DDR Holdings v. Hotels.com

| DDR Holdings v. Hotels.com | |

|---|---|

| Court | United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit |

| Full case name | DDR Holdings, LLC, plaintiff-appellee v. Hotels.com, L.P., et al., defendants, and National Leisure Group, Inc. and World Travel Holdings, Inc., defendants-appellants' |

| Argued | May 6 2014 |

| Decided | December 5 2014 |

| Citations | 773 F.3d 1245; 2014 U.S. App. LEXIS 22902; 113 U.S.P.Q.2d 1097 |

| Case history | |

| Prior history | DDR Holdings, LLC v. Hotels.com, L.P., 954 F. Supp. 2d 509 (E.D. Tex. 2013) |

| Argument | Oral argument |

| Holding | |

| Patents claims to a system that addressed a problem particular to Internet businesses by implementing unconventional computer processes were directed to patent eligible subject matter. | |

| Court membership | |

| Judges sitting | Senior Circuit Judge Haldane Robert Mayer, Circuit Judge Raymond T. Chen, and Circuit Judge Evan Wallach |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Chen, joined by Wallach |

| Dissent | Mayer |

| Laws applied | |

| 35 U.S.C. § 101 | |

DDR Holdings, LLC v. Hotels.com, L.P., 773 F.3d 1245 (Fed. Cir. 2014),[1] was the first United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decision to uphold the validity of computer-implemented patent claims after the Supreme Court's decision in Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International.[2] Both Alice and DDR Holdings are legal decisions relevant to the debate about whether software and business methods are patentable subject matter under Title 35 of the United States Code §101.[3] The Federal Circuit applied the framework articulated in Alice to uphold the validity of the patents on webpage display technology at issue in DDR Holdings.[4]

In Alice, the Supreme Court held that a computer implementation of an abstract idea, which is not itself eligible for a patent, does not by itself transform that idea into something that is patent eligible.[5] According to the Supreme Court, in order to be patent eligible, what is claimed must be more than the abstract idea. The implementation of the idea must be something beyond the "routine," "conventional" or "generic."[5] In DDR Holdings, the Federal Circuit, applying the Alice analytical framework, upheld the validity of DDR's patent on its webpage display technology.[6]

Background

[edit]DDR Holdings, LLC ("DDR") was formed by inventors Daniel D. Ross and D. Delano Ross, Jr. following the asset sale of their dot-com company, Nexchange (which was formed to utilize their invention). DDR filed a lawsuit against twelve entities including Hotels.com, National Leisure Group, World Travel Holdings, Digital River, Expedia, Travelocity.com, and Orbitz Worldwide for patent infringement. DDR settled with all but three of these defendants prior to an October 2012 jury trial in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas. The jury found that neither of the patents at issue were invalid, that National Leisure Group, Inc. and World Travel Holdings, Inc. (collectively "NLG") directly infringed both these patents, that Digital River directly infringed one of the patents, and that DDR should be awarded $750,000 in damages.[6]

Following the verdict, the district court denied defendants’ motions for Judgment as a matter of law (JMOL) and entered final judgment in favor of DDR, consistent with the jury's findings.[7][6] Defendants appealed, however, by the time of oral argument, DDR settled with Digital River, and Digital River's appeal was subsequently terminated. NLG continued its appeal.

Patents-in-suit

[edit]DDR is the assignee of U.S. Patent Nos. 7,818,399 ("the '399 patent") and 6,993,572 ("the '572 patent"), both of which are continuations of an earlier patent—U.S. Patent No. 6,629,135 ("the '135 patent").[citation needed] The court's § 101 analysis focused on the '399 patent, entitled "Methods of expanding commercial opportunities for internet websites through coordinated offsite marketing."[8]

The Invention

[edit]The '399 patent addresses a particular problem in the field of e-commerce when vendors advertise their products and services through a hosting page of an affiliate:

[Vendors] are able to lure visitor traffic away from the affiliate. Once a visitor clicks on an affiliate ad and enters an online store, that visitor has left the affiliate's site and is gone. [This presents] a fundamental drawback of the affiliate programs--the loss of the visitor to the vendor.

The '399 patent also identifies some other attempts at solving this problem:

Affiliates are able to use "frames" to keep a shell of their own website around the vendor's site, but this is only a marginally effective solution.

Some Internet affiliate sales vendors have begun placing "return to referring website" links on their order confirmation screens, an approach that is largely ineffective. This limitation of an affiliate program restricts participation to less trafficked websites that are unconcerned about losing visitors.

Search engines and directories continue to increase in their usefulness and popularity, while banner ads and old-style links continue their rapid loss of effectiveness and popular usage.

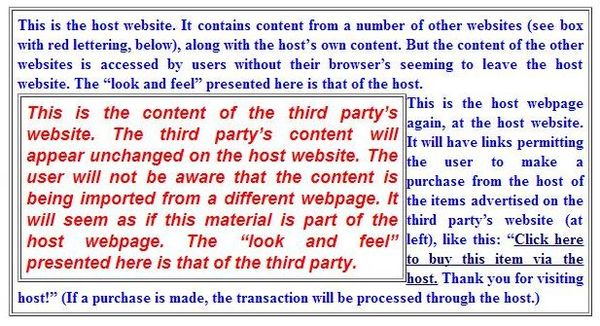

The '399 patent claims a process involving stored data concerning the visual elements responsible for the "look and feel" of the host website, where, upon clicking an ad for a third-party merchant's product, the customer is directed to a hybrid page generated by the host website that is a composite of the third-party merchant's product information and the look and feel elements of the host website. "For example, the generated composite web page may combine the logo, background color, and fonts of the host website with product information from the merchant."[6]

The Federal Circuit described the '399 patent as follows:

The patents-in-suit disclose a system that provides a solution to this problem (for the host) by creating a new web page that permits a website visitor, in a sense, to be in two places at the same time… [T]he host website can display a third-party merchant’s products, but retain its visitor traffic by displaying this product information from within a generated web page that ‘gives the viewer of the page the impression that she is viewing pages served by the host’ website." [The system] instructs an Internet web server of an “outsource provider” to construct and serve to the visitor a new, hybrid web page that merges content associated with the products of the third-party merchant with the stored “visually perceptible elements” from the identified host website.[9]

A case note states[10] that one way to accomplish the function would be with an <iframe> tag (or a <frameset> tag, which HTML5 allows but no longer supports). The court's opinions use the metaphor of the "store within a store" to describe what the invention does and how it works, stating that the inventor's idea was to have an Internet webpage that was like a warehouse store or department store (the dissenting opinion uses BJ's Wholesale Clubs as an illustrative example); other merchants' webpages would function like concessions or kiosks within the department store.[11] A commentator asserted that the court's "store within a store" metaphor may not be the best way to look at this claimed invention, and that it may be more apt to characterize what the invention does as placing a frame around someone else's webpage and incorporating the frame and its content into the host's webpage.[12] This is the effect that the invention accomplishes:

Representative claim 19 of the '399 patent recites:

- "19. A system useful in an outsource provider serving web pages offering commercial opportunities, the system comprising:

- (a) a computer store containing data, for each of a plurality of first web pages, defining a plurality of visually perceptible elements, which visually perceptible elements correspond to the plurality of first web pages;

- (i) wherein each of the first web pages belongs to one of a plurality of web page owners;

- (ii) wherein each of the first web pages displays at least one active link associated with a commerce object associated with a buying opportunity of a selected one of a plurality of merchants; and

- (iii) wherein the selected merchant, the out-source provider, and the owner of the first web page displaying the associated link are each third parties with respect to one other;

- (b) a computer server at the outsource provider, which computer server is coupled to the computer store and programmed to:

- (i) receive from the web browser of a computer user a signal indicating activation of one of the links displayed by one of the first web pages;

- (ii) automatically identify as the source page the one of the first web pages on which the link has been activated;

- (iii) in response to identification of the source page, automatically retrieve the stored data corresponding to the source page; and

- (iv) using the data retrieved, automatically generate and transmit to the web browser a second web page that displays: (A) information associated with the commerce object associated with the link that has been activated, and (B) the plurality of visually perceptible elements visually corresponding to the source page."[13]

- (a) a computer store containing data, for each of a plurality of first web pages, defining a plurality of visually perceptible elements, which visually perceptible elements correspond to the plurality of first web pages;

Legal landscape

[edit]Under US law, all patentable inventions meet several general requirements: The claimed invention must be:

- statutory subject matter[3]

- Judicial interpretation of this statute dictates that natural phenomena, laws of nature, and abstract ideas are not themselves patentable (although a particular application of a law of nature or an abstract idea might be patent-eligible).[14]

- novel.[15]

- nonobvious.[16]

- useful.[17]

- fully disclosed and enabled.[18]

As is entirely typical,[citation needed] the defendant argued that DDR's patents were invalid under all of these sections, but the primary litigation focus was on § 101 and whether DDR's patents were claiming an abstract idea which would not be patentable subject matter.[4]

In Alice, the Supreme Court clarified its two-prong framework, originally set forth in Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc.,[19] for evaluating the patent-eligibility of a claim under § 101. First one must determine whether the claim is directed to a patent-ineligible law of nature, natural phenomenon, or abstract idea. If so, then one determines whether any additional claim elements transform the claim into a patent-eligible application that amounts to significantly more than the ineligible concept itself. Under Alice,[20] Mayo,[19] and Ultramercial,[21] claims are patent-ineligible under § 101 if they are directed to patent-ineligible subject matter (i.e. abstract ideas, laws of nature, and natural phenomena) and do not contain an inventive concept that sufficiently transforms the claim into an application of the underlying idea that restricts the claim to something significantly different from the ineligible subject matter it is directed to. This embodiment must be something more than typical operations performed on a generic computer. Following the Alice decision, several cases invalidated patents covering computer-implemented inventions as ineligible abstract ideas, including Ultramercial. Because the analyses in these decisions are somewhat ambiguous (on, e.g., defining the scope and standard of the term "abstract idea"), many inventors, bloggers, scholars, and patent lawyers have struggled with determining their full implication, especially as they relate to software claims, and some have even questioned the patentability of computer-implemented inventions in general.[22]

Decision

[edit]Judge Chen authored the opinion of the Federal Circuit, joined by Judge Wallach, which invalidated DDR's ‘572 patent as anticipated (overruling the District Court) and affirmed the District Court’s denial of NLG’s renewed motions for JMOL on invalidity and noninfringement of the ‘399 patent.[23] The Federal Circuit Court held that the relevant claims of the ‘399 patent were directed to patent eligible subject matter and that the jury was presented with substantial evidence on which to base its finding that NLG infringed the ‘399 patent.[24] Judge Mayer authored a dissenting opinion, arguing that the ‘399 patent was "long on obfuscation but short on substance[,]" and criticized the invention as "so rudimentary that it borders on the comical." He interpreted Alice to create a "technological arts" test which DDR's claims failed because they were directed toward an entrepreneurial objective (i.e. "retaining control over the attention of the customer") rather than a technological goal.[25]

§ 101 Analysis

[edit]The case is most significant for its discussion of 35 U.S.C. § 101 and the concept of an unpatentable abstract idea as it applies to software and business methods. [citation needed]In this discussion, the Federal Circuit applied the two-step test for patentability set forth in Alice to determine that DDR's '399 patent claims are directed to patent-eligible subject matter. First, it considered whether the claims were directed to a patent-ineligible abstract idea. Judge Chen does not arrive at a clear answer to this inquiry. Instead, he opts to ground his opinion in the more perceptible nature of eligibility should the analysis proceed to step two, without deciding whether that step is actually necessary.[26]

Step 1: Abstract idea?

[edit]As an initial matter, the court must determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent ineligible concept (e.g. an abstract idea).[citation needed] At this step, the court observed that distinguishing between a patentable invention and an abstract idea "can be difficult, as the line separating the two is not always clear."[27] Judge Chen acknowledged that the invention could be characterized as an abstract idea, such as "making two e-commerce web pages look alike," but also noted that the asserted claims of the ‘399 patent "do not recite a mathematical algorithm . . . [n]or do they recite a fundamental economic or longstanding commercial practice."[9] It reviewed several Supreme Court cases useful in identifying claims directed to abstract ideas.[28] However, the Federal Circuit Court never offered a precise definition of an unpatentable "abstract idea" nor did it explicitly decide whether the '399 claims are directed to such ineligible subject matter. [citation needed]Instead, the court concludes that, even stipulating any of the characterizations of the alleged abstract idea put forth by defense counsel and the dissent, the '399 claims still contain an inventive concept sufficient to render them patent-eligible under step two of the Alice analysis.[9]

Step 2: Inventive concept

[edit]In step two, the court must "consider the elements of each claim — both individually and as an ordered combination — to determine whether the additional elements transform the nature of the claim into a patent-eligible application of that abstract idea.[27] This second step is the search for an ‘inventive concept,’ or some element or combination of elements sufficient to ensure that the claim in practice amounts to ‘significantly more’ than a patent on an ineligible concept."[29]

In spite of the business-related nature of the claims (retaining or increasing website traffic) and the fact that they could be implemented on a generic computer, the court highlighted that the claims did not simply take an abstract business method from the pre-internet world and implement it on a computer. Instead, the claims addressed a technological problem "particular to the internet" by implementing a solution specific to that technological environment and different from the manner suggested by routine or conventional use within the field.[9]

The majority opinion characterized the problem as "the ephemeral nature of an Internet 'location' [and] the near-instantaneous transport between these locations made possible by standard communication protocols.[25] The majority distinguished this problem, which they found was "particular to the Internet," from the circumstances inherent in the "store within a store" schemes—in traditional "brick and mortar" warehouse stores with cruise vacation package kiosks, visitors to the kiosk are still inside the warehouse store when making their kiosk purchases.[25] Judge Chen thus found that "the claimed solution is necessarily rooted in computer technology in order to overcome a problem specifically arising in the realm of computer networks."[9]

The DDR court differentiated the claims of the ‘399 patent from those that "merely recite the performance of some business practice known from the pre-Internet world along with the requirement to perform it on the Internet."[citation needed] Instead, the court explained, the claims of patent ‘399 "address the problem of retaining website visitors that, if adhering to the routine, conventional functioning of Internet hyperlink protocol, would be instantly transported away from a host's website after clicking on an advertisement and activating a hyperlink." Because the invention "overrides the routine and conventional sequence of events ordinarily triggered by the click of a hyperlink," it did not employ mere ordinary use of a computer or the Internet. [citation needed]

Further, the court held, the claims included additional features that limit their scope to not preempt every application of any of the abstract ideas suggested by NLG. Viewed individually and as an ordered combination, the DDR court concluded that the claims these aspects of the invention established an "inventive concept" for resolving an Internet-centric problem and were therefore directed to patent-eligible subject matter.[citation needed]

Distinctions from patent-ineligible claims of past cases

[edit]The court found that the ‘399 patent claims were significantly different from the patent-ineligible claims in Alice, Ultramercial, buySAFE, Accenture and Bancorp, in that the ‘399 claims did not "(1) recite a commonplace business method aimed at processing business information, (2) apply a known business process to the particular technological environment of the Internet, or (3) create or alter contractual relations using generic computer functions and conventional network operations."[30]

Unlike other cases recently decided under the Alice framework, the DDR court stated that the ‘399 patent does not "broadly and generically claim use of the Internet to perform an abstract business practice (with insignificant added activity)." [citation needed] Instead, the claims "specify how interactions with the Internet are manipulated to yield a desired result -- a result that overrides the routine and conventional sequence of events ordinarily triggered by the click of a hyperlink." The claimed system changes the normal operation of the Internet so that the visitor is directed to a "hybrid web page that presents product information from the third-party and visual 'look and feel' elements from the host website."[4] Thus, Judge Chen concluded that the claimed invention "is not merely the routine or conventional use of the Internet."[4]

In Ultramercial, Inc. v. Hulu, the court analyzed the eligibility of patent claims directed to a method for distributing copyrighted media products over the Internet where the consumer receives the content, paid for by an advertiser, in exchange for viewing an advertisement.[citation needed] Although the problem solved by the invention arguably was particular to the Internet, the court concluded that the steps of the claims are "an abstraction – an idea, having no particular concrete or tangible form." [citation needed]The court went on to hold that the limitations of the claims "do not transform the abstract idea ... into patent-eligible subject matter because the claims simply instruct the practitioner to implement the abstract idea with routine, conventional activity." The Federal Circuit's DDR decision distinguished itself from Ultramercial by noting:

- "The ’399 patent’s claims are different enough in substance from those in Ultramercial because they do not broadly and generically claim "use of the Internet" to perform an abstract business practice (with insignificant added activity). Unlike the claims in Ultramercial, the claims at issue here specify how interactions with the Internet are manipulated to yield a desired result—a result that overrides the routine and conventional sequence of events ordinarily triggered by the click of a hyperlink… When the limitations of the ’399 patent’s asserted claims are taken together as an ordered combination, the claims recite an invention that is not merely the routine or conventional use of the Internet.

- It is also clear that the claims at issue do not attempt to preempt every application of the idea of increasing sales by making two web pages look the same, or of any other variant suggested by NLG. Rather, they recite a specific way to automate the creation of a composite web page by an "outsource provider" that incorporates elements from multiple sources in order to solve a problem faced by websites on the Internet."[31]

The majority also distinguished the brick-and-mortar analog to the patented invention—in-store kiosks—as "not hav[ing] to account for the ephemeral nature of an Internet ‘location’ or the near-instantaneous transport between these locations made possible by standard Internet communication protocols, which introduces a problem that does not arise in the ‘brick and mortar’ context."[25]

Dissent

[edit]Judge Mayer in his dissent proposed a brick and mortar analog to the claimed invention where an individual shop within a larger store had the same décor as the larger shop to "dupe" shopper to believing he/she was in the larger store. Hence, the claimed invention did not address a unique problem to the internet.[32]

Significance and reception

[edit]Commentary

[edit]Professor Crouch, in the Patently-O blog, commented: "The case is close enough to the line that I expect a strong push for en banc review and certiorari. Although Judge Chen’s analysis is admirable, I cannot see it standing up to Supreme Court review and, the holding here is in dreadful tension with the Federal Circuit’s recent Ultramercial decision."[33]

Gene Quinn, a patent lawyer and blogger at IPWatchdog, doubts that this case can be reconciled with Ultramercial, despite the Federal Court's attempt to distinguish the two. Quinn found the difference between DDR and Ultramercial "thin" and one "that is not at all likely to lead to a repeatable and consistent test that can be applied in a predictable way."[34]

Michael Borella, a patent attorney, said in the Patent Docs blog: "Not only does this case give us another data point of how a computer-implemented invention that incorporates an abstract idea can be patent-eligible (Diamond v. Diehr is the other notable example), but it also provides the first appellate use of the second prong of the Alice test to do so."[35]

District courts

[edit]As one professorial commentator noted, "Because DDR Holdings is the only post-Alice Federal Circuit decision so far to uphold a patent against a § 101 challenge, patentees have been quick to cite it and accused infringers have found ways to distinguish it."[36] Among the district court cases interpreting and applying DDR Holdings are:

- KomBea Corp. v. Noguar L.C., 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 177186 (D. Utah Dec. 23, 2014) – "The patents-in-suit are distinguishable from the patents in DDR Holdings. First, the patents-in-suit are not directed toward solving a new problem, unique to a technological field. Rather, the patents-in-suit are directed toward performing fundamental commercial practices more efficiently. Second, the patents-in-suit are not a new solution to a unique problem; they only employ a combination of sales techniques and basic telemarketing technology to create an efficient system. . . . In this case, the fact that Defendant’s patents-in-suit are directed toward abstract ideas that are more efficiently executed with the use of a generic computer does not make the patents eligible for protection. Therefore, the Court finds that the claims, individually and collectively, do not transform the abstract ideas within the claims into an inventive concept. As such, the patents-in-suit fail to transform the abstract ideas they claim into patent-eligible subject matter."

- MyMedicalRecords, Inc. v. Walgreen Co., 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 176891 (C.D. Cal. Dec. 23, 2014) – "Unlike the claims in DDR these claims are directed to nothing more than the performance of a long-known abstract idea 'from the pre-Internet world' — collecting, accessing, and managing health records in a secure and private manner — on the Internet or using a conventional computer. The patent claims are not 'rooted in computer technology in order to overcome a problem specifically arising in the realm of computer networks' [as in] DDR. Rather, the patent recites an invention that is merely the routine and conventional use of the Internet and computer with no additional specific features."

- Open TV, Inc. v. Apple, Inc., – F. Supp. 2d – (N.D. Cal. Apr. 6, 2015) – "Even construing the claims as Open TV does, the invention claimed by the `799 Patent is not 'necessarily rooted in computer technology in order to overcome a problem specifically arising in the realm of [television] networks.' DDR Holdings, 773 F.3d at 1257. Rather, as noted above, the problem of transmitting confidential information using unsecure communication methods has existed for centuries, long before the advent of interactive television networks. . . . Here, as described more fully above in the Court's analysis of the first prong of the Alice test, the `799 Patent does not claim a solution to a problem that arose uniquely in the context of interactive television networks. Furthermore, the `799 Patent claims recite a method that does not go beyond the 'routine or conventional use' of existing electronic components."

- Messaging Gateway Solns. LLC v. Amdocs, Inc., – F. Supp. 2d – (D. Del. Apr. 15, 2015) – "The Court finds that Claim 20 contains an inventive concept sufficient to render it patent-eligible. Like the claims in DDR Holdings, Claim 20 'is necessarily rooted in computer technology in order to overcome a problem specifically arising in the realm of computer networks.' See id. at 1257. Claim 20 is directed to a problem unique to text-message telecommunication between a mobile device and a computer. The solution it provides is tethered to the technology that created the problem."

- Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. Symantec Corp., 100 F. Supp. 3d 371 (D. Del. 2015), reversed in pertinent part, 838 F.3d 1307 (Fed. Cir. 2016) – "The Federal Circuit in DDR Holdings, 773 F.3d at 1259, held that the 'Internet-centric' claims at issue there were patent eligible. Claim 7 of the '610 patent is 'Internet-centric.' In fact, the key idea of the patent is that virus detection can take place remotely between two entities in a telephone network. This is advantageous because it saves resources on the local caller and calling machines and more efficiently executes virus detection at a centralized location in the telephone network. Claims that 'purport to improve the functioning of the computer itself' or 'effect an improvement in any other technology or technical field' may be patentable under § 101. Alice."

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ DDR Holdings LLC v. Hotels.com, 773 F.3d 1245 (2014).

- ^ Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int'l, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014); Blake Wong, Solving Problems Unique to the Internet May be Patent-Eligible: DDR Holdings, LLC, v. Hotels.com, L.P., Nat'l L. Rev. (Jan. 29, 2015) (online version).

- ^ a b 35 U.S.C. § 101

- ^ a b c d DDR Holdings, 773 F.3d at 1259.

- ^ a b Alice, 134 S. Ct. at 2357.

- ^ a b c d DDR Holdings, 773 F.3d at 1248.

- ^ DDR Holdings, LLC v. Hotels.com, L.P., 954 F. Supp. 2d 509 (E.D. Tex. 2013).

- ^ U.S. patent 7,818,399, 2:30–34.

- ^ a b c d e DDR Holdings, 773 F.3d at 1257.

- ^ See Richard H. Stern, Case-Law Developments After State Street and AT&T (Cont'd): After Alice in the Supreme Court: Down the Rabbit Hole? Or Push-Back? Archived 2015-10-19 at the Wayback Machine, George Washington Law School, Computer Law 484, Cases and Materials, Ch. 8-D (last visited July 22, 2015) (cited hereinafter as GW Computer Law).

- ^ DDR Holdings, 773 F.3d at 1258, 1265.

- ^ GW Computer Law. The diagram of the "store within a store" or "webpage within a webpage" in the text following this note is taken from that source.

- ^ U.S. patent 7,818,399, 4-5.

- ^ Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. 303 (1980); e.g. Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 566 U.S. 66 (2012); Alice, 134 S.Ct. at 2359.

- ^ 35 U.S.C. § 102.

- ^ 35 U.S.C. § 103.

- ^ 35 U.S.C. §§ 101, 112

- ^ 35 U.S.C. § 112.

- ^ a b Mayo, 132 S. Ct. at 1289.

- ^ Alice, 134 S.Ct. at 2359.

- ^ Ultramercial, Inc. v. Hulu, LLC, 772 F.3d 709, 716-17 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

- ^ E.g. Timothy B. Lee, You can’t patent movies or music. So why are there software patents?, Vox Tech. (Sept. 16, 2014) (last visited July 22, 2015); Robert Sachs, The Day the Exception Swallowed the Rule: Is Any Software Patent-Eligible After Ultramercial III? Archived 2015-02-28 at the Wayback Machine, Bilskiblog.com (Dec. 2, 2014) (last visited July 22, 2015). See also Dennis Crouch, Slicing the Bologna: Judge Chen Distinguishes this Business Method from those Found Ineligible in Alice, Bilski, and Ultramercial, PatentlyO Blog (Dec. 8, 2014) (last visited February 23, 2015).

- ^ DDR Holdings, 773 F.3d at 1263.

- ^ DDR Holdings, 773 F.3d at 1261.

- ^ a b c d DDR Holdings, 773 F.3d at 1258.

- ^ DDR Holdings, 773 F.3d at 1256-57.

- ^ a b DDR Holdings, 773 F.3d at 1255.

- ^ DDR Holdings, 773 F.3d at 1256.

- ^ Alice, 134 S. Ct. at 2355.

- ^ Michelle K. Holoubek & Lestin L. Kenton Jr., DDR Holdings—A Beacon Of Hope For Software Patents, Law360.com (Dec. 9, 2014) (last viewed Feb. 28, 2015).

- ^ DDR Holdings, 773 F.3d at 1258-59.

- ^ Ron Laurie, Alice in Blunderland: The Supreme Court's Conflation of Abstractness and Obviousness, IP Watchdog (Dec. 11, 2014) (last visited July 22, 2015); Crouch.

- ^ Crouch.

- ^ Gene Quinn, Federal Circuit Finds Software Patent Claim Patent Eligible (Dec. 5, 2014) (retrieved Feb. 24, 2015).

- ^ Michael Borella,DDR Holdings, LLC v. Hotels.com, L.P. (Fed. Cir. 2014), Patent Docs (Dec. 8, 2014) (Accessed Feb. 28, 2015).

- ^ GW Computer Law.

External links

[edit]- Text of DDR Holdings LLC v. Hotels.com, 773 F.3d 1245 (Fed. Cir. 2014) is available from: CourtListener Google Scholar Justia Leagle