Zazen

| Zazen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 坐禪 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 坐禅 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | seated meditation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | toạ thiền | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 坐禪 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 좌선 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 坐禪 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 坐禅 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | ざぜん | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Zen Buddhism |

|---|

|

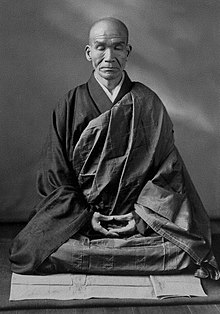

Zazen is a meditative discipline that is typically the primary practice of the Zen Buddhist tradition.[1][2]

The generalized Japanese term for meditation is 瞑想 (meisō);[3] however, zazen has been used informally to include all forms of seated Buddhist meditation. The term zuòchán can be found in early Chinese Buddhist sources, such as the Dhyāna sutras. For example, the famous translator Kumārajīva (344–413) translated a work termed Zuòchán sān mēi jīng (A Manual on the Samādhi of Sitting Meditation) and the Chinese Tiantai master Zhiyi (538–597 CE) wrote some very influential works on sitting meditation.[4][5]

The meaning and method of zazen varies from school to school, but in general it is a quiet type of Buddhist meditation done in a sitting posture like the lotus position. The practice can be done with various methods, such as following the breath (anapanasati), mentally repeating a phrase (which could be a koan, a mantra, a huatou or nianfo) and a kind of open monitoring in which one is aware of whatever comes to our attention (sometimes called shikantaza or silent illumination). Repeating a huatou, a short meditation phrase, is a common method in Chinese Chan and Korean Seon. Meanwhile, nianfo, the practice of silently reciting the Buddha Amitabha's name, is common in the traditions influenced by Pure Land practice, and was also taught by Chan masters like Zongmi.[6]

In the Japanese Buddhist Rinzai school, zazen is usually combined with the study of koans. The Japanese Sōtō school makes less or no use of koans, preferring an approach known as shikantaza where the mind has no object at all.[7]

Practice

[edit]Five types of Zazen

[edit]Kapleau quotes Hakuun Yasutani's lectures for beginners. In lecture four, Yasutani lists five kinds of zazen:

- bompu, developing meditative concentration to aid well-being;

- gedo, zazen-like practices from other religious traditions;

- shojo, 'small vehicle' practices;

- daijo, zazen aimed at gaining insight into true nature;

- saijojo, shikantaza.[8]

Sitting

[edit]

In Zen temples and monasteries, practitioners traditionally sit zazen together in a meditation hall usually referred to as a zendo, each sitting on a cushion called a zafu[2] which itself may be placed on a low, flat mat called a zabuton.[2] Practitioners of the Rinzai school sit facing each other with their backs to the wall, while those of the Sōtō school sit facing the wall or a curtain.[9] Before taking one's seat, and after rising at the end of a period of zazen, a Zen practitioner performs a gassho bow to their seat, and a second bow to fellow practitioners.[10] The beginning of a period of zazen is traditionally announced by ringing a bell three times (shijosho), and the end of the period by ringing the bell either once or twice (hozensho). Long periods of zazen may alternate with periods of kinhin (walking meditation).[11][12]

Posture

[edit]The posture of zazen is seated, with crossed legs and folded hands, and an erect but settled spine.[13] The hands are folded together into a simple mudra over the belly.[13] In many practices, the practitioner breathes from the hara (the center of gravity in the belly) and the eyelids are half-lowered, the eyes being neither fully open nor shut so that the practitioner is neither distracted by, nor turning away from, external stimuli.

The legs are folded in one of the standard sitting styles:[2]

- Kekkafuza (full-lotus)

- Hankafuza (half-lotus)

- Burmese (a cross-legged posture in which the ankles are placed together in front of the sitter)

- Seiza (a kneeling posture using a bench or zafu)

It is not uncommon for modern practitioners to practice zazen in a chair,[2] sometimes with a wedge or cushion on top of it so that one is sitting on an incline, or by placing a wedge behind the lower back to help maintain the natural curve of the spine.

Samadhi

[edit]The initial stages of training in zazen resemble traditional Buddhist samatha meditation. The student begins by focusing on the breath at the hara/tanden[14] with mindfulness of breath (ānāpānasmṛti) exercises such as counting breath (sūsokukan 数息観) or just watching it (zuisokukan 随息観). Mantras are also sometimes used in place of counting. Practice is typically to be continued in one of these ways until there is adequate "one-pointedness" of mind to constitute an initial experience of samadhi. At this point, the practitioner moves on to koan-practice or shikantaza.

While Yasutani Roshi states that the development of jōriki (定力) (Sanskrit samādhibala), the power of concentration, is one of the three aims of zazen,[15] Dogen warns that the aim of zazen is not the development of mindless concentration.[16]

Koan introspection

[edit]In the Rinzai school, after having developed awareness, the practitioner can now focus their consciousness on a koan as an object of meditation. While koan practice is generally associated with the Rinzai school and Shikantaza with the Sōtō school, many Zen communities use both methods depending on the teacher and students.

Shikantaza

[edit]Zazen is considered the heart of Japanese Sōtō Zen Buddhist practice.[1][17] The aim of zazen is just sitting, that is, suspending all judgemental thinking and letting words, ideas, images and thoughts pass by without getting involved in them.[7][18] Practitioners do not use any specific object of meditation,[7] instead remaining as much as possible in the present moment, aware of and observing what is occurring around them and what is passing through their minds. In his Shobogenzo, Dogen says, "Sitting fixedly, think of not thinking. How do you think of not thinking? Nonthinking. This is the art of zazen."[19]

See also

[edit]- Ango – Concept of Japanese Buddhism

- Jing zuo – Meditation practice

- Keisaku – Buddhist ritual implement

- Kinhin – Buddhist meditative practice

- Sesshin – Period of intensive meditation

- Suizen – Wandering medicants recognized by their flute-playing

- Zuowang – Daoist meditation technique

References

[edit]- ^ a b Warner, Brad (2003). Hardcore Zen: Punk Rock, Monster Movies, & the Truth about Reality. Wisdom Publications. p. 86. ISBN 086171380X.

- ^ a b c d e "Zazen Instructions". Zen Mountain Monastery. December 30, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ^ 保坂俊司 『仏教とヨーガ』東京書籍 、2004年。https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/瞑想

- ^ Yamabe, Nobuyoshi; Sueki, Fumihiko (2009). The sutra on the concentration of sitting meditation (Taishō Volume 15, Number 614), pp. xiv-xvii. Berkeley: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research.

- ^ Swanson, Paul L. "Ch'an and Chih-kuan T'ien-t'ai Chih-i's View of "Zen" and the Practice of the Lotus Sutra" (PDF). Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Jones, Charles Brewer (2021). Pure land: history, tradition, and practice. Boulder, Colorado: Shambhala. ISBN 978-1-61180-890-2.

- ^ a b c Warner, Brad (2003). Hardcore Zen: Punk Rock, Monster Movies, & the Truth about Reality. Wisdom Publications. pp. 189–190. ISBN 086171380X.

- ^ Kapleau, Philip (1989). The Three pillars of Zen: teaching, practice, and enlightenment. New York: Anchor Books. pp. 48–53. ISBN 0-385-26093-8.

- ^ Kapleau, Philip (1989). The Three pillars of Zen: teaching, practice, and enlightenment. New York: Anchor Books. p. 10(8). ISBN 0-385-26093-8.

- ^ Warner, Brad. "How To Sit Zazen". Dogen Sangha Los Angeles. Archived from the original on March 16, 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ^ Heine, Steven; Wright, Dale S., eds. (2007). Zen Ritual : Studies of Zen Buddhist Theory in Practice: Studies of Zen Buddhist Theory in Practice. Oxford University Press. p. 223. ISBN 9780198041467.

- ^ Maezumi, Hakuyu Taizan; Glassman, Bernie (2002). On Zen Practice: Body, Breath, Mind. Wisdom Publications. pp. 48–49. ISBN 086171315X.

- ^ a b Suzuki, Shunryū (2011). Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind. Shambhala Publications. p. 8. ISBN 978-159030849-3.

- ^ Eihei Dogen; Taigen Dan Leighton; Shōhaku Okumura; John Daido Loori (16 March 2010). Dogen's Extensive Record: A Translation of the Eihei Koroku. Simon and Schuster. pp. 348–349. ISBN 978-0-86171-670-8.

- ^ Philip Kapleau, The three pillars of Zen.

- ^ Carl Bielefeldt (16 August 1990). Dogen's Manuals of Zen Meditation. University of California Press. pp. 137–. ISBN 978-0-520-90978-6.

- ^ Deshimaru, Taisen (1981) The Way of True Zen, American Zen Association, ISBN 978-0972804943

- ^ Suzuki, Shunryū (2011). Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind. Shambhala Publications. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-159030849-3.

- ^ "Sotan Tatsugami Roshi Dogen". web.stanford.edu. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Austin, James H (1999). Zen and the Brain: Toward an Understanding of Meditation and Consciousness. The MIT Press. ISBN 0262011646.

- Buksbazen, John Daishin (2002). Zen Meditation in Plain English. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0861713168.

- Tanahashi, Kazuaki (2004). Beyond Thinking: A Guide to Zen Meditation. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 1590300246.

- Harada, Sekkei (1998). The Essence of Zen: Dharma Talks Given in Europe and America. Kodansha. ISBN 4770021992.

- Humphreys, Christmas (1991). Concentration and Meditation: A Manual of Mind Development. Element Books. ISBN 1852300086.

- Loori, John Daido (2007). Finding the Still Point: A Beginner's Guide to Zen Meditation. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 978-1590304792.

- Loori, John Daido; Leighton, Taigen Daniel (2004). The art of just sitting: Essential writings of the Zen practice of shikantaza. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 086171394X.