Þrymskviða

Þrymskviða (Þrym's Poem;[1][2] the name can be anglicised as Thrymskviða, Thrymskvitha, Thrymskvidha or Thrymskvida) is one of the best known poems from the Poetic Edda. The Norse myth had enduring popularity in Scandinavia and continued to be told and sung in several forms until the 19th century.

Synopsis

[edit]In the poem Þrymskviða, Thor wakes and finds that his powerful hammer, Mjöllnir, is missing. Thor turns to Loki first, and tells him that nobody knows that the hammer has been stolen. The two then go to the court[4] of the goddess Freyja, and Thor asks her if he may borrow her feather cloak so that he may attempt to find Mjöllnir. Freyja agrees, saying she would lend it even if it were made of silver and gold, and Loki flies off, the feather cloak whistling.

In Jötunheimr, the jötunn lord Þrymr sits on a burial mound, plaiting golden collars for his female dogs, and trimming the manes of his horses. Þrymr sees Loki, and asks what could be amiss among the Æsir and the Elves; why is Loki alone in the Jötunheimr? Loki responds that he has bad news for both the elves and the Æsir: that Thor's hammer, Mjöllnir, was gone. Þrymr says that he has hidden Mjöllnir eight leagues beneath the earth, from which it will be retrieved if Freyja is brought to marry him. Loki flies off, the feather cloak whistling, away from Jötunheimr and back to the court of the gods.

Thor asks Loki if his efforts were successful, and that Loki should tell him while he is still in the air as "tales often escape a sitting man, and the man lying down often barks out lies".[5] Loki states that it was indeed an effort, and also a success, for he has discovered that Þrymr has the hammer, but that it cannot be retrieved unless Freyja is brought to marry Þrymr. The two return to Freyja, and tell her to dress herself in a bridal head dress, as they will drive her to Jötunheimr. Freyja, indignant and angry, goes into a rage, causing all of the halls of the Æsir to tremble in her anger, and her necklace, the famed Brísingamen,[a] flies off of her.[b] Freyja flatly refuses, saying that if she did (allow herself to mate a jötunn) that would make her the most man-crazed wench around.[c]

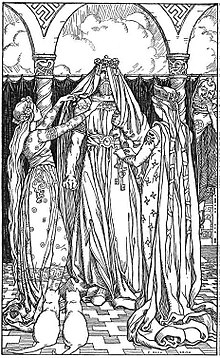

As a result, the gods and goddesses meet and hold a Thing (Assembly)[d] to discuss and debate the matter. At the Thing, the god Heimdallr puts forth the suggestion that, in place of Freyja, Thor should be dressed as the bride, complete with jewels, women's clothing down to his knees, a bridal head-dress, and the necklace[10] (or neck-ring[13]) Brísingamen (and, arguably, another lower necklace covering the breast, though this is contested[17]). Thor comments he would be ridiculed as a sissy[20]) if he submits to the idea, but Loki (here described as "son of Laufey"[e]) dissuades him saying that this will be the only way to get back Mjöllnir, and without Mjöllnir, the jötnar will overtake Asgard. The gods dress Thor as a bride, and Loki states that he will go with Thor as his handmaiden (or bridesmaid), and that the two shall drive to Jötunheimr together.

After riding together in Thor's goat-driven chariot, the two, disguised, arrive in Jötunheimr.[f] Þrymr commands the jötnar in his hall to spread straw on the benches, for Freyja has arrived to marry him. Þrymr recounts his treasured animals and treasures including many necklaces[g], stating that Freyja was all that he was missing in his wealth.[21]

Early in the evening, the disguised Loki and Thor meet with Þrymr and the assembled jötnar. Thor eats and drinks ferociously, consuming entire animals and three casks of mead. Þrymr finds the behaviour at odds with his impression of Freyja, and Loki sitting there like a "very shrewd maid",[h] invents the excuse that "Freyja's" behaviour is due to her having not consumed anything for eight entire days before arriving due to her eagerness to arrive. Þrymr then lifts "Freyja's" veil and wants to kiss "her" until catching the terrifying eyes staring back at him, seemingly burning with fire. Loki states that this is because "Freyja" had not slept for eight nights in her eagerness.

The "wretched sister" of the jötnar appears, asks for gold [arm-]rings as bridal gifts from "Freyja", and the jötnar bring out Mjöllnir to "sanctify the bride", to lay it on her lap, and marry the two by "the hand" of the goddess Vár. Thor laughs internally when he sees the hammer, takes hold of it, strikes Þrymr, beats all of the jötnar, and kills the "older sister" of the jötnar.[22][23][24][25]

Dating

[edit]There is no agreement among scholars on the age of Þrymskviða. Some have seen it as thoroughly heathen and among the oldest of the Eddaic poems, dating it to 900 AD.[26][27][28] but this view is now in the minority.[29]

A number of scholars, on the other hand, dates the poem to the first half of the 13th century,[30] and collectively they have advanced four main reasons for the younger dating.[31] Jan de Vries characterized the work to be a Christian-era parody of the heathen gods.[32][33]

One basis of the older dating is the archaic language, in particular, the heavy use of the of/af particle,[34] which is not addressed by some supporters of later dating, such as the Swedish scholar Peter Hallberg.[35] Finnur Jónsson also argued there were some died-out pagan customs preserved in the poem, for example, the necklaces of the type hanging to the chest[i] were no longer in style by the Christian era.[15]

Analysis

[edit]The storyline is a prime example of the folktale motif ATU 1198b "The Theft of the Thunder-Instrument" (or "Thunder's Instrument"),[36] and also incorporates ATU 403c "The Substituted Bride".[37]

In other tales, Loki's explanations for Thor's behavior has its clearest analogies in the tale Little Red Riding Hood, where the wolf provides equally odd explanations for its differences from the grandmother than Little Red Riding Hood was expecting.[38]

Balladry

[edit]There are versions of the story in ballad-form, composed during the medieval (or post-medieval) periods, in Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, and Icelandic.[39][40][42] These are catalogued as TSB type E 126:[43] i.e., the Danish Tord af Havsgaard (DgF 1), Swedish Tors hammarhämmtning (SMB 212[44]), Norwegian Torekall (NMB 188),[43] and the Icelandic rímur cycle Þrymlur (c. 1350–1450).[j][37]

Danish

[edit]The various known redactions of the Danish ballad Tord af Havsgård (DgF 1) are subdivided into variant types 1A B Ca–c.[46]

Version A has been translated as "Thor of Asgard" by Prior (1860), and as "Thord of Hafsgaard" by E. M. Smith-Dampier (1914).[43] In Ballad 1A, "Tord af Havsgård" (tr. "Thord of Hafsgaard")[k] the title hero is riding over the green meadow, having lost his gold hammer for a long while, and the ballad proclaims (in the emended reading) "so a man shall win a shrew (wildwoman)", explained by commentators as a jocular hint of Tord himself (or his "old father"[48]) later having to dress up as a bride.[50][53]

Tord tells his brother Lokke Leymand (or "Jester"[l]) to go to Nørrefjeld (tr. "Norrefield", "Northland") to seek the hammer, and Lokke wears the fjederham ("feather-skin") to fly there to the "tossegreven"(=Troldkongen,[48] tr. "Giant-King").[m] The Giant-King reveals he has hidden the hammer 55 fathoms (15 and 40 fathoms) deep in the earth and will not return it, unless Tord and Lokke relinquish their sister (Fredens-borgh [sic.], normalized as Freiensborg, tr. "Fredensborg") to become the giant's wife. When Lokke brings home this proposition, his proud sister springs up from the bench and replies, "Give me away to a Christian man, not some loathely troll",[n] and she suggests they brush up the hair of "our old father" and pass him off as a maiden to send to Nørrefjeld.[o] Although one should expect her to say "our brother", it is clarified by commentators that "Old Father" is a commonplace nickname for a thunder deity,[p] hence, Tord is really meant here as the person being dressed up as bride.[57][47] There is a banquet, and as in the Eddic version, the cross-dressed bride shows enormous appetite devouring a whole ox and other foods.[59][q] The appetite raises the giant's suspicion and Lokke delivers an excuse (quite similar to the one in the Eddic poem). Now 8 champions bring the hammer borne on a tree, and places it on the bride's knee; Tord wields the hammer as if it were a wand, and slays the "tossegreven" (Giant-King).[60][61][47][62]

Swedish

[edit]The Swedish ballad was recorded in the 17th century.[65] In the Swedish ballad (version Ab, normalized spelling), Thor is called Torkar,[r] Loki is called Locke Lewe,[s] Freyja is called Frojenborg and Þrymr is called Trolletram.[69][t]

While in the Danish Ballad the three god figures are presented as siblings, in the Swedish version, this relationship is removed or obfuscated. Torkar addresses Locke as "legodrängen min" (st. 2),[71] meaning my "hired servant".[72][u][v] And the "maiden Frojenborg" ("Swedish: jungfru Frojenborg", st. 6)[75] is demanded (see below), instead of "your sister" (Danish: jer søster, C ver., st. 7).[71]

Trolletram has buried Torkar's hammer "fifteen fathoms and forty"[w] in the ground, and tells Locke to take the answer back to Torkar that "His hammer he ne'er will see, / Until he sends may Fröyenborg.. to me",[49] i.e., the "maiden Frojenborg".

Norwegian

[edit]The Norwegian version Torekall[x] has been translated into English under the title "Thorekarl of Asgarth".[77]

Opera

[edit]The first full-length Icelandic opera, Jón Ásgeirsson's Þrymskviða, was premiered at Iceland's National Theater in 1974. The libretto is based on the text of the poem Þrymskviða, but also incorporates material from several other Eddic poems.[78]

Icelandic statue

[edit]

A seated bronze statue of Thor (about 6.4 cm) known as the Eyrarland statue from about AD 1000 was recovered at a farm near Akureyri, Iceland and is a featured display at the National Museum of Iceland. Thor is holding Mjöllnir, sculpted in the typically Icelandic cross-like shape. It has been suggested that the statue is related to a scene from Þrymskviða where Thor recovers his hammer while seated by grasping it with both hands during the wedding ceremony.[79]

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Finnur ed. (1926) st. 13, " men Brísinga"; Larrington (1999), st. 13, "necklace of the Brisings"; her endnote states that the necklace is frequently associated with the goddess but "we know little more about it".

- ^ Finnur ed. (1926) st. 13, "stökk>stökkva" glossed as 'leap, spring', and Thorpe gives "flew the famed Brisinga necklace", though Larrington renders as "necklace of the Brisings fell from her".

- ^ Finnur ed. (1926) st. 13, verða vergjarnasta in which can be recognized the elements verr 'man' and gjarn 'eager, willing'; hence the term vergjarnasta is literally 'most crazy for men',[6] which Larry rendered as "the most sex-crazed of women".[7] though various sources use "maddest for men"[8]

- ^ Finnur ed. (1926) st. 14, " allir á Þingi"; Larrington (1999), st. 14, "came to the Assembly".

- ^ Finnur ed. (1926) st. 18; Larrington (1999), st. 18.

- ^ Finnur ed. (1926) st. 22. hafrar, pl. of hafr 'buck goat', Larrington (1999), st. 21. The goats's names are not explicitly given.

- ^ Or "neck-rings" (Orchard tr.); ON menja, pl. of men, already explained in note above.

- ^ Finnur ed. (1926) st. 28 "alsnotra ambótt (ambátt)"; Larrington (1999), st. 26.

- ^ As already discussed, Finnur thinks this was a störvi (necklace) and different from the Brisings' men (neck-ring)

- ^ Syndergaard (1995) does not list it since it was untranslated at that time. Colwill and Haukur Þorgeirsson's edition with English translation appeared in 2020.[45]

- ^ Havsgård might be construed as "Sea-Court".[47]

- ^ The variant reading "Lokke Leimand" where Leimand/Lejmand means "Jester" according to Finnur Magnússon's Edda which glossed the word (in Latin) as "joculator vel musicus"[54] Finnur's edition digested in (FQR, reviewer apparently was Keightley), and gives the meaning of the word Lejmand as "Juggler".[49] The variant reading "Lokke Leimand" Str. 3 (also Str. 9, 23) is used in Bugge&Moe's normalized text, emended from Gruntvig's redaction of "liden Locke", with variant reading of "Lochy Leymandt" in version Ab footnoted. This "Lokke Leimand" is considered to be a corruption of "Loki" being "Laufeyar sonr".[55][47]

- ^ This Danish word tosse pointed out to be a cognate of þurs,[47] syn. jötunn (giant).

- ^ Danish led 'disgusting' is cognate with English loath. Smith-Dampier uses "goblin grim", while Schweitzer seems to skip the adjective.

- ^ The text at 13, 4 "for en saa stalt iomfru" is emended to "for [en sa væn en mår]" by Bugge & Moe using the C-version text, to preserve the rhyme with hår for 'hair', but this mår ('marten') may be a later corruption, and they explore the possibility that the bride name Solentå from another ballad may be applicable here.[56]

- ^ According to Bugge, in Jämtland "Fader Toren (father Tore)" is a reference to the thunder god Thor (cf. notes to Swedish "Torkar", Norwegian "Torekall" below); he also mentions such nicknaming also occur in Estonian, Lettish, and Finnish culture.

- ^ The fake bride also ate 30 (var. 15) salted pork (or Speck, according to Schweitzer), 700 bread, and 12 tuns of ale (Smith-Dampier "wine"; Schweitzer: Bier). The food fare described in strophes 16 and 17 which are somewhat repetitive, and Schweitzer omits Str. 16.

- ^ "Tor-kar" can be construed in Danish as Tor-gubben,[66] or in English "Oldman-Thor".[67] But the term kar meaning "old man" in Swedish is apparently not attested in Danish, hence, the Swedish lore may have influenced the Danish ballad.[55]

- ^ Here Lewe is thought to be a corruption of Old Icelandic lævísi (lævíss) meaning 'crafty", according to Finnur Magnússon's Edda.[54][68]

- ^ The names in version Aa are spelt differently: "Tårckar", "Locke Loye", "Floyenborg", but "Trolletram" is the same.[63] This more or less matches the names in the partial English Foreign Quarterly Review 4 (attr. to Thomas Keightley) which gives "Tår-Kar", "Lockë", "Fröyenborg" and the adversary as "Trollë-Tram",[49] digested from the treatment of these ballads in Finnur Magnùsson's Edda[70]

- ^ Whereas in the Danish Ballad (ver. A, st. 2) Tord speaks to "his brother" (Danish: broder sin Lokke[73]

- ^ This calling Locke a "servant" is explained as an echo of Loki being called "Ódinn's servant" in Þrymlur, Lokrur, and Sörla þáttr.[74]

- ^ Swedish: femton famnar och fyratio (st. 5), though [mis-]translated as "fifteen fathoms and fourteen".[49]

- ^ This is also equivalent to Old Norse "Þórr karl" or "Thor (old) man".[76]

References

[edit]- Citions

- ^ Britt-Mari Näsström (2013). "Old Norse Religion". In Christensen, Lisbeth Bredholt; Hammer, Olav; Warburton, David (eds.). The Handbook of Religions in Ancient Europe. Durham: Acumen Publishing. pp. 324–337. ISBN 9781844657100.

- ^ Quinn, Judy; Cipolla, Adele (2016). Studies in the Transmission and Reception of Old Norse Literature: The Hyperborean Muse in European Culture. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. ISBN 978-2-503-55553-9.

- ^ Cleasby-Vigfusson, s.v. "tún".

- ^ Old Norse: tún, glossed as 'town', or 'hedged enclosure, homestead'[3] A few strophes down, Æsir's Old Norse: garðar is mentioned, which is the plural of garðr 'yard', 'courtyard, court' etc. The two terms tún and garðar are both rendered as "court[s]" by Larrington, and "dwelling[s]" by Thorpe.

- ^ Larrington (1999), st. 10

- ^ Clunies Ross (2002), p. 193 (endnote 6)

- ^ Larrington (1999), st. 13

- ^ Jón Hnefill Aðalsteinsson (1998); Orchard, Andy (2011), etc.

- ^ Cleasby-Vigfusson, s.v. "men"

- ^ Finnur ed. (1926) st. 19 "meni Brísinga", dative of men glossed as "necklace",[9] hence Larrington tr, "necklace of the Brisings".

- ^ Orchard, Andrew (2022). "Thor". Dictionary of Norse Myth & Legend. Orion. ISBN 9781399601429.

- ^ "Song of Thrym". The Elder Edda. Translated by Orchard, Andrew. Penguin UK. 2013. ISBN 9780141393735.

- ^ Orchard's translation gives "Brisings' neck-ring" and "broad gems sitting on his chest" as items for Thor to wear.[11][12]

- ^ Cleasby-Vigfusson, Icelandic-English Dictionary, s.v. "sörvi"

- ^ a b Finnur Jónsson (1920), p. 166.

- ^ Frank, Roberta (1970). "Onomastic play in Kormakr's verse: The name Steingerðr". Mediaeval Scandinavia. 3: 26n36.

- ^ Finnur Jónsson insisted that the men goes only around the neck, so that the unnamed gemmed accessory adorning Freyja-Thor's chest must have been a different sort of jewelry, and it would have been called a steinsörvi (cf. sörvi[14]), made of strung up amber and glass beads.[15] However, linguist Roberta Frank has later asserted that the Brísingamen was in fact a steinsörvi type necklace.[16]

- ^ Cleasby-Vigfusson, s.v. "argr".

- ^ Clunies Ross (2002), pp. 194 (endnote 16)

- ^ Finnur ed. (1926) st. 17 "argan">argr" glossed 'emasculate, effeminate';[18] Larrington renders as "pervert"; Clunies Ross as "unmanly" and as "sexually perverse", the latter elaborated more explicitly as "passive partner in a homosexual relationship".[19]

- ^ Finnur ed. (1926) st. 23–24; Larrington (1999), st. 22–23.

- ^ Finnur ed. (1926), pp. 131–140 In 34 st.

- ^ Larrington, Carolyne (Trans.) (1999) [1996]. "Thrym's Poem". The Poetic Edda. Oxford World's Classics. pp. 97–101. ISBN 0-19-283946-2. In 32 st.

- ^ Thorpe, Benjamin (Trans.) (1906). "The Lay of Thrym, or the Hammer Recovered". In Anderson, Rasmus B.; Buel, J. W. (eds.). The Elder Eddas of Saemund Sigfusson. New York: Norrœna Society. pp. 53–57. In 39 st.

- ^ Finnur Jónsson (1920), pp. 162–163.

- ^ Gordon, E. V. (1957) An Introduction to Old Norse, p. 135 apud Barnes (1999), p. 111

- ^ Finnur Jónsson (1920), p. 166 dated it to after 875

- ^ More recently, Einar Ólafur Sveinsson; Jónas Kristjánsson cited by McKinnell (2014), p. 200

- ^ Barnes (1999), p. 111: ""Few scholars would now accept E.V. Gordon's view.. [it was] 'composed about 900'"

- ^ de Vries, Hallberg (1954), Hallvard Magerøy (1958), Reinert Kvillerud (1965) and Alfred Jakobsen (1984), cited by McKinnell (2014), p. 200

- ^ McKinnell (2014), pp. 200ff.

- ^ De Vries, Jan (2008) [First published 1938]. Boon-de Vries, Aleid; Huisman, J. A. (eds.). Edda - Goden- en heldenliederen uit de Germaanse oudheid. Deventer, Netherlands: Ankh-Hermes bv. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-90-202-4878-4.

- ^ Cf. Clunies Ross (2002), pp. 182–184 on the assessment of whether this line of reasoning (a comic burlesque or parody treatment must necessarily have occurred in the Christianized era, as late as 13th century).

- ^ McKinnell (2014), p. 200.

- ^ Hallberg, Peter (1954). "Om Þrymskviða" Arkiv för nordisk filologi 69. pp. 51–77, apud Barnes (1999), p. 113

- ^ Frog (2018), pp. 137, 147.

- ^ a b McGillivray, Andrew (2023). "(Review) The Bearded Bride: A Critical Edition of Þrymlur. 2020. Edited and translated by Lee Colwill and Haukur Þorgeirsson. Viking Society for Northern Research, University College". Scandinavian-Canadian Studies. 30: 1–4.

- ^ Iona and Peter Opie, The Classic Fairy Tales, p. 93-4 ISBN 0-19-211559-6.

- ^ Larrington (1999), p. 97 notes "number of.. Danish and Swedish ballads".

- ^ Bugge & Moe (1897), pp. 16–25 tabulates the texts of the Norwegian, Swedish, Danish A and Danish C versions of the ballad.

- ^ a b Arwidsson, Adolf Iwar, ed. (1834). "1. Hammar-Hemtningen". Svenska fornsånger (in Swedish). Vol. 1. Stockholm: P. A. Norsted & Söner. pp. 3–6, 7–9.

- ^ Finnur Jónsson (1920), p. 166 held the view that Þrymskviða "cannot be said to have been written in Iceland, and it must be Norwegian"; and suggests Norwegian folk song were derived in the Middle Ages. He names the Norwegian (Tore Kals vise) and Danish ballads (Tord af Havsgård) and notes the Swedish ballad to have been printed by Arwidsson[41] (and by Bugge & Moe). On the Icelandic Þrymlur (c. 1400), Finnur contests Bugge & Moe (1897), p. 78's assessment that the Swedish ballad derived from this Icelandic version.

- ^ a b c Syndergaard, Larry E. (1995). "Tord von Hassgardt". English Translations of the Scandinavian Medieval Ballads: An Analytical Guide and Bibliography. Nordic Institute of Folklore. ISBN 9529724160.

- ^ a b Jonsson, Jersild & Jansson (2001), pp. 85–86.

- ^ Colwill, Lee; Haukur Þorgeirsson edd. trr. (2020). The Bearded Bride: a critical edition of Þrymlur. London: Viking Society for Northern Research, University College London.

- ^ Grundtvig, Svend (1976) Danmarks gamle folkeviser 12: 40. Volume 1 of the compilation included only 1A B(Grundtvig (1853), 1:1–7, 23 st. and 27 st., respectively), Volume 4 supplemented the C version (Grundtvig & Olrik (1883), 4:580–582, 25 st.).

- ^ a b c d e f Schweitzer, Philipp [in German] (1888). Geschichte der skandinavischen Litteratur: Geschichte der Skandinavischen Litteratur von der Reformation bis auf die skandinavische Renaissance im 18. Jahrhundert. Vol. 2. Leipzig: Wilhelm Friedrich. pp. 31–32.

- ^ a b Bugge & Moe (1897), p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f Anonymous (attr. Thomas Keightley) (1829). "Om några underarter av ljóðaháttr: bidrag till den fornnorsk-fornisländska" [Scandinavian Mythology]. The Foreign Quarterly Review. 4: 118–120.

- ^ First 3 st. translated in Foreign Quarterly Review 4 (1829), p. 119[49] with no byline but attributed to Thomas Keightley by Syndergaard, and characterized as a "close" translation.

- ^ Bugge & Moe (1897), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Recke (1927), p. 3.

- ^ This emended text recurs in the first and last stanza as refrain, but in the 1A version, the wording is emended by scholars to read "sverken", supposedly a loanword from Old Icelandic svarkr meaning a 'combative woman',[51][52] where the original text has been corrupted to sound like "win Sweden". Schweitzer renders this into German as "Die Stolze" or "the haughty [woman]".[47] Both Smith-Dampier and Thomas Keightley (Foreign Quarterly Review) omit this refrain on the first and last stanzas.

- ^ a b Singned "Sofus Bugge", notes to 1b (1Ab or 1A subtype b), in: Grundtvig & Olrik (1883), 4:579; Bugge & Moe (1897), p. 92, n1

- ^ a b Bugge & Moe (1897), p. 91.

- ^ Bugge & Moe (1897), p. 32.

- ^ Bugge & Moe (1897), p. 90.

- ^ Läffler, Leopold Fredrik Alexander [in Swedish] (1913). "Om några underarter av ljóðaháttr: bidrag till den fornnorsk-fornisländska". Studier i nordisk filologi. 5: vi.

- ^ The 1 ox (in Danish version A) concurs with the Eddic version and Norwegian version, but in another Danish version (C, printed by Bugge&Moe) 7 oxen are consumed,[58] and in Danish B (Vedel's printed version) 15 oxen, which Schweitzer uses also.

- ^ Danish text of DgF 1A given in Grundtvig (1853), '1:3–4; 1A and 1C are printed side-by-side in reprinted in normalized spelling by Bugge & Moe (1897), pp. 17, 19, 21, 23, 25. Cf. also reprint in Recke (1927), pp. 3–6.

- ^ Smith-Dampier, E. M., tr. (1914). "Thord of Hafsgaard". More Ballads from the Danish and Original Verses. Andrew Melrose. pp. 8–11.

- ^ Final 5 st. translated in Foreign Quarterly Review 4 (1829), p. 120[49] attributed to Thomas Keightley.

- ^ a b Jonsson, Jersild & Jansson (2001), p. 85.

- ^ Jonsson (1967), p. 278.

- ^ Preserved in manuscript, later scholarship determined it to have been recited by peasant wife Ingierd Gunnarsdotter (1601/1602–1686) and redacted in the 1670s.[63] This person had a reputed repertoire of 300 heroic ballads, of which 58 ballads have been attributed to her by scholarship.[64]

- ^ Bugge & Moe (1897), pp. 90, 89.

- ^ Keightley (1829), p. 119.

- ^ Magnusen (1822), p. 99n.

- ^ Normalized spelling as printed in Bugge & Moe (1897), pp. 16–25, from Arwidsson's base text, which is actually given as version Ab by SMB. There are two versions (Aa and Ab) are copied down in the KB (Royal Library of Sweden) manuscript of ballads. Although SMB gives both as quarto (4º),[44] Arwidsson claims there is a quarto and a later-dated octavo copy, and uses the latter as base text, with the other copy footnoted as "QM".[41] SMB is vice versa, using Aa as base text and Ab only given as footnoted variant readings.

- ^ cf. Magnusen (1822), pp. 98–99, 123–128

- ^ a b Bugge & Moe (1897), p. 16.

- ^ Bugge & Moe (1897), p. 92: "Danish: lejet tjener"

- ^ Bugge & Moe (1897), p. 17.

- ^ Bugge & Moe (1897), p. 92.

- ^ Bugge & Moe (1897), p. 18.

- ^ Bugge & Moe (1897), p. 89.

- ^ Colbert, D. (tr.) in Sven H. Rossel (1982) Scandinavian Ballads, apud Syndergaard (1995)

- ^ Nagy, Peter; Rouyer, Phillippe; Rubin, Don (2013). World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre: Volume 1: Europe. Routledge. p. 461. ISBN 9781136402968.

- ^ Clunies Ross (2002), pp. 188–189.

- Bibliography

- (Primary sources)

- Finnur Jónsson, ed. (1926). "Þrymskviða". Sæmundar-Edda: Eddukvæði (in Icelandic). København: Kostnaðarmaður, Sigurður Kristjánsson. pp. 131–140.

- Grundtvig, Sven, ed. (1853). "1. Tord af Havsgaard". Danmarks gamle folkeviser (in Danish). Vol. 1. København: Samfundet til den danske literaturs fremme. pp. 1–7.

- Grundtvig, Sven; Olrik, Axel, eds. (1883). "Tillæg [til] Nr. 1. Tor af Havsgaard". Danmarks gamle folkeviser (in Danish). Vol. 4. København: Samfundet til den danske literaturs fremme. pp. 578–583.

- Jonsson, Bengt R. [in Swedish]; Jersild, Margareta [in Swedish]; Jansson, Sven-Bertil, eds. (2001). "212 Tors Hammarhämmtning". Sveriges Medeltida Ballader. Svenskt visarkiv. pp. 85–86.

- Magnusen, Finn, ed. (1822). "Qvad om Thrym". Den aeldre Edda: en samling af de nordiske folks aeldste sagn og sange, ved Saemund Sigfussön kaldet hin frode (in Danish). Vol. 2. Kjøbenhavn: Gyldendal. pp. 105–128.

- Recke, Ernst von der [in Danish], ed. (1927). "1. Tord af Havsgaard". Danmarks fornviser: Paa grundlag af "Danmarks gamle folkeviser" (in Danish). Vol. 1. København: Møller & Landschultz. pp. 3–6.

- (Secondary sources)

- Barnes, Michael P. (1999). A New Introduction to Old Norse: Reader. Viking Society for Northern Research, University College.

- Bugge, Sophus; Moe, Moltke (1897). Torsvisen i sin norske Form. Christiania: Centraltrykkeriet.

- Clunies Ross, Margaret (2002). "Reading Þrymskviða". In Acker, Paul; Larrington, Carolyne (eds.). The Poetic Edda: Essays on Old Norse Mythology. London: Routledge. pp. 177–184. ISBN 0-8153-1660-7.

- Finnur Jónsson (1920). Den oldnorske og oldislandske litteraturs historie (in Danish). Vol. 1 (2 ed.). København: G. E. C. Gad. pp. 162–167.

- Frog, Etunimetön (2018). "When Thunder Is Not Thunder; Or, Fits and Starts in the Evolution of Mythology". In Valk, Ülo; Sävborg, Daniel (eds.). Storied and Supernatural Places: Studies in Spatial and Social Dimensions of Folklore and Sagas. Studia Fennica Folkloristica 12. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. pp. 137–4. ISBN 9789522229946.

- Jonsson, Bengt R. [in Swedish] (1967). Svensk balladtradition. I, Balladkällor och balladtyper [With a Summary in English. The Medieval Popular Ballad in Swedish Tradition I]. Svenskt visarkiv.

- McKinnell, John (2014). "8 Myth as Therapy: The Usefulness of Þrymskvida". In Kick, Donata; Shafer, John (eds.). Essays on Eddic Poetry. Studia Fennica Folkloristica 12. University of Toronto Press. pp. 200–220. ISBN 9781442669277.