King's Observatory

| The King's Observatory | |

|---|---|

| Kew Observatory | |

The King's Observatory in winter | |

| Location | Old Deer Park |

| Nearest city | Richmond, London |

| Coordinates | 51°28′08″N 0°18′53″W / 51.4689°N 0.3147°W |

| Built | 1769 |

| Built for | George III of the United Kingdom |

| Original use | Astronomical and terrestrial magnetic observatory |

| Current use | Private dwelling |

| Architect | Sir William Chambers |

| Owner | Crown Estate |

| Website | www |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Kew Observatory |

| Designated | 10 January 1950 |

| Reference no. | 1357729 |

The King's Observatory (called for many years the Kew Observatory)[1] is a Grade I listed building[2] in Richmond, London. Now a private dwelling, it formerly housed an astronomical and terrestrial magnetic observatory[3] founded by King George III. The architect was Sir William Chambers; his design of the King's Observatory influenced the architecture of two Irish observatories – Armagh Observatory and Dunsink Observatory near Dublin.[4]

Location

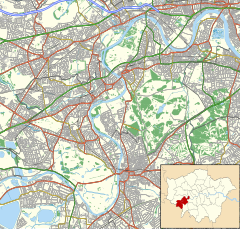

[edit]The observatory and its grounds are located within the grounds of the Royal Mid-Surrey Golf Club, which is part of the Old Deer Park of the former Richmond Palace in Richmond, historically in Surrey and now in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. The former royal manor of Kew lies to the immediate north. The observatory grounds overlie to the south the site of the former Sheen Priory, the Carthusian monastery established by King Henry V in 1414.[5] The observatory is not publicly accessible, and obscuring woodlands mean that it cannot be viewed from outside the golf course, which is not open to the general public.

People

[edit]Directors (superintendents) of the observatory included Stephen Demainbray, Francis Ronalds, John Welsh, Balfour Stewart, Francis John Welsh Whipple, Charles Chree, and George Clarke Simpson.

History

[edit]The observatory was completed in 1769,[6] in time for King George III's observation of the transit of Venus that occurred on 3 June in that year. It was located close to Richmond Lodge,[7] the country residence of the royal family between 1764 and 1771.[8]

In 1842, the by then empty building was taken on by the British Association for the Advancement of Science and became widely known as the Kew Observatory.[9] Francis Ronalds was the inaugural Honorary Director for the next decade and founded the observatory's enduring reputation.

Responsibility for the facility was transferred to the Royal Society in 1871. The National Physical Laboratory was established there in 1900 and from 1910 it housed the Meteorological Office. The Met Office closed the observatory in 1980. The geomagnetic instruments had already been relocated to Eskdalemuir Observatory in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland in 1908 after the advent of electrification in London led to interference with their operations.[10]

Scientific achievements

[edit]Observing the transit of Venus on 3 June 1769

[edit]

A contemporary report by Stephen Demainbray, the superintendent of the observatory, says: "His Majesty the King who made his observation with a Shorts reflecting telescope, magnifying Diameters 170 Times, was the first to view the Penumbra of Venus touching the Edge of the Sun's Disk. The exact mean time (according to civil Reckoning) was attended to by Stephen Demainbray, appointed to take exact time by Shelton's Regulator, previously regulated by several astronomical observations."[11]

Self-registering instruments

[edit]Francis Ronalds invented many meteorological, magnetic and electrical instruments at Kew, which saw long-term use around the world. These included the first successful cameras in 1845 to record the variations of parameters such as atmospheric pressure, temperature, humidity, atmospheric electricity and geomagnetism through the day and night.[12] His photo-barograph was used by Robert Fitzroy from 1862 in making the UK's first official weather forecasts at the Meteorological Office. The network of observing stations set-up in 1867 by the Met Office to assist in understanding the weather was equipped with his cameras – some of these remained in use at Kew until the observatory's closure in 1980.[13]

Atmospheric electricity observations

[edit]Ronalds also established a sophisticated atmospheric electricity observing system at Kew with a long copper rod protruding through the dome of the observatory and a suite of novel electrometers and electrographs to manually record the data. He supplied this equipment to facilities in England, Spain, France, Italy, India (Colaba and Trivandrum) and the Arctic with the goal of delineating atmospheric electricity on a global scale.[14] At Kew, two-hourly data was recorded in the Reports of the British Association between 1844 and 1847.

An entirely new system, providing continuous automatic recording, was installed by Lord Kelvin personally in the early 1860s. This device, based on Kelvin's water dropper potential equaliser with photographic recording,[15] was known as the Kew electrograph. It provided the backbone of a long and almost continuous series of potential gradient measurements which finished in 1980. A secondary system of measurement, operating on different principles, was designed and implemented by the Nobel laureate CTR Wilson, from which records begin in 1906 until the closure of the Observatory.[16] These measurements, which complement those of the Kelvin electrograph, were made on fine days at 1500 GMT. Beyond their applications in atmospheric electricity, the electrograph and Wilson apparatus have been shown to be useful for reconstructing past air pollution changes.[17]

Testing timepiece movements

[edit]In the early 1850s, the facility began performing a role in assessing and rating barometers, thermometers, chronometers, watches, sextants and other scientific instruments for accuracy; this duty was transferred to the National Physical Laboratory in 1910. An instrument which passed the tests was awarded a "Kew Certificate", a hallmark of excellence.[18]

As marine navigation adopted the use of mechanical timepieces, their accuracy became more important. The need for precision resulted in the development of a testing regime involving various astronomical observatories. In Europe, Neuchâtel Observatory, Geneva Observatory, Besançon Astronomical Observatory and Kew were examples of prominent observatories that tested timepiece movements for accuracy. The testing process lasted for many days, typically 45. Each movement was tested in five positions and two temperatures, in ten series of four or five days each. The tolerances for error were much finer than any other standard, including the modern COSC standard. Movements that passed the stringent tests were issued a certification from the observatory called a Bulletin de Marche, signed by the directeur of the observatory. The Bulletin de Marche stated the testing criteria and the actual performance of the movement. A movement with a Bulletin de Marche from an observatory became known as an Observatory Chronometer, and was issued a chronometer reference number by the observatory.

The role of the observatories in assessing the accuracy of mechanical timepieces was instrumental in driving the mechanical watchmaking industry toward higher and higher levels of accuracy. As a result, modern high quality mechanical watch movements have an extremely high degree of accuracy. However, no mechanical movement could ultimately compare to the accuracy of a quartz movement. Accordingly, such chronometer certification ceased in the late 1960s and early 1970s with the advent of the quartz watch movement.

Later use

[edit]In 1981 the facility was returned to the Crown Estate Commissioners and reverted to its original name, "King’s Observatory". In 1985 the observatory was refurbished and transformed into commercial offices; new brick buildings were added. From 1986 to 2011 it was used by Autoglass (now Belron) as their UK head office.[19] Since 1989 the lease has been held by Robbie Brothers of Kew Holdings Limited.[19]

In 1999, landscape architect Kim Wilkie was commissioned to prepare a master plan linking the observatory's Grade I landscape to Kew Gardens, Syon Park and Richmond. These proposals were accepted by Kew Holdings Limited. In 2014 Richmond upon Thames London Borough Council granted planning permission for the observatory to be used as a private single family dwelling. All auxiliary buildings have been demolished.

The Observatory in art

[edit]

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology in Oxford has a portrait, Peter Rigaud and Mary Anne Rigaud, by the 18th-century painter John Francis Rigaud. His portrait of his nephew and niece, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1778, shows Stephen Peter Rigaud (1774–1839) (who became a mathematical historian and astronomer, and Savilian Chair of Geometry and Savilian Professor of Astronomy at the University of Oxford) and his elder sister. The picture, painted when they were aged four and seven, shows them in a park landscape with the observatory (where their father was observer) in the background.[20] Although described here as Richmond Park, topographical considerations make it more likely that the park portrayed is Old Deer Park, where the observatory is situated.

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Scott, Robert Henry (1885). "The History of the Kew Observatory" in Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Vol. XXXIX. Royal Society. pp. 37–86.

- ^ Historic England (10 January 1950). "Kew Observatory (1357729)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Hunt, Andrew (21 January 2007). "Where a king watched a transit of Venus". Cities of Science. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ "The King's Observatory at Richmond". History. Armagh Observatory. 22 February 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ Diagram on p. 51 of Cloake, John (1990). Richmond's Great Monastery, The Charterhouse of Jesus of Bethlehem of Shene. London: Richmond Local History Society. ISBN 0-9508198-6-7.

- ^ Cherry, Bridget and Pevsner, Nikolaus (1983). The Buildings of England – London 2: South. London: Penguin Books. p. 520. ISBN 0-14-0710-47-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Watkin, David. The Architect King: George III and the Culture of the Enlightenment. Royal Collection, 2004. p.108

- ^ Black, Jeremy. George III: America's Last King. Yale University Press, 2008. p.175

- ^ MacDonald, Lee (2018). Kew Observatory & the evolution of Victorian science, 1840–1910. Pittsburgh, PA. ISBN 9780822983491. OCLC 1038801663.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "A Scientific Workshop Threatened by Applied Science: Kew Observatory to Be Removed Owing To The Disturbance Caused by Electric Traction". The Illustrated London News. 8 August 1903.

- ^ Manuscript of Stephen Demainbray's notebook of the Transit of Venus 1769, "The Observatory: A Monthly Review of Astronomy" (1882) called 'Dr Demainbray and the King's Observatory at Kew'. The manuscript is now held at King's College London and is quoted in "The King's Observatory at Kew & The Transit of Venus 1769". Arcadian Times. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ Ronalds, B. F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-78326-917-4.

- ^ Ronalds, B. F. (2016). "The Beginnings of Continuous Scientific Recording using Photography: Sir Francis Ronalds' Contribution". European Society for the History of Photography. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ Ronalds, B. F. (June 2016). "Sir Francis Ronalds and the Early Years of the Kew Observatory". Weather. 71 (6): 131–134. Bibcode:2016Wthr...71..131R. doi:10.1002/wea.2739. S2CID 123788388.

- ^ Aplin, K. L.; Harrison, R. G. (3 September 2013). "Lord Kelvin's atmospheric electricity measurements". History of Geo- and Space Sciences. 4 (2): 83–95. arXiv:1305.5347. Bibcode:2013HGSS....4...83A. doi:10.5194/hgss-4-83-2013. ISSN 2190-5029. S2CID 9783512.

- ^ Harrison, R. G.; Ingram, W. J. (July 2005). "Air–earth current measurements at Kew, London, 1909–1979". Atmospheric Research. 76 (1–4): 49–64. Bibcode:2005AtmRe..76...49H. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2004.11.022. ISSN 0169-8095.

- ^ Harrison, R. G.; Aplin, K. L. (September 2002). "Mid-nineteenth century smoke concentrations near London". Atmospheric Environment. 36 (25): 4037–4043. Bibcode:2002AtmEn..36.4037H. doi:10.1016/s1352-2310(02)00334-5. ISSN 1352-2310.

- ^ Macdonald, Lee T. (26 November 2018). "University physicists and the origins of the National Physical Laboratory, 1830–1900". History of Science. 59 (1): 73–92. doi:10.1177/0073275318811445. PMID 30474405. S2CID 53792127.

- ^ a b Brothers, Robbie. "Home page". The King's Observatory. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ "John Francis Rigaud (1742–1810): Stephen Peter Rigaud and Mary Anne Rigaud". Browse the Paintings Collection. Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Harris, John (1970). Sir William Chambers: Knight of the Polar Star. London: Zwemmer. ISBN 9780302020760.

- MacDonald, Lee T. Kew Observatory and the Evolution of Victorian Science, 1840–1910. Science and Culture in the Nineteenth Century series. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018. ISBN 978-0-8229-4526-0.

- McLaughlin, Stewart (1992). "The Early History of Kew Observatory" (PDF). Richmond History: Journal of the Richmond Local History Society. 13: 48–49. ISSN 0263-0958. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- Mayes, Julian (2004). "The History of Kew Observatory". Richmond History: Journal of the Richmond Local History Society. 25: 44–57. ISSN 0263-0958.

External links

[edit]- History of the Observatory and Old Deer Park; historical report by John Cloake

- The Observatory and Obelisks, Kew (Old Deer Park)

- Google Books on the "Kew Observatory"

- Google Scholar on the "Kew Observatory"

- Richmond Local History Society

- The National Archives (UK): Records of the Kew Observatory

- Janus: Kew Observatory papers – at the Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives

- 1769 establishments in England

- 1980 disestablishments in England

- Astronomical observatories in England

- Defunct astronomical observatories

- Buildings and structures completed in 1769

- Buildings and structures in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

- Geophysical observatories

- George III

- Grade I listed buildings in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

- History of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

- Met Office

- National Physical Laboratory (United Kingdom)

- Old Deer Park

- Science and technology in London

- William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin