Mendham, and Chester. It became known as Main Street in Chatham.

Before long, the village became known as John Day's Bridge because of a bridge he built across the river at the shallow landing. By 1750, the village had a blacksmith shop as well as a flour mill, a grist mill, and a lumber mill.

In 1773, the village was renamed to "Chatham" to honor a member of the British Parliament, William Pitt, the first Earl of Chatham, who was an outspoken advocate of the rights of the colonists in America.[23][37][38]

New Jersey was one of the Thirteen Colonies that revolted against British rule in the American Revolutionary War. The New Jersey Constitution of 1776 was passed on July 2, 1776, two days before the Second Continental Congress declared American Independence from Great Britain. It was an act of the New Jersey Provincial Congress, which made itself into the state legislature. To reassure neutrals, it provided that it would become void if the state of New Jersey reached reconciliation with Great Britain.

The citizens of Chatham were active participants in the Revolutionary War and nearby Morristown became the military center of the revolution. George Washington twice established his winter headquarters in Morristown and revolutionary troops were active regularly in the entire area. The Lenape assisted the colonists, supplying the revolutionary army with warriors and scouts in exchange for food supplies and the promise of a role at the head of a future Native American state. The Treaty of Easton signed by the Lenape and the British in 1766 had required that the Lenape move to Pennsylvania. Wanting to recoup rights lost thereby to the British, the Lenape were the first tribe to enter into a treaty with the emerging government of the United States.[39] In 1781, General Rochambeau built a large bakery operation at Chatham as a subterfuge that could be interpreted as his plan to stay in Chatham for an extended amount of time, in order to distract from the fact that his troops were marching south toward Yorktown.[40]

The Watchung mountain range was a strategic asset in the war, acting as a natural barrier to the British troops and providing a vantage point for Washington to monitor their troop movements. The Minisink Trail and the village bridge provided a route for essential supplies across the river and through the mountain range. The Hobart Gap was vital as the only pass through the Watchung Mountains.[41]

Washington wrote 17 letters while he stayed at a homestead in Chatham. The community was the site of several skirmishes, as residents and the rebel army held off British advances, preventing them from attacking Washington's supplies at Morristown.

In 1779, a printing press was established in the village of Chatham by Shepard Kollock. From his workshop, he published books,[42] pamphlets, and the New Jersey Journal (the third newspaper published in New Jersey)[43] conducting lively debates about the efforts for independence and boosting the morale of the troops and their families with information derived directly from Washington's headquarters in nearby Morristown. Kollock's newspaper was published until 1992 as the Elizabeth Daily Journal (having relocated to there in 1787) and was the fourth oldest newspaper published continuously in the United States.[44]

After the Revolutionary War was over in 1783, establishment of new forms of government began. On February 12, 1806, the village of Chatham became part of Chatham Township with a township form of government that shared the village's name and included several other area communities and a large amount of unsettled land. However, "[i]n 1892 Chatham Village found itself at odds with the rest of the township. Although village residents paid 40 percent of the township taxes, they got only 7 percent of the receipts in services. The village had to raise its own money to install kerosene street lamps and its roads were in poor repair. As a result, the village voted on August 9, 1892, to secede from governance by the township."[23]

Ten days later, on August 19, 1892, the citizens of Chatham reincorporated with another type of village government then offered as an alternative within townships by the new state. The evolving state regulations regarding governance structure soon began to offer a borough form for governance. Chatham adopted that new government form and the village reincorporated for governance as a borough by an act of the New Jersey Legislature on March 1, 1897, with complete independence from Chatham Township.[24]

Most of the colonial settlements that had been part of Chatham Township abandoned its governance as soon as new forms of government became available to them during this evolution of new state regulations. Green Village being the exception, each of the settlements withdrew from governance by the township and Chatham Township was left to govern mostly unsettled lands.

In 1910, the borough boundaries expanded when Chatham acquired a slice of Florham Park.[24] The local form of government and the boundaries of the borough have remained the same since that acquisition, encompassing about 2.4 square miles (6.2 km2).

Architecture[edit]

At 2.4 square miles (6.2 km2) in area, Chatham was mostly built out well before World War II, retaining homes that sometimes display the dates of their construction during the colonial and revolutionary times. Two houses, now privately owned, survive from colonial times; the Paul Day House, at 24 Kings Road, and the Nathaniel Bonnell House, at 34 Watchung Avenue.[23]

Geography[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the borough had a total area of 2.38 square miles (6.17 km2), including 2.35 square miles (6.08 km2) of land and 0.04 square miles (0.09 km2) of water (1.51%).[1][2][1][2]

Unincorporated communities, localities and place names located partially or completely within the borough include Stanley.[45]

The borough is located 20 miles (32 km) west of New York City on the eastern edge of Morris County. Chatham's neighboring communities are Summit to the southeast located in Union County, Millburn (and its Short Hills neighborhood) in Essex County to the northeast, while communities also located in Morris County include Chatham Township to the west, and Madison and Florham Park to the north.[46][47][48]

The Passaic River, which rises at Millington Gorge in Long Hill Township and defines the Great Swamp, flows north along the eastern boundary of Chatham.[49] A good crossing location, identified by Native Americans to early European settlers, figured significantly in the colonial history of the community. Fairmount Avenue ascends Long Hill perpendicularly from Main Street in the contemporary center of town to the highest elevation of the town among the Watchung Mountains. From there, one may see the lights of New York beyond the crest of the ridge hills of Summit and Short Hills. Water from artesian wells is stored at its crest to provide the drinking water for the community.

A portion of the Great Swamp extends to the southern boundary of Chatham and other marshes surround the community to the north and northwest. The marshes and brooks in the area contain water draining from the plateau of Morristown and many points to the north and west. All are remnants of a massive lake that covered the area following the retreat of the Wisconsin glacier of the last Ice age. Residents of Chatham were among those in late 1959 who formed the Jersey Jetport Site Association and instigated preservation of the Great Swamp when the New York Port Authority sought to turn it into a massive regional airport.[50][51][52] They later were joined by the North American Wildlife Foundation that completed acquisition of enough of the Great Swamp to protect the massive natural resource as a federal park.

The Great Swamp is a major watershed and a significant resting point for migratory birds. The core of the swamp was purchased with the help of Geraldine R. Dodge and Marcellus Hartley Dodge Sr. Several other members of the Jersey Jetport Site Association, including two residents of Chatham, Kafi Benz and Esty Weiss, who were students at the nearby campus of Fairleigh Dickinson University, began to infiltrate meetings of the administration of Austin Joseph Tobin, the executive director of the Port Authority. They attended meetings scheduled quietly to garner the support of union workers. Once inside the meetings, they provided pamphlets in opposition to the project, which infuriated the Port Authority administration. Eventually, other organizations formed to join the opposition to the plans for the airport and finally, a majority of the swamp was assembled to be donated to the federal government to become a National Wildlife Refuge. Stewart Udall, Secretary of the Interior under President John F. Kennedy, lent his support to the local efforts to save the swamp while he served as U.S. Representative from Arizona, making recommendations to the Dwight D. Eisenhower administration to also lend their support. On November 3, 1960, the legislation creating the Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge was passed by an act of the United States Congress.[53][54]

Just northeast of the borough is the upscale Mall at Short Hills located in the Short Hills section of Millburn.

Climate[edit]

Chatham has a humid continental climate and is slightly more variant (lows are colder, highs are warmer) than its neighbor 20 miles (32 km) east: New York City.

| Climate data for Chatham (07928, includes Chatham (borough) and Chatham Township) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 73 (23) |

82 (28) |

89 (32) |

96 (36) |

97 (36) |

103 (39) |

107 (42) |

104 (40) |

99 (37) |

93 (34) |

84 (29) |

76 (24) |

107 (42) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 39 (4) |

42 (6) |

51 (11) |

62 (17) |

73 (23) |

82 (28) |

86 (30) |

85 (29) |

78 (26) |

66 (19) |

55 (13) |

44 (7) |

64 (18) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 18 (−8) |

20 (−7) |

28 (−2) |

38 (3) |

47 (8) |

57 (14) |

63 (17) |

61 (16) |

53 (12) |

40 (4) |

32 (0) |

24 (−4) |

40 (4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −25 (−32) |

−26 (−32) |

−6 (−21) |

12 (−11) |

25 (−4) |

31 (−1) |

41 (5) |

35 (2) |

26 (−3) |

13 (−11) |

−5 (−21) |

— | −26 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.54 (90) |

2.91 (74) |

4.20 (107) |

4.29 (109) |

4.38 (111) |

4.70 (119) |

4.73 (120) |

4.42 (112) |

4.89 (124) |

4.65 (118) |

4.06 (103) |

4.13 (105) |

50.90 (1,293) |

| Source: [55] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 738 | — | |

| 1890 | 780 | 5.7% | |

| 1900 | 1,361 | 74.5% | |

| 1910 | 1,874 | 37.7% | |

| 1920 | 2,421 | 29.2% | |

| 1930 | 3,869 | 59.8% | |

| 1940 | 4,888 | 26.3% | |

| 1950 | 7,391 | 51.2% | |

| 1960 | 9,517 | 28.8% | |

| 1970 | 9,566 | 0.5% | |

| 1980 | 8,537 | −10.8% | |

| 1990 | 8,007 | −6.2% | |

| 2000 | 8,460 | 5.7% | |

| 2010 | 8,962 | 5.9% | |

| 2020 | 9,212 | 2.8% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 9,275 | [10][12] | 0.7% |

| Population sources: 1880–1890[56] 1890–1920[57] 1890–1910[58] 1910–1930[59] 1940–2000[60] 2000[61][62] 2010[20][21] 2020[10][11] | |||

2010 census[edit]

The 2010 United States census counted 8,962 people, 3,073 households, and 2,397 families in the borough. The population density was 3,776.1 per square mile (1,458.0/km2). There were 3,210 housing units at an average density of 1,352.5 per square mile (522.2/km2). The racial makeup was 91.13% (8,167) White, 0.99% (89) Black or African American, 0.20% (18) Native American, 4.85% (435) Asian, 0.00% (0) Pacific Islander, 1.00% (90) from other races, and 1.82% (163) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.10% (457) of the population.[20]

Of the 3,073 households, 48.1% had children under the age of 18; 68.9% were married couples living together; 7.0% had a female householder with no husband present and 22.0% were non-families. Of all households, 18.6% were made up of individuals and 7.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.91 and the average family size was 3.37.[20]

33.5% of the population were under the age of 18, 3.9% from 18 to 24, 25.8% from 25 to 44, 26.7% from 45 to 64, and 10.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38.0 years. For every 100 females, the population had 94.1 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 89.9 males.[20]

The Census Bureau's 2006–2010 American Community Survey showed that (in 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars) median household income was $143,281 (with a margin of error of +/− $14,294) and the median family income was $164,805 (+/− $12,245). Males had a median income of $127,906 (+/− $13,208) versus $59,271 (+/− $14,990) for females. The per capita income for the borough was $64,950 (+/− $5,936). About 0.4% of families and 1.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 0.3% of those under age 18 and 7.5% of those age 65 or over.[63]

Based on data from the 2006–2010 American Community Survey, the borough had a per capita income of $64,950 (ranked 37th in the state), compared to per capita income in Morris County of $47,342 and statewide of $34,858.[64]

2000 census[edit]

As of the 2000 United States census[17] there were 8,460 people, 3,159 households, and 2,385 families. The population density was 3,505.9 inhabitants per square mile (1,353.6/km2). There were 3,232 housing units at an average density of 1,339.4 per square mile (517.1/km2). The racial makeup of was 95.79% White, 0.14% African American, 0.06% Native American, 2.81% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 0.50% from other races, and 0.69% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.64% of the population.[61][62]

There were 3,159 households, out of which 39.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 67.6% were married couples living together, 6.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 24.5% were non-families. 21.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.67 and the average family size was 3.14.[61][62]

The population was spread out, with 28.3% under the age of 18, 3.8% from 18 to 24, 33.5% from 25 to 44, 21.4% from 45 to 64, and 13.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.0 males.[61][62]

The median income for a household was $101,991, and the median income for a family was $119,635. Males had a median income of $81,543 versus $59,063 for females. The per capita income was $53,027. About 1.7% of families and 2.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 1.0% of those under age 18 and 3.3% of those age 65 or over.[61][62]

Economy[edit]

Now headquartered in Morris Plains, Weichert, Realtors was established by Jim Weichert in 1969 with an office in Chatham Borough.[65] The borough is home to Chatham Asset Management, a hedge fund holding a controlling interest in several large media companies.

Government[edit]

From 1614, the area was governed by the Dutch as part of New Netherland. In 1664, it came under governance by the British within the Province of New Jersey, during which a permanent European settlement was established in 1710 that changed its name to Chatham in 1773.

Chatham has adopted different forms of local government throughout its existence. Under British colonial rule, a village form of government was adopted. After the American Revolutionary War, the community became part of Chatham Township, which was founded by new state of New Jersey in 1806 as it was beginning to determine governmental forms. That township also included several other settlements and a great deal of unsettled lands. Unhappy with that governance, Chatham seceded from the township in 1892 and returned to a village government. When the borough form of government was offered by the state, Chatham adopted that form of government by a reincorporation in 1897, and that governmental form has been used ever since.[24]

Local government[edit]

Having adopted several different forms of government since its settlement in 1710, Chatham adopted the newly allowed borough form of New Jersey municipal government during a reincorporation in 1897. The borough form of government is now used in 218 municipalities (of the 564) statewide, making it the most common form of government in New Jersey.[66] The governing body is comprised of the mayor and the borough council, with all positions elected at-large on a partisan basis as part of the November general election. A mayor is elected directly by the voters to a four-year term of office. The borough council includes six members elected to serve three-year terms on a staggered basis, with two seats coming up for election each year in a three-year cycle.[7] The borough form of government used by Chatham is a "weak mayor / strong council" government in which council members act as the legislative body with the mayor presiding at meetings and voting only in the event of a tie. The mayor can veto ordinances subject to an override by a two-thirds majority vote of the council. The mayor makes committee and liaison assignments for council members, and most appointments are made by the mayor with the advice and consent of the council.[67][68]

As of 2024[update], the Mayor is Democrat Carolyn Dempsey, whose term of office ends December 31, 2027. Members of the borough council are Council President Jocelyn Mathiasen (D, 2024), Brian Hargrove (D, 2026), Katherine Hay (D, 2024), Karen Koronkiewicz (D, 2025), Justin Strickland (D, 2026) and Irene Treloar (D, 2025).[3][69][70][71][72][73][74]

Federal, state, and county representation[edit]

The borough is located in the 11th Congressional District[75] and is part of the 21st state legislative district of New Jersey.[76][77][78]

For the 118th United States Congress, New Jersey's 11th congressional district is represented by Mikie Sherrill (D, Montclair).[79] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2027)[80] and Bob Menendez (Englewood Cliffs, term ends 2025).[81][82]

For the 2024-2025 session, the 21st legislative district of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Jon Bramnick (R, Westfield) and in the General Assembly by Michele Matsikoudis (R, New Providence) and Nancy Munoz (R, Summit).[83]

Morris County is governed by a Board of County Commissioners composed of seven members who are elected at-large in partisan elections to three-year terms on a staggered basis, with either one or three seats up for election each year as part of the November general election.[84] Actual day-to-day operation of departments is supervised by County Administrator Deena Leary.[85]: 8 As of 2024[update], Morris County's Commissioners are:

John Krickus (R, Chatham Township, 2024),[86] Director Christine Myers (R, Harding, 2025),[87] Douglas Cabana (R, Boonton Township, 2025),[88] Thomas J. Mastrangelo (R, Montville, 2025),[89] Deputy Director Stephen H. Shaw (R, Mountain Lakes, 2024),[90] Deborah Smith (R, Denville, 2024)[91] and Tayfun Selen (R, Chatham Township, 2026)[85]: 2 [92]

The county's constitutional officers are: Clerk Ann F. Grossi (R, Parsippany–Troy Hills, 2028),[93][94] Sheriff James M. Gannon (R, Boonton Township, 2025)[95][96] and Surrogate Heather Darling (R, Roxbury, 2024).[97][98]

Politics[edit]

As of March 2011, there were a total of 5,750 registered voters in the borough, of which 1,368 (23.8%) were registered as Democrats, 1,928 (33.5%) were registered as Republicans and 2,452 (42.6%) were registered as Unaffiliated. There were two voters registered as either Libertarian or Green.[99]

In the 2012 presidential election, Republican Mitt Romney received 54.6% of the vote (2,501 cast), ahead of Democrat Barack Obama with 44.7% (2,045 votes), and other candidates with 0.7% (33 votes), among the 4,600 ballots cast by the borough's 6,131 registered voters (21 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 75.0%.[100][101] In the 2008 presidential election, Republican John McCain received 50.2% of the vote (2,413 cast), ahead of Democrat Barack Obama with 48.4% (2,325 votes) and other candidates with 0.9% (44 votes), among the 4,807 ballots cast by the borough's 5,975 registered voters, for a turnout of 80.5%.[102] In the 2004 presidential election, Republican George W. Bush received 56.7% of the vote (2,678 ballots cast), outpolling Democrat John Kerry with 42.3% (1,995 votes) and other candidates with 0.5% (28 votes), among the 4,721 ballots cast by the borough's 6,084 registered voters, for a turnout percentage of 77.6.[103]

In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Republican Chris Christie received 71.1% of the vote (1,770 cast), ahead of Democrat Barbara Buono with 27.2% (678 votes), and other candidates with 1.6% (41 votes), among the 2,530 ballots cast by the borough's 6,046 registered voters (41 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 41.8%.[104][105] In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Republican Chris Christie received 56.6% of the vote (1,892 ballots cast), ahead of Democrat Jon Corzine with 32.7% (1,092 votes), Independent Chris Daggett with 9.7% (325 votes) and other candidates with 0.4% (14 votes), among the 3,344 ballots cast by the borough's 5,831 registered voters, yielding a 57.3% turnout.[106]

[edit]

The borough shares various joint public services with Chatham Township: the recreation program, the library (since 1974), the school district (created in 1986), and medical emergency squad (since 1936).

Along with Chatham Township, Harding Township, and Madison, the borough became a member of a joint municipal court that was created in 2010.[107][108] The court is located in Madison.

Fishawack Festival[edit]

First celebrated in 1971, the Fishawack Festival is held in the beginning of summer, on South Passaic Avenue and Fire House Plaza, which are blocked off so up to 20,000 attendees may walk freely in the streets. Local vendors set up booths to sell food, clothing, toys, and various other souvenirs, as well as offering games and rides for children. The festival has been sponsored by the Madison YMCA, PipeWorks Services, and Klas Electrical. Funds generated from the Fishawack Festival go toward various community groups located in Chatham and Chatham Township.

The word "Fishawack" is derived from the Lenni Lenape name for the Passaic River. In a book about the derivation of the name for the festival, Chatham at the Crossing of the Fishawack by John T. Cunningham, the author noted, "Fishawack was the Lenni Lenape Indian name for the Passaic River and Chatham was located at the narrowest part making it the Crossing of the Fishawack in the Valley of the Great Watchung... In 1971, a Chamber of Commerce sidewalk sale day, called Fishawack Day, was held. Thus began an event, which in time was adopted by Fishawack Inc., the governing body of volunteers who turned it into a big biennial town-wide Festival.".[109]

Education[edit]

Public schools[edit]

The School District of the Chathams is a regional public school district serving students in pre-kindergarten through twelfth grade from Chatham and Chatham Township.[110] The two municipalities held elections in November 1986 to consider joining their separate school districts. This proposal was supported by the voters of both communities and since then, the two municipalities have shared a regionalized school district.[111][112] Starting with the 1988–1989 school year, Chatham High School was formed by merging the former Chatham Borough High School and Chatham Township High School facilities. The Chatham Borough High School building was repurposed as the Chatham Borough Hall.[113]

As of the 2020–21 school year, the district, comprised of six schools, had an enrollment of 3,930 students and 342.8 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 11.5:1.[114] Schools in the district (with 2020–21 enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics[115]) are Milton Avenue School[116] with 284 students in grades Pre-K–3, Southern Boulevard School[117] with 414 students in grades K–3, Washington Avenue School[118] with 314 students in grades K–3, Lafayette School[119] with 592 students in grades 4–5, Chatham Middle School[120] with 984 students in grades 6–8 and Chatham High School[121] with 1,315 students in grades 9–12.[122][123] The district board of education has nine members who set policy and oversee the fiscal and educational operation of the district through its administration; the seats on the board are allocated to the constituent municipalities based on population, with the borough assigned four seats.[124]

For the 2004–2005 school year, Chatham High School was recognized with the National Blue Ribbon School Award of Excellence by the United States Department of Education,[125] the highest award an American school can receive. Milton Avenue School was one of 11 in the state to be recognized in 2014 by the United States Department of Education's National Blue Ribbon Schools Program.[126][127] The district high school was the first-ranked public high school in New Jersey out of 339 schools statewide in New Jersey Monthly magazine's September 2014 cover story on the state's "Top Public High Schools", using a new ranking methodology.[128] The school had been ranked twentieth in the state of 328 schools in 2012, after being ranked eighth in 2010 out of 322 schools listed.[129]

Private schools[edit]

Saint Patrick School, founded in 1872, serves students in pre-kindergarten through eighth grade, operating under the direction of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Paterson.[130]

Transportation[edit]

Roads and highways[edit]

As of May 2010[update], the borough had a total of 32.16 miles (51.76 km) of roadways, of which 26.56 miles (42.74 km) were maintained by the municipality, 3.33 miles (5.36 km) by Morris County and 2.27 miles (3.65 km) by the New Jersey Department of Transportation.[131]

New Jersey Route 24 is a multi-lane state freeway crossing the borough boundaries, though the nearest interchange is just outside the borough along the boundary of Summit and Millburn. New Jersey Route 124 is the main local road providing access to Chatham along the route that connected the area before the limited access highway was built. This local route wound its way through the area since before colonial times following the course of the Great Minisink Trail and had been designated as Route 24 until it was renumbered to Route 124 when the limited access highway was built in the late 1900s. The local communities chose to retain their historic character and opted out of plans for the multi-lane, limited access highway. The nearest interchanges with the new Route 24 are in neighboring communities, to the east it is Millburn and to the west it is Hanover Township.

In 1906, the borough received coverage from The New York Times and The Chatham Press for implementation of what may be the world's first recorded use of a speed bump as a traffic calming device.[132] A report from the April 24, 1906, issue of The Times described how "[t]he 'bumps' installed by the borough officials of the village of Chatham to check the speed of automobiles through the village had their first test yesterday, and proved a decided success."[133]

Public transportation[edit]

NJ Transit stops at the Chatham station[134] to provide commuter service on the Morristown Line, with trains heading to the Hoboken Terminal and to Penn Station in Midtown Manhattan.[135]

Direct bus service from Chatham to Manhattan is not provided by NJ Transit. It provides various route options with bus transfers. Local bus service is provided by NJ Transit on the 873 route to the Livingston Mall and Parsippany-Troy Hills,[136][137] which replaced service that had been offered until 2010 on the MCM3 and MCM8 routes.[138]

Bus lines also connect Chatham with the other towns along Route 24 from Newark to Morristown, mostly running parallel to the train lines. Nowadays, buses transport people along the line, but stagecoaches and trolleys were mass transit methods once used along the route that followed Main Street. That section of the old route now is labeled Route 124 because of the opening of a new Route 24, a modern highway. The destruction of the historic downtown by a proposed widening of the historic route was opposed and after much debate, an alternate route was chosen to preserve the historic character of downtown Chatham and downtown Madison. The last rails for the trolley system were removed from the area roads in the 1950s.[citation needed]

Library[edit]

Chatham Library was founded in 1907 in downtown Chatham after decades of discussion and planning. Growth of the collection brought about expansion and movement to progressively larger facilities until the current building was built on Main Street on the former site of the Fairview Hotel, after it had burned down. The hotel land was bought after a borough-wide solicitation of funds that was proposed by Charles M. Lum, after whose family Lum Avenue is named, and a brick building was constructed to house the library. The new Chatham Library was dedicated and opened to the public in 1924.[139]

A referendum on the November 1974 ballot regarding jointure was approved by voters, providing that the Chatham Library also would serve Chatham Township residents. The library was renamed as the Library of The Chathams, which now is administered by six trustees, who are appointed jointly through the two governments via the mayors of the two municipalities or their representatives, as well as a representative from the newly created joint School District of the Chathams.[139]

In 1985, the library joined the Morris Automated Information Network (MAIN), an electronic database created to link together all of the public libraries in Morris County. Expansion of the library with an addition costing nearly $4,000,000 was planned with the governments of the two municipalities contributing a combined $2,000,000. The project was completed and the new addition dedicated on January 11, 2004.[139]

Sister city[edit]

Chatham has one sister city. It is ![]() Esternay, France.[140]

Esternay, France.[140]

Notable people[edit]

People who were born in, residents of, or otherwise closely associated with Chatham since its founding in 1710 include:

- Ben Bailey (born 1970), comedian and host of Discovery Channel's Cash Cab[141][142]

- Kafi Benz (born 1941), writer, artist, conservationist, and community leader[143]

- Leanna Brown (1935–2016), politician[144][145][146]

- Edward Everett Bruen (1859–1938), first mayor of East Orange, New Jersey, and a descendant of founders of Chatham[147][148]

- Bruce Harris (born 1951), attorney and politician who served as the borough mayor[149]

- Constance Horner (born 1942), businesswoman who served as the third director of the United States Office of Personnel Management[150]

- Shepard Kollock (1750–1839), American Revolutionary War-era editor, author, and printer of the New Jersey Journal, which became the first newspaper in Chatham and third newspaper in New Jersey in 1779[151]

- Ann McLaughlin Korologos (1941-2023, née Lauenstein), United States Secretary of Labor in the Reagan Administration[152]

- Nick Mangold (born 1984), American football center for the New York Jets of the National Football League[153]

- Joseph C. McDonough (1924-2005), decorated Major General in the United States Army[154]

- Bob Papa (born 1964), head radio announcer for the New York Giants[155]

- David K. Shipler (born 1942), author, correspondent, journalist, and filmmaker who won the 1987 Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction for Arab and Jew: Wounded Spirits in a Promised Land, won the George Polk Award, is the author of The Shipler Report, and is co-host of Two Reporters[156][157]

- Barbara Stanley (1949–2023), psychologist, researcher, and suicidologist[158]

- John Tolkin (born 2002), soccer defender for New York Red Bulls II in the USL Championship and the New York Red Bulls academy[159]

- Aaron Montgomery Ward (1844−1913), inventor of mail order and a descendant of colonial settlers[160]

- Alice Waters (born 1944), chef and pioneer of local, organic food movement[161]

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f 2019 Census Gazetteer Files: New Jersey Places, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mayor & Council, Borough of Chatham, Accessed May 5, 2024.

- ^ 2023 New Jersey Mayors Directory, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, updated February 8, 2023. Accessed February 10, 2023.

- ^ Administrator, Borough of Chatham. Accessed May 5, 2024.

- ^ Borough Clerk, Borough of Chatham. Accessed May 5, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b 2012 New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, March 2013, p. 121.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Borough of Chatham, Geographic Names Information System. Accessed March 5, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e QuickFacts Chatham borough, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed January 3, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Total Population: Census 2010 - Census 2020 New Jersey Municipalities, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Minor Civil Divisions in New Jersey: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023, United States Census Bureau, released May 2024. Accessed May 16, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Population Density by County and Municipality: New Jersey, 2020 and 2021, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Look Up a ZIP Code for Chatham, NJ, United States Postal Service. Accessed March 20, 2012.

- ^ ZIP Codes, State of New Jersey. Accessed October 8, 2013.

- ^ Area Code Lookup - NPA NXX for Chatham, NJ, Area-Codes.com. Accessed October 8, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b U.S. Census website, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ Geographic Codes Lookup for New Jersey, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- ^ US Board on Geographic Names, United States Geological Survey. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e DP-1 - Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 for Chatham borough, Morris County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010 for Chatham borough Archived March 22, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- ^ Table 7. Population for the Counties and Municipalities in New Jersey: 1990, 2000, and 2010, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, February 2011. Accessed May 1, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Cheslow, Jerry. "If You're Thinking of Living In/Chatham; Rich Past, Bustling but Homey Present", The New York Times, April 17, 1994. Accessed March 21, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Snyder, John P. The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606-1968, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 191. Accessed April 25, 2012.

- ^ Historical Timeline of Morris County Boundaries Archived December 25, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Morris County Library. Accessed December 24, 2016. "1897, March 1. Chatham Borough is established from Chatham Township."

- ^ "About Chatham".

- ^ MONEY Magazine – Best places to live 2005 – Chatham, NJ snapshot Archived May 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Best Places To Live - The Complete Top Towns List 1-100" Archived February 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Monthly, February 21, 2008. Accessed February 24, 2008.

- ^ Brennan, Morgan. "America's Most Expensive ZIP Codes 2012", Forbes, October 16, 2012. Accessed February 18, 2020.

- ^ Hagan, Shelly; and Lu, Wei. "America’s 100 Richest Places", Bloomberg News, March 5, 2018. Accessed February 19, 2020. "64 Chatham, N.J. Morris $223,219 (2016) $213,408 (2015)"

- ^ Cervenka, Susanne. "Rich in New Jersey: Here are the 50 wealthiest towns in the state. Is yours one of them?", Asbury Park Press, July 1, 2019. Accessed February 19, 2020. "16. Chatham Borough - County: Morris County; Median household income: $163,026

- ^ Chester Borough 2017 Census Data Summary, Morris County, New Jersey Office of Planning and Preservation. Accessed February 21, 2020.

- ^ QuickFacts for Chatham borough, New Jersey; Morris County, New Jersey; New Jersey from Population estimates, July 1, 2019, (V2019), United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- ^ Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Minor Civil Divisions in New Jersey: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019, United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- ^ Census Estimates for New Jersey April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019, United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- ^ Census Reporter: Chatham borough, New Jersey

- ^ Hutchinson, Viola L. The Origin of New Jersey Place Names, New Jersey Public Library Commission, May 1945. Accessed August 28, 2015.

- ^ Gannett, Henry. The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States, p. 77. United States Government Printing Office, 1905. Accessed August 28, 2015.

- ^ Treaty of 1778, America's First Indian Treaty, accessed December 31, 2006.

- ^ Selig, Robert A. The Washington - Rochambeau Revolutionary Route In The State Of New Jersey, 1781 - 1783 An Historical and Architectural Survey Volume I, New Jersey Historic Trust, 2006. Accessed July 12, 2020. "The establishment of large bakery operations could be interpreted as a sign that the army was going to stay in a given location for a while. In the context of the 1781, the bake ovens in Chatham, though necessary to feed the army on the march, also served an important function in the scheme of confirming in Clinton in the conviction that New York was the intended target of the campaign."

- ^ Why Morristown?, National Park Service. Accessed January 2, 2007. A blue arrow indicates American forces and a red arrow indicates British forces.

- ^ Shepard Kollock's Work[permanent dead link], accessed December 31, 2006.

- ^ Staff (May 8, 2009). "Eighteenth-Century American Newspapers in the Library of Congress (New Jersey)". Serial & Government Publications Division - Newspaper & Current Periodical Reading Room. Library of Congress. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Staff. "NEW JERSEY LOSES OLDEST PAPER", The Palm Beach Post, January 3, 1992. Accessed March 21, 2012. "The Daily Journal, the state's oldest newspaper, will close Friday after losing money for two years. Publisher Richard J. Vezza wouldn't say how much money the 212-year-old newspaper had lost. Most of its 84 employees will be laid off."

- ^ Locality Search, State of New Jersey. Accessed May 21, 2015.

- ^ Areas touching Chatham, MapIt. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- ^ Morris County Municipalities Map, Morris County, New Jersey Department of Planning and Preservation. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- ^ New Jersey Municipal Boundaries, New Jersey Department of Transportation. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- ^ The Passaic River, Great Swamp Watershed Association. Accessed March 23, 2020. "The upper section of the River, after leaving the gorge, flows north-west between Long Hill Township and the Watchung Mountains, skirting the lower edge of the Great Swamp Watershed. It passes through Long Hill Township, Berkeley Heights, and Summit before passing under Route 124 at the border of Chatham Borough and Millburn."

- ^ Staff. "Finding Aid to the Jersey Jetport Site Association Collection, 1959-1976". North Jersey History & Genealogy Center. Morristown and Morris Township Library. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ Hamilton, Leonard W., Ph.D., Keynote Address to the Tenth Anniversary Celebration Archived September 7, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, Ten Towns Committee (Great Swamp Watershed Management Committee), Sustainable Stewardship, June 24, 2005

- ^ Wright, George Cable. "Jetport Foes Map Trenton Protest; Morris and Union Residents Plan Mass Attendance at Hearing Set by Meyner; Governor is Assailed; Group Opposes His Intention to Veto Measure Barring Field in North Jersey", The New York Times, July 8, 1961. Accessed March 21, 2012. "Hickory Tree, Green Village, New Vernon, Chatham and surrounding hamlets, villages and towns in Morris and Union Counties made final plans tonight for an invasion of Trenton on Wednesday to oppose any jetport near here."

- ^ Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge, United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Accessed March 21, 2012. "The Great Swamp NWR is located in Morris County, New Jersey, about 26 miles west of Manhattan's Times Square. The refuge was established by an act of Congress on November 3, 1960. It consists of 7,768 acres of varied habitats and over the years, the refuge has become a resting and feeding area for more than 244 species of birds."

- ^ Origin and History: Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge, United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Accessed March 21, 2012.

- ^ Average Weather for Chatham, New Jersey (07928) - Temperature and Precipitation[permanent dead link], Weather.com. Accessed September 27, 2014.

- ^ Report on Population of the United States at the Eleventh Census: 1890. Part I, p. 239. United States Census Bureau, 1895. Accessed October 20, 2016.

- ^ Compendium of censuses 1726-1905: together with the tabulated returns of 1905, New Jersey Department of State, 1906. Accessed October 8, 2013.

- ^ Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910: Population by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions, 1910, 1900, 1890, United States Census Bureau, p. 338. Accessed December 17, 2012.

- ^ Fifteenth Census of the United States : 1930 - Population Volume I, United States Census Bureau, p. 714. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- ^ Table 6: New Jersey Resident Population by Municipality: 1940 - 2000, Workforce New Jersey Public Information Network, August 2001. Accessed May 1, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Census 2000 Profiles of Demographic / Social / Economic / Housing Characteristics for Chatham borough, New Jersey Archived July 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 17, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e DP-1: Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000 - Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data for Chatham borough, Morris County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 17, 2012.

- ^ DP03: Selected Economic Characteristics from the 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates for Chatham borough, Morris County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- ^ Median Household, Family, Per-Capita Income: State, County, Municipality and Census Designated Place (CDP) With Municipalities Ranked by Per Capita Income; 2010 5-year ACS estimates, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed June 3, 2020.

- ^ Lent, James. "From a little yellow house in Chatham 45 years ago, Weichert Realtors was born", Chatham Courier, September 18, 2014. Accessed February 14, 2023. "The Chatham office is still run out of the same little yellow building Weichert opened in 1969 but Weichert Realtors itself has expanded to many of the 50 United States and Canada. With hundreds of sales offices and thousands of sales representatives, Weichert has become one of the country’s largest Realtors."

- ^ Inventory of Municipal Forms of Government in New Jersey, Rutgers University Center for Government Studies, July 1, 2011. Accessed June 1, 2023.

- ^ Cerra, Michael F. "Forms of Government: Everything You've Always Wanted to Know, But Were Afraid to Ask" Archived September 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey State League of Municipalities. Accessed November 30, 2014.

- ^ "Forms of Municipal Government in New Jersey", p. 6. Rutgers University Center for Government Studies. Accessed June 1, 2023.

- ^ 2024 Municipal Data Sheet, Borough of Chatham. Accessed April 25, 2023.

- ^ Morris County Manual 2024, Morris County, New Jersey Clerk. Accessed May 1, 2024.

- ^ Morris County Municipal Elected Officials For The Year 2024, Morris County, New Jersey Clerk, updated March 20, 2024. Accessed May 1, 2024.

- ^ General Election November 7, 2023 Official Results, Morris County, New Jersey Clerk, updated December 11, 2023. Accessed January 1, 2024.

- ^ General Election November 8, 2022, Official Results, Morris County, New Jersey, updated November 28, 2022. Accessed January 1, 2023.

- ^ General Election Winners For November 2, 2021, Morris County, New Jersey Clerk. Accessed January 1, 2022.

- ^ Plan Components Report, New Jersey Redistricting Commission, December 23, 2011. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- ^ Municipalities Sorted by 2011-2020 Legislative District, New Jersey Department of State. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- ^ 2019 New Jersey Citizen's Guide to Government, New Jersey League of Women Voters. Accessed October 30, 2019.

- ^ Districts by Number for 2011-2020, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 6, 2013.

- ^ Directory of Representatives: New Jersey, United States House of Representatives. Accessed January 3, 2019.

- ^ U.S. Sen. Cory Booker cruises past Republican challenger Rik Mehta in New Jersey, PhillyVoice. Accessed April 30, 2021. "He now owns a home and lives in Newark's Central Ward community."

- ^ Biography of Bob Menendez, United States Senate, January 26, 2015. "Menendez, who started his political career in Union City, moved in September from Paramus to one of Harrison's new apartment buildings near the town's PATH station.."

- ^ Home, sweet home: Bob Menendez back in Hudson County. nj.com. Accessed April 30, 2021. "Booker, Cory A. - (D - NJ) Class II; Menendez, Robert - (D - NJ) Class I"

- ^ Legislative Roster for District 21, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 18, 2024.

- ^ Board of County Commissioners, Morris County, New Jersey. Accessed June 1, 2022. "Morris County is governed by a seven-member Board of County Commissioners, who serve three-year terms."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Morris County Manual 2022, Morris County Clerk. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- ^ Tayfun Selen, Morris County, New Jersey. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- ^ John Krickus, Morris County, New Jersey. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- ^ Douglas R. Cabana, Morris County, New Jersey. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- ^ Thomas J. Mastrangelo, Morris County, New Jersey. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- ^ Stephen H. Shaw, Morris County, New Jersey. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- ^ Deborah Smith, Morris County, New Jersey. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- ^ Commissioners, Morris County, New Jersey. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- ^ Ann F. Grossi, Esq., Office of the Morris County Clerk. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- ^ Clerks, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- ^ About Us: Sheriff James M. Gannon, Morris County Sheriff's Office. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- ^ Sheriffs, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- ^ Surrogate Heather J. Darling, Esq., Morris County, New Jersey. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- ^ Surrogates, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed June 1, 2022.

- ^ Voter Registration Summary - Morris, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, March 23, 2011. Accessed December 17, 2012.

- ^ "Presidential General Election Results - November 6, 2012 - Morris County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. March 15, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Number of Registered Voters and Ballots Cast - November 6, 2012 - General Election Results - Morris County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. March 15, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ 2008 Presidential General Election Results: Morris County, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 23, 2008. Accessed December 17, 2012.

- ^ 2004 Presidential Election: Morris County, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 13, 2004. Accessed December 17, 2012.

- ^ "Governor - Morris County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. January 29, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Number of Registered Voters and Ballots Cast - November 5, 2013 - General Election Results - Morris County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. January 29, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ 2009 Governor: Morris County Archived October 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 31, 2009. Accessed December 17, 2012.

- ^ Joint Municipal Court, Township of Chatham. Accessed November 21, 2016. "The Joint Municipal Court serves five towns: Borough of Madison, Borough of Chatham, Township of Chatham, Township of Harding, and the Township of Morris."

- ^ Joint Municipal Court, Borough of Madison. Accessed November 21, 2016. The Joint Municipal Court serves 5 towns: Borough of Madison, Borough of Chatham, Township of Chatham, Township of Harding, and the Township of Morris."

- ^ Staff. "Fishawack Festival held in downtown Chatham on June 8", Independent Press, June 6, 2013. Accessed July 27, 2015. "Fishawack was the Lenni Lenape Indian name for the Passaic River and Chatham was located at the narrowest part making it the Crossing of the Fishawack in the Valley of the Great Watchung, according to John T. Cunningham's book, Chatham at the Crossing of the Fishawack... In 1971, a Chamber of Commerce sidewalk sale day, called Fishawack Day, was held. Thus began an event, which in time was adopted by Fishawack Inc., the governing body of volunteers who turned it into a big biennial town-wide Festival."

- ^ School District of the Chathams District Policy 0110 - Identification, School District of the Chathams. Accessed July 15, 2022. "Purpose: The Board of Education exists for the purpose of providing a thorough and efficient system of free public education in grades Pre-Kindergarten through twelve in the Chatham School District. Composition: The School District of the Chathams is comprised of all the area within the municipal boundaries of Chatham Borough and Chatham Township in the County of Morris."

- ^ Padawer, Ruth. "Side By Side: Thirty years ago, Chatham Township was fighting—literally—for respect from Chatham Borough. Now it finishes first among the state's 566 municipalities in our biannual ranking. The Borough's response? 'Way to go!'", New Jersey Monthly, February 19, 2008. Accessed September 27, 2014. "The high schools had to scramble to offer the Advanced Placement classes and electives that the new era required. Kids from one school would go to the other for particular classes, as if it were an extension of the same campus. By 1986, after a contentious vote in both towns, the two districts merged."

- ^ Belluscio, Frank. "No Surprise: The State Wants Only K-12 Districts" Archived January 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, School Leader, New Jersey School Boards Association, January / February 2009. Accessed September 27, 2014. "Since 1982, only four locally initiated regionalization proposals have succeeded:... School District of the Chathams (1986)—combining of the K-12 Chatham borough school district with the K-12 Chatham Township district."

- ^ Walsh, Jeremy. "Chatham High School celebrates past, present with centennial and graduation celebration", The Star-Ledger, June 26, 2011, updated March 31, 2019. Accessed January 27, 2022. "The year 1911 was a time of auspicious beginnings.... And in the Chathams, six teens, their youth preserved today in a faded photograph, became the first class to graduate from the newly accredited Chatham High School.... The school building, then only six months old, is now Chatham Borough Hall."

- ^ District information for School District Of The Chathams, National Center for Education Statistics. Accessed February 15, 2022.

- ^ School Data for the School District of the Chathams, National Center for Education Statistics. Accessed February 15, 2022.

- ^ Milton Avenue School, School District of the Chathams. Accessed July 15, 2022.

- ^ Southern Boulevard School, School District of the Chathams. Accessed July 15, 2022.

- ^ Washington Avenue School, School District of the Chathams. Accessed July 15, 2022.

- ^ Lafayette School, School District of the Chathams. Accessed July 15, 2022.

- ^ Chatham Middle School, School District of the Chathams. Accessed July 15, 2022.

- ^ Chatham High School, School District of the Chathams. Accessed July 15, 2022.

- ^ School Performance Reports for the School District of the Chathams, New Jersey Department of Education. Accessed March 31, 2024.

- ^ New Jersey School Directory for the School District of the Chathams, New Jersey Department of Education. Accessed February 1, 2024.

- ^ Board of Education Members, School District of the Chathams. Accessed July 15, 2022.

- ^ Blue Ribbon Schools Program: Schools Recognized 1982 Through 2013, United States Department of Education. Accessed September 27, 2014.

- ^ Goldman, Jeff. "Which N.J. schools were named to national 'Blue Ribbon' list?", NJ Advance Media for NJ.com, October 2, 2014. Accessed December 31, 2014. "Eleven New Jersey schools have been named to the annual National Blue Ribbon list, the U.S. Department of Education announced Tuesday."

- ^ 2014 National Blue Ribbon Schools All Public and Private, United States Department of Education. Accessed December 31, 2014.

- ^ Staff. "Top Schools Alphabetical List 2014", New Jersey Monthly, September 2, 2014. Accessed September 5, 2014.

- ^ Staff. "The Top New Jersey High Schools: Alphabetical", New Jersey Monthly, August 16, 2012. Accessed September 23, 2012.

- ^ Morris County Elementary Schools Archived July 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Roman Catholic Diocese of Paterson. Accessed August 22, 2011.

- ^ Morris County Mileage by Municipality and Jurisdiction, New Jersey Department of Transportation, May 2010. Accessed July 18, 2014.

- ^ Applebome, Peter. "Our Towns; Making A Molehill Out of a Bump", The New York Times, April 19, 2006. Accessed June 24, 2013. "But it turns out that, inexplicably forgotten as it seems to be, there is plenty of documentation for Chatham's place in history. Here, a century ago this week, it seems, humans created one of the hallmarks of the automotive age: the speed bump."

- ^ Staff. "'Bumps' Check Autos.; Crowds Cheer as Machines Strike Them and Jump Into the Air.", The New York Times, April 24, 1906. Accessed June 24, 2013.

- ^ Chatham station, NJ Transit. Accessed September 27, 2014.

- ^ Morristown Line Archived October 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, NJ Transit. Accessed September 27, 2014.

- ^ Riding the Bus, Morris County, New Jersey. Accessed April 26, 2023.

- ^ Morris County System Map Archived June 19, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, NJ Transit. Accessed July 27, 2015.

- ^ Morris County Bus / Rail Connections, NJ Transit. Accessed October 8, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c About the Library, Library of The Chathams. Accessed March 21, 2012.

- ^ Ivers, Marianne. "Chatham revitalizing sisterhood relationship with Esternay", Independent Press, August 9, 2010. Accessed March 21, 2012. "Time after time Chatham residents pass the sign at the entrance to the borough, announcing Esternay as Chatham's sister town. Yet there has been little contact with the French community during the past 10 years — until just recently."

- ^ Ben Bailey profile Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Zanies Comedy Night Club, accessed March 27, 2013. "Ben Bailey is a young comedian on the rise. In the fall of 1992, Ben left his home in Chatham, New Jersey and flew to Los Angeles with only forty dollars and a backpack full of clothes."

- ^ Fowler, Linda. "From the archives: Ben Bailey in his Cash Cab, circa 2009", Inside Jersey, December 9, 2017. Accessed July 30, 2019. "Bailey grew up in Chatham Borough ('yeah, the rough neighborhood'), where his dad was an executive for Chase Manhattan Bank and his mom worked for a time in the career center at Drew University."

- ^ Salmond, Jessica. "Benz steps up to lead CONA", Sarasota Observer, January 21, 2015. Accessed January 12, 2018. "Kafi Benz - Born: Chatham, N.J. Moved to Sarasota: 1982"

- ^ Cichowski, John. "Morris Voters Reelect 3 Gop Legislators", The Record, November 6, 1991. Accessed November 18, 2008. "Brown of Chatham Borough led Democrat Drew Britcher of Parsippany-Troy Hills, 27,381 to 7,563 to win her third term."

- ^ Townsend, Cara. "Trailblazer Leanna Brown Honored by Chatham GOP", TheAlternativePress.com, February 10, 2013, Accessed February 18, 2013. "Longtime Chatham resident Leanna Brown had many firsts in politics. She was the first woman to serve on the Borough Council, the first woman to win a seat in the New Jersey Assembly, and the first woman elected to the State Senate."

- ^ "Our Campaigns – Senate 26th Legislative District – History". OurCampaigns.com. Accessed February 19, 2013. Site content indicates election results for Republican Leanna Brown of Chatham Borough in her three wins for State senate, including defeating Democrat Drew Britcher by 34,063 to 9,514 votes for her third Senate term in 1991.

- ^ Staff. "Edward E. Bruen, A Realty Dealer. First Mayor of East Orange Established Firm 53 Years Ago. Dies at 78. Served Elevated Lines. Secretary to Thomas Peeples of Manhattan Company. Descendant of Settlers", The New York Times, May 12, 1938. Accessed July 24, 2018. "Born in Chatham, Mr. Bruen was a descendant of settlers there and of Obadiah Bruen, who went from Connecticut to Newark in 1666."

- ^ Edward Everett Bruen, Political Graveyard.

- ^ Ivers, Marianne. "Chatham Borough Mayor Bruce Harris honored at Historical Society event", The Independent Press, April 13, 2015. Accessed February 12, 2017. "When Harris and his partner Marc Boisclair moved to New Jersey in 1981, they chose Chatham Borough 'because of its small town character and sense of community', Harris said... From 2004 to 2012 Harris served on the Chatham Borough Council. He was elected mayor in January 2012."

- ^ Bruce, Edna. "Along the Way", The Chatham Press, August 26, 1960. Accessed January 27, 2022, via Newspapers.com. "Constance J. McNeely of 16 N. Hillside Avenue has been awarded one of the 202 freshman competitive scholarships at the University of Pennsylvania. A recent Chatham High School graduate, Miss McNeely will enter the College of Liberal Arts for Women next month."

- ^ Shepard Kollock Park Archived May 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, ChathamPatch, accessed March 27, 2013.

- ^ Staff. "Reagan to Nominate Former Interior Aide As Labor Secretary", The New York Times, November 3, 1987. Accessed March 21, 2012. "Mrs. McLaughlin was born in 1941 in Chatham, N.J."

- ^ Neighborhood House, real estate market get boost from Jets, New Jersey On-Line. Accessed December 9, 2010. "Offensive lineman Nick Mangold put it another way. The 24-year-old and his wife have been busy in recent weeks moving into their new two-story house in Chatham Borough, meeting neighbors."

- ^ via Associated Press. "Smathers Makes His West Point Choices", The Daily Home News, June 26, 1942. Accessed February 14, 2023, via Newspapers.com. "The senator yesterday also named Joseph C. McDonough, 25 Oliver street, Chatham, his first alternate appointee..."

- ^ Berman, Zach. "A man of his words: Play-by-play is Bob Papa's work, love", The Star-Ledger, January 2, 2011. Accessed March 21, 2012. "There's one subtle staple in every Bob Papa broadcast.... In the opening segment, with Jen and their three sons watching and waiting in their Chatham home, Papa delivered in the most understated of ways."

- ^ Staff. "Winners Of Pulitzer Prizes In Journalism, Letters And The Arts", The New York Times, April 17, 1987. Accessed March 6, 2013. "Mr. Shipler was born in Chatham, N.J., graduated from Dartmouth College and joined The Times as a news clerk in 1966."

- ^ Two Reporters bios

- ^ Barry, Ellen. "Barbara Stanley, Influential Suicide Researcher, Dies at 73", The New York Times, January 29, 2023. Accessed February 14, 2023. "In addition to her daughter, Dr. Stanley, who lived in Chatham, N.J., is survived by her son, Thomas Stanley, and her siblings, John Hrevnack, Michael Hrevnack and Joanne Kennedy."

- ^ Havsy, Jane. "Chatham teen to represent U.S. in CONCACAF U-17 championship", Daily Record, April 22, 2019. Accessed October 1, 2019. "John Tolkin of Chatham has been called in to the U.S. Soccer under-17 national team ahead of the CONCACAF U-17 Championship at IMG Academy in Bradenton, Florida."

- ^ "Montgomery Ward: The World's First Mail-Order Business", backed up by the Internet Archive as of May 16, 2008. Accessed March 6, 2013. "Aaron Montgomery Ward was born on February 17, 1844, in Chatham, New Jersey, to a family whose forebears had served as officers in the French and Indian War as well as in the American Revolution."

- ^ Burros, Marian. "Alice Waters: Food Revolutionary", The New York Times, August 4, 1996. Accessed March 21, 2012. "Alice Louise Waters, one of four daughters born in Chatham, N.J., is no longer just a restaurateur. Chez Panisse, which she opened just to entertain her friends, has become a shrine to the new American cooking and a mecca of the culinary world."

Historical research resources[edit]

- Anderson, John R. Shepard Kollock: Editor for Freedom. Chatham, New Jersey: Chatham Historical Society, 1975.

- Cunningham, John T. Chatham: At the Crossing of the Fishawack. Chatham, New Jersey: Chatham Historical Society, 1967.

- Philhower, Charles A., Brief History of Chatham, Morris County, New Jersey. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1914.

- Thayer, Theodore. Colonial and Revolutionary Morris County. The Morris County Heritage Commission. (government publication)

- Vanderpoel, Ambrose Ely. History of Chatham, New Jersey. New York: Charles Francis Press, 1921. Reprint. Chatham, New Jersey: Chatham Historical Society, 1959.

- White, Donald Wallace. A Village at War: Chatham and the American Revolution. Rutherford, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1979.

- ______________. Chatham. Dover, New Hampshire: Arcadia Publishing, 1997.

- ______________. "Historic Minisink Trail". Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society. 8, (January–October 1923): 199–205.

- ______________. "Indians of the Morris County Area". Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society. 54 (October 1936): 248–267.

- Design Guidelines Manual For Rehabilitation and Construction in the Main Street Historic District. Chatham, New Jersey: Chatham Borough Historic Preservation Commission, 1994. (government publication)