Теория привязанности

— Теория привязанности это психологическая и эволюционная теория, касающаяся отношений между людьми . Самый важный принцип заключается в том, что для выживания маленьких детей и развития здорового социального и эмоционального функционирования им необходимо развивать отношения, по крайней мере, с одним основным опекуном. Теорию сформулировал психиатр и психоаналитик Джон Боулби (1907–90). [1] [2]

В рамках теории привязанности поведение младенца , связанное с привязанностью, — это, прежде всего, поиск близости к объекту привязанности в стрессовых ситуациях. [2] [3] Младенцы привязываются к взрослым, которые чувствительны и отзывчивы в социальном взаимодействии с ними и продолжают постоянно заботиться о них в течение нескольких месяцев, в возрасте от шести месяцев до двух лет. Во второй части дети начинают использовать фигурки-приспособления как надежную основу для исследования и возвращения. Реакция родителей приводит к развитию моделей привязанности. Это, в свою очередь, приводит к внутренним рабочим моделям, которые будут определять чувства, мысли и ожидания человека в последующих отношениях. [4] Сепарационная тревога или горе после потери объекта привязанности считается нормальной и адаптивной реакцией привязанного младенца. Возможно, такое поведение развилось потому, что оно увеличивает вероятность выживания. [5]

Исследования психолога развития Мэри Эйнсворт в 1960-х и 70-х годах легли в основу основных концепций и тем, касающихся материнской отзывчивости и чувствительности к детскому стрессу. [6] Она ввела концепцию «надежной основы» и разработала теорию моделей привязанности у младенцев: надежная привязанность, избегающая привязанность и тревожная привязанность. [7] Четвертый паттерн — дезорганизованная привязанность — был выявлен позже. В 1980-х годах теория была распространена на привязанность у взрослых . [8] Другие взаимодействия можно рассматривать как включающие компоненты поведения привязанности. К ним относятся отношения со сверстниками в любом возрасте, романтическое и сексуальное влечение, а также реагирование на потребности в уходе за младенцами, больными и пожилыми людьми.

Чтобы сформулировать всеобъемлющую теорию ранних привязанностей, Боулби исследовал ряд областей, включая эволюционную биологию , теорию объектных отношений , теорию систем управления , а также области этологии и когнитивной психологии . [9] После предварительных статей, начиная с 1958 года, Боулби опубликовал полную теорию в трилогии «Привязанность и потеря» (1969–82). На заре существования теории академические психологи критиковали Боулби, а психоаналитическое сообщество подвергало его остракизму за отклонение от психоаналитических доктрин. [10] Однако теория привязанности стала доминирующим подходом к пониманию раннего социального развития и вызвала волну эмпирических исследований формирования близких отношений детей. [11] Критика теории привязанности касается темперамента, сложности социальных отношений и ограничений дискретных моделей классификаций. Теория привязанности была существенно модифицирована в результате эмпирических исследований, но концепции стали общепринятыми. [10] Теория привязанности легла в основу новых методов лечения и послужила основой для существующих, а ее концепции использовались при формулировании социальной политики и политики ухода за детьми для поддержки ранних отношений привязанности. [12]

Вложение

[ редактировать ]

В рамках теории привязанности привязанность означает нежную связь или связь между человеком и объектом привязанности (обычно опекуном/опекуном). Такие связи могут быть взаимными между двумя взрослыми, но между ребенком и лицом, осуществляющим уход, эти связи основаны на потребности ребенка в безопасности, защищенности и защите, что наиболее важно в младенчестве и детстве. [13] Теория привязанности не является исчерпывающим описанием человеческих отношений и не является синонимом любви и привязанности, хотя они могут указывать на существование связей. В отношениях между ребенком и взрослым связь ребенка называется «привязанностью», а взаимный эквивалент опекуна называется «узами заботы». [14] Теория предполагает, что дети инстинктивно привязываются к тем, кто за ними ухаживает. [15] с целью выживания и, в конечном итоге, генетической репликации. [14] Биологическая цель – выживание, а психологическая – безопасность. [11] Отношения ребенка со своим объектом привязанности особенно важны в угрожающих ситуациях. Доступ к безопасной фигуре уменьшает страх детей, когда они сталкиваются с угрожающими ситуациями. Снижение уровня страха не только важно для общей психической устойчивости, но также влияет на то, как дети могут реагировать на угрожающие ситуации. Наличие поддерживающей фигуры особенно важно в годы развития ребенка. [16] Помимо поддержки, решающее значение в отношениях между опекуном и ребенком имеет настройка (точное понимание и эмоциональная связь). Если опекун плохо настроен на ребенка, ребенок может начать чувствовать себя непонятым и тревожным. [17]

Младенцы будут привязываться к любому постоянному лицу, осуществляющему уход, которое будет чутким и отзывчивым в социальном взаимодействии с ними. Качество социального взаимодействия более влиятельно, чем количество потраченного времени. Биологическая мать обычно является основной фигурой привязанности, но ее роль может взять на себя любой, кто последовательно ведет себя «материнским» образом в течение определенного периода времени. В рамках теории привязанности это означает набор моделей поведения, которые включают активное социальное взаимодействие с младенцем и готовность реагировать на сигналы и подходы. [18] Ничто в теории не предполагает, что отцы с одинаковой вероятностью станут основными фигурами привязанности, если они обеспечивают большую часть ухода за ребенком и связанного с ним социального взаимодействия. [19] [20] Надежная привязанность к отцу, который является «вторичной фигурой привязанности», также может противодействовать возможным негативным последствиям неудовлетворительной привязанности к матери, которая является первичной фигурой привязанности. [21]

Некоторые младенцы направляют поведение привязанности (поиск близости) к более чем одному объекту привязанности почти сразу же, как только они начинают проявлять дискриминацию между лицами, осуществляющими уход; большинство из них делают это на втором году обучения. Эти фигуры расположены иерархически, причем основная фигура прикрепления находится наверху. [22] Установленная цель поведенческой системы привязанности — поддерживать связь с доступным и доступным объектом привязанности. [23] «Тревога» — термин, обозначающий активацию поведенческой системы привязанности, вызванную страхом опасности. «Тревога» — это ожидание или страх быть отрезанным от объекта привязанности. Если фигура недоступна или не отвечает, возникает дистресс разлуки. [24] У младенцев физическое разлучение может вызвать тревогу и гнев, за которыми следуют печаль и отчаяние. К трем или четырем годам физическое разделение уже не представляет такой угрозы для связи ребенка с объектом привязанности. Угрозы безопасности у детей старшего возраста и взрослых возникают в результате длительного отсутствия, нарушений общения, эмоциональной недоступности или признаков отвержения или покинутости. [23]

Поведение

[ редактировать ]

Поведенческая система привязанности служит для достижения или поддержания близости к объекту привязанности. [5]

Поведение, предшествующее привязанности, возникает в первые шесть месяцев жизни. На первом этапе (первые два месяца) младенцы улыбаются, лепечут и плачут, чтобы привлечь внимание потенциальных воспитателей. Хотя младенцы этого возраста учатся различать тех, кто за ними ухаживает, такое поведение направлено на всех, кто находится поблизости.

Во время второй фазы (от двух до шести месяцев) младенец различает знакомых и незнакомых взрослых, становясь более отзывчивым по отношению к лицу, осуществляющему уход; К диапазону поведения добавляются следование и цепляние. Поведение младенца по отношению к лицу, осуществляющему уход, организуется на целенаправленной основе для достижения условий, позволяющих ему чувствовать себя в безопасности. [25]

К концу первого года жизни младенец способен демонстрировать различные виды привязанности, направленные на поддержание близости. Они проявляются в протесте против ухода опекуна, приветствии его возвращения, цеплянии, когда он напуган, и следовании, когда это возможно. [26]

С развитием передвижения младенец начинает использовать опекуна или опекунов как «безопасную базу», с которой можно исследовать. [25] [27] : 71 Исследование младенца происходит лучше, когда присутствует опекун, потому что система привязанности ребенка расслаблена и он может свободно исследовать. Если опекун недоступен или не отвечает, поведение привязанности проявляется сильнее. [28] Тревога, страх, болезнь и усталость заставят ребенка усилить привязанность. [29]

После второго года, когда ребенок начинает видеть в воспитателе самостоятельную личность, формируется более сложное и целенаправленное партнерство. [30] Дети начинают замечать цели и чувства других и соответственно планировать свои действия.

Принципы

[ редактировать ]Современная теория привязанности основана на трёх принципах: [31]

- Связь – это внутренняя потребность человека.

- Регулирование эмоций и страха для повышения жизненных сил.

- Содействие адаптивности и росту.

Обычное поведение и эмоции привязанности, проявляющиеся у большинства социальных приматов, включая человека, являются адаптивными . Долгосрочная эволюция этих видов включала отбор социального поведения, которое повышает вероятность индивидуального или группового выживания. Обычно наблюдаемое поведение привязанности малышей, остающихся рядом со знакомыми людьми, имело бы преимущества в плане безопасности в условиях ранней адаптации и имеет аналогичные преимущества сегодня. Боулби считал среду ранней адаптации похожей на нынешние общества охотников-собирателей . [32] Преимущество выживания заключается в способности чувствовать потенциально опасные условия, такие как незнакомство, одиночество или быстрое приближение. По мнению Боулби, стремление к близости к объекту привязанности перед лицом угрозы является «установленной целью» поведенческой системы привязанности. [33]

Первоначальное описание Боулби периода чувствительности , в течение которого может формироваться привязанность, продолжающегося от шести месяцев до двух-трех лет, было изменено более поздними исследователями. Эти исследователи показали, что действительно существует чувствительный период, в течение которого, если возможно, формируются привязанности, но временные рамки шире, а эффект менее фиксированный и необратимый, чем предполагалось вначале. [34]

В ходе дальнейших исследований авторы, обсуждающие теорию привязанности, пришли к выводу, что на социальное развитие влияют как более поздние, так и более ранние отношения. Ранние шаги по установлению привязанности происходят легче всего, если за ребенком ухаживает один человек или время от времени о нем заботится небольшое количество других людей. По мнению Боулби, почти с самого начала у многих детей есть более одного человека, к которому они направляют поведение привязанности. К этим цифрам относятся по-разному; у ребенка существует сильная склонность направлять поведение привязанности главным образом на одного конкретного человека. Боулби использовал термин «монотропия», чтобы описать эту предвзятость. [35] Исследователи и теоретики отказались от этой концепции, поскольку она может означать, что отношения со специальной фигурой качественно отличаются от отношений с другими фигурами. Скорее, современное мышление постулирует определенную иерархию отношений. [10] [36]

Ранний опыт общения с лицами, осуществляющими уход, постепенно порождает систему мыслей, воспоминаний, убеждений, ожиданий, эмоций и поведения в отношении себя и других. Эта система, получившая название «внутренняя рабочая модель социальных отношений», продолжает развиваться со временем и опытом. [37]

Внутренние модели регулируют, интерпретируют и прогнозируют связанное с привязанностью поведение личности и объекта привязанности. По мере того, как они развиваются в соответствии с изменениями окружающей среды и развития, они включают в себя способность размышлять и сообщать о прошлых и будущих отношениях привязанности. [4] Они позволяют ребенку справляться с новыми типами социальных взаимодействий; зная, например, что к младенцу следует относиться иначе, чем к ребенку старшего возраста, или что взаимодействие с учителями и родителями имеет общие характеристики. Даже взаимодействие с тренерами имеет схожие характеристики, поскольку спортсмены, установившие отношения привязанности не только со своими родителями, но и с тренерами, будут играть роль в развитии спортсменов в их будущем виде спорта. [38] Эта внутренняя рабочая модель продолжает развиваться на протяжении всей взрослой жизни, помогая справляться с дружбой, браком и родительством, каждый из которых предполагает различное поведение и чувства. [39] [37]

Развитие привязанности — это транзакционный процесс. Специфическое поведение привязанности начинается с предсказуемого, по-видимому, врожденного поведения в младенчестве. [40] Они меняются с возрастом, частично определяемые опытом, частично ситуативными факторами. [41] Поскольку поведение привязанности меняется с возрастом, оно зависит от взаимоотношений. Поведение ребенка при воссоединении с опекуном определяется не только тем, как тот обращался с ребенком раньше, но и историей воздействия ребенка на опекуна. [42] [43]

Культурные различия

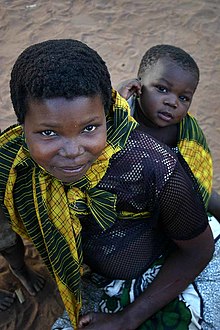

[ редактировать ]В западной культуре воспитания детей основное внимание уделяется единственной привязанности, прежде всего к матери. Эта диадная модель — не единственная стратегия привязанности, позволяющая вырастить безопасного и эмоционально подготовленного ребенка. Наличие одного, надежно отзывчивого и чуткого опекуна (а именно матери) не гарантирует окончательного успеха ребенка. Результаты исследований в Израиле, Голландии и Восточной Африке показывают, что дети, у которых есть несколько воспитателей, не только растут, чувствуя себя в безопасности, но и развивают «более развитые способности смотреть на мир с разных точек зрения». [44] Эти доказательства легче найти в общинах охотников-собирателей, подобных тем, которые существуют в сельской Танзании. [45]

In hunter-gatherer communities, in the past and present, mothers are the primary caregivers, but share the maternal responsibility of ensuring the child's survival with a variety of different allomothers. So while the mother is important, she is not the only opportunity for relational attachment a child can make. Several group members (with or without blood relation) contribute to the task of bringing up a child, sharing the parenting role and therefore can be sources of multiple attachment. There is evidence of this communal parenting throughout history that "would have significant implications for the evolution of multiple attachment."[46]

In "non-metropolis" India (where "dual income nuclear families" are more the norm and dyadic mother relationship is)[clarify], where a family normally consists of 3 generations (and sometimes 4: great-grandparents, grandparents, parents, and child or children), the child or children would have four to six caregivers from whom to select their "attachment figure". A child's "uncles and aunts" (parents' siblings and their spouses) also contribute to the child's psycho-social enrichment.[47]

Although it has been debated for years, and there are differences across cultures, research has shown that the three basic aspects of attachment theory are, to some degree, universal.[48] Studies in Israel and Japan resulted in findings which diverge from a number of studies completed in Western Europe and the United States. The prevailing hypotheses are: 1) that secure attachment is the most desirable state, and the most prevalent; 2) maternal sensitivity influences infant attachment patterns; and 3) specific infant attachments predict later social and cognitive competence.[48]

Attachment patterns

[edit]The strength of a child's attachment behaviour in a given circumstance does not indicate the 'strength' of the attachment bond. Some insecure children will routinely display very pronounced attachment behaviours, while many secure children find that there is no great need to engage in either intense or frequent shows of attachment behaviour."[49]

Individuals with different attachment styles have different beliefs about romantic love period, availability, trust capability of love partners and love readiness.[50]

Secure attachment

[edit]A toddler who is securely attached to his or her parent (or other familiar caregiver) will explore freely while the caregiver is present, typically engages with strangers, is often visibly upset when the caregiver departs, and is generally happy to see the caregiver return. The extent of exploration and of distress are affected, however, by the child's temperamental make-up and by situational factors as well as by attachment status. A child's attachment is largely influenced by their primary caregiver's sensitivity to their needs. Parents who consistently (or almost always) respond to their child's needs will create securely attached children. Such children are certain that their parents will be responsive to their needs and communications.[51]

In the traditional Ainsworth et al. (1978) coding of the Strange Situation, secure infants are denoted as "Group B" infants and they are further subclassified as B1, B2, B3, and B4.[52] Although these subgroupings refer to different stylistic responses to the comings and goings of the caregiver, they were not given specific labels by Ainsworth and colleagues, although their descriptive behaviours led others (including students of Ainsworth) to devise a relatively "loose" terminology for these subgroups. B1's have been referred to as "secure-reserved", B2's as "secure-inhibited", B3's as "secure-balanced", and B4's as "secure-reactive". However, in academic publications the classification of infants (if subgroups are denoted) is typically simply "B1" or "B2", although more theoretical and review-oriented papers surrounding attachment theory may use the above terminology. Secure attachment is the most common type of attachment relationship seen throughout societies.[53]

Securely attached children are best able to explore when they have the knowledge of a secure base (their caregiver) to return to in times of need. When assistance is given, this bolsters the sense of security and also, assuming the parent's assistance is helpful, educates the child on how to cope with the same problem in the future. Therefore, secure attachment can be seen as the most adaptive attachment style. According to some psychological researchers, a child becomes securely attached when the parent is available and able to meet the needs of the child in a responsive and appropriate manner. At infancy and early childhood, if parents are caring and attentive towards their children, those children will be more prone to secure attachment.[54]

Anxious-ambivalent attachment

[edit]Anxious-ambivalent attachment is a form of insecure attachment and is also misnamed as "resistant attachment".[53][55] In general, a child with an anxious-ambivalent pattern of attachment will typically explore little (in the Strange Situation) and is often wary of strangers, even when the parent is present. When the caregiver departs, the child is often highly distressed showing behaviours such as crying or screaming. The child is generally ambivalent when the caregiver returns.[52] The anxious-ambivalent strategy is a response to unpredictably responsive caregiving, and the displays of anger (ambivalent resistant, C1) or helplessness (ambivalent passive, C2) towards the caregiver on reunion can be regarded as a conditional strategy for maintaining the availability of the caregiver by preemptively taking control of the interaction.[56][57]

The C1 (ambivalent resistant) subtype is coded when "resistant behavior is particularly conspicuous. The mixture of seeking and yet resisting contact and interaction has an unmistakably angry quality and indeed an angry tone may characterize behavior in the preseparation episodes".[52]

Regarding the C2 (ambivalent passive) subtype, Ainsworth et al. wrote:

Perhaps the most conspicuous characteristic of C2 infants is their passivity. Their exploratory behavior is limited throughout the SS and their interactive behaviors are relatively lacking in active initiation. Nevertheless, in the reunion episodes they obviously want proximity to and contact with their mothers, even though they tend to use signalling rather than active approach, and protest against being put down rather than actively resisting release ... In general the C2 baby is not as conspicuously angry as the C1 baby.[52]

Research done by McCarthy and Taylor (1999) found that children with abusive childhood experiences were more likely to develop ambivalent attachments. The study also found that children with ambivalent attachments were more likely to experience difficulties in maintaining intimate relationships as adults.[58]

Anxious-avoidant and dismissive-avoidant attachment

[edit]An infant with an anxious-avoidant pattern of attachment will avoid or ignore the caregiver—showing little emotion when the caregiver departs or returns. The infant will not explore very much regardless of who is there. Infants classified as anxious-avoidant (A) represented a puzzle in the early 1970s. They did not exhibit distress on separation, and either ignored the caregiver on their return (A1 subtype) or showed some tendency to approach together with some tendency to ignore or turn away from the caregiver (A2 subtype). Ainsworth and Bell theorized that the apparently unruffled behaviour of the avoidant infants was in fact a mask for distress, a hypothesis later evidenced through studies of the heart-rate of avoidant infants.[59][60]

Infants are depicted as anxious-avoidant when there is:

... conspicuous avoidance of the mother in the reunion episodes which is likely to consist of ignoring her altogether, although there may be some pointed looking away, turning away, or moving away ... If there is a greeting when the mother enters, it tends to be a mere look or a smile ... Either the baby does not approach his mother upon reunion, or they approach in "abortive" fashions with the baby going past the mother, or it tends to only occur after much coaxing ... If picked up, the baby shows little or no contact-maintaining behavior; he tends not to cuddle in; he looks away and he may squirm to get down.[52]

Ainsworth's narrative records showed that infants avoided the caregiver in the stressful Strange Situation Procedure when they had a history of experiencing rebuff of attachment behaviour. The infant's needs were frequently not met and the infant had come to believe that communication of emotional needs had no influence on the caregiver.

Ainsworth's student Mary Main theorized that avoidant behaviour in the Strange Situation Procedure should be regarded as "a conditional strategy, which paradoxically permits whatever proximity is possible under conditions of maternal rejection" by de-emphasising attachment needs.[61]

Main proposed that avoidance has two functions for an infant whose caregiver is consistently unresponsive to their needs. Firstly, avoidant behaviour allows the infant to maintain a conditional proximity with the caregiver: close enough to maintain protection, but distant enough to avoid rebuff. Secondly, the cognitive processes organising avoidant behaviour could help direct attention away from the unfulfilled desire for closeness with the caregiver—avoiding a situation in which the child is overwhelmed with emotion ("disorganized distress"), and therefore unable to maintain control of themselves and achieve even conditional proximity.[62]

Disorganized/disoriented attachment

[edit]Beginning in 1983, Crittenden offered A/C and other new organized classifications (see below). Drawing on records of behaviours discrepant with the A, B and C classifications, a fourth classification was added by Ainsworth's colleague Mary Main.[63] In the Strange Situation, the attachment system is expected to be activated by the departure and return of the caregiver. If the behaviour of the infant does not appear to the observer to be coordinated in a smooth way across episodes to achieve either proximity or some relative proximity with the caregiver, then it is considered 'disorganized' as it indicates a disruption or flooding of the attachment system (e.g. by fear). Infant behaviours in the Strange Situation Protocol coded as disorganized/disoriented include overt displays of fear; contradictory behaviours or affects occurring simultaneously or sequentially; stereotypic, asymmetric, misdirected or jerky movements; or freezing and apparent dissociation. Lyons-Ruth has urged, however, that it should be more widely "recognized that 52% of disorganized infants continue to approach the caregiver, seek comfort, and cease their distress without clear ambivalent or avoidant behavior".[64]

The benefit of this category was hinted at earlier in Ainsworth's own experience finding difficulties in fitting all infant behaviour into the three classifications used in her Baltimore study. Ainsworth and colleagues sometimes observed

tense movements such as hunching the shoulders, putting the hands behind the neck and tensely cocking the head, and so on. It was our clear impression that such tension movements signified stress, both because they tended to occur chiefly in the separation episodes and because they tended to be prodromal to crying. Indeed, our hypothesis is that they occur when a child is attempting to control crying, for they tend to vanish if and when crying breaks through.[65]

Such observations also appeared in the doctoral theses of Ainsworth's students. Crittenden, for example, noted that one abused infant in her doctoral sample was classed as secure (B) by her undergraduate coders because her strange situation behaviour was "without either avoidance or ambivalence, she did show stress-related stereotypic headcocking throughout the strange situation. This pervasive behavior, however, was the only clue to the extent of her stress".[66]

There is rapidly growing interest in disorganized attachment from clinicians and policy-makers as well as researchers.[67] However, the disorganized/disoriented attachment (D) classification has been criticized by some for being too encompassing, including Ainsworth herself.[68] In 1990, Ainsworth put in print her blessing for the new 'D' classification, though she urged that the addition be regarded as "open-ended, in the sense that subcategories may be distinguished", as she worried that too many different forms of behaviour might be treated as if they were the same thing.[69] Indeed, the D classification puts together infants who use a somewhat disrupted secure (B) strategy with those who seem hopeless and show little attachment behaviour; it also puts together infants who run to hide when they see their caregiver in the same classification as those who show an avoidant (A) strategy on the first reunion and then an ambivalent-resistant (C) strategy on the second reunion. Perhaps responding to such concerns, George and Solomon have divided among indices of disorganized/disoriented attachment (D) in the Strange Situation, treating some of the behaviours as a 'strategy of desperation' and others as evidence that the attachment system has been flooded (e.g. by fear, or anger).[70]

Crittenden also argues that some behaviour classified as Disorganized/disoriented can be regarded as more 'emergency' versions of the avoidant and/or ambivalent/resistant strategies, and function to maintain the protective availability of the caregiver to some degree. Sroufe et al. have agreed that "even disorganized attachment behaviour (simultaneous approach-avoidance; freezing, etc.) enables a degree of proximity in the face of a frightening or unfathomable parent".[71] However, "the presumption that many indices of 'disorganization' are aspects of organized patterns does not preclude acceptance of the notion of disorganization, especially in cases where the complexity and dangerousness of the threat are beyond children's capacity for response."[72] For example, "Children placed in care, especially more than once, often have intrusions. In videos of the Strange Situation Procedure, they tend to occur when a rejected/neglected child approaches the stranger in an intrusion of desire for comfort, then loses muscular control and falls to the floor, overwhelmed by the intruding fear of the unknown, potentially dangerous, strange person."[73]

Main and Hesse[74] found most of the mothers of these children had suffered major losses or other trauma shortly before or after the birth of the infant and had reacted by becoming severely depressed.[75] In fact, fifty-six per cent of mothers who had lost a parent by death before they completed high school had children with disorganized attachments.[74] Subsequent studies, whilst emphasising the potential importance of unresolved loss, have qualified these findings.[76] For example, Solomon and George found unresolved loss in the mother tended to be associated with disorganized attachment in their infant primarily when they had also experienced an unresolved trauma in their life prior to the loss.[77]

Categorization differences across cultures

[edit]Across different cultures deviations from the Strange Situation Protocol have been observed. A Japanese study in 1986 (Takahashi) studied 60 Japanese mother-infant pairs and compared them with Ainsworth's distributional pattern. Although the ranges for securely attached and insecurely attached had no significant differences in proportions, the Japanese insecure group consisted of only resistant children, with no children categorized as avoidant. This may be because the Japanese child rearing philosophy stressed close mother infant bonds more so than in Western cultures. In Northern Germany, Grossmann et al. (Grossmann, Huber, & Wartner, 1981; Grossmann, Spangler, Suess, & Unzner, 1985) replicated the Ainsworth Strange Situation with 46 mother infant pairs and found a different distribution of attachment classifications with a high number of avoidant infants: 52% avoidant, 34% secure, and 13% resistant (Grossmann et al., 1985). Another study in Israel found there was a high frequency of an ambivalent pattern, which according to Grossman et al. (1985) could be attributed to a greater parental push toward children's independence.

Later patterns and the dynamic-maturational model

[edit]Techniques have been developed to guide a child to verbalize their state of mind with respect to attachment. One such is the "stem story", in which a child receives the beginning of a story that raises attachment issues and is asked to complete it. This is modified for older children, adolescents and adults, where semi-structured interviews are used instead, and the way content is delivered may be as significant as the content itself.[11] However, there are no substantially validated measures of attachment for middle childhood or early adolescence (from 7 to 13 years of age).[78]

Some studies of older children have identified further attachment classifications. Main and Cassidy observed that disorganized behaviour in infancy can develop into a child using caregiver-controlling or punitive behaviour to manage a helpless or dangerously unpredictable caregiver. In these cases, the child's behaviour is organized, but the behaviour is treated by researchers as a form of disorganization, since the hierarchy in the family no longer follows parenting authority in that scenario.[79]

American psychologist Patricia McKinsey Crittenden has elaborated classifications of further forms of avoidant and ambivalent attachment behaviour, as seen in her dynamic-maturational model of attachment and adaptation (DMM). These include the caregiving and punitive behaviours also identified by Main and Cassidy (termed A3 and C3, respectively), but also other patterns such as compulsive compliance with the wishes of a threatening parent (A4).[80]

Crittenden's ideas developed from Bowlby's proposal: "Given certain adverse circumstances during childhood, the selective exclusion of information of certain sorts may be adaptive. Yet, when during adolescence and adulthood the situation changes, the persistent exclusion of the same forms of information may become maladaptive".[81]

Crittenden theorizes the human experience of danger comprise two basic components:[82]

- Emotions provoked by the potential for danger, which Crittenden refers to as "affective information." In childhood, the unexplained absence of an attachment figure would cause these emotions. A strategy an infant faced with insensitive or rejecting parenting may use to maintain availability of the attachment figure is to repress emotional information that could result in rejection by said attachment figure.[83]

- Causal or other sequentially ordered knowledge about the potential for safety or danger, which would include awareness of behaviours that indicate whether an attachment figure is available as a secure haven. If the infant represses knowledge that the caregiver is not a reliable source of protection and safety, they may use clingy and/or aggressive behaviour to demand attention and potentially increase the availability of an attachment figure who otherwise displays inconsistent or misleading responses to the infant's attachment behaviours.[84]

Crittenden proposes both kinds of information can be split off from consciousness or behavioural expression as a 'strategy' to maintain the availability of an attachment figure (see disorganized/disorriented attachment for type distinctions). Type A strategies split off emotional information about feeling threatened, and Type C strategies split off temporally-sequenced knowledge about how and why the attachment figure is available.[85] In contrast, Type B strategies use both kinds of information without much distortion.[86] For example, a toddler may have come to depend upon a Type C strategy of tantrums to maintain an unreliable attachment figure's availability, which may cause the attachment figure to respond appropriately to the child's attachment behaviours. As a result of learning the attachment figure is becoming more reliable, the toddler's reliance on coercive behaviours is reduced, and a more secure attachment may develop.[87]

Significance of patterns

[edit]Research based on data from longitudinal studies, such as the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care and the Minnesota Study of Risk and Adaption from Birth to Adulthood, and from cross-sectional studies, consistently shows associations between early attachment classifications and peer relationships as to both quantity and quality. Lyons-Ruth, for example, found that "for each additional withdrawing behavior displayed by mothers in relation to their infant's attachment cues in the Strange Situation Procedure, the likelihood of clinical referral by service providers was increased by 50%."[88]

There is an extensive body of research demonstrating a significant association between attachment organizations and children's functioning across multiple domains.[89] Early insecure attachment does not necessarily predict difficulties, but it is a liability for the child, particularly if similar parental behaviours continue throughout childhood.[90] Compared to that of securely attached children, the adjustment of insecure children in many spheres of life is not as soundly based, putting their future relationships in jeopardy. Although the link is not fully established by research and there are other influences besides attachment, secure infants are more likely to become socially competent than their insecure peers. Relationships formed with peers influence the acquisition of social skills, intellectual development and the formation of social identity. Classification of children's peer status (popular, neglected or rejected) has been found to predict subsequent adjustment.[11] Insecure children, particularly avoidant children, are especially vulnerable to family risk. Their social and behavioural problems increase or decline with deterioration or improvement in parenting. However, an early secure attachment appears to have a lasting protective function.[91] As with attachment to parental figures, subsequent experiences may alter the course of development.[11]

Studies have suggested that infants with a high-risk for autism spectrum disorders (ASD) may express attachment security differently from infants with a low-risk for ASD.[92] Behavioural problems and social competence in insecure children increase or decline with deterioration or improvement in quality of parenting and the degree of risk in the family environment.[91]

Some authors have questioned the idea that a taxonomy of categories representing a qualitative difference in attachment relationships can be developed. Examination of data from 1,139 15-month-olds showed that variation in attachment patterns was continuous rather than grouped.[93] This criticism introduces important questions for attachment typologies and the mechanisms behind apparent types. However, it has relatively little relevance for attachment theory itself, which "neither requires nor predicts discrete patterns of attachment."[94]

There is some evidence that gender differences in attachment patterns of adaptive significance begin to emerge in middle childhood. There has been a common tendency observed by researchers that males demonstrate a greater tendency to engage in criminal behavior which is suspected to be related to males being more likely to experience inadequate early attachments to primary caregivers.[95] Insecure attachment and early psychosocial stress indicate the presence of environmental risk (for example poverty, mental illness, instability, minority status, violence). Environmental risk can cause insecure attachment, while also favouring the development of strategies for earlier reproduction. Different reproductive strategies have different adaptive values for males and females: Insecure males tend to adopt avoidant strategies, whereas insecure females tend to adopt anxious/ambivalent strategies, unless they are in a very high risk environment. Adrenarche is proposed as the endocrine mechanism underlying the reorganization of insecure attachment in middle childhood.[96]

Changes in attachment during childhood and adolescence

[edit]Childhood and adolescence allows the development of an internal working model useful for forming attachments. This internal working model is related to the individual's state of mind which develops with respect to attachment generally and explores how attachment functions in relationship dynamics based on childhood and adolescent experience. The organization of an internal working model is generally seen as leading to more stable attachments in those who develop such a model, rather than those who rely more on the individual's state of mind alone in forming new attachments.[97]

Age, cognitive growth, and continued social experience advance the development and complexity of the internal working model. Attachment-related behaviours lose some characteristics typical of the infant-toddler period and take on age-related tendencies. The preschool period involves the use of negotiation and bargaining.[98] For example, four-year-olds are not distressed by separation if they and their caregiver have already negotiated a shared plan for the separation and reunion.[99]

Ideally, these social skills become incorporated into the internal working model to be used with other children and later with adult peers. As children move into the school years at about six years old, most develop a goal-corrected partnership with parents, in which each partner is willing to compromise in order to maintain a gratifying relationship.[98] By middle childhood, the goal of the attachment behavioural system has changed from proximity to the attachment figure to availability. Generally, a child is content with longer separations, provided contact—or the possibility of physically reuniting, if needed—is available. Attachment behaviours such as clinging and following decline and self-reliance increases. By middle childhood (ages 7–11), there may be a shift toward mutual coregulation of secure-base contact in which caregiver and child negotiate methods of maintaining communication and supervision as the child moves toward a greater degree of independence.[98]

The attachment system used by adolescents is seen as a "safety regulating system" whose main function is to promote physical and psychological safety. There are 2 different events that can trigger the attachment system. Those triggers include, the presence of a potential danger or stress, internal and external, and a threat of accessibility and/or availability of an attachment figure. The ultimate goal of the attachment system is security, so during a time of danger or inaccessibility the behavioural system accepts felt security in the context of the availability of protection. By adolescence we are able to find security through a variety of things, such as food, exercise, and social media.[100] Felt security can be achieved through a number of ways, and often without the physical presence of the attachment figure. Higher levels of maturity allows adolescent teens to more capably interact with their environment on their own because the environment is perceived as less threatening. Adolescents teens will also see an increase in cognitive, emotional and behavioural maturity that dictates whether or not teens are less likely to experience conditions that activate their need for an attachment figure. For example, when teenagers get sick and stay home from school, surely they want their parents to be home so they can take care of them, but they are also able to stay home by themselves without experiencing serious amounts of distress.[101] Additionally, the social environment that a school fosters impacts adolescents attachment behavior, even if these same adolescents have not had issues with attachment behavior previously. High schools that have a permissive environment compared to an authoritative environment promote positive attachment behavior. For example, when students feel connected to their teachers and peers because of their permissive schooling environment, they are less likely to skip school. Positive-attachment behavior in high schools have important implications on how a school's environment should be structured.[102]

Here are the attachment style differences during adolescence:[103]

- Secure adolescents are expected to hold their mothers at a higher rate than all other support figures, including father, significant others, and best friends.

- Insecure adolescents identify more strongly with their peers than their parents as their primary attachment figures. Their friends are seen as a significantly strong source of attachment support.

- Dismissing adolescents rate their parents as a less significant source of attachment support and would consider themselves as their primary attachment figure.

- Preoccupied adolescents would rate their parents as their primary source of attachment support and would consider themselves as a much less significant source of attachment support.[103]

Attachment styles in adults

[edit]Attachment theory was extended to adult romantic relationships in the late 1980s by Cindy Hazan and Phillip Shaver.[104] Four styles of attachment have been identified in adults: secure, anxious-preoccupied, dismissive-avoidant and fearful-avoidant. These roughly correspond to infant classifications: secure, insecure-ambivalent, insecure-avoidant and disorganized/disoriented.[105]

Securely attached

[edit]Securely attached adults have been "linked to a high need for achievement and a low fear of failure (Elliot & Reis, 2003)". They will positively approach a task with the goal of mastering it and have an appetite for exploration in achievement settings (Elliot & Reis, 2003). Research shows that securely attached adults have a "low level of personal distress and high levels of concern for others".[106] Due to their high rates of self-efficacy, securely attached adults typically do not hesitate to remove a person having a negative impact from problematic situations they are facing.[106] This calm response is representative of the securely attached adult's emotionally regulated response to threats that many studies have supported in the face of diverse situations. Adult secure attachment comes from an individual's early connection with their caregiver(s), genes and their romantic experiences.[107]

Within romantic relationships, a securely attached adult will appear in the following ways: excellent conflict resolution, mentally flexible, effective communicators, avoidance of manipulation, comfortable with closeness without fearfulness of being enmeshed, quickly forgiving, viewing sex and emotional intimacy as one, believing they can positively impact their relationship, and caring for their partner in the way they want to be cared for. In summation, they are great partners who treat their spouses very well, as they are not afraid to give positively and ask for their needs to be met. Securely attached adults believe that there are "many potential partners that would be responsive to their needs", and if they come across an individual who is not meeting their needs, they will typically lose interest quickly.[107]

Anxious-preoccupied

[edit]Anxious-preoccupied adults seek high levels of intimacy, approval and responsiveness from partners, becoming overly dependent. They tend to be less trusting, have less positive views about themselves than their partners, and may exhibit high levels of emotional expressiveness, worry and impulsiveness in their relationships. The anxiety that adults feel prevents the establishment of satisfactory defense exclusion. Thus, it is possible that individuals that have been anxiously attached to their attachment figure or figures have not been able to develop sufficient defenses against separation anxiety. Because of their lack of preparation these individuals will then overreact to the anticipation of separation or the actual separation from their attachment figure. The anxiety comes from an individual's intense and/or unstable relationship that leaves the anxious or preoccupied individual relatively defenseless.[108]

In terms of adult relationships, if an adult experiences this inconsistent behavior from their romantic partner or acquaintance, they might develop some of the aspects of this attachment type. Besides, insecurity and distress about relationships can be driven by individuals who exhibit inconsistent connection or emotionally abusive behaviours.[109]

Dismissive-avoidant

[edit]Dismissive-avoidant adults desire a high level of independence, often appearing to avoid attachment altogether.[110] They view themselves as self-sufficient, invulnerable to attachment feelings and not needing close relationships.[111] They tend to suppress their feelings, dealing with conflict by distancing themselves from partners of whom they often have a poor opinion.[112] Adults lack the interest of forming close relationships and maintaining emotional closeness with the people around them. They have a great amount of distrust in others but at the same time possess a positive model of self, they would prefer to invest in their own ego skills. They try to create high levels of self-esteem by investing disproportionately in their abilities or accomplishments. These adults maintain their positive views of self, based on their personal achievements and competence rather than searching for and feeling acceptance from others. These adults will explicitly reject or minimize the importance of emotional attachment and passively avoid relationships when they feel as though they are becoming too close. They strive for self-reliance and independence. When it comes to the opinions of others about themselves, they are very indifferent and are relatively hesitant to positive feedback from their peers. Dismissive avoidance can also be explained as the result of defensive deactivation of the attachment system to avoid potential rejection, or genuine disregard for interpersonal closeness.[113]

Adults with dismissive-avoidant patterns are less likely to seek social support than other attachment styles.[114] They are likely to fear intimacy and lack confidence in others.[115][116] Because of their distrust they cannot be convinced that other people have the ability to deliver emotional support.[113] Under a high cognitive load, however, dismissive-avoidant adults appear to have a lowered ability to suppress difficult attachment-related emotions, as well difficulty maintaining positive self-representations.[117] This suggests that hidden vulnerabilities may underlie an active denial process.[117][118]

Fearful-avoidant

[edit]Fearful-avoidant adults have mixed feelings about close relationships, both desiring and feeling uncomfortable with emotional closeness. The dangerous part about the contrast between wanting to form social relationships while simultaneously fearing the relationship is that it creates mental instability. This mental instability then translates into mistrusting the relationships they do form and also viewing themselves as unworthy. Furthermore, fearful-avoidant adults also have a less pleasant outlook on life compared to anxious-preoccupied and dismissive avoidant groups.[119] Like dismissive-avoidant adults, fearful-avoidant adults tend to seek less intimacy, suppressing their feelings.[8][120][121][122]

According to research studies, an individual with a fearful avoidant attachment might have had childhood trauma or persistently negative perceptions and actions from their family members. Apart from these, genetic factors and personality may also have an impact on how an individual behaves with parents as well as how they understand their relationships in their adulthood.[123]

Relationships involving people with different attachment styles

[edit]Relationally, insecure individuals tend to be partnered with insecure individuals, and secure individuals with secure individuals. Insecure relationships tend to be enduring but less emotionally satisfying compared to the relationship(s) of two securely attached individuals.[124]

Attachment styles are activated from the first date onward and impact relationship dynamics and how a relationship ends. Secure attachment has been shown to allow for better conflict resolution in a relationship and for one's ability to exit an unsatisfying relationship compared to other attachment types. Secure individuals' authentic high self-esteem and positive view of others allows for this as they are confident that they will find another relationship. Secure attachment has also shown to allow for the successful processing of relational losses (e.g. death, rejection, infidelity, abandonment etc.) Attachment has also been shown to impact caregiving behavior in relationships (Shaver & Cassidy, 2018).

Assessing and measuring attachment

[edit]Two main aspects of adult attachment have been studied. The organization and stability of the mental working models that underlie the attachment styles is explored by social psychologists interested in romantic attachment.[125][126] Developmental psychologists interested in the individual's state of mind with respect to attachment generally explore how attachment functions in relationship dynamics and impacts relationship outcomes. The organization of mental working models is more stable while the individual's state of mind with respect to attachment fluctuates more. Some authors have suggested that adults do not hold a single set of working models. Instead, on one level they have a set of rules and assumptions about attachment relationships in general. On another level they hold information about specific relationships or relationship events. Information at different levels need not be consistent. Individuals can therefore hold different internal working models for different relationships.[126][127]

There are a number of different measures of adult attachment, the most common being self-report questionnaires and coded interviews based on the Adult Attachment Interview. The various measures were developed primarily as research tools, for different purposes and addressing different domains, for example romantic relationships, platonic relationships, parental relationships or peer relationships. Some classify an adult's state of mind with respect to attachment and attachment patterns by reference to childhood experiences, while others assess relationship behaviours and security regarding parents and peers.[128]

Associations of adult attachment with other traits

[edit]Adult attachment styles are related to individual differences in the ways in which adults experience and manage their emotions. Recent meta-analyses link insecure attachment styles to lower emotional intelligence[129] and lower trait mindfulness.[130]

History

[edit]Maternal deprivation

[edit]The early thinking of the object relations school of psychoanalysis, particularly Melanie Klein, influenced Bowlby. However, he profoundly disagreed with the prevalent psychoanalytic belief that infants' responses relate to their internal fantasy life rather than real-life events. As Bowlby formulated his concepts, he was influenced by case studies on disturbed and delinquent children, such as those of William Goldfarb published in 1943 and 1945.[131][132]

Bowlby's contemporary René Spitz observed separated children's grief, proposing that "psychotoxic" results were brought about by inappropriate experiences of early care.[134][135] A strong influence was the work of social worker and psychoanalyst James Robertson who filmed the effects of separation on children in hospital. He and Bowlby collaborated in making the 1952 documentary film A Two-Year Old Goes to the Hospital which was instrumental in a campaign to alter hospital restrictions on visits by parents.[136]

In his 1951 monograph for the World Health Organization, Maternal Care and Mental Health, Bowlby put forward the hypothesis that "the infant and young child should experience a warm, intimate, and continuous relationship with his mother in which both find satisfaction and enjoyment", the lack of which may have significant and irreversible mental health consequences. This was also published as Child Care and the Growth of Love for public consumption. The central proposition was influential but highly controversial.[137] At the time there was limited empirical data and no comprehensive theory to account for such a conclusion.[138] Nevertheless, Bowlby's theory sparked considerable interest in the nature of early relationships, giving a strong impetus to, (in the words of Mary Ainsworth), a "great body of research" in an extremely difficult, complex area.[137]

Bowlby's work (and Robertson's films) caused a virtual revolution in a hospital visiting by parents, hospital provision for children's play, educational and social needs, and the use of residential nurseries. Over time, orphanages were abandoned in favour of foster care or family-style homes in most developed countries.[133]

Bowlby's work about parental provisions after child birth implicates that maternal deprivation negatively influences the attachment behavior trajectory of a child's life. If a mother experiences post-partum anxiety, stress, or depression, the attachment they have with their child can be disrupted. It is important for pregnant women to have mental-health support pre and post-partum because mental illness often results in low feelings of attachment to their infant.[139]

Formulation of the theory

[edit]Following the publication of Maternal Care and Mental Health, Bowlby sought new understanding from the fields of evolutionary biology, ethology, developmental psychology, cognitive science and control systems theory. He formulated the innovative proposition that mechanisms underlying an infant's emotional tie to the caregiver(s) emerged as a result of evolutionary pressure. He set out to develop a theory of motivation and behaviour control built on science rather than Freud's psychic energy model. Bowlby argued that with attachment theory he had made good the "deficiencies of the data and the lack of theory to link alleged cause and effect" of Maternal Care and Mental Health.[140]

Ethology

[edit]Bowlby's attention was drawn to ethology in the early 1950s when he read Konrad Lorenz's work.[141] Other important influences were ethologists Nikolaas Tinbergen and Robert Hinde.[142] Bowlby subsequently collaborated with Hinde.[143] In 1953 Bowlby stated "the time is ripe for a unification of psychoanalytic concepts with those of ethology, and to pursue the rich vein of research which this union suggests."[144] Konrad Lorenz had examined the phenomenon of "imprinting", a behaviour characteristic of some birds and mammals which involves rapid learning of recognition by the young, of a conspecific or comparable object. After recognition comes a tendency to follow.

Certain types of learning are possible, respective to each applicable type of learning, only within a limited age range known as a critical period. Bowlby's concepts included the idea that attachment involved learning from experience during a limited age period, influenced by adult behaviour. He did not apply the imprinting concept in its entirety to human attachment. However, he considered that attachment behaviour was best explained as instinctive, combined with the effect of experience, stressing the readiness the child brings to social interactions.[145] Over time it became apparent there were more differences than similarities between attachment theory and imprinting so the analogy was dropped.[10]

Ethologists expressed concern about the adequacy of some research on which attachment theory was based, particularly the generalization to humans from animal studies.[146][147] Schur, discussing Bowlby's use of ethological concepts (pre-1960) commented that concepts used in attachment theory had not kept up with changes in ethology itself.[148] Ethologists and others writing in the 1960s and 1970s questioned and expanded the types of behaviour used as indications of attachment.[149] Observational studies of young children in natural settings provided other behaviours that might indicate attachment; for example, staying within a predictable distance of the mother without effort on her part and picking up small objects, bringing them to the mother but not to others.[150] Although ethologists tended to be in agreement with Bowlby, they pressed for more data, objecting to psychologists writing as if there were an "entity which is 'attachment', existing over and above the observable measures."[151] Robert Hinde considered "attachment behaviour system" to be an appropriate term which did not offer the same problems "because it refers to postulated control systems that determine the relations between different kinds of behaviour."[152]

Psychoanalysis

[edit]

Psychoanalytic concepts influenced Bowlby's view of attachment, in particular, the observations by Anna Freud and Dorothy Burlingham of young children separated from familiar caregivers during World War II.[153] However, Bowlby rejected psychoanalytical explanations for early infant bonds including "drive theory" in which the motivation for attachment derives from gratification of hunger and libidinal drives. He called this the "cupboard-love" theory of relationships. In his view it failed to see attachment as a psychological bond in its own right rather than an instinct derived from feeding or sexuality.[154] Based on ideas of primary attachment and Neo-Darwinism, Bowlby identified what he saw as fundamental flaws in psychoanalysis: the overemphasis of internal dangers rather than external threat, and the view of the development of personality via linear phases with regression to fixed points accounting for psychological distress. Bowlby instead posited that several lines of development were possible, the outcome of which depended on the interaction between the organism and the environment. In attachment this would mean that although a developing child has a propensity to form attachments, the nature of those attachments depends on the environment to which the child is exposed.[155]

From early in the development of attachment theory there was criticism of the theory's lack of congruence with various branches of psychoanalysis. Bowlby's decisions left him open to criticism from well-established thinkers working on similar problems.[156][157][158]

Internal working model

[edit]The philosopher Kenneth Craik had noted the ability of thought to predict events. He stressed the survival value of natural selection for this ability. A key component of attachment theory is the attachment behaviour system where certain behaviours have a predictable outcome (i.e. proximity) and serve as self-preservation method (i.e. protection).[159] All taking place outside of an individual's awareness, This internal working model allows a person to try out alternatives mentally, using knowledge of the past while responding to the present and future. Bowlby applied Craik's ideas to attachment, when other psychologists were applying these concepts to adult perception and cognition.[160]

Infants absorb all sorts of complex social-emotional information from the social interactions that they observe. They notice the helpful and hindering behaviours of one person to another. From these observations they develop expectations of how two characters should behave, known as a "secure base script." These scripts provide as a template of how attachment related events should unfold and they are the building blocks of ones internal working models.[159] An infant's internal working model is developed in response to the infant's experience based internal working models of self, and environment, with emphasis on the caregiving environment and the outcomes of his or her proximity-seeking behaviours. Theoretically, secure child and adult script, would allow for an attachment situation where one person successfully utilizes another as a secure base from which to explore and as a safe haven in times of distress. In contrast, insecure individuals would create attachment situations with more complications.[159] For example, If the caregiver is accepting of these proximity-seeking behaviours and grants access, the infant develops a secure organization; if the caregiver consistently denies the infant access, an avoidant organization develops; and if the caregiver inconsistently grants access, an ambivalent organization develops.[161] In retrospect, internal working models are constant with and reflect the primary relationship with our caregivers. Childhood attachment directly influences our adult relationships.[162]

A parent's internal working model that is operative in the attachment relationship with her infant can be accessed by examining the parent's mental representations.[163][164] Recent research has demonstrated that the quality of maternal attributions as markers of maternal mental representations can be associated with particular forms of maternal psychopathology and can be altered in a relative short time-period by targeted psychotherapeutic intervention.[165]

Cybernetics

[edit]The theory of control systems (cybernetics), developing during the 1930s and 1940s, influenced Bowlby's thinking.[166] The young child's need for proximity to the attachment figure was seen as balancing homeostatically with the need for exploration. (Bowlby compared this process to physiological homeostasis whereby, for example, blood pressure is kept within limits). The actual distance maintained by the child would vary as the balance of needs changed. For example, the approach of a stranger, or an injury, would cause the child exploring at a distance to seek proximity. The child's goal is not an object (the caregiver) but a state; maintenance of the desired distance from the caregiver depending on circumstances.[1]

Cognitive development

[edit]Bowlby's reliance on Piaget's theory of cognitive development gave rise to questions about object permanence (the ability to remember an object that is temporarily absent) in early attachment behaviours. An infant's ability to discriminate strangers and react to the mother's absence seemed to occur months earlier than Piaget suggested would be cognitively possible.[167] More recently, it has been noted that the understanding of mental representation has advanced so much since Bowlby's day that present views can be more specific than those of Bowlby's time.[168]

Behaviourism

[edit]In 1969, Gerwitz discussed how mother and child could provide each other with positive reinforcement experiences through their mutual attention, thereby learning to stay close together. This explanation would make it unnecessary to posit innate human characteristics fostering attachment.[169] Learning theory, (behaviourism), saw attachment as a remnant of dependency with the quality of attachment being merely a response to the caregiver's cues. The main predictors of attachment quality are parents being sensitive and responsive to their children. When parents interact with their infants in a warm and nurturing manner, their attachment quality increases. The way that parents interact with their children at four months is related to attachment behavior at 12 months, thus it is important for parents' sensitivity and responsiveness to remain stable. The lack of sensitivity and responsiveness increases the likelihood for attachment disorders to development in children.[170] Behaviourists saw behaviours like crying as a random activity meaning nothing until reinforced by a caregiver's response. To behaviourists, frequent responses would result in more crying. To attachment theorists, crying is an inborn attachment behaviour to which the caregiver must respond if the infant is to develop emotional security. Conscientious responses produce security which enhances autonomy and results in less crying. Ainsworth's research in Baltimore supported the attachment theorists' view.[171]

In the last decade, behaviour analysts have constructed models of attachment based on the importance of contingent relationships. These behaviour analytic models have received some support from research[172] and meta-analytic reviews.[173]

Developments since 1970s

[edit]In the 1970s, problems with viewing attachment as a trait (stable characteristic of an individual) rather than as a type of behaviour with organizing functions and outcomes, led some authors to the conclusion that attachment behaviours were best understood in terms of their functions in the child's life.[174] This way of thinking saw the secure base concept as central to attachment theory's logic, coherence, and status as an organizational construct.[175] Following this argument, the assumption that attachment is expressed identically in all humans cross-culturally was examined.[176] The research showed that though there were cultural differences, the three basic patterns, secure, avoidant and ambivalent, can be found in every culture in which studies have been undertaken, even where communal sleeping arrangements are the norm. The selection of the secure pattern is found in the majority of children across cultures studied. This follows logically from the fact that attachment theory provides for infants to adapt to changes in the environment, selecting optimal behavioural strategies.[177] How attachment is expressed shows cultural variations which need to be ascertained before studies can be undertaken; for example Gusii infants are greeted with a handshake rather than a hug. Securely attached Gusii infants anticipate and seek this contact. There are also differences in the distribution of insecure patterns based on cultural differences in child-rearing practices.[177] The scholar Michael Rutter in 1974 studied the importance of distinguishing between the consequences of attachment deprivation upon intellectual retardation in children and lack of development in the emotional growth in children.[178] Rutter's conclusion was that a careful delineation of maternal attributes needed to be identified and differentiated for progress in the field to continue.

The biggest challenge to the notion of the universality of attachment theory came from studies conducted in Japan where the concept of amae plays a prominent role in describing family relationships. Arguments revolved around the appropriateness of the use of the Strange Situation procedure where amae is practiced. Ultimately research tended to confirm the universality hypothesis of attachment theory.[177] Most recently a 2007 study conducted in Sapporo in Japan found attachment distributions consistent with global norms using the six-year Main and Cassidy scoring system for attachment classification.[179][180]

Critics in the 1990s such as J. R. Harris, Steven Pinker and Jerome Kagan were generally concerned with the concept of infant determinism (nature versus nurture), stressing the effects of later experience on personality.[181][182][183] Building on the work on temperament of Stella Chess, Kagan rejected almost every assumption on which attachment theory's cause was based. Kagan argued that heredity was far more important than the transient developmental effects of early environment. For example, a child with an inherently difficult temperament would not elicit sensitive behavioural responses from a caregiver. The debate spawned considerable research and analysis of data from the growing number of longitudinal studies. Subsequent research has not borne out Kagan's argument, possibly suggesting that it is the caregiver's behaviours that form the child's attachment style, although how this style is expressed may differ with the child's temperament.[184] Harris and Pinker put forward the notion that the influence of parents had been much exaggerated, arguing that socialization took place primarily in peer groups. H. Rudolph Schaffer concluded that parents and peers had different functions, fulfilling distinctive roles in children's development.[185]

Psychoanalyst/psychologists Peter Fonagy and Mary Target have attempted to bring attachment theory and psychoanalysis into a closer relationship through cognitive science as mentalization. Mentalization, or theory of mind, is the capacity of human beings to guess with some accuracy what thoughts, emotions and intentions lie behind behaviours as subtle as facial expression.[186] It has been speculated that this connection between theory of mind and the internal working model may open new areas of study, leading to alterations in attachment theory.[187] Since the late 1980s, there has been a developing rapprochement between attachment theory and psychoanalysis, based on common ground as elaborated by attachment theorists and researchers, and a change in what psychoanalysts consider to be central to psychoanalysis. Object relations models which emphasise the autonomous need for a relationship have become dominant and are linked to a growing recognition in psychoanalysis of the importance of infant development in the context of relationships and internalized representations. Psychoanalysis has recognized the formative nature of a child's early environment including the issue of childhood trauma. A psychoanalytically based exploration of the attachment system and an accompanying clinical approach has emerged together with a recognition of the need for measurement of outcomes of interventions.[188]

One focus of attachment research has been the difficulties of children whose attachment history was poor, including those with extensive non-parental child care experiences. Concern with the effects of child care was intense during the so-called "day care wars" of the late-20th century, during which some authors stressed the deleterious effects of day care.[189] As a result of this controversy, training of child care professionals has come to stress attachment issues, including the need for relationship-building by the assignment of a child to a specific care-giver. Although only high-quality child care settings are likely to provide this, more infants in child care receive attachment-friendly care than in the past.[190] A natural experiment permitted extensive study of attachment issues as researchers followed thousands of Romanian orphans adopted into Western families after the end of the Nicolae Ceaușescu regime. The English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team, led by Michael Rutter, followed some of the children into their teens, attempting to unravel the effects of poor attachment, adoption, new relationships, physical problems and medical issues associated with their early lives. Studies of these adoptees, whose initial conditions were shocking, yielded reason for optimism as many of the children developed quite well. Researchers noted that separation from familiar people is only one of many factors that help to determine the quality of development.[191] Although higher rates of atypical insecure attachment patterns were found compared to native-born or early-adopted samples, 70% of later-adopted children exhibited no marked or severe attachment disorder behaviours.[89]

Authors considering attachment in non-Western cultures have noted the connection of attachment theory with Western family and child care patterns characteristic of Bowlby's time.[192] As children's experience of care changes, so may attachment-related experiences. For example, changes in attitudes toward female sexuality have greatly increased the numbers of children living with their never-married mothers or being cared for outside the home while the mothers work. This social change has made it more difficult for childless people to adopt infants in their own countries. There has been an increase in the number of older-child adoptions and adoptions from third-world sources in first-world countries. Adoptions and births to same-sex couples have increased in number and gained legal protection, compared to their status in Bowlby's time.[193] Regardless of whether parents are genetically related, adoptive parents attachment roles they will still influence and affect their child's attachment behaviors throughout their lifetime.[194] Issues have been raised to the effect that the dyadic model characteristic of attachment theory cannot address the complexity of real-life social experiences, as infants often have multiple relationships within the family and in child care settings.[195] It is suggested these multiple relationships influence one another reciprocally, at least within a family.[196]

Principles of attachment theory have been used to explain adult social behaviours, including mating, social dominance and hierarchical power structures, in-group identification,[197] group coalitions, membership in cults and totalitarian systems[198] and negotiation of reciprocity and justice.[199] Those explanations have been used to design parental care training, and have been particularly successful in the design of child abuse prevention programmes.[200]

While a wide variety of studies have upheld the basic tenets of attachment theory, research has been inconclusive as to whether self-reported early attachment and later depression are demonstrably related.[201]

Neurobiology of attachment

[edit]In addition to longitudinal studies, there has been psychophysiological research on the neurobiology of attachment.[202] Research has begun to include neural development,[203] behaviour genetics and temperament concepts.[184] Generally, temperament and attachment constitute separate developmental domains, but aspects of both contribute to a range of interpersonal and intrapersonal developmental outcomes.[184] Some types of temperament may make some individuals susceptible to the stress of unpredictable or hostile relationships with caregivers in the early years.[204] In the absence of available and responsive caregivers it appears that some children are particularly vulnerable to developing attachment disorders.[205]

The quality of caregiving received at infancy and childhood directly affects an individual's neurological systems which controls stress regulation.[202] In psychophysiological research on attachment, the two main areas studied have been autonomic responses, such as heart rate or respiration, and the activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, a system that is responsible for the body's reaction to stress.[206] Infants' physiological responses have been measured during the Strange Situation procedure looking at individual differences in infant temperament and the extent to which attachment acts as a moderator. Recent studies convey that early attachment relationships become molecularly instilled into the being, thus affecting later immune system functioning.[159] Empirical evidence communicates that early negative experiences produce pro inflammatory phenotype cells in the immune system, which is directly related to cardiovascular disease, autoimmune diseases, and certain types of cancer.[207]

Recent[when?] improvements involving methods of research have enabled researchers to further investigate the neural correlates of attachment in humans. These advances include identifying key brain structures, neural circuits, neurotransmitter systems, and neuropeptides, and how they are involved in attachment system functioning and can indicate more about a certain individual, even predict their behaviour.[208] There is initial evidence that caregiving and attachment involve both unique and overlapping brain regions.[209] Another issue is the role of inherited genetic factors in shaping attachments: for example one type of polymorphism of the gene coding for the D2 dopamine receptor has been linked to anxious attachment and another in the gene for the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor with avoidant attachment.[210]