Eli Lilly

This article may contain citations that do not verify the text. The reason given is: See Featured article review and article talk page (January 2023) |

Eli Lilly | |

|---|---|

Lilly in 1885 | |

| Born | July 8, 1838 Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Died | June 6, 1898 (aged 59) Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S. |

| Resting place | Crown Hill Cemetery, Indianapolis, Indiana |

| Education | Pharmacology |

| Alma mater | Indiana Asbury University |

| Occupations | |

| Known for | |

| Title | Colonel |

| Political party | Republican |

| Board member of | Grand Army of the Republic |

| Spouse(s) |

Emily Lemen

(m. 1860; died 1866)Maria Cynthia Sloan (m. 1869) |

| Children | Josiah K. Lilly Sr. Eleanor Lilly |

| Relatives | Eli Lilly Jr. (grandson) Josiah K. Lilly Jr. (grandson) |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ | Union Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Regiments | 21st Indiana Infantry Regiment 18th Indiana Light Artillery 9th Indiana Cavalry (121st Indiana Infantry Regiment) |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War: Battle of Hoover's Gap, Second Battle of Chattanooga, Battle of Chickamauga, Atlanta Campaign, Battle of Resaca, Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, Battle of Sulphur Creek Trestle |

| Signature | |

| |

Eli Lilly (July 8, 1838 – June 6, 1898) was an Union Army officer, pharmacist, chemist, and businessman who founded Eli Lilly and Company.

Lilly enlisted in the Union Army during the American Civil War and recruited a company of men to serve with him in the 18th Independent Battery Indiana Light Artillery. He was later promoted to major and then colonel, and was given command of the 9th Indiana Infantry Regiment. Lilly was captured in September 1864 and held as a prisoner of war until January 1865. After the war, he attempted to run a plantation in Mississippi, but it failed and he returned to his pharmacy profession after the death of his first wife.

Lilly remarried and worked with business partners in several pharmacies in Indiana and Illinois before opening his own business in 1876 in Indianapolis. Lilly's company manufactured drugs and marketed them on a wholesale basis to pharmacies. Lilly's pharmaceutical firm proved to be successful and he soon became wealthy after making numerous advances in medicinal drug manufacturing. Two of the early advances he pioneered were creating gelatin capsules to contain medicines and developing fruit flavorings. Eli Lilly and Company became one of the first pharmaceutical firms of its kind to staff a dedicated research department and put into place numerous quality-assurance measures.

Using his wealth, Lilly engaged in numerous philanthropic pursuits. He turned over the management of the company to his son, Josiah K. Lilly Sr., around 1890 to allow himself more time to continue his involvement in charitable organizations and civic advancement. Colonel Lilly helped found the Commercial Club, the forerunner to the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce and became the primary patron of Indiana's branch of the Charity Organization Society. He personally funded a children's hospital in Indianapolis, known as Eleanor Hospital (closed in 1909). Lilly continued his active involvement with many other organizations until his death from cancer in 1898.

Colonel Lilly was an advocate of federal regulation of the pharmaceutical industry, and many of his suggested reforms were enacted into law in 1906, resulting in the creation of the Food and Drug Administration. He was also among the pioneers of the concept of prescriptions, and helped form what became the common practice of giving addictive or dangerous medicines only to people who had first seen a physician. The company he founded has since grown into one of the largest and most influential pharmaceutical corporations in the world, and the largest corporation in Indiana. Using the wealth generated by the company, his son, J. K., and grandsons, Eli Jr. and Josiah Jr. (Joe), established the Lilly Endowment in 1937. It remains as one of the largest charitable benefactors in the world and continues the Lilly legacy of philanthropy.

Early life and education

[edit]Lilly was born on July 8, 1838, in Baltimore, Maryland, the first of eleven children born to Gustavus and Esther (Kirby) Lilly.[1] His family, who were partly of Swedish descent, moved to the low country of France before his great-grandparents immigrated to Maryland in 1789.[2] As an infant, the family moved to Kentucky, where they eventually settled on a farm near Warsaw in Gallatin County.[3][4][5]

In 1852, the family settled at Greencastle, Indiana,[6] where Lilly's parents enrolled him at Indiana Asbury University, later renamed DePauw University, where he attended from 1852 to 1854. He also assisted at a local printing press as a printer's devil.[4][7] Lilly grew up in a Methodist household, and his family was prohibitionist and anti-slavery; their beliefs were part of their motivation to move to Indiana.[3] Lilly and his family were members of the Democratic Party during his early life, but became Republicans prior to the American Civil War.[8]

Lilly became interested in chemicals as a teen. In 1854, while on a trip to visit his aunt and uncle in Lafayette, Indiana, the 16-year-old Lilly visited Henry Lawrence's Good Samaritan Drug Store, a local apothecary shop, where he watched Lawrence prepare pharmaceutical drugs.[9] Lilly completed a four-year apprenticeship with Lawrence to become a chemist and pharmacist. In addition to learning to mix chemicals, Lawrence taught Lilly how to manage funds and operate a business.

Career

[edit]In 1858, after earning a certificate of proficiency from his apprenticeship, Lilly left the Good Samaritan to work for Israel Spencer and Sons, a wholesale and retail druggist in Lafayette, before moving to Indianapolis to take a position at the Perkins and Coons Pharmacy.[4][10][11]

In 1860, Lilly returned to Greencastle, Indiana, where he worked in Jerome Allen's drugstore. He opened his own drugstore in the city in January 1861, and married Emily Lemen, the daughter of a Greencastle merchant, on January 31, 1861.[10][11] During the early years of their marriage, the couple resided in Greenfield.[4][10][11] The couple's son, Josiah Kirby, later called "J. K.", was born on November 18, 1861, while Eli was serving in the military during the American Civil War.[3][12]

American Civil War

[edit]

In 1861, a few months after the start of the American Civil War, Lilly enlisted in the Union Army and joined the 21st Indiana Infantry Regiment on July 24. Lilly was commissioned as a second lieutenant on July 29, 1861. On August 3, the 21st Regiment reached Baltimore, where it remained for several months. Lilly resigned his commission in December 1861, and returned to Indiana to form an artillery unit.[4][13]

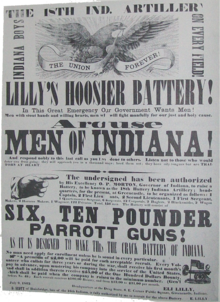

In early 1862, Lilly actively recruited volunteers for his unit among his classmates, friends, local merchants, and farmers. He had recruitment posters created and posted them around Indianapolis, promising to form the "crack battery of Indiana".[7] His unit, the 18th Independent Battery Indiana Light Artillery, was known as the Lilly Battery and consisted of six, three-inch ordinance rifles and 150 men. Lilly was commissioned as a captain in the unit. The 18th Indiana mustered into service at Camp Morton in Indianapolis on August 6, 1862, and spent a brief time drilling before it was sent into battle under Major General William Rosecrans in Kentucky and Tennessee. Lilly's artillery unit was transferred to the Lightning Brigade, a mounted infantry under the command of Colonel, later General, John T. Wilder on December 16, 1862.[3][4][7]

Lilly was elected to serve as the commanding officer of his battery from August 1862 until the winter of 1863, when his three-year enlistment expired. His only prior military experience had been in a Lafayette, Indiana, militia unit. Several of his artillerymen considered him too young and intemperate to command; however, despite his initial inexperience, Lilly became a competent artillery officer. His battery was instrumental in several battles, including the Battle of Hoover's Gap in June 1863, the Second Battle of Chattanooga in August 1863, and the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863.[4][10]

In 1864, when Lilly's term of enlistment ended, he resigned his commission and left the 18th Indiana. Lilly joined the 9th Indiana Cavalry (121st Regiment Indiana Volunteers) and was promoted to major.

In September 1864, at the Battle of Sulphur Creek Trestle in Alabama, he was captured by Confederate troops under the command of Major General Nathan B. Forrest and held in a prisoner-of-war camp at Enterprise, Mississippi until his release in a prisoner exchange in January 1865. Lilly was promoted to colonel on June 4, 1865, and was stationed at Vicksburg, Mississippi, in the spring of 1865 when the Civil War ended.[3][4][14] In recognition of his service, he was brevetted to the rank of lieutenant colonel and mustered out of service with the 9th Indiana Cavalry on August 25, 1865.[7][14][15]

Lilly later obtained a large atlas, and marked the path of his movements during the Civil War and the location of battles and skirmishes in which he participated. He often used the atlas when telling war stories.[16] His colonel's title stayed with him for the rest of his life, and his friends and family used it as a nickname for him. In 1893, Lilly served as chairman of the Grand Army of the Republic, a brotherhood of Union Civil War veterans. During his term, he helped organize an event that brought tens of thousands of Union Army veterans, including Lilly's battery, together in Indianapolis for a reunion and a large parade.[8][10]

Early business ventures

[edit]After the end of the Civil War, Lilly remained in the South to begin a new business venture. Lilly and his business partner leased Bowling Green, a 1,200-acre (490 ha) cotton plantation in Mississippi. Lilly traveled to Greencastle, Indiana, and returned with his wife, Emily, his sister, Anna Wesley Lilly, and son, Josiah.[4][17] Shortly after the move the entire family was stricken with a mosquito-borne disease, probably malaria, that was common in the region at that time. Although the others recovered, Emily died on August 20, 1866, eight months pregnant with a second son, who was stillborn. The death devastated Lilly; he wrote to his family, "I can hardly tell you how it glares at me ...it's a bitter, bitter truth ... Emily is indeed dead."[3][18] Lilly abandoned the plantation and returned to Indiana. The plantation fell into disrepair and a drought caused its cotton crop to fail. Lilly's business partner, unable to maintain the plantation because of the drought, disappeared with the venture's remaining cash. Lilly was forced to file for bankruptcy in 1868.[11]

Lilly worked to resolve the situation on the plantation and find other employment while his young son, Josiah, lived with Colonel Lilly's parents in Greencastle.[19] In 1867, Lilly found work at the Harrison Daily and Company, a wholesale drug firm. In 1869, he began working for Patterson, Moore and Talbott, another medicinal wholesale company, before he moved to Illinois to establish a new business.[10] In 1869, Lilly left Indiana to open a drugstore with James W. Binford, his business partner. Binford and Lilly opened The Red Front Drugstore in Paris, Illinois, in August 1869.[19]

In November 1869, Colonel Lilly married Maria Cynthia Sloan. Soon after their marriage they sent for his son, Josiah, who was still living in Greencastle, to join them in Illinois.[3][19] Eli and Maria's only child, a daughter named Eleanor, was born on January 25, 1871, and died of diphtheria in 1884 at the age of thirteen.[4][20] Maria died in 1932.

Although the business in Illinois was profitable and allowed Lilly to save money, he was more interested in medicinal manufacturing than running a pharmacy. Lilly began formulating a plan to create a medicinal wholesale company of his own. Lilly left the partnership with Binford in 1873 to return to Indianapolis, where, on January 1, 1874, he and John F. Johnston opened a drug manufacturing operation called Johnston and Lilly. Three years later, on March 27, 1876, Lilly dissolved the partnership. His share of the assets amounted to an estimated $400 in merchandise (several pieces of equipment and a few gallons of unmixed chemicals) and about $1,000 in cash.[4][19]

When Lilly approached Augustus Keifer, a wholesale druggist and family friend, for a job, Keifer encouraged Lilly to established his own drug manufacturing business in Indianapolis. Keifer and two associated drugstores agreed to purchase their drugs from Lilly at a cost lower than they were currently paying.[4][11]

Eli Lilly and Company founder

[edit]

On May 10, 1876, Lilly opened his own laboratory in a rented two-story building at 15 West Pearl Street that has since been demolished, and began to manufacture drugs. The sign for the business said "Eli Lilly, Chemist".[10][21][22] Lilly's manufacturing venture began with $1,400 ($34,024 in 2020 chained dollars) in working capital and three employees: Albert Hall (chief compounder), Caroline Kruger (bottler and product finisher), and Lilly's fourteen-year-old son, Josiah, who had quit school to work with his father as an apprentice.[3][19]

Lilly's first innovation was gelatin-coated pills and capsules. Other early innovations included fruit flavorings and sugarcoated pills, which made medicines easier to swallow.[3] Following his experience with the low-quality medicines used in the Civil War, Lilly committed himself to producing only high-quality prescription drugs, in contrast to the common and often ineffective patent medicines of the day. One of the first medicines he began to produce was quinine, a drug used to treat malaria,[23] that resulted in a "ten fold" increase in sales.[24] Lilly products gained a reputation for quality and became popular in the city. At the end of 1876, his first year of business, sales reached $4,470 ($108,635 in 2020 chained dollars), and by 1879 they had grown to $48,000 ($1,333,200 in 2020 chained dollars).[23]

As sales expanded rapidly he began to acquire customers outside of Indiana. Lilly hired his brother, James, as his first full-time salesman in 1878. James, and the subsequent sales team that developed, marketed the company's drugs nationally. Other family members were also employed by the growing company; Lilly's cousin Evan Lilly was hired as a bookkeeper and his grandsons, Eli and Josiah (Joe), were hired to run errands and perform other odd jobs. In 1881 Lilly formally incorporated the firm as Eli Lilly and Company, elected a board of directors, and issued stock to family members and close associates.[22][25] By the late 1880s Colonel Lilly had become one of the Indianapolis area's leading businessmen, with a company of more than one hundred employees and $200,000 ($5,760,741 in 2020 chained dollars) in annual sales.[10][21]

To accommodate his growing business, Lilly acquired additional facilities for research and production. Lilly's business remained at the Pearl Street location from 1876 to 1878, then moved to larger quarters at 36 South Meridian. In 1881 he purchased a complex of buildings at McCarty and Alabama Streets, south of downtown Indianapolis, and moved the company to its new headquarters. Other businesses followed and the area developed into a major industrial and manufacturing district of the city. In the early 1880s the company also began making its first, widely-successful product, called Succus Alterans (a treatment for venereal disease, types of rheumatism, and skin diseases). Sales of the product provided funds for company research and additional expansion.[22][26]

Believing that it would be an advantage for his son to gain a greater technical knowledge, Lilly sent Josiah to the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy in 1880. Upon returning to the family business in 1882, Josiah was named superintendent of the laboratory.[11][19] In 1890, Lilly turned over the day-to day management of the business to Josiah, who ran the company for thirty-four years. The company flourished despite the tumultuous economic conditions in the 1890s.[8][10] In 1894, Lilly purchased a manufacturing plant to be used solely for creating capsules. The company made several technological advances in the manufacturing process, including the automation of capsule production. Over the next few years, the company annually created tens of millions of capsules and pills.[27]

Although there were many other small pharmaceutical companies in the United States, Eli Lilly and Company distinguished itself from the others by having a permanent research staff, inventing superior techniques for the mass production of medicinal drugs, and focusing on quality.[28] At first, Lilly was the company's only researcher, but as the business grew, he established a research laboratory and employed others who were dedicated to creating new drugs.

In 1886, Lilly hired his first full-time research chemist, Ernest G. Eberhards, and botanist, Walter H. Evans.[22] The department's methods of research were based on Lilly's. He insisted on quality assurance and instituted mechanisms to ensure that the drugs being produced would be effective and perform as advertised, had the correct combination of ingredients, and had the correct dosages of medicines in each pill. He was aware of the addictive and dangerous nature of some of his drugs, and pioneered the concept of giving such drugs only to people who had first seen a physician to determine if they needed the medicine.[29][30]

Philanthropy

[edit]

By the time of his retirement from his business, around 1890, Lilly was a millionaire who had been involved in civic affairs for several years. Later in life he had become increasingly more philanthropic, granting funds to charitable groups in the city.[31]

In 1879, with a group of 25 other businessmen, Lilly began sponsoring the Charity Organization Society, and soon became the primary patron of its Indiana chapter. The society merged with other charitable organizations to form the Family Welfare Society of Indianapolis, a forerunner to the Family Service Association of Central Indiana and the United Way. The associated group organized charitable groups under a central leadership structure[32] that allowed them to easily interact and better assist people by coordinating their efforts and identifying areas with the greatest need.[23]

Lilly was interested in encouraging economic growth and general development in Indianapolis. He attempted to achieve those goals by supporting local commercial organizations financially and through his personal advocacy and promotion. In 1879 he made a proposal for a public water company to meet the needs of the city, which lead to the formation of the Indianapolis Water Company.[6][23]

In 1890, Lilly and other civic leaders founded the Commercial Club; Lilly was elected as its first president.[31] The club, renamed the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce in 1912, was the primary vehicle for Lilly's city development goals.[23] It was instrumental in making numerous advances for the city, including citywide paved streets, elevated railways to allow vehicles and people to pass beneath them, and a city sewage system. The companies that provided these services were created through private and public investments and operated at low-cost; in practice they belonged to the companies' customers, who slowly bought each company back from its initial investors. The model was later followed other regions of Indiana to establish water and electric utility companies. The Commercial Club members also helped fund the creation of parks, monuments, and memorials, as well as successfully attracted investment from other businessmen and organizations to expand Indianapolis's growing industries.[33]

After the Gas Boom began to sweep the state in the 1880s, Lilly and other Commercial Club members advocated the creation of a public corporation to pump natural gas from the ground, pipe it to Indianapolis from the Trenton Gas Field, and provide it at low cost to businesses and homes. The project led to the creation of the Consumer Gas Trust Company, which Lilly named.[23] The gas company provided low-cost heating fuel that made urban living much more desirable. The gas was further used to create electricity to run Indianapolis's first public transportation venture, a streetcar system.[34]

During the Panic of 1893, Lilly created a commission to help provide food and shelter to the poor people who were adversely affected.[31] His work with the commission led him to make a personal donation of funds and property to the Flower Mission of Indianapolis in 1895. Lilly's substantial donation allowed it to establish Eleanor Hospital, a children's hospital in Indianapolis named in honor of his deceased daughter. The hospital cared for children from families who had no money to pay for routine medical care; it closed in 1909.[35]

Lilly's friends often urged him to seek public office, and they attempted to nominate him to run for Governor of Indiana as a Republican in 1896, but he refused. Lilly shunned public office, preferring to focus his attention on his philanthropic organizations. He did regularly endorse candidates, and made substantial donations to politicians who advanced his causes.[8]

After former Indiana governor Oliver P. Morton and others suggested the creation of a memorial to Indiana's many Civil War veterans, Lilly began raising funds to build the Indiana Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument. Construction began in 1888, but the monument was not completed until 1901, three years after Lilly's death. The interior of the monument houses a civil war museum, established in 1918, that is named in Lilly's honor.[36][37]

Lilly's main residence was a large home in Indianapolis on Tennessee Street, renamed Capitol Street in 1895, where he spent most of his time. Lilly, an avid fisherman, built a family vacation cottage on Lake Wawasee near Syracuse, Indiana, in 1886 and 1867. He had enjoyed regular vacations and recreation at the lake since the early 1880s. Lilly also founded the Wawasee Golf Club in 1891. Lilly's lakeside property became a haven for the family. His son, Josiah, built his own cottage on the estate in the mid-1930s.[31][38]

Death

[edit]Lilly developed cancer in 1897, and died in his Indianapolis home on June 6, 1898. His funeral, held on June 9, was attended by thousands. His remains are interred in a large mausoleum at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.[33][39]

Legacy

[edit]

At the time of Lilly's death in 1898, Eli Lilly and Company had a product line of 2,005 items and annual sales of more than $300,000 ($9,332,400 in 2020 chained dollars).[33] His son, Josiah, inherited the company following his father's death,[19] and became its president in 1898. Josiah continued to expand its operations before passing it on to his own sons, Eli Jr. and Josiah Jr. (Joe).[40]

Lilly's son and two grandsons, as well as the Lilly company, continued the philanthropic efforts that Lilly practiced. Eli Lilly and Company played an important role in delivering medicine to the victims of the devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake.[35]

In 1937, Lilly's son and grandsons established the Lilly Endowment, which became the largest philanthropic endowment in the world in terms of assets and charitable giving in 1998. (Other endowments have since surpassed it, but it still remains among the top ten.)[24][41]

Lilly's firm grew into one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world. Under the leadership of Lilly's son, Josiah (J. K.) and two grandsons, Eli and Joe, it developed many new innovations, including the pioneering and development of insulin during the 1920s, the mass production of penicillin during the 1940s, and the promotion of advancements in mass-produced medicines. Innovation continued at the company after it was made a publicly traded corporation in 1952; it developed Humulin, Merthiolate, Prozac, and many other medicines.[8][35]

According to Forbes, Eli Lilly and Company ranked as the 243rd-largest company in the world as of 2016, with sales of $20 billion and a market value of $86 billion (USD).[42][43] It is the largest corporation and the largest charitable benefactor in Indiana.[2]

Lilly's greatest contributions to the industry were his standardized and methodical production of drugs, his dedication to research and development, and the therapeutic value of the drugs he created. As a pioneer in the modern pharmaceutical industry, many of his innovations later became standard practice. Lilly's ethical reforms, in a trade that was marked by outlandish claims of miracle medicines, began a period of rapid advancement in the development of medicinal drugs.[44] During his lifetime, Lilly had advocated for federal regulation on medicines; his son, Josiah, continued that advocacy following his father's death.[35][45]

Honors and tributes

[edit]The Colonel Eli Lilly Civil War Museum, located beneath the Sailors' and Soldiers' Monument in Indianapolis, is named in Lilly's honor. It features exhibits about Indiana during the war period and the war in general.[46]

Colonel Lilly was featured in the Indiana Historical Society exhibition, "You Are There: Eli Lilly at the Beginning," at the Eugene and Marilyn Glick Indiana History Center in Indianapolis. The temporary exhibition (October 1, 2016, to January 20, 2018) included a recreation of the first Lilly laboratory on Pearl Street in Indianapolis and a costumed interpreter portraying Lilly.[47]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "Gustavus and Esther Lilly".

- ^ a b Price, Indiana Legends, p. 58

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Price, Indiana Legends, p. 59

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Colonel Eli Lilly (1838–1898)" (PDF). Lilly Archives. January 2008. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ Kahn, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b "On-line biography". Archived from the original on August 15, 2004. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Madison, p. 1

- ^ a b c d e Price, Indiana Legends, p. 60

- ^ Hallett and Hallett, p. 313

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., p. 911

- ^ a b c d e f Hallett and Hallett, p. 314

- ^ Madison, p. 7

- ^ Terrell, v. II, pp. 197, 208–09

- ^ a b Terrell, v. III, pp. 226, 231.

- ^ Dyer, p. 1109

- ^ Madison, p. 2

- ^ Price, Legendary Hoosiers, p. 103

- ^ She was initially buried on the plantation, but her remains were later exhumed and moved to Indiana for reburial at Indianapolis's Crown Hill Cemetery. See Hallett and Hallett, p. 314.

- ^ a b c d e f g Madison, p. 6

- ^ Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., pp. 585–86.

- ^ a b Madison, p. 4

- ^ a b c d "Eli Lilly & Company" (PDF). Indiana Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 29, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Price, Indiana Legends, p. 57

- ^ a b Price, Legendary Hoosiers, p. 104

- ^ Kahn, p. 23

- ^ Madison, p. 27

- ^ Podczeck, pp. 12–13

- ^ Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., p. 540

- ^ "Milestones in Medical Research". Eli Lilly and Company. Archived from the original on March 3, 2009. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- ^ Madison, p. 3

- ^ a b c d Madison, p. 5

- ^ Justin Torres. "The Philanthropy Hall of Fame: Eli Lilly". Philanthropy Roundtable. Archived from the original on December 10, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., p. 912

- ^ Glass, p. 16

- ^ a b c d "Eli Lilly & Co". The Indianapolis Star. January 1, 2001. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ Price, Indiana Legends, pp. 59–60

- ^ Rose, p. 50

- ^ Taylor, Stevens, Ponder, and Brockman, p. 544

- ^ Wissing, Tobias, Dolan, and Ryder, pp. 69–70

- ^ Price, Indiana Legends, pp. 60–61, and Madison, pp. 83, 119–20.

- ^ "Top 100 U.S. Foundations by Asset Size". Foundation Center. Retrieved April 10, 2009.

- ^ "World's Biggest Public Companies". Forbes. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ Forbes ranked Eli Lilly and Company as the 229th largest company in the world and 152nd in the United States in 2007, with a worth of $17 billion (~$24.1 billion in 2023) (USD). See "Eli Lilly & Company (NYSE: LLY) At A Glance". Forbes. Archived from the original on April 14, 2009. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ Madison, pp. 17–18, 21

- ^ Madison, pp. 51, 112–115

- ^ "Colonel Eli Lilly Civil War Museum". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ "The Man Behind State's Most Successful Startup". Kendallville New Sun. Kendallville, Indiana: KPC News. September 9, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2016. See also Tom Alvarez, ed. (Fall 2016). "Fall Arts Guide". UNITE Indianapolis. Indianapolis: Joey Amato: 32. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bodenhamer, David J.; Robert G. Barrows, eds. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-31222-1.

- "Colonel Eli Lilly (1838-1898)" (PDF). Lilly Archives. January 2008. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- Dyer, Frederick H. (1908). A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion: Compiled and Arranged from Official Records of the Federal and Confederate Armies, Reports of the Adjutant Generals of the Several States, the Army Registers, and Other Reliable Documents and Sources. Des Moines, IA: Dyer Publishing Company. p. 1109. OCLC 08697590.

- Glass, James A.; Kohrman, David (2005). The Gas Boom of East Central Indiana. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-3963-5.

- Hallett, Anthony; Dianne Hallett (1997). Entrepreneur Magazine Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurs. New York: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-17536-6.

- Kahn, E. J. (1975). All In A Century: The First 100 Years of Eli Lilly and Company. West Cornwall, CT. pp. 15–16. OCLC 5288809.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Madison, James H (1989). Eli Lilly: A Life, 1885–1977. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. ISBN 0-87195-047-2.

- Podczeck, Fridrun; Jones, Brian E (2004). Pharmaceutical capsules. Chicago: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 0-85369-568-7.

- Price, Nelson (1997). Indiana Legends: Famous Hoosiers From Johnny Appleseed to David Letterman. Carmel, Indiana: Guild Press of Indiana. pp. 57–61. ISBN 1-57860-006-5.

- Price, Nelson (2001). Legendary Hoosiers: Famous Folks from the State of Indiana. Zionsville, Indiana: Guild Press of Indiana. ISBN 1-57860-097-9.

- Rose, Ernestine Bradford (1971). The Circle: The Center of Indianapolis. Indianapolis: Crippin Printing Corporation.

- Taylor Jr.; Robert M.; Errol Wayne Stevens; Mary Ann Ponder; Paul Brockman (1989). Indiana: A New Historical Guide. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. 544. ISBN 0-87195-048-0.

- Terrell, William H. H. (1869). Indiana in the War of the Rebellion: Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana. Vol. II. Indianapolis: State of Indiana, Office of the Adjutant General. pp. 197, 208–09.

- Wissing, Douglas A.; Marianne Tobias; Rebecca W. Dolan; Anne Ryder (2013). Crown Hill: History, Spirit, and Sanctuary. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. pp. 69–70. ISBN 9780871953018.

- "World's Biggest Public Companies". Forbes. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

External links

[edit]- "On-line biography". Archived from the original on August 15, 2004. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- "Eli Lilly & co. website". Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- Ivcevich, Kelly A. "Lilly Endowment". Community League. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved April 10, 2009.

- 1838 births

- 1898 deaths

- 19th-century American chemists

- 19th-century American pharmacists

- 19th-century American philanthropists

- 19th-century American planters

- American people of Swedish descent

- Businesspeople from Baltimore

- Businesspeople from Indianapolis

- Burials at Crown Hill Cemetery

- Deaths from cancer in Indiana

- DePauw University alumni

- Eli Lilly and Company people

- Grand Army of the Republic officials

- Indiana Republicans

- Methodists from Indiana

- Military personnel from Indiana

- People from Kentucky

- People of Indiana in the American Civil War

- Pharmaceutical company founders

- Pharmacists from Indiana

- Presidents of Eli Lilly and Company

- Philanthropists from Indiana

- Union Army colonels