A Streetcar Named Desire (1951 film)

| A Streetcar Named Desire | |

|---|---|

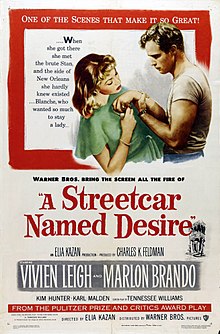

Theatrical release poster by Bill Gold | |

| Directed by | Elia Kazan |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | A Streetcar Named Desire 1947 play by Tennessee Williams |

| Produced by | Charles K. Feldman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Harry Stradling |

| Edited by | David Weisbart |

| Music by | Alex North |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 125 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.8 million[3] |

| Box office | $8 million (North America)[3] |

A Streetcar Named Desire is a 1951 American Southern Gothic drama film adapted from Tennessee Williams's Pulitzer Prize-winning play of the same name. It is directed by Elia Kazan, and stars Vivien Leigh, Marlon Brando, Kim Hunter, and Karl Malden. The film tells the story of a Mississippi Southern belle, Blanche DuBois, who, after encountering a series of personal losses, seeks refuge with her sister and brother-in-law in a dilapidated New Orleans apartment building. The original Broadway production and cast was converted to film, albeit with several changes and sanitizations related to censorship.

Tennessee Williams collaborated with Oscar Saul and Elia Kazan on the screenplay. Kazan, who directed the Broadway stage production, also directed the black-and-white film. Brando, Hunter, and Malden all reprised their original Broadway roles. Although Jessica Tandy originated the role of Blanche DuBois on Broadway, Vivien Leigh, who had appeared in the London theatre production, was cast in the film adaptation for her star power.[4] Upon release of the film, Marlon Brando, virtually unknown at the time of the play's casting, rose to prominence as a major Hollywood film star, and received the first of four consecutive Academy Award nominations for Best Actor, while Leigh won her second Academy Award for Best Actress for playing DuBois.

The film earned an estimated $4,250,000 at the US and Canadian box office in 1951, making it the fifth biggest hit of the year.[5] It received Oscar nominations in 10 other categories (including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay), and won Best Supporting Actor (Malden), Best Supporting Actress (Hunter), and Best Art Direction (Richard Day, George James Hopkins), making it the first film to win in three of the acting categories. In 1999, A Streetcar Named Desire was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Plot

[edit]Blanche DuBois, a middle-aged high school English teacher, arrives in New Orleans. She takes a streetcar named "Desire"[6] to the French Quarter, where her sister, Stella, and Stella's husband, Stanley Kowalski, live in a tenement apartment. Blanche claims to be on leave from her teaching job due to her nerves and wants to stay with Stella and Stanley. Blanche's demure, refined manner is a stark contrast to Stanley's crude, brutish behavior, making them mutually wary and antagonistic. Stella welcomes having her sister as a guest, but Stanley often patronizes and criticizes her.

Blanche reveals that the family estate, Belle Reve, was lost to creditors, and Blanche is broke with nowhere to go. She was widowed at a young age after her husband's suicide. When Stanley suspects Blanche may be hiding an inheritance, she shows him proof of the foreclosure. Stanley, looking for further proof, knocks some of Blanche's private papers to the floor. Weeping, she gathers them, saying they are poems from her dead husband. Stanley explains he was only looking out for his family, then announces Stella is pregnant.

Blanche meets Stanley's friend, Mitch, whose courteous manner is in sharp contrast to Stanley's other pals. Mitch is attracted to Blanche's flirtatious charm, and a romance blossoms. During a poker night with his friends, Stanley explodes in a drunken rage, striking Stella and ending the game; Blanche and Stella flee to neighbor Eunice Hubbell's upstairs apartment. After his anger subsides, Stanley remorsefully bellows for Stella from the courtyard below. Irresistibly drawn by her physical passion for him, she goes to Stanley, who carries her off to bed. The next morning, Blanche urges Stella to leave Stanley, calling him a sub-human animal. Stella disagrees and stays.

As weeks pass into months, tension mounts between Blanche and Stanley. Blanche is hopeful about Mitch, but anxiety and alcoholism have her teetering on mental collapse while anticipating a marriage proposal. Finally, Mitch says they should be together. Meanwhile, Stanley uncovers Blanche's hidden history of mental instability, promiscuity, and being fired for sleeping with an underage student. He passes this news on to Mitch, in full knowledge this will end Blanche's marriage prospects and leave her with no future. Stella angrily blames Stanley for the catastrophic revelation, but their fight is interrupted when Stella goes into labor.

Later, Mitch arrives and confronts Blanche about Stanley's claims. She initially denies everything, then breaks down confessing. She pleads for forgiveness, but Mitch, hurt and humiliated, roughly ends the relationship. Later that night, while Stella's labor continues, Stanley returns from the hospital to get some sleep. Blanche, dressed in a tattered old gown, pretends she is departing on a trip with an old admirer. She spins tale after tale about her fictitious future plans, and he pitilessly destroys her illusions. They engage in a struggle. She collapses and the scene ends with her impending rape.

Weeks later, during another poker game at the Kowalski apartment, doctors arrive to take the nearly catatonic Blanche to a mental hospital. Blanche has told Stella what happened, but Stella cannot bring herself to believe it. On seeing the doctor and nurse, Blanche resists at first. The nurse matron seizes her but the doctor talks to her gently and she goes with them, saying her last lines in the play about having "always depended on the kindness of strangers". Mitch, present at the poker game, is visibly upset, and although Stanley denies touching Blanche, Mitch attacks him but is no match for the shorter but tougher Stanley. Stella, now realizing that Blanche had told her the truth, takes the baby upstairs to the Hubbells' apartment, determined to leave her husband.

Cast

[edit]

- Vivien Leigh as Blanche

- Marlon Brando as Stanley

- Kim Hunter as Stella

- Karl Malden as Mitch

- Rudy Bond as Steve Hubbell

- Peg Hillias as Eunice Hubbell

- Nick Dennis as Pablo

- Wright King as a collector

- Edna Thomas as Mexican Woman

- Ann Dere as Matron Nurse

- Richard Garrick as Doctor

- Mickey Kuhn as Sailor

- Lyle Latell as Policeman (uncredited)

Production

[edit]A Streetcar Named Desire was adapted directly from the successful 1947 Broadway production of the play, which won the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award for Best Play and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Many of the cast and crew were ported over from the stage production, including director Elia Kazan and actors Marlon Brando, Kim Hunter, Karl Malden, Rudy Bond, Nick Dennis, Peg Hillias, Ann Dere, Edna Thomas, and Richard Garrick. Kazan intended for Jessica Tandy, who won a Tony for her portrayal of Blanche, to also reprise her role on film, but producer Charles K. Feldman insisted on casting an actress with more box office appeal. The role was offered to both Bette Davis[7] and Olivia de Havilland, who both declined. Vivien Leigh, who had already played Blanche in Streetcar's London production (directed by then-husband Laurence Olivier), was eventually cast. In Brando's autobiography, he praised Tandy but felt that Vivien Leigh ended up being the definitive Blanche. "She was Blanche."

Aside from the opening and closing scenes, which were shot on location in New Orleans, A Streetcar Named Desire was filmed entirely on soundstages at the Warner Bros. Studios in Burbank, California. The Kowalski apartment set was designed to gradually appear smaller over the course of the film, to reflect the characters' sense of claustrophobia.

For the opening scene, #922 was chosen to be the streetcar that dropped off Blanche. This streetcar is still in revenue earning service on the St. Charles Streetcar Line[8]

Marlon Brando is often displayed shirtless, in one of the first occurrences for a Hollywood movie.[9]

Censorship

[edit]Several scenes were shot, but cut, after filming was complete, to conform to the Production Code and later, to avoid condemnation by the National Legion of Decency. In 1993, after Warner Bros. discovered the censored footage during a routine inventory of archives,[10] several minutes of the censored scenes were restored in an 'original director's version' video re-release.[11]

Music

[edit]The jazz-infused score by Alex North was written in short sets of music that reflected the psychological dynamics of the characters. It was one of the first jazz scores composed for a mainstream feature film,[12] and earned North an Oscar nomination for Best Original Score, one of two nominations in that category that year.

Comparison to source material

[edit]- The play was set entirely at the Kowalski apartment, but the story's visual scope is expanded in the film, which depicts locations only briefly mentioned or non-existent in the stage production, such as the train station, streets in the French Quarter, the bowling alley, the pier of a dance casino, and the machine factory.

- Dialogue presented in the play is abbreviated or cut entirely in various scenes in the film, including, for example, when Blanche tries to convince Stella to leave Stanley and when Mitch confronts Blanche about her past.

- The name of the town where Blanche was from was changed from the real-life town of Laurel, Mississippi, to the fictional "Auriol, Mississippi".

- The play's themes were controversial, causing the screenplay to be modified to comply with the Hollywood Production Code. In the original play, Blanche's husband died by suicide after he was discovered having a homosexual affair. This reference was removed from the film; Blanche says instead that she showed scorn at her husband's sensitive nature, driving him to suicide. She does however make a vague reference to "his coming out", implying homosexuality without explicitly stating it.

- The scene involving Stanley raping Blanche is cut short in the film, instead ending dramatically with Blanche smashing the mirror with the broken bottle in a failed attempt at self-defence.

- At the end of the play, Stella, distraught at Blanche's fate, mutely allows Stanley to console her. In the film, this is changed to Stella blaming Stanley for Blanche's fate, and resolving to leave him.[13]

- Close, tight photography altered the dramatic qualities of the play, for example in the lengthy scenes of escalating conflict between Stanley and Blanche, or when Mitch shines the light on Blanche to see how old she is, or when the camera hovers over Blanche, collapsed on the floor, with her head at the bottom of the screen, as though she were turned upside down.

- In the film, Blanche is shown riding in the streetcar which was only mentioned in the play. By the time the film was in production, however, the Desire streetcar line had been converted into a bus service, and the production team had to gain permission from the authorities to hire out a streetcar with the "Desire" name on it.[14]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]In the months after its release in September 1951, A Streetcar Named Desire grossed $4.2 million in the United States and Canada, with 15 million tickets sold against a production budget of $1.8 million.[15] A reissue of the film by 20th Century Fox in 1958 grossed an additional $700,000.[16]

Critical response

[edit]Upon release, the film drew very high praise. The New York Times critic Bosley Crowther stated that "inner torments are seldom projected with such sensitivity and clarity on the screen" and commending both Vivien Leigh's and Marlon Brando's performances. Film critic Roger Ebert has also expressed praise for the film, calling it a "great ensemble of the movies." The film has a 97% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 62 reviews, with an average rating of 8.60/10. The consensus reads, "A feverish rendition of a heart-rending story, A Streetcar Named Desire gives Tennessee Williams's stage play explosive power on the screen thanks to Elia Kazan's searing direction and a sterling ensemble at the peak of their craft."[17]

In his 2020 autobiography Apropos of Nothing, director Woody Allen praises every aspect of the production:

The movie Streetcar is for me total artistic perfection... It's the most perfect confluence of script, performance, and direction I’ve ever seen. I agree with Richard Schickel, who calls the play perfect. The characters are so perfectly written, every nuance, every instinct, every line of dialogue is the best choice of all those available in the known universe. All the performances are sensational. Vivien Leigh is incomparable, more real and vivid than real people I know. And Marlon Brando was a living poem. He was an actor who came on the scene and changed the history of acting. The magic, the setting, New Orleans, the French Quarter, the rainy humid afternoons, the poker night. Artistic genius, no holds barred.

The Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa cited this movie as one of his 100 favorite films.[18]

Awards and nominations

[edit]A Streetcar Named Desire won four Academy Awards, setting an Oscar record when it became the first film to win in three of the acting categories, a feat subsequently matched by Network in 1976 and Everything Everywhere All at Once in 2022.[19][20] It was also the first time since 1936 (Anthony Adverse) that a Warner Bros. movie won four or more Oscars.

American Film Institute recognition

- 1998 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies No. 45

- 2002 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Passions No. 67

- 2005 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes:

- "Stella! Hey, Stella!" No. 45

- "I've always depended on the kindness of strangers," No. 75

- 2005 AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores No. 19

- 2007 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) No. 47

References

[edit]- ^ A Streetcar Named Desire at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved Sept. 19, 2021

- ^ "A Streetcar Named Desire". American Film Institute. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- ^ a b "A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)—Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ Manvell, Roger. Theatre and Film: A Comparative Study of the Two Forms of Dramatic Art, and of the Problems of Adaptation of Stage Plays into Films. Cranbury, New Jersey: Associated University Presses Inc, 1979. 133

- ^ 'The Top Box Office Hits of 1951', Variety, January 2, 1952

- ^ "Named 'Desire'" in the sense that the streetcar has a roll sign up front declaring its route's destination, namely Rue Desiré in the Bywater neighborhood. The street was named at about the time of the Louisiana Purchase by the plantation owner, Robert Gautier de Montreuil, as a tribute to his third daughter, Desirée. Coincidentally, the streetcar company ceased that route in 1948, a year after the play was written.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "The real Desire Streetcar - A New Orleans Story". June 2022.

- ^ Frances Romero (August 18, 2011). "Top 10 Shirtless Movies: A Streetcar Named Desire".

- ^ Warner Archive Podcast (June 3, 2014).

- ^ Censored Films and Television at University of Virginia online

- ^ "Jazz on Film: the brilliance of 'A Streetcar Named Desire'". Jazzwise. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ Williams, Tennessee, Memoirs, 1977

- ^ "New Orleans Public Service, Inc. 832". Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Annual Movie Chart | 1951–1952 | the numbers

- ^ "'Streetcar' New Run Heads For $700,000". Variety. November 11, 1958. p. 5. Retrieved July 7, 2019 – via Archive.org.

- ^ A Streetcar Named Desire at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ Thomas-Mason, Lee (January 12, 2021). "From Stanley Kubrick to Martin Scorsese: Akira Kurosawa once named his top 100 favourite films of all time". Far Out Magazine. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- ^ "The 24th Academy Awards (1952) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

- ^ "NY Times: A Streetcar Named Desire". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2009. Archived from the original on January 25, 2009. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

External links

[edit]- A Streetcar Named Desire at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- A Streetcar Named Desire at IMDb

- A Streetcar Named Desire at the TCM Movie Database

- A Streetcar Named Desire at AllMovie

- A Streetcar Named Desire at Rotten Tomatoes

- Werner, Stephen A., “In Search of Stanley Kowalski” St. Louis Cultural History Project (Summer 2022).

- 1951 films

- 1951 drama films

- American drama films

- 1950s English-language films

- Films directed by Elia Kazan

- Films with screenplays by Tennessee Williams

- American black-and-white films

- Films about educators

- Films about inheritances

- Films about rape in the United States

- Films scored by Alex North

- American films based on plays

- Films featuring a Best Actress Academy Award-winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award-winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actress Academy Award-winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actress Golden Globe-winning performance

- Films set in New Orleans

- Films shot in New Orleans

- Films set in Louisiana

- Films whose art director won the Best Art Direction Academy Award

- Rail transport films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Venice Grand Jury Prize winners

- Southern Gothic films

- Films based on works by Tennessee Williams

- Warner Bros. films

- 1950s American films