Gennett Records

| Gennett Records | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founded | 1917 |

| Founder | Starr Piano Company |

| Defunct | 1947–48 |

| Status | Inactive |

| Genre | Jazz, blues, country |

| Country of origin | U.S. |

| Location | Richmond, Indiana, United States |

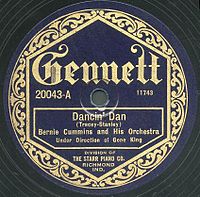

Gennett Records (/dʒəˈnɛt/[1]) was an American record company and label in Richmond, Indiana, United States, which flourished in the 1920s and produced the Gennett, Starr, Champion, Superior, and Van Speaking labels. The company also produced some Supertone, Silvertone, and Challenge records under contract. The firm also pressed, under contract, records for record labels such as Autograph, Rainbow, Hitch, Our Song, and Vaughn; Gennett also pressed records for the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). Gennett produced some of the earliest recordings by Louis Armstrong, King Oliver, Bix Beiderbecke, and Hoagy Carmichael. Its roster also included Jelly Roll Morton, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Charley Patton, and Gene Autry.

History

[edit]Gennett Records was founded in Richmond, Indiana, by the Starr Piano Company in 1917. By the late 1930s, the label had produced more than 16,000 masters.[2] The company had produced early recordings under the green or blue Starr Records label as early as 1915.[3] The new Gennett label was named after Harry, Fred, and Clarence Gennett, brothers and joint managers,[4] and was an attempt to distinguish the label from its parent company and widen distribution beyond Starr piano stores. Early record pressings were outsourced but by October 1917, Starr Valley - home to the Starr Piano manufacturing campus along the Whitewater River - had a six-story phonograph and manufacturing and record-pressing facility.[5] The early issues were vertically cut in the phonograph record grooves, using the hill-and-dale method of a U-shaped groove and sapphire ball stylus, but they switched to the lateral cut method in April 1919.[5][3] Gennett Records rarely paid artists upfront. Some were paid a flat fee, from $15-50 per session, while Black artists received even less. Most artists signed royalty contracts that promised one penny for each copy or side sold.[6][7]

Gennett first set up a recording studio in Manhattan, New York City. Throughout the 1920s, the Manhattan studio saw artists such as Bailey's Lucky Seven, the Original Memphis Five under the pseudonym Ladd's Black Aces, and in November 1924, Louis Armstrong and the Red Onion Jazz Babies.[8] In 1921, the label set up a second studio on the grounds of the piano factory in Richmond under the supervision of Ezra C.A. Wickemeyer, who would manage the studio from August 1921 to mid-1927.[9] The bulk of the labels productions came out of the Richmond studio, which was 125 feet (38 m) long and 30 feet (9.1 m) wide with a control room separated by a double pane of glass. For sound proofing, a Mohawk rug was placed on the floor and drapes and towels were hung on the wall.[10][9] Gennett was one of the few companies to have a recording facility outside of New York, a move which allowed the label to capture Midwestern and Southern artists.[2] Their locality also led to their recordings being appealing to Black individuals and other rural peoples who were largely neglected by the leading New York labels.[11] Some call the Richmond studio the "cradle of recorded jazz."[12]

Gennett recorded early jazz musicians Jelly Roll Morton, Bix Beiderbecke, The New Orleans Rhythm Kings,[4] King Oliver's band with Louis Armstrong, Lois Deppe's Serenaders with Earl Hines,[13] Hoagy Carmichael, Duke Ellington, The Red Onion Jazz Babies, The State Street Ramblers, Zack Whyte and his Chocolate Beau Brummels, Alphonse Trent and his Orchestra and many others. Many of these jazz artists, such as Morton, the Rhythm Kings, and Oliver's band were popular at the Lincoln Gardens and the Friar's Inn nightclubs and had been sent by train to rural Richmond by Chicago, Illinois Starr Piano store manager and talent scout Fred Wiggins.[14][8][15][16] Gennett notably was among the first to record people of color and racially integrated sessions,[3][16] despite over twenty percent of Wayne County's white male population being members of the Ku Klux Klan.[14] Other estimates suggest forty to fifty percent of non-Catholic white men were members of the Richmond klavern.[17]

Throughout the 1920s, Gennett pressed vanity records for the Ku Klux Klan with red labels and gold KKK lettering, often listing performers such as the "100 percent Americans." Klan members politicized hymns with new lyrics, such as "Onward Christian Klansman" for "Onward Christian Soldiers" as well as custom songs such as "Daddy Swiped Our Last Clean Sheet and Joined the Ku Klux Klan."[18][19][15] These private pressings never appeared in Gennett catalogs and were shipped directly to Klan headquarters in Indianapolis after the Klan paid for the records.[18][15] Some of D.C. Stephenson's speeches were recorded by the label.[15] Ironically, Richmond had a large gathering of Ku Klux Klan members in Glen Miller Park followed by a parade on October 5, 1923, the same day King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band, with Louis Armstrong, recorded a second series of discs at the Richmond studio.[18][15] Approximately 30,000 people gathered with Richmond residents to view over 6,000 Klan members participate in a parade.[17] Although the Gennett family was not involved in the Richmond klavern, historian Leonard Moore estimates one of every three native-born white Protestant male in Richmond was a member during this time.[18]

Gennett also recorded early blues and gospel music artists such as Thomas A. Dorsey, Sam Collins, Jaybird Coleman, as well as early hillbilly or country music performers such as Vernon Dalhart, Bradley Kincaid, Ernest Stoneman, Fiddlin' Doc Roberts, and Gene Autry. Blues artists from Chicago, such as Georgia Tom Dorsey, Big Bill Broonzy, and Scrapper Blackwell, recorded in Richmond.[6] The label preserved several rare varieties of traditional Kentucky music thanks to the work of talent scouts Dennis Taylor and, eventually, one of Taylor's recruits the Fiddlin' Doc Roberts, recording more Kentucky musicians than any other state.[20][14] Taylor brought hundreds of Kentucky musicians to Richmond between 1925 and 1931, including Asa Martin, Marion Underwood, and Charlie Taylor.[20]

Many early religious recordings were made by Homer Rodeheaver, early shape note singers and others.[21] Classical ensembles around the Midwest, such as the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, traveled to Richmond to record. Gennett also recorded groups such as Gonzalez's Mexican Band, the Hawaiian Guitars, the National Marimba Orchestra, and the Italian Degli Arditi Orchestra.[6]

Temporary recording studios were sometimes set up in various Starr Piano Company stores or other buildings. Their downtown Cincinnati, Ohio store recorded West Virginian singer David Miller for a time.[22] The Birmingham, Alabama store, in July and August 1927 under the direction of recording engineer Gordon Soule, which attracted many Southern country blues artists such as Jaybird Coleman and Johnny Watson under the name Daddy Stove Pipe.[23][8] The Birmingham studio also recorded William Harris, an early Mississippi Delta blues player.[11] From September to November 1927, portable sound equipment was set up in the Hotel Lowry in St. Paul, Minnesota where primarily Swedish, German, and Polish folk music was recorded.[8] Temporary studios were set up in Chicago from November-December 1927 and February-April 1928.[8]

By the late 1920s, Gennett was pressing records for more than 25 labels worldwide, including budget disks for the Sears catalog.[20] In 1926, Fred Gennett created Champion Records as a budget label for tunes previously released on Gennett.[24] Many of the recording artists used pseudonyms, such as the Seven Champions for Bailey's Lucky Seven, Skillet Dick and His Frying Pans for Syd Valentine and His Patent Leather Kids - a Black Indiana jazz trio, and the Hill Top Inn Orchestra for Guy Lombardo and His Royal Canadians. Some Champion artists were not informed that their recordings were reissued under pseudonyms.[25]

Gennett issued a few early electrically recorded masters recorded in the Autograph studios in Chicago in 1925. These recordings were exceptionally crude, and like many other Autograph issues can be easily mistaken for acoustic masters. Gennett began serious electrical recording in March 1926, using a process licensed from General Electric which was found to be unsatisfactory. Although the quality of the recordings taken by the General Electric process was quite good, there were many customer complaints about poor wear characteristics of the electric process records. The composition of the Gennett biscuit (record material) was of insufficient hardness to withstand the increased wear that resulted when the new recordings with their greatly increased frequency range were played on obsolete phonographs with mica diaphragm reproducers. The company discontinued recording by this process in August 1926, and did not return to electric recording until February 1927, after signing a new agreement to license the RCA Photophone recording process. The company also introduced an improved record biscuit which was adequate to the demands imposed by the electric recording process. The improved records were identified by a newly designed black label touting the "New Electrobeam" process.[26]

Recordings were not limited to music. In 1923, orator and statesman William Jennings Bryan traveled to Richmond to record portions of his 1896 Cross of Gold speech, which was released in 1924.[27][12] In the 1930s, Harry Gennett, Jr. became involved in the recording business and roamed the country in the Gennett recording truck producing sound effects. The Gennett catalog of sound recordsings would be sold by mail to radio stations and filmmakers.[27]

The label was hit severely by the Great Depression in 1930. It cut back on record recording and production and only maintained the budget Champion label until halting activities altogether in 1934.[28] Throughout the 1930s, Fred Wiggins sold thousands of metal discs, which would be worth millions after Gennett's rise to fame, for scrap money, likely to make payroll for Starr Piano employess.[11] At this time, the only product Gennett Records produced under its own name was a series of recorded sound effects for use by radio stations. In 1935, the Starr Piano Company sold some Gennett masters, and the Gennett and Champion trademarks to Decca Records.[8] Jack Kapp of Decca was primarily interested in jazz, blues and old time music items in the Gennett catalog which he thought would add depth to the selections offered by the newly organized Decca. Kapp attempted to revive the Gennett and Champion labels between 1935 and 1937 specializing in bargain pressings of race and old-time music with but little success.[27]

The Starr record plant soldiered on under the supervision of Harry Gennett through the remainder of the decade by offering contract pressing services. For a time the Starr Piano Company was the principal manufacturer of Decca records, but much of this business dried up after Decca purchased its own pressing plant in 1938 (the Newaygo, Michigan, plant that formerly had pressed Brunswick and Vocalion records). In the years remaining before World War II, Gennett did contract pressing for New York-based jazz and folk music labels, including Joe Davis, who briefly produced records on Gennett, Beacon, and Joe Davis labels that were pressed in Starr Valley.[29]

With the coming of the Second World War, the War Production Board in March 1942 declared shellac a rationed commodity, limiting record manufacturers to 70% of their 1939 shellac usage. Newly organized record labels were forced to purchase their shellac from existing companies.[30] Joe Davis purchased the Gennett shellac allocation, some of which he used for his own labels, and some of which he sold to the newly formed Capitol Records. Harry Gennett intended to use the funds from the sale of his shellac ration to modernize this pressing plant after Victory, but there is no indication that he did so. Gennett sold decreasing numbers of special purpose records (mostly sound effects, skating rink, and church tower chimes) until 1947 or 1948, and the business then faded away.

Brunswick Records acquired the old Gennett pressing plant for Decca. After Decca opened a new pressing plant in Pinckneyville, Illinois, in 1956, the old Gennett plant in Richmond, Indiana, was sold to Mercury Records in 1958.[31] Mercury operated the historic plant until 1969 when it moved to a nearby modern plant later operated by Cinram.[32]

Gennett Walk of Fame

[edit]In September 2007, the Starr-Gennett Foundation began to honor the most important Gennett artists on a Walk of Fame near the site of Gennett's Richmond, Indiana, recording studio.[33]

The Gennett Walk of Fame is located along South 1st Street in Richmond at the site of the Starr Piano Company and embedded in the Whitewater Gorge Trail, which connects to the longer Cardinal Greenway Trail. Both trails are part of the American Discovery Trail, the only coast-to-coast, non-motorized recreational trail.

The Foundation convened its National Advisory Board in January, 2006, to choose the first 10 inductees. The inductees are selected from: classic jazz, old-time country, blues, gospel (African-American and Southern), American popular song, ethnic, historic/spoken, and classical, giving preference to the first five categories.

The consensus selection for the first inductee in the Gennett Walk of Fame was Louis Armstrong.[33] The first ten inductees were:

- Louis Armstrong

- Bix Beiderbecke

- Jelly Roll Morton

- Hoagy Carmichael

- Gene Autry

- Vernon Dalhart

- Big Bill Broonzy

- Georgia Tom

- King Oliver

- Lawrence Welk

A second set of ten nominees was inducted in 2008:

- Homer Rodeheaver

- Fats Waller

- Duke Ellington

- Uncle Dave Macon

- Coleman Hawkins

- Charley Patton

- Sidney Bechet

- Blind Lemon Jefferson

- Fletcher Henderson

- Guy Lombardo

2009 Inductees:

- Artie Shaw

- Wendell Hall

- Bradley Kincaid

- Ernest Stoneman and Hattie Frost Stoneman

- New Orleans Rhythm Kings

2010 Inductees:

2011 Inductees:

- Roosevelt Sykes

- Bailey's Lucky Seven

2012 Inductees:

2013 Inductee:

2014 Inductee:

2016 Inductee:

References

[edit]- ^ "ABC Book". National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ a b Seubert, David. "DAHR to Include Gennett Records". Discography of American Historical Recordings. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ^ a b c Barnett, Kyle (2020). Record cultures: the transformation of the U.S. recording industry. Ann Arbor, [Michigan]: University of Michigan Press. pp. 41–6. ISBN 978-0-472-12431-2.

- ^ a b "Finding Aid for the Gennett Collection". Online Archive of California. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Rick; Gioia, Ted (2013). Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy: Gennett Records and the rise of America's musical grassroots (Revised and expanded ed.). Bloomington Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 21–24. ISBN 978-0-253-00747-6.

- ^ a b c Kennedy, Rick; Gioia, Ted (2013). Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy: Gennett Records and the rise of America's musical grassroots (Revised and expanded ed.). Bloomington Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 34–38. ISBN 978-0-253-00747-6.

- ^ Blackwood, Scott (2023). The rise and fall of Paramount Records: a great migration story, 1917-1932 (First printing ed.). Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8071-7914-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Kay, George W. (1953). "Those Fabulous Gennett's! The Life Story of a Remarkable Label". The Record Changer: 4–13.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Rick; Gioia, Ted (2013). Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy: Gennett Records and the rise of America's musical grassroots (Revised and expanded ed.). Bloomington Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 28–31. ISBN 978-0-253-00747-6.

- ^ Brothers, Thomas (2014). Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-393-06582-4.

- ^ a b c Kennedy, Rick; McNutt, Randy (1999). Little labels, big sound: small record companies and the rise of American music. Bloomington, (Ind.) Indianapolis, (Ind.): Indiana university press. pp. 2–19. ISBN 978-0-253-33548-7.

- ^ a b Painter, Alex (2020). Blackball in the Hoosier Heartland: Unearthing the Negro Leagues Baseball History of Richmond, Indiana. Morrisville, North Carolina: Lulu Publishing. pp. 100–101. ISBN 9781678166717.

- ^ Tom Lord's The Jazz Discography says Hines' first recording was here with Deppe on 13 October 1923

- ^ a b c Dahan, Charlie B. (May 3, 2016). "The Music Never Stopped: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of Gennett Records". Retrieved Feb 11, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Egan, Timothy (2023). A fever in the heartland: the Ku Klux Klan's plot to take over America, and the woman who stopped them. New York, NY: Viking. pp. 67–72. ISBN 978-0-7352-2526-8.

- ^ a b Sutton, Allan (2016). Race Records and the American Recording Industry, 1919-1945: An Illustrated History. pp. 101–5, 110. ISBN 9780997333305.

- ^ a b Moore, Leonard J. (2005). Citizen klansmen: the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921 - 1928 (3. [print] ed.). Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1981-4.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy, Rick; Gioia, Ted (2013). Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy: Gennett Records and the rise of America's musical grassroots. Bloomington Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 38–41. ISBN 978-0-253-00747-6.

- ^ Dahan, Charlie (2014-05-28). "May 28th in Gennett History, 1924: The 100% American Orchestra Recorded "Daddy Swiped Our Last Clean Sheet And Joined The KKK"". Gennett Records Discography. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ^ a b c Wolfe, Charles K. (1982). Kentucky country: folk and country music of Kentucky (1st ed.). Lexington, Ky: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 26–9. ISBN 978-0-8131-0879-7.

- ^ Mungons, Kevin and Douglas Yeo (2021). Homer Rodeheaver and the Rise of the Gospel Music Industry. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. pp. 118, 176–77. ISBN 978-0-252-08583-3.

- ^ Kennedy, Rick; Gioia, Ted (2013). Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy: Gennett Records and the rise of America's musical grassroots. Bloomington Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-253-00747-6.

- ^ Kennedy, Rick; Gioia, Ted (2013). Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy: Gennett Records and the rise of America's musical grassroots. Bloomington Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 207–9.

- ^ Kennedy, Rick (1994). Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy: Gennett Studios and the Birth of Recorded Jazz. Indiana University Press. p. 141.

- ^ Kennedy, Rick; Gioia, Ted (2013). Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy: Gennett Records and the rise of America's musical grassroots. Bloomington Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 168–9. ISBN 978-0-253-00747-6.

- ^ Kennedy, Rick; Gioia, Ted (2013). Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy: Gennett Records and the rise of America's musical grassroots. Bloomington Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 172–4. ISBN 978-0-253-00747-6.

- ^ a b c Kennedy, Rick; Gioia, Ted (2013). Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy: Gennett Records and the rise of America's musical grassroots. Bloomington Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 237–8. ISBN 978-0-253-00747-6.

- ^ "Starr-Gennett Foundation". Starr-Gennett Foundation. Retrieved 2024-02-12.

- ^ Kennedy, Rick; Gioia, Ted (2013). Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy: Gennett Records and the rise of America's musical grassroots. Bloomington Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-253-00747-6.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (13 February 1971). "Patti Helps Re-Create War Years". The Portsmouth Times. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ^ "Billboard". google.com. 5 May 1958. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "After the Starr Piano Company". StarrGennett.org. p. 6. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008.

- ^ a b "Starr-Gennett Foundation". Starr-Gennett Foundation. Retrieved 2024-02-12.

External links

[edit]- The Starr-Gennett Foundation

- 2012 PBS History Detectives episode "Fiery Cross" regarding Klan records recorded at Gennett

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. IN-42, "Starr Piano Factory & Richmond Gas Company, G Street Bridge & Main Street Bridge, Richmond, Wayne County, IN", 6 photos, 6 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- Gennett Records on the Internet Archive's Great 78 Project

- Gennett Records discography at Discogs as 'Gennett'

- Gennett Records discography at Discogs as 'Gennett Records'

- Gennett Records artists

- American record labels

- Vertical cut record labels

- Record labels established in 1917

- Record labels disestablished in 1948

- Re-established companies

- Jazz record labels

- Walks of fame

- Music halls of fame

- Richmond, Indiana

- Defunct companies based in Indiana

- 1917 establishments in Indiana

- 1948 disestablishments in Indiana