Personal name

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2010) |

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

A personal name, full name or prosoponym (from Ancient Greek prósōpon – person, and onoma –name)[1] is the set of names by which an individual person or animal is known, and that can be recited as a word-group, with the understanding that, taken together, they all relate to that one individual.[2] In many cultures, the term is synonymous with the birth name or legal name of the individual. In linguistic classification, personal names are studied within a specific onomastic discipline, called anthroponymy.[3] As of 2023, aside from humans, dolphins and elephants have been known to use personal names.

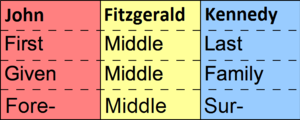

In Western culture, nearly all individuals possess at least one given name (also known as a first name, forename, or Christian name), together with a surname (also known as a last name or family name). In the name "James Smith", for example, James is the first name and Smith is the surname. Surnames in the West generally indicate that the individual belongs to a family, a tribe, or a clan, although the exact relationships vary: they may be given at birth, taken upon adoption, changed upon marriage, and so on. Where there are two or more given names, typically only one (in English-speaking cultures usually the first) is used in normal speech.

Another naming convention that is used mainly in the Arabic culture and in different other areas across Africa and Asia is connecting the person's given name with a chain of names, starting with the name of the person's father and then the father's father and so on, usually ending with the family name (tribe or clan name). However, the legal full name of a person usually contains the first three names (given name, father's name, father's father's name) and the family name at the end, to limit the name in government-issued ID. Men's names and women's names are constructed using the same convention, and a person's name is not altered if they are married.[4]

Some cultures, including Western ones, also add (or once added) patronymics or matronymics, for instance as a middle name as with Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (whose father's given name was Ilya), or as a last name as with Björk Guðmundsdóttir (whose father is named Guðmundur) or Heiðar Helguson (whose mother was named Helga). Similar concepts are present in Eastern cultures. However, in some areas of the world, many people are known by a single name, and so are said to be mononymous. Still other cultures lack the concept of specific, fixed names designating people, either individually or collectively. Certain isolated tribes, such as the Machiguenga of the Amazon, do not use personal names.[i]

A person's personal name is usually their full legal name; however, some people use only part of their full legal name, a title, nickname, pseudonym or other chosen name that is different from their legal name, and reserve their legal name for legal and administrative purposes.

It is nearly universal for people to have names; the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child declares that a child has the right to a name from birth.[7]

Structure in humans[edit]

Common components of names given at birth can include:

- Personal name: The given name (or acquired name in some cultures) can precede a family name (as in most European cultures), or it can come after the family name (as in some East Asian cultures and Hungary), or be used without a family name.

- Patronymic: A surname based on the given name of the father.

- Matronymic: A surname based on the given name of the mother.

- Family name: A name used by all members of a family. In China, surnames gradually came into common use beginning in the 3rd century BC (having been common only among the nobility before that). In some areas of East Asia (e.g. Korea and Vietnam), surnames developed in the next several centuries, while in other areas (like Japan), surnames did not become prevalent until the 19th century. In Europe, after the loss of the Roman system, the common use of family names started quite early in some areas (France in the 13th century, and Germany in the 16th century), but it often did not happen until much later in areas that used a patronymic naming custom, such as the Scandinavian countries, Wales, and some areas of Germany, as well as Russia and Ukraine. The compulsory use of surnames varied greatly. France required a priest to write surnames in baptismal records in 1539 (but did not require surnames for Jews, who usually used patronymics, until 1808). On the other hand, surnames were not compulsory in the Scandinavian countries until the 19th or 20th century (1923 in Norway), and Iceland still does not use surnames for its native inhabitants. In most of the cultures of the Middle East and South Asia, surnames were not generally used until European influence took hold in the 19th century.

In Spain and most Latin American countries, two surnames are used, one being the father's family name and the other being the mother's family name. In Spain, the second surname is sometimes informally used alone if the first one is too common to allow an easy identification. For example, former Spanish Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero is often called just Zapatero. In Argentina, only the father's last name is used, in most cases.

In Portugal, Brazil and most other Portuguese-speaking countries, at least two surnames are used, often three or four, typically some or none inherited from the mother and some or all inherited from the father, in that order. Co-parental siblings most often share an identical string of surnames. For collation, shortening, and formal addressing, the last of these surnames is typically preferred. A Portuguese person named António de Oliveira Guterres would therefore be known commonly as António Guterres.

In Russia, the first name and family name conform to the usual Western practice, but the middle name is patronymic. Thus, all the children of Ivan Volkov would be named "[first name] Ivanovich Volkov" if male, or "[first name] Ivanovna Volkova" if female (-ovich meaning "son of", -ovna meaning "daughter of",[8] and -a usually being appended to the surnames of girls). However, in formal Russian name order, the surname comes first, followed by the given name and patronymic, such as "Raskolnikov Rodion Romanovich".[9]

In many families, single or multiple middle names are simply alternative names, names honoring an ancestor or relative, or, for married women, sometimes their maiden names. In some traditions, however, the roles of the first and middle given names are reversed, with the first given name being used to honor a family member and the middle name being used as the usual method to address someone informally. Many Catholic families choose a saint's name as their child's middle name or this can be left until the child's confirmation when they choose a saint's name for themselves. Cultures that use patronymics or matronymics will often give middle names to distinguish between two similarly named people: e.g., Einar Karl Stefánsson and Einar Guðmundur Stefánsson. This is especially done in Iceland (as shown in example) where people are known and referred to almost exclusively by their given name/s.

Some people (called anonyms) choose to be anonymous, that is, to hide their true names, for fear of governmental prosecution or social ridicule of their works or actions. Another method to disguise one's identity is to employ a pseudonym.

For some people, their name is a single word, known as a mononym. This can be true from birth, or occur later in life. For example, Teller, of the magician duo Penn and Teller, was named Raymond Joseph Teller at birth, but changed his name both legally and socially to be simply "Teller". In some official government documents, such as his driver's license, his given name is listed as NFN, an initialism for "no first name".

The Inuit believe that the souls of the namesakes are one, so they traditionally refer to the junior namesakes, not just by the names (atiq), but also by kinship title, which applies across gender and generation without implications of disrespect or seniority.

In Judaism, someone's name is considered intimately connected with their fate, and adding a name (e.g. on the sickbed) may avert a particular danger. Among Ashkenazi Jews it is also considered bad luck to take the name of a living ancestor, as the Angel of Death may mistake the younger person for their namesake (although there is no such custom among Sephardi Jews). Jews may also have a Jewish name for intra-community use and use a different name when engaging with the Gentile world.

Chinese and Japanese emperors receive posthumous names.

In some Polynesian cultures, the name of a deceased chief becomes taboo. If he is named after a common object or concept, a different word has to be used for it.

In Cameroon, there is "a great deal of mobility" within naming structure. Some Cameroonians, particularly Anglophone Cameroonians, use "a characteristic sequencing" starting with a first surname, followed by a forename then a second surname (e.g. Awanto Josephine Nchang), while others begin with a forename followed by first and then second surnames (e.g. Josephine Awanto Nchang). The latter structure is rare in Francophone Cameroon, however, where a third structure prevails: First surname, second surname, forename (e.g. Awanto Nchang Josephine).[10]

Depending on national convention, additional given names (and sometimes titles) are considered part of the name.

Feudal names[edit]

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (February 2013) |

The royalty, nobility, and gentry of Europe traditionally have many names, including phrases for the lands that they own. The French developed the method of putting the term by which the person is referred in small capital letters. It is this habit which transferred to names of Eastern Asia, as seen below. An example is that of Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch Gilbert du Motier, who is known as the Marquis de La Fayette. He possessed both the lands of Motier and La Fayette.

The bare place name was used formerly to refer to the person who owned it, rather than the land itself (the word "Gloucester" in "What will Gloucester do?" meant the Duke of Gloucester). As a development, the bare name of a ship in the Royal Navy meant its captain (e.g., "Cressy didn't learn from Aboukir") while the name with an article referred to the ship (e.g., "The Cressy is foundering").

Naming conventions[edit]

A personal naming system, or anthroponymic system, is a system describing the choice of personal name in a certain society. Personal names consist of one or more parts, such as given name, surname and patronymic. Personal naming systems are studied within the field of anthroponymy.

In contemporary Western societies (except for Iceland, Hungary, and sometimes Flanders, depending on the occasion), the most common naming convention is that a person must have a given name, which is usually gender-specific, followed by the parents' family name. In onomastic terminology, given names of male persons are called andronyms (from Ancient Greek ἀνήρ / man, and ὄνομα / name),[11] while given names of female persons are called gynonyms (from Ancient Greek γυνή / woman, and ὄνομα / name).[12]

Some given names are bespoke, but most are repeated from earlier generations in the same culture. Many are drawn from mythology, some of which span multiple language areas. This has resulted in related names in different languages (e.g. George, Georg, Jorge), which might be translated or might be maintained as immutable proper nouns.

In earlier times, Scandinavian countries followed patronymic naming, with people effectively called "X's son/daughter"; this is now the case only in Iceland and was recently re-introduced as an option in the Faroe Islands. It is legally possible in Finland as people of Icelandic ethnic naming are specifically named in the name law. When people of this name convert to standards of other cultures, the phrase is often condensed into one word, creating last names like Jacobsen (Jacob's Son).

There is a range of personal naming systems:[13]

- Binomial systems: apart from their given name, people are described by their surnames, which they obtain from one of their parents. Most modern European personal naming systems are of this type.

- Patronymic systems: apart from their given name, people are described by their patronymics, that is, given names (not surnames) of parents or other ancestors. Such systems were in wide use throughout Europe in the first millennium CE, but were replaced by binomial systems. The Icelandic system is still patronymic.

- More complex systems like Arabic system, consisting of paedonymic (son's name), given name, patronymic and one or two bynames.

Different cultures have different conventions for personal names.

English-speaking countries[edit]

Generational designation[edit]

When names are repeated across generations, the senior or junior generation (or both) may be designed with the name suffix "Sr." or "Jr.", respectively (in the former case, retrospectively); or, more formally, by an ordinal Roman number such as "I", "II" or "III". In the Catholic tradition, papal names are distinguished in sequence, and may be reused many times, such as John XXIII (the 23rd pope assuming the papal name "John").

In the case of the American presidents George H. W. Bush and his son George W. Bush, distinct middle initials serve this purpose instead, necessitating their more frequent use. The improvised and unofficial "Bush Sr." and "Bush Jr." were nevertheless tossed about in banter on many entertainment journalism opinion panels; alternatively, they became distinguished merely as "W." and "H. W.".

Rank, title, honour, accreditation, and affiliation[edit]

In formal address, personal names may be preceded by pre-nominal letters, giving title (e.g. Dr., Captain), or social rank, which is commonly gendered (e.g. Mr., Mrs., Ms., Miss.) and might additionally convey marital status. Historically, professional titles such as "Doctor" and "Reverend" were largely confined to male professions, so these were implicitly gendered.

In formal address, personal names, inclusive of a generational designation, if any, may be followed by one or more post-nominal letters giving office, honour, decoration, accreditation, or formal affiliation.

Name order[edit]

Western name order[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

The order given name(s), family name is commonly known as the Western name order and is usually used in most European countries and in non-European countries that have cultures predominantly influenced by Europe (e.g. the United States, Brazil, Australia, and New Zealand). It is also used in non-Western regions such as North, East, Central and West India; Pakistan; Bangladesh; Thailand; Saudi Arabia; Indonesia (non-traditional); Singapore; Malaysia (most of, non-traditional); and the Philippines.

Within alphabetic lists and catalogs, however, the family name is generally put first, with the given name(s) following and separated by a comma (e.g. Jobs, Steve), representing the "lexical name order". This convention is followed by most Western libraries, as well as on many administrative forms. In some countries, such as France,[15] or countries previously part of the former Soviet Union, the comma may be dropped and the swapped form of the name be uttered as such, perceived as a mark of bureaucratic formality. In the USSR and now Russia, personal initials are often written in the "family name - given name - patronymic name" order when signing official documents (Russian: ФИО, romanized: FIO), e.g. "Rachmaninoff S.V.".

Eastern name order[edit]

The order family name, given name, commonly known as the Eastern name order, began to be prominently used in Ancient China[16] and subsequently influenced the East Asian cultural sphere (China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam) and particularly among the Chinese communities in Cambodia, Laos, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, or the Philippines. It is also used in the southern and northeastern parts of India, as well as in Central Europe by Hungarians. In Uganda, the ordering "traditional family name first, Western origin given name second" is also frequently used.[17]

When East Asian names are transliterated into the Latin alphabet, some people prefer to convert them to the Western order, while others leave them in the Eastern order but write the family name in capital letters. To avoid confusion, there is a convention in some language communities, e.g., French, that the family name should be written in all capitals when engaging in formal correspondence or writing for an international audience. In Hungarian, the Eastern order of Japanese names is officially kept, and Hungarian transliteration is used (e.g. Mijazaki Hajao in Hungarian), but Western name order is also sometimes used with English transliteration (e.g. Hayao Miyazaki).

Starting from the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the Western name order was primarily used among the Japanese nobility when identifying themselves to non-Asians with their romanized names. As a result, in popular Western publications, this order became increasingly used for Japanese names in the subsequent decades.[18] In 2020, the Government of Japan reverted the Westernized name order back to the Eastern name order in official documents (e.g. identity documents, academic certificates, birth certificates, marriage certificates, among others), which means writing family name first in capital letters and has recommended that the same format be used among the general Japanese public.[19]

Japan has also requested Western publications to respect this change, such as not using Shinzo Abe but rather Abe Shinzo, similar to how Chinese leader Xi Jinping is not referred to as Jinping Xi.[20] Its sluggish response by Western publications was met with ire by Japanese politician Taro Kono, who stated that "If you can write Moon Jae-in and Xi Jinping in correct order, you can surely write Abe Shinzo the same way."[21]

East Asia[edit]

Chinese, Koreans, and other East Asian peoples, except for those traveling or living outside of China and areas influenced by China, rarely reverse their Chinese and Korean language names to the Western naming order. Western publications also preserve this Eastern naming order for Chinese, Korean and other East Asian individuals, with the family name first, followed by the given name.[22]

Chinese[edit]

In China, Cantonese names of Hong Kong people are usually written in the Eastern order with or without a comma (e.g. Bai Chiu En or Bai, Chiu En). Outside Hong Kong, they are usually written in Western order. Unlike other East Asian countries, the syllables or logograms of given names are not hyphenated or compounded but instead separated by a space (e.g. Chiu En). Outside East Asia, it is often confused with the second syllables with middle names regardless of name order. Some computer systems could not handle given name inputs with space characters.

Some Chinese, Malaysians and Singaporeans may have an anglicised given name, which is always written in the Western order. The English and transliterated Chinese full names can be written in various orders. A hybrid order is preferred in official documents including the legislative records in the case for Hong Kong.

Examples of the hybrid order goes in the form of Hong Kong actor “Tony Leung Chiu-wai” or Singapore Prime Minister "Lawrence Wong Shyun Tsai", with family names (in the example, Leung and Wong) shared in the middle. Therefore, the anglicised names are written in the Western order (Tony Leung, Lawrence Wong) and the Chinese names are written in the Eastern order (Leung Chiu-wai, 梁朝偉; Wong Shyun Tsai, 黄循财).

Japanese[edit]

Japanese use the Eastern naming order (family name followed by given name). In contrast to China and Korea, due to familiarity, Japanese names of contemporary people are usually "switched" when people who have such names are mentioned in media in Western countries; for example, Koizumi Jun'ichirō is known as Junichiro Koizumi in English. Japan has requested that Western publications cease this practice of placing their names in the Western name order and revert to the Eastern name order.[19]

Mongolian[edit]

Mongols use the Eastern naming order (patronymic followed by given name), which is also used there when rendering the names of other East Asians. However, Russian and other Western names (with the exception of Hungarian names) are still written in Western order.

South India[edit]

Telugu[edit]

Telugu people from Andhra Pradesh and Telangana traditionally use family name, given name order.[23] The family name first format is different from North India where family name typically appears last or other parts of South India where patronymic names are widely used instead of family names.[24]

Tamil[edit]

Tamil people, generally those of younger generations, do not employ caste names as surnames. This came into common use in India and also the Tamil diaspora in nations like Singapore after the Dravidian movement in 1930s, when the Self respect movement in the 1950s and 1960s campaigned against the use of one's caste[25][26] as part of the name. Patronymic naming system is: apart from their given name, people are described by their patronymic, that is given names (not surnames) of their father. Older generations used the initials system where the father's given name appears as an initial, for eg: Tamil Hindu people's names simply use initials as a prefix instead of Patronymic suffix (father's given name) and the initials is/ are prefixed or listed first and then followed by the son's/ daughter's given name.

| Person's

given name |

Father's

given name |

Patronymic initials prefix

naming system |

Patronymic suffix

naming system |

Meaning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Rajeev | Suresh | S. Rajeev | Rajeev Suresh | Rajeev son of Suresh |

| Female | Meena | Suresh | S. Meena | Meena Suresh | Meena daughter of Suresh |

One system used for naming,[27] using only given names (without using family name or surname) is as below: for Tamil Hindu son's name using the initials[28] system: S. Rajeev: (initial S for father's given name Suresh and Rajeev is the son's given name). The same Tamil Hindu name using Patronymic suffix last name system is Rajeev Suresh meaning Rajeev son of Suresh (Rajeev (first is son's given name) followed by Suresh (father's given name)). As a result, unlike surnames, while using patronymic suffix the same last name will not pass down through many generations. For Tamil Hindu daughters, the initials naming[27] system is the same, eg: S. Meena. Using the Patronymic suffix system it is Meena Suresh: meaning Meena daughter of Suresh; Meena (first is daughter's given name) followed by Suresh (father's given name). As a result, unlike surnames, while using patronymic suffix the same last name will not pass down through many generations. And after marriage[29] the wife may or may not take her husband's given name as her last name instead of her father's. Eg: after marriage, Meena Jagadish: meaning Meena wife of Jagadish: Meena (first is wife's given name) followed by Jagadish (husband's given name).

Hungary[edit]

Hungary is one of the few Western countries to use the Eastern naming order where the given name is placed after the family name.[30]

Mordvin[edit]

Mordvins use two names – a Mordvin name and a Russian name. The Mordvin name is written in the Eastern name order. Usually, the Mordvin surname is the same as the Russian surname, for example Sharononj Sandra (Russian: Aleksandr Sharonov), but it can be different at times, for example Yovlan Olo (Russian: Vladimir Romashkin).

South Estonian[edit]

In South Estonian the names are written in the Eastern name order.

Non-human personal names[edit]

Animal names for each other[edit]

Humans are not the only animals that use personal names. In a 2006 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences researchers from the University of North Carolina Wilmington studying bottlenose dolphins in Sarasota Bay, Florida, found that the dolphins had names for each other.[31] A dolphin chooses its name as an infant.[32]

According to a 2024 article of a study of elephant calls in Amboseli National Park, Kenya and Samburu National Reserve and Buffalo Springs National Reserves between 1986 and 2022 done with machine learning, elephants learn, recognize and use individualized name-like calls.[33]

Pets[edit]

The practice of naming pets dates back at least to the 23rd century BC; an Egyptian inscription from that period mentions a dog named Abuwtiyuw (𓂝𓃀𓅱𓅂𓃡).[34]

Many pet owners give human names to their pets. This has been shown to reflect the owner having a human-like relationship with the pet.[35] The name given to a pet may refer to its appearance[35] or personality,[35] or be chosen for endearment,[35] or in honor of a favorite celebrity.[36] Pet names often reflect the owner's view of the animal, and the expectations they may have for it.[37][38]

Dog breeders often choose specific themes for their names, sometimes based on the number of the litter.[39] In some countries, like Germany or Austria, names are chosen alphabetically, with names starting with 'A' for puppies from the first litter, 'B' for the second litter, and so on. A puppy called "Dagmar" would belong to a fourth litter. Dog owners can choose to keep the original name, or rename their pet.[40]

It has been argued that the giving of names to their pets allows researchers to view their pets as ontologically different from unnamed laboratory animals with which they work.[41]

Humans[edit]

Apart from the Linnaean taxonomy, some humans give individual non-human animals and plants names, usually of endearment.[citation needed] In onomastic classification, names of individual animals are called zoonyms,[42] while names of individual plants are called phytonyms.[43]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Keats-Rohan 2007, p. 164-165.

- ^ Room 1996, p. 79.

- ^ Room 1996, p. 8.

- ^ Notzon, Beth; Nesom, Gayle (February 2005). "The Arabic Naming System" (PDF). Science Editor. 28 (1): 20–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2022.

- ^ Snell, Wayne W. (1964). Kinship relations in Machiguenga. Hartford Seminary Foundation. pp. 17–25.

- ^ Johnson, Allen W. (2003). Families of the forest: the Matsigenka Indians of the Peruvian Amazon. University of California Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-520-23242-6.

- ^ Text of the Convention on the Rights of the Child Archived 13 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989 entry into force 2 September 1990, in accordance with article 49, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- ^ "Russian Names". Russland Journal. October 2007. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Baiburin, Albert. "Как появилась формула "фамилия — имя — отчество"" ["How the formula of surname-given name-patronymic came to be]. Arzamas Academy (in Russian). Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ Kouega, Jean-Paul (2007). "Forenames in Cameroon English speech" (PDF). The International Journal of Language Society and Culture (23): 33. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2024. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ Room 1996, p. 6.

- ^ Barolini 2005, p. 91, 98.

- ^ Hanks, Patrick; Parkin, Harry (2016). "Family names". In Carole Hough (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 214. ISBN 9780191630415.

- ^ A Magyar helyesírás Elvei és szabályai (1879). at Google Books

- ^ "Culture(s) / Giving your surname and given name in the correct order". TV5MONDE: learn French. Archived from the original on 15 November 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ "Chinese Culture". culturalatlas.sbs.com.au. Cultural Atlas. January 2021. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ What order of your name(s) says about state of our education system Archived 21 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine and Part 2 Archived 21 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Daily Monitor May 2019

- ^ Saeki, Shizuka (2001). First Name Terms. Vol. 47. Look Japan. p. 35. Archived from the original on 27 June 2002.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "公用文等における日本人の姓名のローマ字表記について" (PDF) (Press release). 文化庁国語課. 25 October 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ James Griffiths (22 May 2019). "Japan wants you to say its leader's name correctly: Abe Shinzo". CNN. Archived from the original on 22 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ Tiezzi, Shannon (3 September 2020). "Abe Shinzo or Shinzo Abe: What's in a Name?". thediplomat.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ Terry, Edith (2002). How Asia Got Rich: Japan, China and the Asian Miracle. M.E. Sharpe. p. 632. ISBN 9780765603562.

- ^ Brown, Charles Philip (1857). A Grammar of the Telugu Language. printed at the Christian Knowledge Society's Press. p. 209.

- ^ Agency, United States Central Intelligence (1964). Telugu Personal Names. Central Intelligence Agency. p. 5.

- ^ Krishnaswamy, M. V. (2002). In Quest of Dravidian Roots in South Africa. International School of Dravidian Linguistics. p. 274. ISBN 978-81-85692-32-6. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Solomon, John (31 March 2016). A Subaltern History of the Indian Diaspora in Singapore: The Gradual Disappearance of Untouchability 1872-1965. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-35380-5. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Note:*M. Karunanidhi is a former Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu. He uses the initials system for his name. His given name is Karunanidhi, his father's given name is Muthuvel, he uses as his name M. Karunanidhi.

Note: *M.Karunanidhi's daughter Kanimozhi Karunanidhi uses the patronymic suffix naming system. Her given name is Kanimozhi, her father's given name is Karunanidhi, she uses as her name: Kanimozhi Karunanidhi.

- ^ S. A., Hariharan (4 April 2010). "First name, middle name, surname... real name?". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Sharma, Kalpana (6 March 2010). "The Other Half: What's in a name?". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Sarkadii, Zsuzsanna (26 August 2022). "Hungarian Names: A Quick Guide". Hungarian Citizenship.

- ^ "Dolphins, like humans, recognize names, May 9, 2006,CNN". CNN. Archived from the original on 2 June 2006.

- ^ Carey, Bjorn (May 2006). "Dolphins Name Themselves". Live Science. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- ^ Pardo, Michael A.; Fristrup, Kurt; Lolchuragi, David S.; Poole, Joyce H.; Granli, Petter; Moss, Cynthia; Douglas-Hamilton, Iain; Wittemyer, George (10 June 2024). "African elephants address one another with individually specific name-like calls". Nature Ecology & Evolution: 1–12. doi:10.1038/s41559-024-02420-w. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 38858512.

- ^ Reisner, George Andrew (December 1936). "The Dog Which Was Honored by the King of Upper and Lower Egypt". Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts. 34 (206): 96–99. JSTOR 4170605.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Eldridge 2003.

- ^ Lyons, Margaret (28 September 2009). "What celebrity would you name your pet after?". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- ^ McGillivray, Debbie; Adamson, Eve (2004). The complete idiot's guide to pet psychic communication. Alpha Books. ISBN 1-59257-214-6.

- ^ Adamson, Eve (13 October 2005). Adopting a Pet For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 10. ISBN 9780471785125.

- ^ Reisen, Jan (5 October 2017). "What's in a Name? Breeders Share How They Pick Perfect Puppy Names". akc.org. American Kennel Club. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ "Der perfekte Hundename – mit Tipps und Beispielen zum Ergebnis" [The perfect dog name - with tips and examples]. fressnapf.at (in German). Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Phillips, Mary T. (1994). "Proper names and the social construction of biography: The negative case of laboratory animals". Qualitative Sociology. 17 (2). SpringerLink: 119–142. doi:10.1007/BF02393497. S2CID 143506107.

- ^ Room 1996, p. 106.

- ^ Room 1996, p. 80.

Sources[edit]

- Barolini, Teodolinda, ed. (2005). Medieval Constructions in Gender And Identity: Essays in Honor of Joan M. Ferrante. Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. ISBN 9780866983372.

- Bruck, Gabriele vom; Bodenhorn, Barbara, eds. (2009) [2006]. An Anthropology of Names and Naming (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.[permanent dead link]

- Fraser, Peter M. (2000). "Ethnics as Personal Names". Greek Personal Names: Their Value as Evidence (PDF). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 149–157. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Keats-Rohan, Katharine, ed. (2007). Prosopography Approaches and Applications: A Handbook. Oxford: Unit for Prosopographical Research. ISBN 9781900934121.

- Room, Adrian (1996). An Alphabetical Guide to the Language of Name Studies. Lanham and London: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810831698. Archived from the original on 9 June 2024. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- Eldridge, Wayne B. (2003). The Best Pet Name Book Ever!. Barron's Educational Series, Incorporated. ISBN 9780764181337.

Further reading[edit]

- Matthews, Elaine; Hornblower, Simon; Fraser, Peter Marshall, Greek Personal Names: Their Value as Evidence, Proceedings of the British Academy (104), Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-19-726216-3

External links[edit]

- Varying use of first and family names in different countries and cultures

- Falsehoods Programmers Believe About Names

- Lexicon of Greek Personal Names, contains over 35,000 published Greek names.