SS United States

SS United States at sea in the 1950s

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | United States |

| Owner | United States Lines |

| Operator | United States Lines |

| Port of registry | New York City |

| Route | New York – Le Havre – Southampton (also Bremerhaven) |

| Ordered | 1949[3] |

| Builder | Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company[3] |

| Cost | $79.4 million ($748 million in 2023[5]) |

| Yard number | Hull 488[2] |

| Laid down | February 8, 1950 |

| Launched | June 23, 1951[1] |

| Christened | June 23, 1951[1] |

| Maiden voyage | July 3, 1952 |

| In service | 1952 |

| Out of service | November 14, 1969[4] |

| Identification |

|

| Owner | Various |

| Acquired | 1978 |

| Notes | Multiple owners since 1978[6] |

| Owner | SS United States Conservancy |

| Acquired | February 1, 2011 |

| Status | Laid up in Philadelphia[7] |

| Notes | Continual fundraising since 2011 for conservation.[7] |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage | 53,329 GRT, 29,475 NRT |

| Displacement |

|

| Length |

|

| Beam | 101.5 ft (30.9 m) maximum |

| Draft |

|

| Depth | 175 ft (53 m) (keel to funnel)[8] |

| Decks | 12 |

| Installed power | |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed |

|

| Capacity | 1,928 passengers |

| Crew | 900 |

SS United States (Steamship) | |

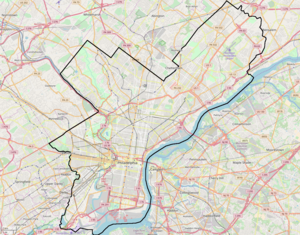

| Location | Pier 82, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Coordinates | 39°55′06″N 75°08′11″W / 39.91833°N 75.13639°W |

| Architect | William Francis Gibbs |

| NRHP reference No. | 99000609[9] |

| Added to NRHP | June 3, 1999 |

SS United States is a retired ocean liner built between 1950 and 1951 for United States Lines. She is the largest ocean liner constructed entirely in the United States and the fastest ocean liner to cross the Atlantic in either direction, retaining the Blue Riband for the highest average speed since her maiden voyage in 1952, a title she still holds.

The ship was designed by American naval architect William Francis Gibbs and could have been converted into a troopship if required by the Navy in time of war. The ship served as an icon for the nation, transporting numerous celebrities throughout her career between 1952 and 1969. Her design included innovations in steam propulsion, hull form, fire safety, and damage control.

Following a financial collapse of United States Lines, she was withdrawn from service in a surprise announcement. The ship has been sold several times since the 1970s, with each new owner trying unsuccessfully to make the liner profitable. Eventually, the ship's fittings were sold at auction, leaving her stripped by 1994. Two years later, she was towed to Philadelphia, where she has remained.

Since 2009, the 'SS United States Conservancy' has been raising funds to save the ship. The group purchased her in 2011 and has drawn up several unrealized plans to restore the ship, one of which included turning the ship into a multi-purpose waterfront complex. In 2015, as its funds dwindled, the group began accepting bids to scrap the ship; however, sufficient donations came in via extended fundraising. Donations have kept the ship berthed at her Philadelphia dock while the group continues to further investigate restoration plans. The ship has been ordered to leave her pier by September 2024 by a judge due to a rent dispute. Currently, her fate is unknown as the conservatory has just months to move the ship.

Design and construction[edit]

Designed by American naval architect and marine engineer William Francis Gibbs, the liner's construction was a joint effort by the United States Navy and United States Lines (USL). The US government underwrote almost 70% of the US$79.4 million construction cost,[3] with the ship's prospective operators, USL, contributing the remaining $28 million.[10]

The vessel was constructed between 1950 and 1952 at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company in Newport News, Virginia.[3] United States was built to exacting Navy specifications, which required that the ship be heavily compartmentalized, and have separate engine rooms to optimize wartime survivability.[11] A large part of the construction was prefabricated, with the hull comprising 183,000 pieces.[12]

Propulsion[edit]

The powerplant of the ship was developed with unusual cooperation with the Navy, leading to a militarized design. The ship never used US Navy equipment, instead opting for civilian variants of various military models. The engine room arrangement was similar to large warships such as the Forrestal-class aircraft carriers, with engineering spaces isolated and various redundancies and backups in onboard systems.[13]: 129, 141

In normal service, she could theoretically generate 310,000 pounds of steam per hour, at 925 psi and 975°F using eight US Navy M-type boilers, however they were operated only at 54% of their capacity. The boilers were divided among two engine rooms, four in each. While they were designed by Babcock & Wilcox, the company only manufactured the boilers in the forward engine room. The rest were made by Foster-Wheeler and are located aft.[13]: 129, 132

Steam from the boilers turned four Westinghouse double-redaction[a] geared turbines, each one connected to a shaft. Each turbine could generate approximately 60,000 shaft horsepower (shp), or 240,000 shp total. If operating at 100% capacity in wartime conditions, initial designs estimated 266,800 shp from 1,100°F steam at 1145 psi could be generated.[13]: 17, 134

The turbines turned four shafts, each rotating a propellor 18 feet (5.5 metres) in diameter. Owing to the designers' previous military experience, each propeller was made to rotate efficiently in either direction, allowing the ship to efficiently move forward or backwards, and to limit cavitation and vibrations. A key secret of the design was that the two inset propellers were five-bladed, while the outermost two had four. This aspect was one of the key concepts allowing for her high speed. [13]: 138–139

Speed[edit]

The maximum speed attained by United States is disputed, as it was once held as a military secret,[14] and complicated by the alleged leak of a top speed of 43 kn (80 km/h) attained after the first speed trial.[15] For example, The New York Times reported in 1968 that the ship could make 42 kn (78 km/h) at a maximum power output of 240,000 hp (180,000 kW).[16] Other sources, including a paper by John J. McMullen & Associates, placed the ship's highest possible sustained top speed at 35 kn (65 km/h).[17] The liner's top speed was later revealed to be 38.32 kn (70.97 km/h), achieved on its full-power trial run on June 10, 1952.[18][19]

Military application[edit]

During the Second World War, many ocean liners, including Normandie and Queen Mary, were seized or requisitioned and used to transport soldiers between various fronts. Since United States was first developed, the US Navy sponsored her construction so that the fast, large, and American-flagged ship could be used to support a war in a similar way.[3]: 186

Troop transport[edit]

The most promising use of the liner in war would have been as a troop transport. If mobilized, onboard furnishings could have been easily removed to make room for a 14,400-man US Army division. Her size and speed meant that she could rapidly deploy a division anywhere in the world without the need to refuel. [13]: 12 [3]: 215

At the end of the Second World War, the Navy's transport capabilities was drastically reduced. Following the Inchon Landings during the Korean War, the Department of Defense realized it lacked troop transport capacity and requisitioned the 1/3rd complete United States to quickly and cheaply fill part of the deficit. Under Navy control, stateroom bathrooms were to be stripped and large spaces divided to make room for gun mounts, wardrooms, more lifeboats, and equipment required to support the enlarged passenger count. [3]: 240

The ship was requisitioned under Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson, who believed it was cheaper and easier to convert an existing vessel than it was to build one from scratch. Days after the announcement was made, the secretary was relieved and replaced by George Marshall. After meeting with the Chairman of the Maritime Administration, Marshall believed that converting United States would take too long to be of any use during the Korean War. A month after her requisitioning was announced, the Joint Chiefs of Staff reversed the decision and returned her to previously scheduled civilian work.[3]: 241

Hospital ship[edit]

By the 1970s, the US Navy had retired all of its hospital ships. The now-laid up United States was studied for potential conversion in 1983 as her size and speed would allow her to rapidly deploy to address any crisis around the world. Under the name USNS United States, it was planned that she would have a capacity of about 1,600 hospital beds, be fitted with an aft helicopter deck, a bow vertical replenishment deck, and a refurbished interior that would have included up to 23 operating theaters and a full set of specialist rooms comparable to any major hospital on land. The plan was spearheaded by the Department of Defense, who wished that she would be based in the Indian Ocean. However, the Navy believed the plan was too expensive and impractical, opting to take no action on the matter.[20]: 194-196

Interior design[edit]

The interiors were designed by Dorothy Marckwald and Anne Urquhart, the same designers behind the interiors for SS America. The goal was to "create a modern fresh contemporary look that emphasized simplicity over palatial, restrained elegance over glitz and glitter".[21][22] An additional goal of the interiors was to replicate the smooth lines seen on the exterior and visualize the ship's speed.[13]: 93

To achieve the look, the liner was furnished in mid-century modern decor, amplified by plentiful use of black linoleum decking and the silver lining of edges. While visually unique compared to her competition, the simplicity of decorations compared to the expected grandeur of ocean liners saw the interiors described as what would be found on a 'navy transport' by those accustomed to the older style.[13]: 93

Also hired were artists to produce American themed artwork for the public spaces,[23] including Hildreth Meière, Louis Ross, Peter Ostuni, Charles Lin Tissot, William King, Charles Gilbert, Raymond Wendell, Nathaniel Choate, muralist Austin M. Purves, Jr., and sculptor Gwen Lux.[24][failed verification] Interior décor also included a children's playroom designed by Edward Meshekoff.[25] Markwald and Urquhart were also tasked with the challenge of creating interiors that were completely fireproof. This posed an exceptional difficulty when selecting materials, such as those for usually flammable items such as drapes or carpet. [13]: 93

Fire safety[edit]

As a result of various maritime disasters involving fire, including SS Morro Castle and SS Normandie, William Gibbs specified that the ship incorporate the most rigid fire safety standards.[26][27]

To minimize the risk of fire, the designers of United States prescribed using no wood in the ship, aside from the galley's wooden butcher's block. Fittings, including all furniture and fabrics, were custom made in glass, metal, and spun-glass fiber, to ensure compliance with fireproofing guidelines set by the US Navy. Asbestos-laden paneling was used extensively in interior structures and many small items were made of aluminum. The ballroom's grand piano was originally designed to be aluminum, but was made from mahogany and accepted only after a demonstration in which gasoline was poured upon the wood and ignited, without the wood ever catching fire.[28][29]

Art[edit]

The liner was decorated by hundreds of unique art pieces, ranging from sculptures to relief murals and paintings. Aluminum was commonly incorporated into the artworks, allowing pieces to be light, fire proof, and match the black-and-silver color theme. For instance, nearly 200 aluminum sculptures were used in first class stairway, with a large eagle located on the landing of each deck joined by the bird and flower of each state.[13]: 93

Funnels and superstructure[edit]

The primary purpose of a ship’s funnels is to ventilate the vessel’s engine rooms, allowing exhaust to escape. Gibbs believed that funnels also serve to create a unique and iconic character for both the ship and her owners. To create an unforgettable silhouette, Gibbs had the liner topped off with two massive, red-white-and-blue, tear-dropped shaped funnels located midship. Standing at 55 feet (17 m) tall and 60 feet (18 m) wide a piece, they were the largest funnels ever put to sea.[3]: 246–248

The funnel design was a pinnacle of Gibb’s experience from designing the Leviathan, America, and Santa-class liners. To prevent soot from the funnels from coating the deck and passengers, horizontal fins located on each side of the funnels deflected the pollutants away from the ship. During the retrofit of the Leviathan decades earlier, it was discovered that her tall funnels served to compromise the stability of the entire vessel. To avoid this issue on United States, Gibbs decided that the funnels and the entire superstructure would be made out of lightweight aluminum to prevent her from becoming top-heavy and at risk of capsizing. At the time, the ship was the world's largest aluminum construction project and the first major application of aluminum on a ship.[3]: 246–248

The main downside to making the funnels and superstructure out of aluminum was that the metal was extraordinary hard to mold and handle compared to the conventional metals, making the funnel’s fabrication the most complex part of her construction. In addition, special care was needed to prevent galvanic corrosion of the aluminum when welded to the steel decking. While shipyard workers were antagonized by the laborious progress, no problems arose during construction and progress continued as planned. [3]: 246–248

Class system[edit]

A design by Gibbs incorporation was a conventional three-tiered class system for passengers, replicating those found on other classical ocean liners. Each class was segregated, having its own dining rooms, bars, public spaces, services, and recreation areas. Gibbs envisioned having passengers enforce the separation, only intermingling in the gymnasium, pool, and theatre.[13]: 70 The stark and physical class separations, an idea associated with the old world, served in contrast to the overall American theme of the ocean liner as the United States was often seen as a nation removed from the old money and class distinctions of old.[30]

At maximum capacity, the liner could have carried 894 first, 524 cabin, and 554 tourist-class passengers.[13]: 16 During a normal season, a first class ticket would start at $350 ($3,971 in 2024), a cabin ticket $220 ($2,496), and a tourist ticket $165 ($1,872).[31]

First class[edit]

| Tour of first-class spaces in current status | |

|---|---|

First Class passengers were entitled to the best services and locations the ship had to offer, including the grand ballroom, smoking room, first-class dining room, first-class restaurants, observation lounge, main foyer, grand staircase, and promenades. Most of these facilities were located midship, distant from the vibrations and distractions of both the engines and outside.[13]: 59, 64

Suites[edit]

The liner’s famous passengers favored first class due to its prestige, priority service, and spacious cabins. Popularized by the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, the 'Duck Suite' was the most well known stateroom onboard. It was created by combining three first-class staterooms into one singular suite, containing four beds, three bathrooms, two bedrooms and a living room. The name came from the walls, decorated with paintings of various waterfowl. Up to 14 similar suites could be created in a similar way, establishing a level of stateroom even above that a standard first class ticket would fetch.[13]: 59, 64 Tickets for the two-bedroom suites started at $930 ($10,552), aimed at the wealthiest passengers onboard. Much like the 'Duck Suite', these rooms reflected a post-war American standard of living, lacking in intricate details and adorned with natural scenes. All suites were spacious and equipped with dimmed lights, items not seen on any other vessels.[3]: 262

Cabin class[edit]

Cabin class was aimed towards the middle class, striking a key balance between the affordability of tourist and the elegance of first class. Each cabin held four beds and a private bathroom, located primarily aft. While inferior to first class, passengers received service and had access to amenities historically reserved to the highest class on other ocean liners.[13]: 66–67 The food, pool, and theater were shared with first-class passengers, making cabin class ideal for those who wanted the first-class experience without paying first-class rates.[30]

Tourist class[edit]

Cheapest of all tickets, spaces for the tourist class were tucked away to the peripheries of the ship where rocking and noise were most pronounced. These small cabins were shared among passengers, each room containing two bunk beds and simply furnished with little detail. Bathrooms were communal, shared among all cabin class passengers in the same passage. Service from the crew was lacking compared to the others, as this class received the lowest priority. While equivalent to the steerage or third-class on other vessels, these poorest conditions on the United States were noticeably better than what was offered on other vessels.[13]: 68, 70

The class was aimed at those who were unable or unwilling to spend much on a ticket, often booked by immigrants and cheap students.[30]

Gallery of passenger spaces[edit]

-

An onboard stairway, with an aluminum sculpture of the Great Seal of the United States on each landing.[13]: 93

-

The grand ballroom, containing the piano and a dance floor. The space was reserved for first-class passengers.[13]: 60

-

A passenger hallway whose lack of decoration was described as having decor compared to that of a warship.

-

The Cabin-class lounge with Hildreth Meière's mural Mississippi in the background.

-

First-class cabin U 141, showing mid-century modern furnishings and the lack of detail common throughout the ship. Not shown is the cabin's private bath.[32]

History[edit]

Commercial service (1952–1957)[edit]

Maiden voyage[edit]

On her maiden voyage—July 3–7, 1952 —United States broke the eastbound transatlantic speed record that was held by RMS Queen Mary for the previous 14 years by more than 10 hours, making the maiden crossing from the Ambrose lightship at New York Harbor to Bishop Rock off Cornwall, UK in 3 days, 10 hours, 40 minutes at an average speed of 35.59 kn (65.91 km/h; 40.96 mph),[33] thus winning the coveted Blue Riband.[34] On her return voyage United States also broke the westbound transatlantic speed record, also held by Queen Mary, by returning to America in 3 days 12 hours and 12 minutes at an average speed of 34.51 kn (63.91 km/h; 39.71 mph). In New York City her owners were awarded the Hales Trophy, the tangible expression of the Blue Riband competition.[35]

The record was not a reflection of her actual operational speed. Prior to her voyage, many expected a 'race' between the American United States and British Queen Elizabeth for national pride over the Blue Riband. In 1951, Gibbs instructed the crew to, "Under no circumstances...beat the record by very much. Beat it by a reasonable amount, such as 32 knots." He hoped that Cunard Line, operator of Queen Elizabeth, would then develop a slightly faster ship. United States would then soundly beat the intentionally low record, sailing at a much higher speed.[36]

Her record breaking speed was also held back by safety concerns. The line understood that the crew was still inexperienced with their new ship, and ordered them to not take unnecessary risk with extravagant speeds. The memory of Titanic influenced USL's caution, an issue personal to several of its leaders. CEO John Franklin was son of White Star Line's office manager Philip Franklin during the disaster, and company director Vincent Astor lost his father on the ship. So concerned about a potential accident, Franklin had pre-written and sealed a message that was only to be made public if there was a disaster during her voyage. [36]

Later service[edit]

During the 1950s and early 1960s, United States was popular for transatlantic travel, sailing between New York, Southampton and Le Havre, with an occasional additional call at Bremerhaven.[37] She attracted frequent repeat celebrity passengers such as Marilyn Monroe, Judy Garland, Cary Grant, Salvador Dalí, Duke Ellington, and Walt Disney, who featured the ship in the 1962 film Bon Voyage!.[38] An unrecognized celebrity on the ship was Claude Jones, a trombonist who had performed with Ellington. He worked as part of the waitstaff and died on board in 1962.[39]

United States proved exceedingly well as the most popular liner in the North Atlantic, as the ship's fame provided her with a reliable clientele. Such a success, United States Lines (USL) began drafting plans to crate a 'running mate' for the ship. Much like Cunard Line's Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, the idea was to operate two liners in tandem with each other. In 1958, this idea eventually evolved into the SS President Washington, a superliner with a very similar design to United States. President Washington was planned to replacing the aging USL liner America, and was to instead operate on the American West Coast and sail the Pacific. However, the idea failed to fruition as Congress did not allocate any funds to the project.[20]: 169–170

Decline (1957–1969)[edit]

For the first time ever in 1957, piston-powered aircraft carried more passengers across the Atlantic than ocean liners. This trend escalated over the next several years as the advent of jet-propelled airliners provided trans-Atlantic routes that were only hours long, compared to days on the fastest ocean liners. The competition threatened to redirect the customers of USL and other shipping conglomerates, even as the economic threat of aircraft was initially brushed off as a 'fad'.[20]: 167–169

Throughout the 1960s, the liner's reputation was permanently altered during strikes by the 'Masters, Mates, & Pilots' Union. The strikes forced the cancellation of voyages and the re-assignment of passengers. A ticket no longer guaranteed a trip aboard, and both passengers and the company began to grow weary of the spotty service.[20]: 170

Together, the cancellations and competition from airlines slowly drew away customers. In 1960, USL refused to release their yearly passenger count due to how low it had become. The issue further compounded in 1961, when the US Department of Commerce announced the ship would no longer be used to carry US military personnel or their families. It was believed that liners were, "Sitting ducks for Soviet bombers" and that air transport was the better option. The loss of the contract was a major blow to the company, and the stark decline in ridership made it clear change was needed.[20]: 171

To increase ticket sales, USL set out to convert the liner America to a cruise ship, dropping trans-Atlantic service for vacation spots around North America. Similar plans were drafted for United States, with her operating as a cruise ship during the less busy winter seasons. To facilitate her new role, she was to have her cabin-class lounge replaced by a swimming pool and every stateroom fitted with a bathroom to attract vacationers. However, the cash-strapped company was weary of any new projects and soon dropped the idea, as the refit was priced at $15 million. Nevertheless, the new cooperate strategy was joined by a major advertisement campaign. These ads were aimed at reinventing the allure of ocean liners in the age of jet aircraft by showing off the speed, luxury, reputation, or another aspect of United States.[20]: 171

By 1961, conditions had not improved. For the first time, a voyage was canceled as only 350 people bought tickets. The US Government was subsidizing USL under the condition that trans-Atlantic service must be maintained, no matter the profitability. After enough pressure from the company, the rule was repealed. With USL now able to set unique itineraries, and hoping to cash into a new market, United States made her first cruises in the Caribbean the next year. These vacations sailed from New York and docked in Nassau, St. Thomas, Trinidad, Curaçao, and Cristobal. She was the largest ship in the region and operated with a temporary pool on her aft deck and no tourist-class passengers.[20]: 172–173

Despite the new itinerary, she was the most expensive liner to operate and was further losing passengers to newer ships such as France. By 1963, anxiety about her future reached crew members and corporate leaders alike, with many unsure of how long the ship would be left in service. Two years later, another strike forced the cancellation of all summer voyages, losing the ship 9,000 passengers and the company $3 million.[20]: 178–179

In 1968, the Atlantic liner routes were dying, with only United States, France, and Queen Elizabeth conducting sailings. To distinguish herself from the competition, she began offering much longer voyages to distant ports in Europe, Africa, and South America. She once again became the most popular ship in the Atlantic, but USL was bought out in 1968. Her new owner was Walter Kidd & Co, who believed the age of ocean liners had passed. Making matters worse, government subsides for the ship were curtailed as there were not enough passengers to justify the cost.[20]: 175–177

As staffing costs/union dues increased, government subsidies decreased, a rise in alleged corporate mismanagement, and passenger un-interest, the ship was overdue for retirement. On 25 October, United States returned from her 400th voyage. After arriving, she was ordered to start a scheduled yearly overhaul in Newport News early. This move canceled a planned 21-day cruise, although bookings were still being made for future voyages.[20]: 178–179

Layup in Virginia (1969–1996)[edit]

After her last voyage, she sailed to Newport News for her scheduled annual overhaul. While there, USL announced its decision to withdraw her from service on November 11th. The partially finished paint coating on the funnels can still be faintly seen. The ship was sealed up, with all furniture, fittings, and crew uniforms left in place. Her funnels were left half-painted when work suddenly halted, which can still be seen today.[27] While many saw her layup as a looming inevitability, the decision came as a surprise to passengers and crew. With no warning, newly unemployed crewmembers had only a few days to finalize work while passengers' already awaiting baggage was loaded onto the Leonardo Da Vinci for a new cruise.[20]: 184–185

In June 1970, the ship was relocated across the James River to the Norfolk International Terminal, in Norfolk, Virginia. In 1973, USL transferred ownership of the vessel to the United States Maritime Administration. In 1976, Norwegian Caribbean Cruise Line (NCL) was reported to be interested in purchasing the ship and converting her into a Caribbean cruise ship, but the U.S. Maritime Administration refused the sale due to the classified naval design elements of the ship[27] and NCL purchased the former SS France instead. The Navy finally declassified the ship's design features in 1977.[27] That same year, a group headed by Harry Katz sought to purchase the ship and dock her in Atlantic City, New Jersey, where she would be used as a hotel and casino. However, nothing came of the plan.[40] The liner was seen as obsolete for naval use by 1978, and was put up for sale by the U.S. Maritime Administration.

In 1980, the vessel was sold for $5 million to a group headed by Seattle developer Richard H. Hadley, who hoped to revitalize the liner in a timeshare cruise ship format.[citation needed]

In 1984, to pay creditors, the ship's fittings and furniture, which had been left in place since 1969, were sold at auction in Norfolk, Virginia.[41] After a week-long auction between the 8th and 14th of October 1984, about 3,000 bidders paid $1.65 million for objects from the ship. Some of the artwork and furniture went to museums like the Mariners' Museum of Newport News, while the largest collection was installed at the later closed Windmill Point Restaurant in Nags Head, North Carolina.[citation needed]

On March 4, 1989, the vessel was relocated, towed across Hampton Roads to the CSX coal pier in Newport News.[42][page needed]

Richard Hadley's plan of a time-share style cruise ship eventually failed financially, and the ship, which had been seized by US marshals, was put up for auction by the U.S. Maritime Administration on April 27, 1992. At auction, Marmara Marine Inc.—which was headed by Edward Cantor and Fred Mayer with Julide Sadıkoğlu, of the Turkish shipping family, as majority owner—purchased the ship for $2.6 million.[43][44]

The ship was towed to Turkey, departing the US on June 4, 1992, and reaching the Sea of Marmara on July 9. She was then towed to Ukraine, where, in Sevastopol Shipyard, she underwent asbestos removal which lasted from 1993 to 1994.[45] There, the interior of the ship was almost completely stripped down to the bulkheads. The open lifeboats, that would have violated SOLAS regulations should the ship sail again, were removed alongside their davits. Back in the US, no plans were finalized for re-purposing the vessel, and in June 1996, she was towed back across the Atlantic to southern Philadelphia.[46]

Layup in Philadelphia (beginning 1996)[edit]

In November 1997, Edward Cantor purchased the ship for $6 million.[47] Two years later, the SS United States Foundation and the SS United States Conservancy (then known as the SS United States Preservation Society, Inc.) succeeded in having the ship placed on the National Register of Historic Places.[9]

Norwegian Cruise Line (2003–2009)[edit]

In 2003, Norwegian Cruise Line (NCL) purchased the ship at auction from Cantor's estate after his death. NCL's intent was to restore the ship to service in their newly announced American-flagged Hawaiian passenger service called NCL America. United States was one of the few ships eligible to enter such service because of the Passenger Service Act, which requires that any vessel engaged in domestic commerce be built and flagged in the U.S. and operated by a predominantly American crew.[48] NCL began an extensive technical review in late 2003 which determined that the ship was in sound condition. The cruise line cataloged over 100 boxes of the ship's blueprints.[49] In August 2004, NCL commenced feasibility studies regarding retrofitting the vessel, and in May 2006, Tan Sri Lim Kok Thay, chairman of Malaysia-based Star Cruises (the owner of NCL), stated that United States would be coming back as the fourth ship for NCL after a refurbishment.[50] Meanwhile, the Windmill Point restaurant, which had contained some of the original furniture from the ship, closed in 2007. The furniture was donated to the Mariners' Museum and Christopher Newport University, both in Newport News, Virginia.[51]

When NCL America began operation in Hawaii, it operated the ships Pride of America, Pride of Aloha, and Pride of Hawaii, rather than United States. NCL America later withdrew Pride of Aloha and Pride of Hawaii from its Hawaiian service. In February 2009, it was reported that United States would "Soon be listed for sale".[52][53]

Potential scrapping (2009–2010)[edit]

The SS United States Conservancy was created in 2009 to try to save United States by raising funds to purchase her.[54] On July 30, 2009, H. F. Lenfest, a Philadelphia media entrepreneur and philanthropist, pledged a matching grant of $300,000 to help the United States Conservancy purchase the vessel from Star Cruises.[55] Former US president Bill Clinton also endorsed rescue efforts to save the ship, having sailed on her himself in 1968.[11][56]

In March 2010, it was reported that bids for the ship to be sold for scrap were being accepted. Norwegian Cruise Lines, in a press release, noted the large costs associated with keeping United States afloat in her current state—around $800,000 a year—and that because the SS United States Conservancy was unable to tender an offer for the ship, the company was actively seeking a "suitable buyer".[57] By May 7, 2010, over $50,000 was raised by the SS United States Conservancy.[58]

In November 2010, the Conservancy announced a plan to develop a "multi-purpose waterfront complex" with hotels, restaurants, and a casino along the Delaware River in South Philadelphia at the proposed location of the stalled Foxwoods Casino project. A detailed study of the site was revealed in late November 2010, in advance of Pennsylvania's December 10, 2010, deadline for a deal aimed at Harrah's Entertainment taking over the casino project. However, the Conservancy's deal collapsed when on December 16, 2010, the state Gaming Control Board voted to revoke the casino's license.[59]

Conservation (2010–2015)[edit]

The Conservancy eventually bought United States from NCL in February 2011 for a reported $3 million with the help of money donated by philanthropist H.F. Lenfest.[60] The group had funds to last 20 months (from July 1, 2010) that were to go to supporting a development plan to clean the ship of toxins and make the ship financially self-supporting, possibly as a hotel or other development project.[61][62] SS United States Conservancy executive director Dan McSweeney stated that possible locations for the ship included Philadelphia, New York City, and Miami.[61][63]

The conservancy assumed ownership of United States on February 1, 2011.[64][65] Talks about possibly locating the ship in Philadelphia, New York City, or Miami continued into March. In New York City, negotiations with a developer were underway for the ship to become part of Vision 2020, a waterfront redevelopment plan costing $3.3 billion. In Miami, Ocean Group was interested in putting the ship in a slip on the north side of American Airlines Arena.[66] With an additional $5.8 million donation from H. F. Lenfest, the conservancy had about 18 months from March 2011 to make the ship a public attraction.[66] On August 5, 2011, the SS United States Conservancy announced that after conducting two studies focused on placing the ship in Philadelphia, she was, "Not likely to work there for a variety of reasons". However, discussions to locate the ship at her original home port of New York, as a stationary attraction, were reported to be ongoing.[67] The Conservancy's grant specifies that the refit and restoration must be done in the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard for the benefit of the Philadelphia economy, regardless of her eventual mooring site.

On February 7, 2012, preliminary work began on restoration to prepare the ship for a complete reconstruction, although a contract had not yet been signed.[68] In April 2012, a Request for Qualifications was released as the start of an aggressive search for a developer for the ship. A Request for Proposals was issued in May.[69] In July 2012, the Conservancy launched a new online campaign called "Save the United States", a blend of social networking and micro-fundraising that allowed donors to sponsor square inches of a virtual ship for redevelopment while allowing them to upload photos and stories about their experience with the ship. The Conservancy announced that donors to the virtual ship would be featured in an interactive "Wall of Honor" aboard the future SS United States museum.[70][71]

By the end of 2012, a developer was to be chosen, who would put the ship in a selected city by summer 2013.[72] In November 2013, the ship was undergoing a "below-the-deck" makeover, which lasted into 2014, in order to make the ship more appealing to developers as a dockside attraction. The Conservancy was warned that if its plans were not realized quickly, there might be no choice but to sell the ship for scrap.[73] In January 2014, obsolete pieces of the ship were sold to keep up with the $80,000-a-month maintenance costs. Enough money was raised to keep the ship going for another six months, with the hope of finding someone committed to the project, New York City still being the likeliest location.[74]

In August 2014, the ship was still moored in Philadelphia and costs for the ship's rent amounted to $60,000 a month. It was estimated that it would take $1 billion to return United States to service, although a 2016 estimate for restoration as a luxury cruise ship placed the most at only $700 million.[75][76] On September 4, 2014, a final push was made to have the ship bound for New York City. A developer interested in re-purposing the ship as a major waterfront destination made an announcement regarding the move. The Conservancy had only weeks to decide if the ship needed to be sold for scrap.[77] On December 15, 2014, preliminary agreements in support of the redevelopment of United States were announced. The agreements included providing three months of carrying costs, with a timeline and more details to be released sometime in 2015.[78][79] In February 2015, another $250,000 was received by the Conservancy from an anonymous donor towards planning an onboard museum.[80]

In October 2015, the Conservancy began exploring potential bids for scrapping the ship. The group was running out of money to cover rent and maintain the ship. Attempts to re-purpose the ship continued. Ideas included using the ship for hotels, restaurants, or office space. One idea was to install computer servers in the lower decks and link them to software development businesses in office space on the upper decks. However, no firm plans were announced. The conservancy said that if no progress was made by October 31, 2015, they would have no choice but to sell the ship to a "responsible recycler".[81] As the deadline passed it was announced that $100,000 had been raised in October 2015, sparing the ship from immediate danger. By November 23, 2015, it was reported that over $600,000 in donations had been received for care and upkeep, buying time well into the coming year for the SS United States Conservancy to press ahead with a plan to redevelop the vessel.[82]

Crystal Cruises (2016–2018)[edit]

On February 4, 2016, Crystal Cruises announced that it had signed a purchase option for United States. Crystal covered docking costs for nine months while it conducted a feasibility study on returning the ship to service as a cruise ship based in New York City.[83][84] On April 9, 2016, it was announced that 600 artifacts from United States would be returned to the ship from the Mariners' Museum and other donors.[85]

On August 5, 2016, the plan was formally dropped, with Crystal Cruises citing many technical and commercial challenges. The cruise line made a donation of $350,000 to help preservation effort through the end of the year.[86][87][88] The Conservancy continued to receive donations, which included one for $150,000 by cruise industry executive Jim Pollin.[7] In January 2018, the conservancy made an appeal to US president Donald Trump to take action regarding "America's Flagship".[89] If the group runs out of money, alternative plans for the ship include sinking her as an artificial reef rather than scrapping her were made.[7]

On September 20, 2018, the conservancy consulted with Damen Ship Repair & Conversion about redevelopment of United States. Damen had previously converted the former ocean liner and cruise ship SS Rotterdam into a hotel and mixed-use development.[90]

RXR Realty (beginning 2018)[edit]

On December 10, 2018, the conservancy announced an agreement with the commercial real estate firm RXR Realty to explore options for restoring and redeveloping the ocean liner.[91] The conservancy requires that any redevelopment plan must preserve the ship's profile and exterior design, and include approximately 25,000 sq ft (2,323 m2) for an onboard museum.[90] RXR's press release about United States stated that multiple locations would be considered, depending on the viability of restoration plans.[91][92]

In March 2020, RXR Realty announced its plans to repurpose the ocean liner as a permanently-moored 600,000 sq ft (55,740 m2) hospitality and cultural space, requesting expressions of interest from a number of major US waterfront cities including Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Miami, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego.[93]

In 2023, a more detailed plan for her redevelopment was released by RXR Realty and MCR Hotels. According to this plan, the ship would serve as a 1,000 room hotel, museum, event venue, public park, and a dining location. New York City was highlighted as the best location for the ship, ideally along the Hudson River and moored to a specially built pier. New York City was selected as the best location due to existing infrastructure and the nearby Javits Convention Center.[94]

The 2023 plan also included several rendered images of the redesigned United States. These images depict the ship docked along Manhattan's West Side at a public pier located in the Hudson River Park. In addition, aspects of the hotel were depicted. A key element of the hotel would be one of the ship's funnels, with the top removed and exposed to the sky. This would act as a skylight, illuminating the hotel and event spaces. In addition, the plan also consist of hotel rooms held in the lifeboat davits, a pool between the funnels, and an aft mix interior-exterior ballroom to provide spaces for both hotel and venue operations.[94]

Pier 82 rent increase (2021–2024)[edit]

Philadelphia's Pier 82, where the ship is located, is owned by the company Penn Warehouses. In 2021, Penn Warehouses increased the ship's rent from $850 to $1700 per day, requested $160,000 in back rent, and terminated the contract with the conservatory. The company stated the change was due to the United States slowly damaging the pier and the Conservatory refusing to maintain a previous agreement to cover possible damages.[95][96]

The Conservatory responded by stating the rent hike violated an agreement made in 2011, and refused to pay. They accused their landlord of illegally wanting to oust the ship so that the pier could be used for more profitable activities. This lead to both groups suing each other.[96]

Eviction[edit]

A trial ran in federal court from January 17–18, 2024. Presided over by judge Anita Brody, a ruling was handed down on June 14. While Brody encouraged the matter to be settled out of court, she rejected Penn Warehouse's financial demands while ordering the ship to be removed in 90 days (September 12). With such a tight deadline, the conservatory is currently unsure how the liner can be moved or where it would go.[97][98][99] Six days later, the conservatory began a new donation drive and requested $500,000 to help relocate her.[100]

Artifacts[edit]

Artwork[edit]

The Mariners' Museum of Newport News, Virginia, holds many objects from United States, including ''Expressions of Freedom'' by Gwen Lux, an aluminum sculpture from the main dining room that was purchased during the 1984 auction.[41]

Artwork designed by Charles Gilbert that included glass panels etched with sea creatures and plants from the first-class ballroom, were purchased by Celebrity Cruises and had initially been incorporated on board the Infinity in her SS United States-themed specialty restaurant.[101] Other onboard memorabilia, including original porcelain and a model, were moved to the entrance of the ship's casino in 2015.[102][103]

At the National Museum of American History, “The Currents” mural by Raymond John Wendell is on display.[104] Two works by Hildreth Meière—murals Mississippi and Father of Waters—were also brought to the museum and are not on display.[23]

Propellers and fittings[edit]

One of the four-bladed propellers is mounted at Pier 76 in New York City, while the other is mounted outside the American Merchant Marine Museum on the grounds of the United States Merchant Marine Academy in Kings Point, New York. The starboard-side five-bladed propeller is mounted near the waterfront at SUNY Maritime College in Fort Schuyler, New York, while the port side is at the entrance of the Mariner's Museum in Newport News, Virginia, mounted on an original 63 ft (19 m) long drive shaft.[105]

The ship's bell is kept in the clock tower on the campus of Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia. It is used to celebrate special events, including being rung by incoming freshman and by outgoing graduates.[106]

One of the ship's horns stood on display for decades above the Rent-A-Tool building in Revere, Massachusetts, and has since been sold to a private collector in Texas for $8,000 in 2017.[107]

A large collection of dining room furniture and other memorabilia that had been purchased during the 1984 auction, and incorporated at the Windmill Point Restaurant in Nags Head, North Carolina, was donated to the Mariners' Museum and Christopher Newport University in Newport News after the restaurant shut down in 2007.[108] The chairs from the tourist class dining room are used in the Mariners' Museum cafe.[citation needed]

Speed records[edit]

With both the eastbound and westbound speed records, SS United States obtained the Blue Riband which marked the first time a US-flagged ship had held the record since SS Baltic claimed the prize 100 years earlier. United States maintained a 30 kn (56 km/h; 35 mph) crossing speed on the North Atlantic in a service career that lasted 17 years. The ship remained unchallenged for the Blue Riband throughout her career. During this period the fast trans-Atlantic passenger trade moved to air travel, and many regard the story of the Blue Riband as having ended with United States.[109]

Her east-bound record has since been broken several times (first, in 1986, by Virgin Atlantic Challenger II), and her west-bound record was broken in 1990 by Destriero, but these vessels were not passenger-carrying ocean liners. The Hales Trophy itself was lost in 1990 to Hoverspeed Great Britain, setting a new eastbound speed record for a commercial vessel.[110]

In film[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2022) |

Documentaries[edit]

- The Superliners: Twilight of An Era (National Geographic 1985)[111]

- The SS United States: From Dream to Reality (1992, Mariner's Museum)

- Floating Palaces (1996)[112]

- SS United States: Lady in Waiting (2008)

- SS United States: Made in America (2013)

- Inside The Abandoned S.S United States (2021)[113]

Cameos[edit]

- Sabrina (1954)

- Gentlemen Marry Brunettes (1955)[114]

- West Side Story (1961)

- Bon Voyage! (1962)

- Munster, Go Home! (1966)

- Dead Man Down (2013)

See also[edit]

Related American passenger ships[edit]

- SS Leviathan

- SS California (1927)

- SS Virginia (1928)

- SS Pennsylvania (1929)

- SS Manhattan (1931)

- SS Washington (1932)

- SS Santa Rosa (1958)

- MS Pride of America (2002)

Restored ocean liners[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ A double-redaction turbine is a high-speed and a low-speed turbine combined to form one unit. This setup is more efficient at transferring energy than a single-redaction turbine.

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Horne, George (June 24, 1951). "Biggest US Liner 'Launched' in Dock; New Superliner After Being Christened Yesterday". The New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2012.(subscription required)

- ^ Cudahy, Brian J. (1997). Around Manhattan Island and Other Tales of Maritime NY. Fordham University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-8232-1761-8. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Ujifusa, Steven (2012). A Man and his Ship. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4507-1.

- ^ Weinraub, Bernard (November 15, 1969). "Liner United States Laid Up; Competition From Jets a Factor; The United States Cancels Voyages and Is Laid Up". The New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2012.(subscription required)

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ "Retirement and Layup". SS 'United States' Conservancy. 2011. Archived from the original on February 7, 2011. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Adam Leposa (July 19, 2017). "SS United States Gets Last-Minute Reprieve". www.travelagentcentral.com. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ "SS United States Specifications". ss-united-states.com. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ "United States". The Great Ocean Liners. Archived from the original on April 29, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.[self-published source]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Life and Times of the SS United States". The Big U: The Story of the SS United States. ssunitedstates-film.com. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ Dempewolff, Richard F. (June 1952). "America Bids for the Atlantic Blue Ribbon". Popular Mechanics: 81–87, 252, 254. ISSN 0032-4558. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Rindfleisch, James (2023). SS United States: An Operational Guide to America's Flagship. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer. ISBN 978-0764366550.

- ^ Mimi Sheller (2014). Aluminum Dreams: The Making of Light Modernity. MIT Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-262-02682-6.

- ^ "How fast did it go". Nautilus. 25. University of Michigan Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering Department: 8.

- ^ Horne, George (August 16, 1968). "Secrets of the Liner United States". The New York Times. p. 35. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

The decision to unclassify the superior military qualities of the big ship revealed, among other things, that her propulsion plants developed 240,000 horsepower – nearly 100,000 horses more than the world's biggest liners – and that she could make 42 knots, or better than 48 land-miles an hour.

- ^ McKesson, Chris B., ed. (February 13, 1998). "Hull Form and Propulsor Technology for High Speed Sealift" (PDF). John J. McMullen Associates, Inc. pp. 13–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2005. Retrieved December 13, 2009.

- ^ Kane, John R. (April 1, 1978). "The Speed of the SS United States". Marine Technology and SNAME News. 15 (02): 119–143. doi:10.5957/mt1.1978.15.2.119. ISSN 0025-3316.

- ^ Braynard, Frank; Westover, Robert Hudson (2002). S.S. United States. Turner Publishing Company. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-56311-824-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Miller, William H. (1991). SS United States : the story of America's greatest ocean liner. Internet Archive. New York : W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-03030-3.

- ^ "The great lady ship decorators | S.S. American, S.S. United States sailing on the 'All American' team to Europe". united-states-lines.org. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ "S.S. United States". digital.wolfsonian.org. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ocean Liners: S.S. United States: Cabin class lounge wall map – International Hildreth Meière Association Inc". www.hildrethmeiere.org. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ "Early Years". SS United States Conservancy. 2012. Archived from the original on August 26, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ^ Dunlap, David (March 9, 2016). "Beloved Anachronisms, Times Square Mosaics of the City May Be Preserved". New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ "History: Design & Launch – SS United States Conservancy".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Steven Ujifusa (2013). A Man and His Ship: America's Greatest Naval Architect and His Quest to Build the S.S. United States. Simon and Schuster. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-4516-4509-5.

- ^ "Steinway Baby Grand Piano from America's Flagship Now on Public Display". SS United States Conservancy.

- ^ "SS United States Saved, Perhaps to Sail Once More". The Maritime Executive.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "A Three Class Ship – United States Lines & The Heydays of Trans-Atlantic Travel". united-states-lines.org. March 8, 2022. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Maxtone-Graham, John (2014). SS United States : Red, White & Blue Ribband, Forever. Internet Archive. New York : W. W. Norton & Company. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-393-24170-9.

- ^ S.S. United States Miniature Deck Plan. United States Lines.

- ^ Driscoll, Larry (2009). "The Race for the Blue Riband". Archived from the original on May 30, 2009. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- ^ "Atlantic Riband for America". The Times. London. July 8, 1952. p. 6. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved April 27, 2017 – via The Times Digital Archive.

- ^ NY Times (November 13, 1952). Ship speed trophy is presented here.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Driscoll, Larry (Summer 2011). "SS United States: The Last Speed Queen of the Merchant Marine". PowerShips.

- ^ Miller, William H. (2022). SS United States: Ship of Power, Might, and Indecision. Stroud: Fonthill. p. 159 (online). ISBN 1625451156.

- ^ "The Tennessean". www.tennessean.com. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ Colin Larkin, ed. (1992). The Guinness Encyclopedia of Popular Music (First ed.). Guinness Publishing. p. xx. ISBN 0-85112-939-0.

- ^ "Times Daily". Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Reif, Rita (October 15, 1984). "S.S. United States Fans Buy Pieces of History at Ship Auction". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ Braynard, Frank; Westover, Robert Hudson (2002). S.S. United States. ISBN 9781563118241.

- ^ "S.S. United States Sold to Turkish-Backed Group". Daily News. April 29, 1992.

- ^ "$2.6 million bid wins SS United States International group plans renovation". The Baltimore Sun. April 28, 1992.

- ^ Richtun, Tatiana (July 12, 2007). "Асбестовый след корабля 'Юнайтед Стейтс'" [Asbestos footprint of the ship United States]. Sevastopol Gazette (in Russian). Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "Famed Liner's Moving, But There's No Money Yet For A Huge Fixup Will Ship Make City Seasick?". Philadelphia Daily News. August 15, 1996. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014.

- ^ "S.S. United States, The Turkish Years 1992–1996: What Might Have Been". maritimematters.com.

- ^ Deflitch, Gerard (September 28, 2003). "S.S. United States may get chance to relive glory days". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review.

- ^ David Tyler (February 28, 2007). "Return of 'Big U' delayed by problems with Pride of America". professionalmariner.com. Navigator Publishing LLC. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- ^ "Those Three Two Stackers". Maritime Matters. May 24, 2006. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ Morris, Rob (March 1, 2011). "Windmill Point Set to Go Out in a Blaze of Glory". Outer Banks Voice. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- ^ Niemelä, Teijo (February 11, 2009). "SS United States may be offered for sale". Cruise Business Online. Cruise Media Oy Ltd. Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ "United States impending sale?". Maritime Matters. February 10, 2009. Archived from the original on February 19, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ^ "Our History". SS United States Conservancy. Archived from the original on July 6, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ Moran, Robert (July 30, 2009). "Phila. philanthropist to aid purchase of iconic ship". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia Newspapers LLC. Archived from the original on August 3, 2009. Retrieved July 30, 2009.

- ^ "SS United States: America's Ship of State". SS United States Trust. July 4, 2009. Archived from the original on March 24, 2010. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ^ Ujifusa, Steven B. (March 3, 2010). "SS United States now in grave peril". PlanPhilly. Archived from the original on March 7, 2010. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ "Fund Aims To Save S.S. United States". Myfoxphilly.com. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ^ Wittkowski, Donald (December 16, 2010). "Gambling panel revokes license for proposed Foxwoods casino project in Philadelphia". The Press of Atlantic City. The Press of Atlantic City Media Group. Archived from the original on December 19, 2010. Retrieved 2010-12-17.

- ^ Julie Shaw (January 29, 2016). "Is SS United States shipping out for New York?". Philly.com. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pesta, Jesse (July 1, 2010). "Famed Liner Steers Clear of Scrapyard". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 2, 2010. (subscription required)

- ^ Cox, Martin (June 30, 2010). "Preservationists Perched To Buy SS United States". Maritime Matters. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ^ "Powersips". Steamship Historical Society of America. Fall 2010. Archived from the original on November 28, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ Griffin, John (February 1, 2011). "Save Our Ship: Passionate Preservationists Buy a National Treasure". ABC News. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "Video of February 1 Title Transfer Event". SS United States Conservancy. February 9, 2011. Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Knego, Peter (March 16, 2011). "SS United States Latest". Maritime Matters. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "An Update From Conservancy Executive Director Dan McSweeney". SS United States Conservancy. August 5, 2011. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ "Work Begins to Prepare the SS United States for Future Redevelopment". SS United States Conservancy. February 7, 2012. Archived from the original on February 11, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ "SS United States Redevelopment Project Releases Request for Qualifications" (Press release). SS United States Conservancy. April 5, 2012. Archived from the original on September 3, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ "New Online Campaign Launches to Save the United States" (Press release). SS United States Conservancy. July 11, 2012. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ "Save the United States". SS United States Conservancy. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "SS United States To be "Repurposed"". Cruise Industry News. April 5, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "SS United States is being prepared for a new life". Associated Press. November 28, 2013. Archived from the original on December 1, 2013. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ "Will the SS United States find new life in 2014?". philly.com. January 6, 2014. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ "America's flagship: Admirers of SS United States send an S.O.S." america.aljazeera.com. August 12, 2014. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ "The World's Fastest Ocean Liner May Be Restored to Sail Again". National Geographic News. February 8, 2016. Archived from the original on February 9, 2016. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- ^ Backwell, George (September 4, 2014). "SS United States Supporters Push for NY Return". Marine Link. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ "Encouraging New SS United States Developments". maritimematters.com. December 15, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- ^ "Agreement reached to redevelop SS United States". www.bizjournals.com. December 16, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- ^ "SS United States gains $250,000 donation". Philly.com. February 11, 2015. Archived from the original on May 3, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ "Friends of the S.S. United States Send Out a Last S.O.S." The New York Times. October 7, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "Donations Help the S.S. United States Fend Off the Scrapyard". msn.com. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ "Can the SS United States again sail the seas?". philly.com. February 4, 2016. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ "S.S. United States, Historic Ocean Liner of Trans-Atlantic Heyday, May Sail Again". The New York Times. February 4, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ "SS United States getting artifact donations from Mariners' Museum, others". Dailypress. Retrieved April 14, 2016.

- ^ "Crystal Drops SS United States Project". Cruise Industry News. August 5, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ Pesta, Jesse (August 6, 2016). "The S.S. United States Won't Take to the Seas Again After All". The New York Times. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- ^ Adomaitis, Greg (August 8, 2016). "Abandoned ship: Deal to save SS United States 'too challenging'". NJ.com. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- ^ Trina Thompson (January 26, 2018). "Once-majestic cruise ship, the S.S. United States, could be 'America's Flagship' once again". Fox News. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Leading Rotterdam Ship Repair & Conversion Firm Welcomed by Conservancy". wearetheunitedstates.org. SS United States Conservancy. September 20, 2018. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Susan Gibbs (December 10, 2018). "Breaking News: New Agreement with RXR Realty". wearetheunitedstates.org. SS United States Conservancy. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ^ Jacob Adelman (December 12, 2018). "NYC developer with Manhattan pier project in deal to explore reviving SS United States". philly.com. Philly.com/Philadelphia Media Network (Digital), LLC. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ^ The Maritime Executive (March 11, 2020). "U.S. Cities Offered SS United States as Cultural Space". Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Transformative Plan Unveiled to Save America's Flagship". SS United States Conservancy. November 2, 2023. Archived from the original on November 2, 2023. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ Conde, Ximena (January 31, 2023). "The SS United States is in a rent dispute that could leave it without a berth". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Conde, Ximena (June 14, 2024). "SS United States must leave its South Philadelphia berth by mid-September, judge rules". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ "Iconic Ocean Liner SS United States Ordered to Leave Berth by September". The Maritime Executive. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ Conde, Ximena (January 17, 2024). "SS United States is 'every landlord's nightmare,' pier's lawyer says as rent dispute goes to trial". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ Guilhem, Matt (March 11, 2024). "The Fastest Ocean Liner to Cross the Atlantic Faces Eviction from Pier". NPR.org.

- ^ "Symbol of the Nation Evicted: Nonprofit Sending Out An Urgent Call to Help Save America's Flagship". SS United States Conservancy. June 20, 2024. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ^ "S.S. United States – Celebrity Infinity". Cruise to Travel. May 10, 2014. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ Sloan, Gene. "Celebrity Cruises to jettison history-filled restaurants". USA Today. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ "S.S. United States – Celebrity Infinity". CruiseToTravel. May 10, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ "Mural Painting, The Currents". National Museum of American History. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ "The SS United States' Preserved Propellers" (PDF). SS United States Conservancy. June 2014.

- ^ "Traditions – Who We Are". Christopher Newport University. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ Staff, Journal (April 22, 2017). "Rent-A-Tool to Close April 25 After 63 Years in Business". reverejournal.com. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ "Windmill Point set to go out in a blaze of glory". The Outer Banks Voice. March 2, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ Kludas, Arnold (April 2002). Record Breakers of the North Atlantic: The Blue Riband Liners, 1838–1952. Brassey, Inc. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-57488-458-6. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ^ "HSC HOVERSPEED GREAT BRITAIN (1990)". www.faktaomfartyg.se. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ The Superliners: Twilight of an Era (Documentary, History), May 26, 1985, retrieved May 15, 2021

- ^ Weaver, Fritz (April 26, 1996), Floating Palaces, retrieved May 15, 2021

- ^ Inside The ABANDONED S.S United States, July 23, 2021, archived from the original on December 12, 2021, retrieved July 25, 2021

- ^ Conservancy, SSUS (October 25, 2017). "SS United States on Screen: Gentlemen Marry Brunettes (1955)". we-are-the-us. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

Bibliography[edit]

- A Man and His Ship: America's Greatest Naval Architect and His Quest to Build the S.S. United States, Steven Ujifusa, Simon & Schuster; Reprint ed., (2013), ISBN 1451645090

- Crossing on Time: Steam Engines, Fast Ships, and a Journey to the New World, David Macaulay, Roaring Brook Press (2019), ISBN 978-1596434776

- Picture History of the SS United States, William H. Miller, Dover Publications (2012), ASIN B00A73FIMK

- SS United States: An Operational Guide to America's Flagship, James Rindfleisch, Schiffer; (2023), ISBN 978-0764366550

- SS United States: America's Superliner, Les Streater, Maritime Publishing Co. (2011), ISBN 0953103560

- S.S. United States: The Story of America's Greatest Ocean Liner, William H. Miller, W.W. Norton & Company (1991), ISBN 0393030628

- S.S. United States: Fastest Ship in the World, Frank Braynard & Robert Hudson Westover, Turner Publishing Company (2002), ISBN 1563118246

- SS United States, Andrew Britton, The History Press (2012), ISBN 0752479539

- SS United States: Red, White, and Blue Riband, Forever, John Maxtone-Graham, W.W. Norton & Company; 1st ed. (2014), ISBN 039324170X

- SS United States: Speed Queen of the Seas, William H. Miller, Amberley Publishing (2015), ASIN B00V76G2O4

- SS United States: Ship of Power, Might, and Indecision, William H. Miller, Fonthill Media, (2022), ISBN 1625451156

- Superliner S.S. United States, Henry Billings, The Viking Press (1953)

- Braynard, Frank O. (2011) [1981]. The big ship : the story of the S.S. United States (New ed.). New York: Turner. ISBN 978-1596527645. OCLC 745439004.

- The Last Great Race, The S.S. United States and the Blue Riband, Lawrence M. Driscoll, The Glencannon Press; 1st ed., (2013) [ISBN missing]

External links[edit]

Documents[edit]

- SS United States Conservancy, current owner of SS United States

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. PA-647, "SS United States"

- First Class Deck Plan Archived October 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Cabin Class Deck Plan Archived October 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Tourist Class Deck Plan Archived October 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- SS United States, archive of various stories from the united-states-lines.org website

Artwork[edit]

- Williams, C. K. (April 16, 2007). "Poetry – The United States". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014.

- SS United States Onboard Artwork: Hildreth Meière, images of several onboard pieces

Video[edit]

- Inside the Abandoned S.S. United States, 2021 YouTube tour video

Other[edit]

- SS United States Archived July 2, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, the defunct website of the conservatory

- Information on SS United States from vesselfinder.com This page gives a list of registered owners of the ship

- Ocean liners

- Steamships of the United States

- National Register of Historic Places in Philadelphia

- Blue Riband holders

- Historic American Engineering Record in Philadelphia

- Passenger ships of the United States

- Ships built in Newport News, Virginia

- Ships of the United States Lines

- Ships on the National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania

- 1951 ships

- Troop ships

![First-class cabin U 141, showing mid-century modern furnishings and the lack of detail common throughout the ship. Not shown is the cabin's private bath.[32]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c4/S.S._United_States._LOC_gsc.5a21876.tif/lossy-page1-120px-S.S._United_States._LOC_gsc.5a21876.tif.jpg)