Fight for $15

This article needs to be updated. (June 2023) |

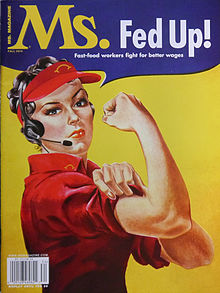

The Fight for $15 is an American political movement advocating for the minimum wage to be raised to USD$15 per hour. The federal minimum wage was last set at $7.25 per hour in 2009. The movement has involved strikes by child care, home healthcare, airport, gas station, convenience store, and fast food workers for increased wages and the right to form a labor union. The "Fight for $15" movement started in 2012, in response to workers' inability to cover their costs on such a low salary, as well as the stressful work conditions of many of the service jobs which pay the minimum wage.

The movement has seen successes on the state and local level. California, Massachusetts, New York (downstate only), Maryland, New Jersey, Illinois, Connecticut, Florida, Delaware, and Nebraska have passed laws that gradually raise their state minimum wage to at least $15 per hour.[4][5] Major cities such as San Francisco, New York City and Seattle, where the cost of living is significantly higher, have already raised their municipal minimum wage to $15 per hour with some exceptions. On the federal level, the $15 proposal has become significantly more popular among Democratic politicians in the past few years, and was added to the party's platform in 2016 after Bernie Sanders advocated for it in his presidential campaign.[6]

In 2019, the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives passed the Raise the Wage Act, which would have gradually raised the minimum wage to $15 per hour. It was not taken up in the Republican-controlled Senate. In January 2021, Democrats in the Senate and House of Representatives reintroduced the bill.[7] In February 2021, the Congressional Budget Office released a report on the Raise the Wage Act of 2021 which estimated that incrementally raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2025 would benefit 17 million workers, but would also reduce employment by 1.4 million people.[8][9][10] On February 27, 2021, the Democratic-controlled House passed the American Rescue Plan pandemic relief package, which included a gradual minimum wage increase to $15 per hour.[11] The measure was ultimately removed from the Senate version of the bill.[12]

Strikes and protests in the United States

[edit]

On November 29, 2012, over 100 fast-food workers from McDonald's, Burger King, Wendy's, Domino's, Papa John's, Kentucky Fried Chicken and Pizza Hut walked off their jobs in New York City, New York in strike for higher wages, better working conditions and the right to form a union without retaliation from their managers.[16][17] Many workers were making the minimum wage at the time. However, many allegedly were making, and are currently making, less than the minimum wage due to wage theft on the part of their employers.[18] This was the largest strike in the history of the fast-food industry.[19] Earning less than a living wage has forced many fast-food workers to have multiple jobs and obtain forms of government assistance such as food stamps in order to afford basic food, shelter and clothing.[20] This rate is declared to be below what the Massachusetts Institute of Technology considers to be a "living wage" (based on cost of living and necessary expenses) for all five boroughs of New York City.[21] Time described this initial effort as seizing on the public's concern with economic inequality in the United States as stimulated by the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011 and 2012.[22]

The strike was organized by over 40 personnel from New York Communities for Change, Service Employees International Union, UnitedNY, and the Black Institute.[23] On April 4, 2013 (the 45th anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. during the Memphis sanitation strike), more than 200 fast-food workers went on strike in New York City. Hundreds of other workers went on strike in Chicago on April 24, in Detroit on May 10, in St. Louis on May 9 and 10, in Milwaukee on May 15 and in Seattle on May 30.[24][25][26]

On July 29, approximately 2,200 workers went on strike in all of the cities where fast-food workers had previously gone on strike with the addition of Flint, Michigan and Kansas City, Missouri.[27][28]

A coordinated national fast-food strike took place on August 29. In Seattle, Washington, the protests influenced candidate Ed Murray to release an "Economic Opportunity Agenda for Seattle". This agenda was later partially adopted by the Seattle city council, which voted to raise the minimum wage to $15.[29]

On December 6, 2013, further fast food strikes occurred nationwide in a campaign aimed at raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour.[30]

On September 4, 2014, another national strike took place in more than 150 cities, but this time thousands of Home care workers joined the fast food workers.[31][32] In another departure from previous protests, organizers shifted tactics and encouraged acts of civil disobedience such as sit ins to further draw attention to their cause. Between 159 and 436 arrests were made.[33][34] Striking fast food workers from Ferguson, Missouri, were arrested in Times Square, New York City, in solidarity with workers there nearly a month after the police Shooting of Michael Brown.[35]

On December 4, 2014, thousands of fast food workers walked off of the job in 190 U.S. cities to engage in further protests for $15 an hour and union representation, and were joined by caregivers, airport workers, and employees at discount and convenience stores. The strikes were also bolstered by anger over the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner at the hands of police. Chants of "15 and a union" were accompanied by "Hands up, don't shoot" and "I can't breathe". Kendall Fells, organizing director for Fast Food Forward, claimed the strikes were "fights against injustice in the U.S."[36][37][38] Organizers from Black Lives Matter supported the strike.[39][40]

On April 15, 2015, tens of thousands of fast food workers in more than 200 cities took to the streets again in what labor organizers have described as the largest protest by low-wage workers in US history. In their campaign to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour, labor activists and fast food workers were joined by home care assistants, Walmart workers, child-care aides, airport workers, adjunct professors and others who work low-wage jobs.[41] Gary Chaison, a professor of industrial relations at Clark University, noted that this protest movement is unique among labor disputes:

What is really significant about the Fight for $15 movement is – most labor disputes, look inside, they're about a group of workers covered by a collective bargaining agreement. In the Fight for $15, unions are helping to organize on a community basis, a group of workers who are on the fringe of the economy. It's not about union members protecting themselves. It's about moving other people up. This is the whole civil rights movement all over again.

Another strike took place in November 2015.[42] U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) voiced his support for the striking workers and a $15 an hour federal minimum wage at a Fight for $15 rally in Washington DC.[43][44]

Global strikes and protests

[edit]On May 15, 2014, fast food workers in countries around the world, including Brazil, the United Kingdom, Japan, and the U.S., went on strike to protest low wages in fast food restaurants.[45] The strikes took place in 230 cities as workers demanded a $15 minimum wage and the right to unionize without fear of retaliation.[46] Less than a week later, a mass protest at McDonald's headquarters in Oak Brook, Illinois took place and resulted in over 100 protesters being arrested, including workers, church leaders and Service Employees International Union president Mary Kay Henry, and a partial shutdown of the McDonald's campus.[47] According to the movement organizers, the protest took place in 30 cities in Japan, 5 cities in Brazil, 3 cities in India and 20 cities in Britain.[48] The labor federation with over 12 million workers in 126 countries joined the protest to help propel the effort.[48]

Industry officials say that only a small percentage of fast-food jobs pay the minimum wage and that those are largely entry-level jobs for workers under 25. Backers of the movement for higher pay point to studies saying that the average age of fast food workers is 29 and that more than one-fourth are parents raising children.[49] According to Mary Kay Henry, the president of service employees international union "fast food workers in many other parts of the world face the same corporate policy. Low pay, no guaranteed hours and no benefits". According to her, such unfairness in the wages exist due to the lack of opportunity for these workers to unionize.[50] According to one of McDonald's workers, the minimum wages is not enough to take care of his kids and their education. However, some analysts at conservative think tanks say that increasing the wages will have harmful consequences on the hiring rate which could cause a large number of unemployed people.[51][52]

Julie Sherry, an organizer of the protests in the United Kingdom, which have taken place on several occasions since January, projected that 100 workers would meet at 4 pm London time at the McDonald's in Trafalgar Square. They planned to carry signs declaring, "Fast Food Rights" and "Hungry for Justice" and to chant, "Zero Hours, No Way" — a reference to contracts in the UK that an estimated 90% of McDonald's workers have signed that don't guarantee them any hours but expect workers to come in whenever they are called.[53] Organizers say that in the Philippines, workers held a flash mob inside a Manila McDonald's, singing and dancing to "Let It Go", from the movie Frozen, urging McDonald's to "let go" of its low wages and allow workers to organize.[54] Protesters in Brussels shut down a McDonald's at lunchtime, and protesters in Mumbai who were threatened with arrests by local police were undeterred. Japan saw protests in nearly every prefecture and showed solidarity with U.S. workers by calling on McDonald's to pay Japanese workers 1,500 yen.[54]

This is not the first time that the workers protested against the low wages. On November 29, 2012, about 200 workers protested at a McDonald's at Madison Avenue and 40th Street chanting "Hey, hey, what do you say? We demand fair pay".[55] According to Kate Bronfenbrenner, director of labor education research at the Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations, the workers global campaign is not a new idea. To determine the origins of this approach, you have to take a trip back to the 1800s, when workers in Britain and India jointly protested the way the East India Company treated its Indian workers.[56]

Some economists and labor activists are looking to the Danish socioeconomic model, with its powerful unions and living wages for fast-food workers, as evidence that companies can adapt in nations that have high wage floors, and that such a model can serve as an example to the United States. According to John Schmitt of the Center for Economic and Policy Research: "We see from Denmark that it's possible to run a profitable fast-food business while paying workers these kinds of wages." Stephen J. Caldeira, President and CEO of the International Franchise Association, an organization that has many fast-food companies as members, strongly disagrees and claims that "trying to compare the business and labor practices in Denmark and the U.S. is like comparing apples to autos."[57]

A January 2015 study by economists at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst found that fast food companies could absorb an incremental wage hike from $7.25 to $15 without shedding jobs by reducing turnover and slightly increasing prices.[58]

Affected industries

[edit]Restaurant industry

[edit]The impact on employers and workers within the restaurant industry is a major focus of the Fight for $15 movement. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, restaurants and other food services employ about sixty percent of all workers paid at or below the minimum wage, as of 2018.[59] Common responses to minimum wage increases include restaurant operators cutting employee hours and raising menu prices.[60] In cities such as New York City and Seattle that have already implemented a $15 minimum wage for most businesses, menu price increases have been a trend.[61] Politicians, economists, restaurant owners and workers continue to debate the economic viability and benefits of a federally mandated $15 minimum wage.

Economists of the Economic Policy Institute have largely come out in support of a $15 federal minimum wage.[62] Their outlined plan entails a gradual increase, reaching $15 by 2024. Fast-food restaurants are a key focus in the Fight for $15 movement. Some argue that turnover reductions, trend increases in sales growth, and modest annual price increases would allow for this bump in minimum wage without forcing the restaurants to shed employees.[63] While most advocates acknowledge rising prices as a result of the higher wages, they generally accept this outcome and believe it will not have a major negative impact on dining/overall sales. Advocates for the movement also point to research that finds the average estimated employment effect of minimum wage increases to be very small.[64]

A common argument against raising the minimum wage in restaurants to $15 is that it could cause cuts to employee hours, as well as potential layoffs or restaurant closures.[60]

Waiters, bartenders, and other food service workers who primarily work for tips may utilize the federal tipped minimum wage, which is currently $2.13 an hour. A tip credit is the difference between their minimum wage and the cash wage an employee is paid during a pay period, accounting for tips that do not add up to the federal minimum wage. Many advocates for a $15 minimum wage, including restaurant owners, believe that restaurants should get rid of the tip credit pay structure, as they find it is not beneficial to low wage restaurant workers.[65]

Retail

[edit]According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 11,302,000 workers in the retail industry were paid hourly rates at or below the federal minimum wage in 2018.[66] Retail workers account for a significant portion of those affected by the minimum wage, as major retailers such as Target and Walmart are a big focus on this issue. Recently, some companies, including Target and Best Buy, have committed to boost their starting hourly wage to $15 an hour, regardless of local/federal minimum wage mandates.[67][68] As pressure grows, more stores are increasing their hourly rates both to satisfy political/social demands, while also benefiting from happier, more productive workers.[69]

Health care

[edit]Health care is one of the largest industries in the United States, with about 18.6 million workers as of 2019 and the numbers are growing.[70] According to The Brookings Institution, there were nearly 7 million people in low-paid health jobs in 2019 in the United States.[71] The median wage was $13.48 an hour for jobs in health care support, service, and direct care.[71] Given the discrepancy between wages in these categories and significantly higher pay for doctors and nurses, the fight for a living wage in health care has gained support.

Criticism and responses

[edit]Arguments for and against the movement are the same as arguments for and against the minimum wage. Opponents generally claim that higher wages will result in fewer working hours for each worker (nullifying the increased rate), increased unemployment, and higher consumer prices. Proponents generally point to the benefits for workers who earn a higher hourly rate, and claim that the higher prices are tolerable and promote a more equitable distribution of wealth. Economists disagree whether higher minimum wages cause unemployment among low-wage workers. In 2017 and 2018, the unemployment rate was very low nationally, and several states hit record low unemployment levels, with no clear pattern across high-wage vs. low-wage states.[72]

Former McDonald's CEO and President Ed Rensi cited the Fight for $15 movement as the reason for the installation of automated ordering kiosks at the chain's restaurants nationwide, which he says is an example of higher minimum wages causing unemployment.[73] Increased automation is treated as a benefit of a higher minimum wage by some advocates,[74] and economists generally view automation as a net positive because it increases labor productivity and allows employers to pay higher wages to workers because they are shifted to higher-value tasks.

Rensi and other critics say that some businesses, especially small businesses, cannot afford the capital investments needed for automation, or simply cannot afford higher labor costs. As a result, they are either driven out of business or relocate to lower-wage jurisdictions. Such cases are portrayed on the advocacy web site Faces of $15. Other businesses, including Amazon.com,[75] have voluntarily pledged to pay workers no less than $15 per hour (though through Amazon Robotics the company is also investing heavily in automation). Observers say businesses do this to reduce turnover and training costs, to compete for quality workers in a tight labor market, and to avoid negative publicity.

Other critics claim that an increased minimum wage would accelerate the speed of automation and displacement of minimum wage jobs, as employers replace low-skilled workers with machines, AI, and self-driving vehicles in common job sectors: retail, fast food service, call centers, trucking, and accounting. Universal basic income has been proposed as a progressive alternative.[76]

Achievements

[edit]

In the state of Washington, two cities have been described as test cases for the $15 minimum wage. In SeaTac, a small suburban community whose economy centers around the Seattle–Tacoma International Airport, the minimum wage was increased to $15 per hour in 2014 without any intermediate stages, which resulted in heavy media attention.[77] In 2014, Seattle became the first major city in the US to raise the minimum wage to $15 per hour. The campaign was spearheaded by socialist city councilmember Kshama Sawant with support from a broad coalition of labor unions (under the leadership of state labor council president Jeff Johnson), faith groups, and other organizations.[78] Seattle's minimum wage for large employers was raised to $15.45 in 2018 and $16 in 2019. Studies of Seattle's workforce have shown no decline in employment and tangible benefits for workers.[79]

The Fight for $15 movement has succeeded in several states and cities in raising the minimum wage to $15 or more per hour. In California, the minimum wage has been raised in stages since 2016, starting from a rate of $10 per hour, and will reach $15 per hour in 2022.[80] Several cities in California have already raised the minimum wage to $15 or more, including Berkeley, El Cerrito, Emeryville, Mountain View, San Francisco, San Jose, San Mateo, and Sunnyvale.[81] Massachusetts passed the "Grand Bargain" law in 2018, which raises the state minimum wage to $15 per hour by 2023, after yearly increases from the $11/hour minimum reached in 2017.[82][83] The state of New York will raise the minimum wage in the Downstate region to $15 per hour in 2021, while in Upstate New York the minimum wage will be set by the Commissioner of Labor no lower than $12.50 per hour.[84] In New Jersey, the minimum wage will reach $15 per hour in 2024.[85] In March 2019, both Maryland and Illinois have explicitly passed laws or statutes on the process of "gradually increases over several years" raising their state minimum wage to at least $15 per hour.[5] In May 2019, Connecticut passed a $15 per hour law. On November 3, 2020, 61% of Florida voters passed Amendment 2, which raises the minimum wage to $10.00 per hour effective September 30, 2021, and then increases it annually by $1.00 per hour until the minimum wage reaches $15.00 per hour in 2026 and then reverts to being adjusted annually for inflation.

When the New York State Wage Board announced that the minimum wage in New York City would be raised to $15 an hour by December 31, 2018, Patrick McGeehan argued in the New York Times that it was a direct consequence of the Fight for $15 protests, and that "the labor protest movement that fast-food workers in New York City began nearly three years ago has led to higher wages for workers all across the country."[86]

A $15/hour minimum wage at Amazon took effect in November 2018.[75]

It is estimated that as a result of state and local minimum wage laws adopted since the Fight $15 began, an estimated 26 million workers have won $151 billion in raises.[87][88]

Exceptions

[edit]State and local governments which have raised their minimum wage to $15 per hour have often included exceptions, allowing certain types of employers to pay less or for certain types of employees to receive less. This is typically done with the intent of minimizing any potential negative impacts on the economy.

Employers and industries with labor unions are sometimes exempted from paying their employees the full minimum wage, to encourage the growth of organized labor. As of December 2014, unions were exempt from recent minimum wage increases in Chicago, SeaTac, Washington, and Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, as well as the California cities of Los Angeles, Long Beach, San Jose, Richmond, and Oakland. In San Francisco, a labor union may be exempt if its collective bargaining agreement explicitly waives the minimum wage requirement.[89]

In New Jersey, where the general minimum wage is set to be raised to $15 per hour in 2024, farmworkers are excluded and their minimum wage will be set at $12.50.[85]

Estimated economic impact of federal $15 wage

[edit]In February 2021, the Congressional Budget Office released a report on the Raise the Wage Act of 2021 which estimated that incrementally raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2025 would benefit 17 million workers, but would also reduce employment by 1.4 million people.[8][9][10] It would also lift 0.9 million people out of poverty, possibly raise wages for an additional 10 million workers, and increase the federal budget deficit by $54 billion over ten years by increasing the cost of goods and services paid for by the federal government.[8][9][10] It would also cause prices to rise, and overall economic output to decrease slightly over the next 10 years.[8][90]

A few economists have disputed some of the report's findings. University of California, Berkeley's Michael Reich has estimated that rather than increasing the deficit, a $15 minimum wage could increase federal tax revenue by $65 billion annually, because of increased payroll taxes and government spending on safety net programs is likely to decrease.[10][91] Arindrajit Dube stated that he thought the report's examination of relevant studies was not as comprehensive as a report he recently did and estimated that the job losses would be less than 500,000.[92][93]

See also

[edit]- List of countries by minimum wage

- Income inequality in the United States

- Justice for Workers (Canadian movement)

- Labor history of the United States

- One Fair Wage

- Poverty in the United States

- McDonald's and unions

References

[edit]- ^ a b "State Minimum Wage Laws". Wage and Hour Division (WHD). United States Department of Labor. Click on states on that map to see exact minimum wage info by state. See bottom of page for District of Columbia and U.S. territories. See: table and abbreviations list.

- ^ Wage Rates in American Samoa. Wage and Hour Division of the U.S. Department of Labor.

- ^ "Wage Rate in American Samoa" (PDF). Wage and Hour Division (WHD). United States Department of Labor.

- ^ "Delaware becomes the 10th state (plus Washington, D.C.) to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour". July 19, 2021.

- ^ a b "Maryland just became the sixth state to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour". March 28, 2019.

- ^ Weigel, David (July 9, 2016). "Democrats back $15 minimum wage, but stalemate on Social Security". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Democrats introduce bill to hike federal minimum wage to $15 per hour". CNBC. January 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "The Budgetary Effects of the Raise the Wage Act of 2021" (PDF). Congressional Budget Office. February 1, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c Selyukh, Alina (February 8, 2021). "$15 Minimum Wage Would Reduce Poverty But Cost Jobs, CBO Says". NPR.

Raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2025 would increase wages for at least 17 million people, but also put 1.4 million Americans out of work, according to a study by the Congressional Budget Office released on Monday.

- ^ a b c d Rosenberg, Eli (February 8, 2021). "CBO report finds $15 minimum wage would cost jobs but lower poverty levels". The Washington Post.

Raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour would significantly reduce poverty and increase earnings for millions of low-wage workers, while adding to the federal deficit and cutting overall employment, according to a new study from the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office. ... On one hand, the CBO estimated that raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2025 would cost 1.4 million jobs and increase the deficit by $54 billion over 10 years. But it also estimated the policy would lift 900,000 people out of poverty and raise income for 17 million people — about 1 in 10 workers. Another 10 million who have wages just above that amount could potentially see increases, as well, the CBO reported.

- ^ "American Rescue Plan: What's in the House's $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief plan". The Washington Post. February 27, 2021.

- ^ "Senate passes $1.9 trillion Biden relief bill after voting overnight on amendments, sends measure back to House". The Washington Post. March 6, 2021.

- ^ Consolidated Minimum Wage Table. From: Wage and Hour Division of the U.S. Department of Labor. See abbreviations list.

- ^ Congressional Research Service (March 2, 2023). "State Minimum Wages: An Overview". Chart on page 3.

- ^ FRED Graph. Using U.S. Department of Labor data. Federal Minimum Hourly Wage for Nonfarm Workers for the United States. Inflation adjusted (by FRED) via the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items in U.S. City Average (CPIAUCSL). Run cursor over graph for nominal and real minimum wage by month.

- ^ Resnikoff, Nedd (November 29, 2012). "New York's fast food workers strike. Why now?". MSNBC.

- ^ Semuels, Alana (November 29, 2012). "Fast-food workers walk out in N.Y. amid rising U.S. labor unrest". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Turkewitz, Julie (May 15, 2013). "State Said To Be Reviewing Pay For Fast Food Workers". The New York Times.

- ^ Resnikoff, Ned (November 30, 2012). "After the Strike, Fast Food Workers Expect Support To Grow". MSNBC.

- ^ Migoya, David (October 15, 2013). "Fast Food Workers Cost taxpayers nearly $7 billion in welfare costs". The Denver Post.

- ^ "Living Wage Calculator - Living Wage Calculation for Dutchess County, New York". Livingwage.mit.edu. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ Sanburn, Josh (July 30, 2013). "Fast Food Strikes: Unable to Unionize, Workers Borrow Tactics From 'Occupy'"". Time. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- ^ "NY Fast Food Workers Serve Up a Fight for Economic Justice". February 1, 2013.

- ^ Resnikoff, Ned (April 4, 2013). "Historic fast food strike draws lessons from MLK's last campaign". MSNBC. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ Greenhouse, Steven (November 29, 2012). "With Day of Protests, Fast-Food Workers Seek More Pay". The New York Times.

- ^ Davidson, Paul (May 14, 2013). "Fast-food workers stage protests for higher wages". USA Today.

- ^ "Fast-food workers strike nationwide in protest against wages". Fox News. August 29, 2013.

- ^ Greenhouse, Stephen (July 31, 2013). "A Day's Strike Seeks to Raise Fast-Food Pay". The New York Times.

- ^ Rolf, David (2016). "The Fight for Fifteen: The Right Wage for a Working America". The New Press – via ProQuest Ebook Central.

- ^ "Fast-food workers rally nationwide for higher wages". Los Angeles Times. December 5, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Berman, Jillian (September 4, 2014). "Why This Week's Fast Food Protests Are 'History In The Making'". HuffPost. Retrieved September 4, 2014.

- ^ WFTS Webteam (September 4, 2014). "Fast food workers protest at McDonald's in Tampa, Temple Terrace". abcactionnews.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ Berman, Jillian (September 4, 2014). "Demonstrators Arrested At Fast Food Protests In Cities Across The Country (Photos)". HuffPost. Retrieved September 4, 2014.

- ^ Rushe, Dominic; Gambino, Lauren; Carroll, Rory; Guarino, Mark (September 4, 2014). "Hundreds of fast-food protesters arrested while striking against low wages". The Guardian. Retrieved September 4, 2014.

- ^ Smith, Michael Kirby; Laffin, Ben; Archdeacon, Colin (September 5, 2014). "A Ferguson Activist in New York". The New York Times. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ Gittleson, Kim (December 4, 2014). "US fast food worker protests expand to 190 cities". BBC News.

- ^ Wojcik, John (December 4, 2014). "Fast food workers walk off the job in 190 cities". People's World. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ Margolin, Emma (December 4, 2014). "Fast food workers' strike fueled by other low-wage employees, Eric Garner". MSNBC. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ Greenhouse, Steven (March 30, 2015). "Movement to Increase McDonald's Minimum Wage Broadens Its Tactics". The New York Times. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- ^ Woodman, Spencer (April 16, 2015). "The Biggest Fast-Food Strike in History Was About More Than a $15 Minimum Wage". Vice Media. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- ^ Greenhouse, Steven; Kasperkevic, Jana (April 15, 2015). "Fight for $15 swells into largest protest by low-wage workers in US history". The Guardian. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ "Fast-food workers strike, seeking $15 wage, political muscle". Msn.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ Prupis, Nadia (November 10, 2015). "'Fifteen Bucks and a Union': Bernie Sanders Marches With Striking Workers". Common Dreams.

- ^ Devaney, Tim (November 10, 2015). "Bernie Sanders rallies with striking Capitol workers in the rain". The Hill.

- ^ Jillian Berman (May 15, 2014). America's Terrible Fast Food Pay Has Gone Global, And Workers Are Fighting Back. The Huffington Post. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ Erika Eichelberger (May 15, 2014). Fast-Food Strikes Go Global. Mother Jones. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ Dominic Rushe (May 21, 2014). Over 100 arrested near McDonald's headquarters in protest over low pay. The Guardian. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ^ a b Steven Greenhouse, "fast-food protests spread overseas". The New York Times. May 14, 2014. August 10, 2014

- ^ Steven Greenhouse, "Wage strikes planned at fast-food outlets". The New York Times. December 1, 2013. August 10, 2014

- ^ Steven Greenhouse, "Fast-food protests spread overseas". The New York Times. May 14, 2014. August 10, 2014.

- ^ Bourne, Ryan. "The Case against A $15 Federal Minimum Wage: Q&A". Cato Institute. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Perry, Mark (August 23, 2016). "Minimum wage effect? DC restaurants lost more jobs since January than any 6-month period since 2001 recession". AEI. American Enterprise Institute. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Laura Shin, "fastfood workers protest over minimum wage spread across the globe". Forbes. May 15, 2014. August 10, 2014

- ^ a b Laura Shin, "fast food workers protest over minimum wage spread across the globe". Forbes. May 15, 2014. August 10, 2014

- ^ Steven Greenhouse, "With day of protests fast food workers seek more pay". The New York Times. November 12, 2012. August 10, 2014

- ^ Claire Zillman, "Fast-food strikes: why going global could work". Fortune. May 13, 2014. August 10, 2014

- ^ Liz Alderman and Steven Greenhouse (October 27, 2014). Living Wages, Rarity for U.S. Fast-Food Workers, Served Up in Denmark. The New York Times. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ Ned Resnikoff (January 23, 2015). Report: Fast food industry could survive $15 minimum wage. Al Jazeera America. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- ^ "Characteristics of minimum wage workers, 2018 : BLS Reports: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics". www.bls.gov. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ a b Lucas, Amelia (April 10, 2019). "Higher minimum wage means restaurants raise prices and fewer employee hours, survey finds". CNBC. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Romich, Jennifer L.; Allard, Scott W.; Obara, Emmi E.; Althauser, Anne K.; Buszkiewicz, James H. (March 1, 2020). "Employer Responses to a City-Level Minimum Wage Mandate: Early Evidence from Seattle". Urban Affairs Review. 56 (2): 451–479. doi:10.1177/1078087418787667. ISSN 1078-0874. S2CID 158327553.

- ^ "Economists in support of a federal minimum wage of $15 by 2024". Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Pollin, Robert; Wicks-Lim, Jeannette (July 2, 2016). "A $15 U.S. Minimum Wage: How the Fast-Food Industry Could Adjust Without Shedding Jobs". Journal of Economic Issues. 50 (3): 716–744. doi:10.1080/00213624.2016.1210382. ISSN 0021-3624. S2CID 157629923.

- ^ "Gradually raising the minimum wage to $15 would be good for workers, good for businesses, and good for the economy: Testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Education and Labor". Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Cohen, Amanda (September 6, 2019). "Actually, a Higher Minimum Wage Is Good for Restaurants". Eater. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ "Characteristics of low wage workers, 2018" (PDF). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- ^ Repko, Melissa (June 17, 2020). "Target raises minimum wage to $15 an hour months before its deadline". CNBC. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Friedman, Gillian (July 22, 2020). "Best Buy to join retailers paying a $15 minimum wage". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Fisman, Ray; Luca, Michael (October 10, 2018). "How Amazon's Higher Wages Could Increase Productivity". Harvard Business Review. ISSN 0017-8012. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Leigh, J. Paul (February 2019). "Arguments for and Against the $15 Minimum Wage for Health Care Workers". American Journal of Public Health. 109 (2): 206–207. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304880. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 6336047. PMID 30649937.

- ^ a b Kinder, Molly (May 28, 2020). "Essential but undervalued: Millions of health care workers aren't getting the pay or respect they deserve in the COVID-19 pandemic". Brookings. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Conradis, Brandon (April 23, 2018). "14 states hit record-low unemployment". TheHill. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ Flows, Capital. "Thanks To 'Fight For $15' Minimum Wage, McDonald's Unveils Job-Replacing Self-Service Kiosks Nationwide". Forbes. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ "Minimum Wages in canada : theory, evidence and policy". Hrsdc.gc.ca. March 7, 2008. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ^ a b Chappell, Bill; Wamsley, Laurel (October 2, 2018). "Amazon Sets $15 Minimum Wage For U.S. Employees, Including Temps". NPR. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ Ferenstein, Gregory. "New Study Suggests Minimum Wage Leads To Automation Of Low-Skill Workers". Forbes. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ Kelly, Gavin. "SeaTac: the small US town that sparked a new movement against low wages", The Guardian, February 22, 2014.

- ^ Rosenblum, Jonathan (March 14, 2017). Beyond $15: Immigrant Workers, Faith Activists, and the Revival of the Labor Movement. Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-9812-7.

- ^ DePillis, Lydia. "Seattle is a guinea pig for $15 minimum wage. Here's what the latest research shows", CNN, October 23, 2018.

- ^ Dillon, Liam and John Myers. "Gov. Brown hails deal to raise minimum wage to $15 as 'matter of economic justice'", Los Angeles Times, March 28, 2016.

- ^ "Minimum Wage California, State, Cities, Tribes, Towns: San Francisco, San Diego, Palo Alto, LA, Miwok Indians". Paywizard.org. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ DeCosta-Klipa, Nik. "What you need to know about the 'grand bargain' that Charlie Baker just signed into law", Boston.com, June 28, 2018.

- ^ "$15 Minimum Wage, Required Paid Leave Are Coming To Mass., After Gov. Baker Signs 'Grand Bargain'". www.wbur.org. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ "New York State Increases Minimum Wage and Enacts Paid Family Leave", JDSupra.com, April 29, 2016.

- ^ a b Corasaniti, Nick. "In New Jersey, the Minimum Wage Is Set to Rise to $15 an Hour", The New York Times, January 17, 2019.

- ^ Patrick McGeehan (July 22, 2015). "New York Plans $15-an-Hour Minimum Wage for Fast Food Workers". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ^ Lathrop, Yannet; Lester, T. William; Wilson, Matthew (July 27, 2021). "Quantifying the Impact of the Fight for $15: $150 Billion in Raises for 26 Million Workers, With $76 Billion Going to Workers of Color". National Employment Law Project. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- ^ Jones, Sarah (December 1, 2018). "For Low-Wage Workers, the Fight For 15 Movement Has Been a Boon". Intelligencer. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ Minimum wage loophole written to help labor unions, Washington Examiner, December 24, 2014.

- ^ Morath, Eric; Duehren, Andrew (February 8, 2021). "$15 Minimum Wage Would Cut Employment, Reduce Poverty, CBO Study Finds - Nonpartisan study says raising minimum wage would cost 1.4 million jobs but lift 900,000 people above the poverty line". Wall Street Journal.

While many Americans would see raises, the analysis showed a minimum-wage increase would cause prices to rise, the federal budget deficit to widen and overall economic output to slightly decrease over the next decade. ... Higher wages would increase the cost of producing goods and services, and businesses would pass some of those increased costs on to consumers in the form of higher prices, resulting in reduced demand, the CBO said. 'Employers would consequently produce fewer goods and services, and as a result, they would tend to reduce their employment of workers at all wage levels,' the report said. 'Young, less educated people would account for a disproportionate share of those reductions in employment.'

- ^ Reich, Michael (February 1, 2021). "Effect of a Federal Minimum Wage Increase to $15 by 2025 on the Federal Budget". Institute for Research on Labor and Employment.

- ^ Dube, Arindrajit (February 24, 2021). "No, a $15 minimum wage won't cost 1.4 million jobs". Washington Post.

That's how it arrives at the figure of 1.4 million lost jobs. Based on my own review of the overall evidence but still following CBO's approach, I would estimate that a national minimum wage increase to $15 per hour would lead to job losses under 500,000.

- ^ Dube, Arindrajit (2019). Impacts of minimum wages: review of the international evidence. London: HM Treasury. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-912809-89-9.

Further reading

[edit]- "QSR employees call for national day of strikes over wages". QSRweb. August 19, 2013. Archived from the original on October 6, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Shields, Annie (May 8, 2013). "Fast Food Workers Strike in St. Louis". The Nation. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Fox, Emily Jane (April 4, 2013). "New York McDonald's, Domino's Pizza workers strike". CNN. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Aronowitz, Nona Willis (December 11, 2012). "Why Most Walmart and Fast Food Workers Didn't Strike". The Nation. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Robert Reich on the Fast Food Strike and Obama's Inequality Speech. Moyers & Company. December 5, 2013.

- Moberg, David (December 6, 2013). A Death Knell for the McJob? Archived December 9, 2013, at the Wayback Machine In These Times. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- Berman, Jillian (December 12, 2013). Telling Fast Food Workers To 'Get A Better Job' Is Nonsense, In 1 Chart. The Huffington Post. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- Marie Rantzau, Louise (May 15, 2014). I'm making $21 an hour at McDonald's. Why aren't you? Reuters. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- Criticism of fast food

- 2012 labor disputes and strikes

- 2013 labor disputes and strikes

- 2014 labor disputes and strikes

- 2015 labor disputes and strikes

- Foodservice strikes

- Labor disputes in California

- Labor disputes in New York City

- Labor disputes in Michigan

- Labor disputes in Minnesota

- Labor disputes in Missouri

- Labor disputes in Washington (state)

- Labor disputes in Washington, D.C.