Cookie stuffing

Cookie stuffing is a deceptive tactic in affiliate marketing. In affiliate marketing, individuals (affiliates) are compensated for enticing consumers to buy products through specially crafted URLs that set cookies on users' browsers to track which affiliate referred the user to the site. Affiliates engaging in cookie stuffing use invasive techniques, like pop-up ads, to falsely claiming credit for sales they did not facilitate.

Many affiliate marketing programs prohibit cookie stuffing, considering it fraudulent. It causes retail companies to lose revenue, potentially leading to higher prices for consumers and lost sales for legitimate affiliates. In 2014, Shawn Hogan, a prominent figure in eBay's affiliate program was convicted of wire fraud for engaging in cookie stuffing and received a five-month long federal prison sentence along with a $25,000 fine.[1] However, despite occasional high-profile cases, cookie stuffing remains rare and most users do not encounter it frequently.

Background

[edit]Affiliate marketing is a strategy employed by online giants like GoDaddy, Amazon, and eBay to amplify website traffic.[2] In the framework, third-party entities, or affiliates, receive compensation for promoting the retailer's products, aiming to draw in a more targeted audience and increase sales of products. The entry barrier for affiliates is very low, making affiliate marketing an accessible revenue model for those establishing a website without significant assets or brand recognition. The compensation model for affiliate marketing is predominantly performance-based, operating on a cost-per-sale structure where affiliates are paid only upon the successful purchase of the advertised product.[3] This compensation model serves as a safeguard against potential fraud as it only requires a payment after a confirmed sale.[4] The advantage of affiliate marketing lies in this perceived reduction of fraud risk compared to alternative advertising models. The efficacy of this risk reduction however, hinges on the affiliate's ability to robustly track sales.[5] In reality, tracking by affiliates often falls short, paving the way for deceptive practices such as cookie stuffing.[6][5]

Mechanism

[edit]-

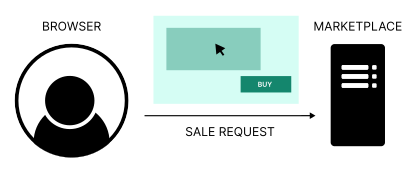

During normal affiliate marketing, a user is typically shown an ad for the product on the affiliate's website

-

If the user clicks on the ad, a request is sent to the marketplace where the user can buy the product

-

During cookie stuffing, the browser is tricked into sending a request to the marketplace without the user's knowledge.

Retailers use third-party cookies to track purchases driven by affiliates. Affiliates place advertisements on their website that contain specially crafted URLs. When users click on the link, a cookie is stored on the user's browser. Later, if the user continues with a purchase from the retailer, the merchant reads this cookie to identify which affiliate will receive a commission for the sale.[7]

Cookie stuffing works by tricking the browser into setting this cookie without the user clicking an affiliate link. Cookie stuffing can be done by embedding web pages in other web pages or via ads that open in separate windows without the user's knowledge. Later, if the user happens to purchase a product on that retailer's website, the retailer will pay a commission for the sale due to the presence of the cookie, even though the affiliate did not drive a sale.[8][9]

Techniques

[edit]Fraudulent affiliate marketers use multiple techniques to perform cookie stuffing. In a 2015 study covering 11,700 domains that had engaged in cookie stuffing, Chachra et al. found that over 91% of websites used redirects.[10] This was manifested in the form of Hyper Text Transfer Protocol (HTTP) redirects (i.e., the use of the 302 and 301 status codes to redirect users to a different domain) or the use of Flash or Javascript to redirect users. Other techniques used by fraudulent affiliates include using iframes to embed the online marketer's website in the code or using scripts and image tags to request specific resources that would set the cookie for the affiliate on the destination website.[3][11]

In the same study, Chachra et al. found that over 84% of cookies set by fraudulent marketers employed referrer obfuscation to hide their activities from retail websites.[12] The referrer header is a HTTP header set by the browser that is often used by affiliates to determine the legitimacy of requests from affiliate marketing websites.[13] Fraudulent marketers would set up websites referencing an image or a Javascript file from an innocuous-looking domain. This domain would then redirect to multiple other domains before arriving at the destination affiliate website. By redirecting the user through several innocuous-looking domains, the fraudulent marketer can trick the browser into setting the wrong website in the referrer header of the request being made to the affiliate website, making it harder for the affiliate marketing firm to track down the source of the request.[12]

Another technique used by some malicious entities includes hijacking or publishing malicious browser extensions on the Chrome and Firefox extension stores. By modifying requests sent to online retailers and setting cookies or redirecting users to affiliate websites on startup, the malicious extension can trick online marketers into thinking that the user legitimately clicked on an affiliate link to navigate to their marketplace.[14][15]

Legality

[edit]Most affiliate marketing programs prohibit cookie stuffing because it tends to undermine genuine product advertising efforts.[16] In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission lays out advertising guidelines mandating the clear disclosure of financial relationships between advertisers and retailers. Cookie stuffing deliberately operates in an opaque manner for users, conflicting with the guidelines that emphasize transparency to the user.[17]

In certain cases in the United States, cookie stuffing has been considered a form of wire fraud. In 2006, when eBay collaborated with the Federal Bureau of Investigation in a sting operation targeting top affiliate marketers, Shawn Hogan, eBay's largest affiliate marketer, was found to have engaged in cookie stuffing.[18] His strategy involved modifying his website to load resources from eBay's servers, thereby setting affiliate cookies on users' browsers. The technique falsely attributed subsequent eBay purchases to Hogan's site.[19] Despite Hogan making over $28 million through eBay's affiliate commissions,[3] it was determined that Hogan's activities did not contribute any substantial revenue to eBay.[19] In subsequent legal proceedings, Hogan pleaded guilty to a single wire fraud charge, leading to a five-month federal prison sentence and a $25,000 fine.[20]

Around the same time, another incident involved eBay's second most prolific affiliate marketer, Brian Dunning, who employed similar tactics to defraud eBay of over $5 million during 2006–2007. Dunning's fraudulent activities came to light as he utilized methods akin to Shawn Hogan's cookie-stuffing scheme.[18] During the legal proceedings, Dunning admitted to collaborating with Hogan in executing the fraud, offering to teach him key techniques. Hogan denied the claim, alleging that Dunning ripped off his techniques. Dunning further alleged that he paid an account manager at an affiliate management network CJ Affiliates, for insider knowledge of how the affiliate network operated, although this claim was not officially confirmed.[21] Dunning, like Hogan, pleaded guilty to a single wire fraud charge and was sentenced to 15 months in prison, followed by three years of supervision.[1]

Impact

[edit]Despite several high-profile cases, only a small number of users encounter cookie stuffing on the web. This has led researchers to infer that the practice of cookie stuffing is confined to a very small group of affiliates.[12] Additionally, cookie stuffing and other forms of affiliate marketing fraud disproportionately impact larger affiliate marketing networks that oversee numerous affiliate marketing programs, as opposed to smaller in-house programs.[22] This is because smaller in-house affiliate programs are motivated by their parent companies to eradicate fraud, given its direct impact on their revenue. On the other hand, larger affiliate marketing networks, which earn a commission only when a transaction occurs between an affiliate and an online marketer, are incentivized not to actively police their programs and to avoid detecting fraudulent practices.[23][24] In certain cases, this behavioral practice has led to online marketers severing ties with affiliate marketing networks.[25]

Cookie stuffing has adverse effects on both end users and legitimate affiliates. For end users, a loss of revenue for the parent online retail company in the form of fraudulent affiliate commission payouts could result in items that would otherwise have been sold at a discount being listed at higher prices to offset the losses incurred by online marketers. Similarly, a decrease in the amount of traffic for an online marketing firm could lead to lower demand and, subsequently, higher prices for items.[26] Legitimate affiliates, who employ advertising to attract consumers, suffer from the impact of cookie stuffing, as they lose out on conversions from affiliate sales that were manipulated as a result of cookie stuffing which overrides legitimate affiliate cookies.[17][26]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b United States Attorney's Office, Northern District of California 2014.

- ^ Snyder & Kanich 2016, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Chachra, Savage & Voelker 2015, p. 41.

- ^ Edelman & Brandi 2013, p. 3.

- ^ a b Edelman & Brandi 2013, p. 1.

- ^ Snyder & Kanich 2016, p. 73.

- ^ Edelman & Brandi 2013, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Chua et al. 2020, p. 11:7.

- ^ Amarasekara, Mathrani & Scogings 2020, pp. 667–668.

- ^ Chachra, Savage & Voelker 2015, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Snyder & Kanich 2016, p. 76.

- ^ a b c Chachra, Savage & Voelker 2015, p. 46.

- ^ Chachra, Savage & Voelker 2015, p. 45.

- ^ Kapravelos et al. 2014, p. 650.

- ^ Orphanides 2019.

- ^ Edelman & Brandi 2013, p. 7.

- ^ a b Chachra, Savage & Voelker 2015, p. 42.

- ^ a b Edwards 2013.

- ^ a b Edelman & Brandi 2013, p. 8.

- ^ Edwards 2014.

- ^ Edelman & Brandi 2013, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Snyder & Kanich 2016, p. 72.

- ^ Chachra, Savage & Voelker 2015, pp. 41, 44.

- ^ Edelman & Brandi 2013, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Edelman & Brandi 2013, p. 15.

- ^ a b Snyder & Kanich 2015, pp. 9–10.

Sources

[edit]- United States Attorney's Office, Northern District of California (18 November 2014). "Laguna Niguel Man Receives Fifteen-Month Prison Term For Defrauding eBay". United States Department of Justice. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- Edwards, Jim (1 March 2014). "eBay's Top Affiliate Marketer Was Just Sentenced To Federal Prison". Business Insider. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- Edwards, Jim (3 May 2013). "How eBay Worked With The FBI To Put Its Top Affiliate Marketers In Prison". Business Insider. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- Kapravelos, Alexandros; Grier, Chris; Chachra, Neha; Kruegel, Christopher; Vigna, Giovanni; Paxson, Vern (2014). Hulk: Eliciting Malicious Behavior in Browser Extensions. USENIX. pp. 641–654. ISBN 978-1-931971-15-7.

- Chua, Mark Yep-Kui; Yee, George O. M.; Gu, Yuan Xiang; Lung, Chung-Horng (29 May 2020). "Threats to Online Advertising and Countermeasures: A Technical Survey". Digital Threats: Research and Practice. 1 (2): 11:1–11:27. doi:10.1145/3374136.

- Amarasekara, Bede; Mathrani, Anuradha; Scogings, Chris (2020). "Stuffing, Sniffing, Squatting, and Stalking: Sham Activities in Affiliate Marketing". Library Trends. 68 (4): 659–678. doi:10.1353/lib.2020.0016. ISSN 1559-0682.

- Snyder, Peter; Kanich, Chris (22 December 2016). "Characterizing fraud and its ramifications in affiliate marketing networks". Journal of Cybersecurity. 2 (1): 71–81. doi:10.1093/cybsec/tyw006. ISSN 2057-2085.

- Edelman, Benjamin G.; Brandi, Wesley (2013). "Risk, Information and Incentives in Online Affiliate Marketing". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2358110. ISSN 1556-5068.

- Chachra, Neha; Savage, Stefan; Voelker, Geoffrey M. (28 October 2015). "Affiliate Crookies: Characterizing Affiliate Marketing Abuse". Proceedings of the 2015 Internet Measurement Conference. IMC '15. Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 41–47. doi:10.1145/2815675.2815720. ISBN 978-1-4503-3848-6.

- Snyder, Peter; Kanich, Chris (2015). "No Please, After You: Detecting Fraud in Affiliate Marketing Networks" (PDF). Workshop on the Economics of Information Security.

- Orphanides, K. G. (28 September 2019). "Chrome extensions are filled with malware. Here's how to stay safe". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 18 June 2024.