Blockade Strategy Board

The Blockade Strategy Board, also known as the Commission of Conference, or the Du Pont Board, was a strategy group created by the United States Navy Department at outset of the American Civil War to lay out a preliminary strategy for enforcing President Abraham Lincoln's April 19, 1861 Proclamation of Blockade Against Southern Ports. Enforcing this blockade would require the monitoring of 3,500 miles (5,633 km) of Atlantic and Gulf coastline held by the Confederate States of America, including 12 major ports, notably New Orleans and Mobile. The group, consisting of: Samuel Francis Du Pont, who acted as chairman; Charles Henry Davis; John Gross Barnard; and Alexander Dallas Bache, met in June to determine how best to cut off maritime transport to and from these seaports. Their reports for the Atlantic seaboard were used, with modifications, to direct the early course of the naval war. Their analysis of the Gulf Coast was not so successful, largely because the detailed oceanographic knowledge that marked the Atlantic reports was not available for the Gulf.

Background

[edit]Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor was bombarded and seized by the Confederate States Army on April 12–14, 1861, thereby initiating the Civil War. Following the outbreak of hostilities, on April 19, President Lincoln proclaimed a blockade of all ports in the states that had seceded from the Union at that time: South Carolina; Georgia; Florida; Alabama; Mississippi; Louisiana; and Texas. Later, when the coastal states of Virginia and North Carolina also seceded, the proclamation was modified to include their ports as well.[1]

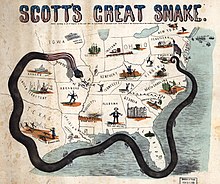

The blockade, which existed only on paper at this time, became an integral part of the plan to persuade the seceded states to return to the Union that was proposed by General in Chief Winfield Scott. Although Scott's so-called Anaconda Plan was never formally adopted as a strategy to guide the conduct of the war, the U.S. Navy enforced the blockade to the best of its ability for the duration of the conflict.

At the beginning of the war, the Union Navy's ability to carry out its Blockade of Confederate maritime ports was woefully inadequate. It had only 90 ships of all types, and only 42 that were powered by steam. A frenzied program of shipbuilding and conversions of existing merchant vessels increased the number to 671 by the end of the war,[2] but as they came into service, their assignments had to be prioritized.

The person in Lincoln's cabinet most concerned with rationalizing the blockade was Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase. Treasury's Revenue Cutter Service was the agency most familiar with the nation's ports, and the knowledge of harbor bottoms held by its Coast Survey would be needed by the naval commanders who patrolled their waters. He persuaded Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles to set up a commission to study the entire Southern coast, and on June 25, 1861 Welles issued the necessary orders to Captain (later Rear Admiral) Samuel Francis Du Pont. At the same time, he ordered Commander (later Rear Admiral) Charles Henry Davis to the board to serve as secretary, and requested that Army Major (later Major General) John G. Barnard, chief of the Army Corps of Engineers, and Alexander D. Bache, Superintendent of the Coast Survey, lend their services.[3] Other persons gave advice, but all reports issued by the commission were signed only by these four.

Reports

[edit] S. F. Du Pont, Chairman |

Charles Henry Davis, Secretary | |

Alexander D. Bache |

John G. Barnard |

The board delivered seven reports to the Navy Department between July 5 and September 19, 1861. Each of them has been published as part of the Official Records of the American Civil War. In chronological order they are:

- July 5, 1861 – ORN I, volume 12, pages 195–198.

Deals with Fernandina, Florida and its harbor. Recommends seizing it as the southern anchor to the Atlantic blockading line. - July 13, 1861 – ORA I, volume 53, pages 67–73.

Considers the South Carolina coast, particularly Bull's Bay, St. Helena Sound, and Port Royal Sound. Recommends seizure and occupation of at least one. - July 16, 1861 – ORN I, volume 12, pages 198–201.

Recommends dividing the Atlantic Blockading Squadron in two, to be separated at Cape Romain in South Carolina. Suggests ways to complete blockade between Cape Henry and Cape Romain. - July 26, 1861 – ORN I, volume 12, pages 201–206.

Deals with the parts of the Atlantic blockade not covered in the reports of July 13 and 16. - August 9, 1861 – ORN I, volume 16, pages 618–630.

Distinguishes six regions of the Gulf coast, and restricts recommendations to the sections covering New Orleans and Mobile. Suggests that Ship Island be captured as a staging ground for operations against either or both. - September 3, 1861 – ORN I, volume 16, pages 651–655.

Deals with Gulf coast other than the parts not considered in report of 9 August. - September 19, 1861 – ORN I, volume 16, pages 680–681.

Considers Ship Island and the lower Mississippi River in greater detail than report of August 9.

Impact

[edit]The recommendations of the board for the Atlantic blockade were mostly accepted, with modifications, by the Lincoln administration. The capture of Fernandina, proposed as the initial offensive action of the Union Navy, was postponed until after the capture of Hatteras Island and Port Royal. The suggestion that Hatteras Inlet be blocked up was overruled by Flag Officer Silas Stringham and Brig. General Benjamin F. Butler, the men who led the expedition.[4] (The board had anticipated that its recommendations would not be followed to the letter. In their report, they included the statement that "These plans may undergo some modification in the hands of the person to whom their execution shall be intrusted.")[5]

The capture of Port Royal Sound also represented a divergence from the board's original plan. They had stated a preference for an attack on St. Helena Sound, which was nearer to Charleston and also would have been harder for the Rebels to defend. The natural advantages of Port Royal were so great, however, that the administration chose to take it. Perhaps ironically, Captain (by then Flag Officer) Du Pont was selected to lead the naval contingent in the expedition against the harbor.[6]

The Gulf blockade diverged much further from board plans for several reasons. One of the most important is the lack of knowledge of the Gulf coast compared with the Atlantic. The hydrography was so imperfectly known that one of the board's more emphatic recommendations was that a Coast Survey vessel should be attached to each blockading squadron.[7] This recommendation was accepted. The Coast Survey proved to be quite useful throughout the war.

Although Ship Island was taken in accord with the report of August 9, the Navy Department used it as the staging ground for David G. Farragut's assault on and capture of New Orleans. The board had opposed any immediate move up the Mississippi River, not because it would be undesirable, but because they believed that it could not be done with the weapons at hand.[8]

The blockade of the southern extreme of the Texas coast also did not conform to board expectations. The problem there was that the port at Brownsville, at the mouth of the Rio Grande, also served the Mexican community of Matamoros. The international problems associated with the blockade there were exacerbated by a rebellion underway at that time in Mexico against Emperor Maximilian.[9]

Although it may appear that the Blockade Strategy Board had only a minimal effect on the war, it nevertheless deserves respect because it was the first effort by the United States to conduct a war by rational principles, rather than simply reacting to events. As the armed forces did not have an Office of Naval Operations or a General Staff at the time, it served as a rudimentary surrogate. As such, it was an important forerunner of the present-day staff system.

See also

[edit]- Union Navy

- Confederate States Navy

- Blockade runners of the American Civil War

- Blockade mail of the Confederacy

- Bibliography of American Civil War naval history

References

[edit]- ^ Civil War naval chronology, 1861–1865, pp. I-9, I-12.

- ^ Tucker, Blue and Gray Navies, p. 1.

- ^ Reed, Combined operations, p. 7; ORN I, v. 12, p. 195.

- ^ Reed, Combined operations,, pp. 12-21.

- ^ Official Records, Navies I, v. 12, pp. 198-201.

- ^ Browning, Success is all that was expected, pp. 23-41.

- ^ Official Records, Navies I, v. 16, p. 655.

- ^ Official Records, Navies I, volume 16, pages 618-630.

- ^ Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy, pp. 183-186.

- Official records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series I: 27 volumes. Series II: 3 volumes. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894-1922.

- The War of the Rebellion: A compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I: 53 volumes. Series II: 8 volumes. Series III: 5 volumes. Series IV: 4 volumes. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1886-1901.

- United States Navy Department, Naval History Division, Civil War naval chronology, 1861–1865. Government Printing Office, 1971.

- Browning, Robert M., Success is all that was expected : the South Atlantic blockading squadron during the Civil War. Washington, D.C. : Brassey's, 2002. ISBN 1-57488-514-6

- Reed, Rowena, Combined operations in the Civil War. United States Naval Institute, 1978. ISBN 0-87021-122-6

- Tucker, Spencer C., Blue and Gray Navies; the Civil War afloat. Naval Institute, 2006. ISBN 1-59114-882-0

- Wise, Stephen R., Lifeline of the Confederacy: blockade running during the Civil War. University of South Carolina, 1988.