The New Atalantis

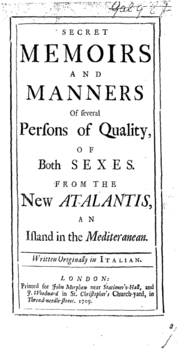

The New Atalantis (full title: Secret Memoirs and Manners of Several Persons of Quality, of both Sexes, From The New Atalantis) was an influential political satire by Delarivier Manley published at the start of the 18th century. In it a parallel is drawn between exploitation of females and political deception of the public.

Sexualising politics

[edit]The New Atalantis appeared in 1709, the first volume in May and the second in October. The novel was initially suppressed on the grounds of its scandalous nature and Manley was arrested and tried, but it was immediately popular and went into seven editions over the following decade. As a political satire on the behaviour of prominent members of the Whig party, it won the approval of the Tory literary faction, among them Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Richard Steele and Jonathan Swift. There is also a reference to its enduring popularity in Alexander Pope's The Rape of the Lock (Canto III.165).

In the immediate background, and influencing the choice of title, was Sir Francis Bacon's novel New Atlantis (1627). In contrast to its altruistic utopianism, Manley reveals a hypocritical dystopia. There was also Thomas Heyrick's long verse satire, The New Atlantis (1687), attacking the defence of Catholicism as espoused by the Tory Party during the Stuart succession crisis of a previous reign. In this case the show of virtue by their Whig opponents is revealed as a sham.

But the work also played its part in the attack on the current political favourite of the Whigs, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, whose wife Sarah was an influential attendant on Queen Anne. Sarah had already served as the target of Manley's earlier satire, The Secret History of Queen Zarah and the Zarazians (1705). Now The New Atalantis was timed to embarrass the Whig party in the coming parliamentary session and was to help the Tories into power in 1710.[1] The relationship between the queen and Sarah Churchill was damaged as a result.

The story concerns the return to earth of the goddess of Justice, Astrea, to gather the information about private and public behaviour necessary for the proper moral education of a prince in her charge. Astrea encounters her mother Virtue, dressed in rags and little regarded, and the two benefit from their power of invisibility to make their observations, guided by the earthy Lady Intelligence. Together they encounter a succession of scenes displaying public and personal corruption, broken lives, ruined virgins, orgies, seductions, and rapes. The narrative employs the framing device of a conversation between the three allegorical female narrators, who observe, report and reflect upon the patterns of life on the remote Mediterranean island which is the scene of their investigations.[2]

The reader's sexual titillation is assisted by the amassing of sensual details in an atmosphere of luxurious accessories, perfumed in the sub-tropical heat, as in the description of the bedroom of Germanicus. Through the windows the scent of jasmine "blew in with a gentle fragrancy. Tuberoses set in pretty gilt and china pots were placed advantageously upon stands; the curtains of the bed drawn back to the canopy, made of yellow velvet, embroidered with white bugles the panels of the chamber looking-glass. Upon the bed were strewed, with a lavish profuseness, plenty of orange and lemon flowers. And to complete the scene, the young Germanicus in a dress and posture not very decent to describe" beguiled the sight of the Duchess who enters and joins him on the bed.

A feminist critic observes that one aspect of the satire addresses the invisibility of women in the masculine world of politics and their consequent ability to influence situations through the power of gossip. The author is thus commenting on her own procedures in order to underline the points she makes. A parallel is also implied in the novel between seduction of the helpless in the sexual arena and deception of the public in the political sphere. Feminine marginalisation is made the image of the general public's political marginalisation.[3]

Supposed details of the author's personal history appeared integrated in the Atalantic world with the story of "Delia" in Volume two, and this was followed up by her autobiographical Adventures of Rivella (1714). Two volumes published in 1710, The Memoirs of Europe, were (in the early 18th century) often referred to as volumes three and four of the Atalantis, although they did not share the fictional setting.

References

[edit]- ^ Soňa Nováková

- ^ Archived online

- ^ Soňa Nováková

Sources

[edit]- Anderson, Paul Bunyan, "Delariviere Manley's Prose Fiction", Philological Quarterley, 13 (1934), p. 168-88.

- Anderson, Paul Bunyan, "Mistress Delarivière Manley's Biography", Modern Philology, 33 (1936), p. 261-78.

- Carnell, Rachel, A Political Biography of Delarivier Manley (London, 2008).

- Needham, Gwendolyn, "Mary de la Rivière Manley, Tory Defender", Huntington Library Quarterley, 12 (1948/49), p. 255-89.

- Needham, Gwendolyn, "Mrs Manley. An Eighteenth-Century Wife of Bath", Huntington Library Quarterley, 14 (1950/51), p. 259-85.

- Köster, Patricia, "Delariviere Manley and the DNB. A Cautionary Tale about Following Black Sheep with a Challenge to Cataloguers", Eighteenth-Century Live, 3 (1977), p. 106-11.

- Morgan, Fidelis, A Woman of No Character. An Autobiography of Mrs. Manley (London, 1986).

- Nováková, Soňa, pp.121-6 "Sex and Politics: Delarivier Manley's New Atalantis"

- Todd, Janet, "Life after Sex: The Fictional Autobiography of Delarivier Manley", Women's Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 15 (1988), p. 43-55.

- Todd, Janet (ed.), "Manley, Delarivier." British Women Writers: A Critical Reference Guide. London: Routledge, 1989. 436–440.

- Gallagher, Catharine, "Political Crimes and Fictional Alibis. The Case of Delarivier Manley", Eighteenth Century Studies, 23 (1990), p. 502-21.

- Ballaster, Rosalind, "Introduction" to: Manley, Delariviere, New Atalantis, ed. R. Ballaster (London, 1992), p.v-xxi.

- Simons, Olaf, Marteaus Europa oder Der Roman, bevor er Literatur wurde (Amsterdam/ Atlanta: Rodopi, 2001), p. 173-179 on contemporary reviews, p. 218-246 on her Atalantis.