Children of Men

| Children of Men | |

|---|---|

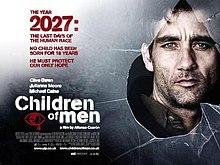

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alfonso Cuarón |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Children of Men by P. D. James |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Emmanuel Lubezki |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | John Tavener |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 109 minutes[2] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $76 million[1] |

| Box office | $70.5 million[1] |

Children of Men is a 2006 dystopian action thriller film[4][5][6][7] directed and co-written by Alfonso Cuarón. The screenplay, based on P. D. James' 1992 novel The Children of Men, was credited to five writers, with Clive Owen making uncredited contributions. The film is set in 2027 when two decades of human infertility have left society on the brink of collapse. Asylum seekers seek sanctuary in the United Kingdom, where they are subjected to detention and deportation by the government. Owen plays civil servant Theo Faron, who tries to help refugee Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey) escape the chaos. Children of Men also stars Julianne Moore, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Pam Ferris, Charlie Hunnam, and Michael Caine.

The film was released by Universal Pictures on 22 September 2006, in the UK and on 25 December in the US. Despite the limited release and lack of any clear marketing strategy during awards season by the film's distributor,[8][9][10] Children of Men received critical acclaim and was recognised for its achievements in screenwriting, cinematography, art direction, and innovative single-shot action sequences. It was nominated for three Academy Awards: Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Cinematography, and Best Film Editing. It was also nominated for three BAFTA Awards, winning Best Cinematography and Best Production Design, and for three Saturn Awards, winning Best Science Fiction Film. In 2016, it was voted 13th among 100 films considered the best of the 21st century by 117 film critics from around the world.

Plot

[edit]In 2027, eighteen years after human activities have caused widespread ecocide, total human infertility, war, and global depression threaten the collapse of human civilizations.[11] The United Kingdom is one of the few remaining nations with a functioning government and has become a police state in which immigrants are arrested and either imprisoned or executed.

Theo Faron, a former activist turned cynical bureaucrat, is kidnapped by the Fishes, a militant immigrant-rights group led by Theo's estranged wife, Julian Taylor; the pair separated after their son's death during a 2008 flu pandemic. Julian offers Theo money to acquire transit papers for a young refugee woman named Kee. Theo obtains the documents from his cousin, a government minister, and agrees to escort Kee in exchange for a larger sum of money. Luke, a Fishes leader, drives Theo, Kee, Julian, and former midwife Miriam towards Canterbury, but an armed gang ambushes them and kills Julian. Two police officers later stop their car; Luke kills them, and the group hides Julian's body before heading to a safe house.

Kee reveals to Theo that she is pregnant, making her the only known pregnant woman in the world. Julian had intended to take her to the Human Project, a scientific research group in the Azores dedicated to curing humanity's infertility, which Theo believes does not exist. Luke becomes the new leader of the Fishes. That night, Theo eavesdrops on a discussion and learns that the Fishes orchestrated Julian's death so that Luke could become their leader and that they intend to kill him and use Kee's baby as a political tool. Theo wakes Kee and Miriam, and they escape to the secluded hideaway of Theo's reclusive, aging hippie friend Jasper Palmer, a former political cartoonist whose wife Janice was tortured into catatonia by the British government for her activism.

The group plans to reach the Human Project ship, the Tomorrow, scheduled to arrive offshore at Bexhill, a notorious immigrant detention centre. Jasper plans to use Syd, an immigration officer to whom Jasper sells cannabis, to smuggle them into Bexhill as refugees, from where they can take a rowing boat to rendezvous with the Tomorrow. The next day, the Fishes discover Jasper's house, forcing the group to flee. Jasper stays behind to stall them and is murdered by Luke as Theo watches. Theo, Kee, and Miriam meet with Syd, who helps them board a bus to the camp. When Kee begins experiencing contractions, Miriam distracts a guard by feigning religious mania and is taken away.

Inside the camp, Theo and Kee meet a Romani woman, Marichka, who provides a room where Kee gives birth to a baby girl. The next day, Syd tells Theo and Kee that war has broken out between the British military and the refugees and that the Fishes have infiltrated the camp; he then reveals that Theo and Kee have a bounty on their heads and attempts to capture them. Theo subdues Syd with Marichka's help; they escape but are ambushed by the Fishes, who capture Kee and the baby. Theo tracks them to an apartment building that is under heavy fire. Theo confronts Luke, who is killed in an explosion, and Theo escorts Kee and the baby out. Awed by the baby, the British soldiers and Fishes temporarily stop fighting and allow the trio to leave. Marichka leads them to the boat but stays behind as they depart.

As British fighter jets conduct airstrikes on Bexhill, Theo and Kee row to the rendezvous point in heavy fog. Theo reveals that he was shot and wounded by Luke earlier; he teaches Kee how to burp her baby, and she tells him she will name the baby girl Dylan, after Theo's and Julian's lost son. Theo smiles weakly, then loses consciousness as the Tomorrow approaches. As the screen cuts to black, children's laughter is heard.

Cast

[edit]

- Clive Owen as Thelonius "Theo" Faron, a former activist who was devastated when his child died during a flu pandemic.[12] Theo is the "archetypal everyman" who reluctantly becomes a saviour.[13][14] Cast in April 2005,[15] Owen spent several weeks collaborating with Cuarón and Sexton on his role. Impressed by Owen's creative insights, Cuarón and Sexton brought him on board as a writer.[16] "Clive was a big help", Cuarón told Variety. "I would send a group of scenes to him, and then I would hear his feedback and instincts."[17]

- Clare-Hope Ashitey as Kee, an asylum seeker and the first pregnant woman in eighteen years. She did not appear in the book, and was written into the film based on Cuarón's interest in the recent single-origin hypothesis of human origins and the status of dispossessed people:[18] "The fact that this child will be the child of an African woman has to do with the fact that humanity started in Africa. We're putting the future of humanity in the hands of the dispossessed and creating a new humanity to spring out of that."[19]

- Julianne Moore as Julian Taylor. For Julian, Cuarón wanted an actress who had the "credibility of leadership, intelligence, [and] independence".[16] Moore was cast in June 2005, initially to play the first woman to become pregnant in 20 years.[20] "She is just so much fun to work with", Cuarón told Cinematical. "She is just pulling the rug out from under your feet all the time. You don't know where to stand, because she is going to make fun of you."[16]

- Michael Caine as Jasper Palmer, Theo's friend. Caine based Jasper on his experiences with his friend John Lennon[16] – the first time he had portrayed a character who would fart or smoke cannabis.[21] Cuarón explains, "Once he had the clothes and so on and stepped in front of the mirror to look at himself, his body language started changing. Michael loved it. He believed he was this guy".[21] Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune notices an apparent homage to Schwartz in Orson Welles' film noir Touch of Evil (1958). Jasper calls Theo "amigo"—just as Schwartz referred to Ramon Miguel Vargas.[22] Jasper's cartoons, seen in his house, were provided by Steve Bell.[23]

- Pam Ferris as Miriam, a midwife taking care of Kee.

- Chiwetel Ejiofor as Luke

- Charlie Hunnam as Patric

- Peter Mullan as Syd

- Danny Huston as Nigel, Theo's cousin and a high-ranking government official. Nigel runs a Ministry of Arts program "Ark of the Arts", which "rescues" works of art such as Michelangelo's David, Pablo Picasso's Guernica, and Banksy's Kissing Coppers.

- Paul Sharma as Ian

- Jacek Koman as Tomasz

- Juan Gabriel Yacuzzi as 'Baby' Diego, the world's youngest surviving human, born shortly before the global infertility incident.

- Ed Westwick as Alex, Nigel's son

Production

[edit]

The option for the book was acquired by Beacon Pictures in 1997.[24] The adaptation of the P. D. James novel was originally written by Paul Chart, and later rewritten by Mark Fergus and Hawk Ostby. The studio brought director Alfonso Cuarón on board in 2001.[25] Cuarón and screenwriter Timothy J. Sexton began rewriting the script after the director completed Y tu mamá también. Afraid he would "start second guessing things",[21] Cuarón chose not to read P. D. James' novel, opting to have Sexton read the book while Cuarón himself read an abridged version.[16][26] Cuarón did not immediately begin production, instead directing Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. During this period, David Arata rewrote the screenplay and delivered the draft which secured Clive Owen and sent the film into pre-production. The director's work experience in the United Kingdom exposed him to the "social dynamics of the British psyche", giving him insight into the depiction of "British reality".[27] Cuarón used the film The Battle of Algiers as a model for social reconstruction in preparation for production, presenting the film to Clive Owen as an example of his vision for Children of Men. In order to create a philosophical and social framework for the film, the director read literature by Slavoj Žižek, as well as similar works.[28] The 1927 film Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans was also influential.[29]

Location

[edit]A Clockwork Orange was one of the inspirations for the futuristic, yet battered patina of 2027 London.[29] Children of Men was the second film Cuarón made in London, with the director portraying the city using single, wide shots.[30] While Cuarón was preparing the film, the London bombings occurred, but the director did not consider moving the production. "It would have been impossible to shoot anywhere but London, because of the very obvious way the locations were incorporated into the film", Cuarón told Variety. "For example, the shot of Fleet Street looking towards St. Paul's would have been impossible to shoot anywhere else."[30] Due to these circumstances, the opening terrorist attack scene on Fleet Street was shot a month and a half after the London bombing.[28]

Cuarón chose to shoot some scenes in East London, a location he considered "a place without glamour". The set locations were dressed to make them appear even more run-down; Cuarón says he told the crew "'Let's make it more Mexican'. In other words, we'd look at a location and then say: yes, but in Mexico there would be this and this. It was about making the place look run-down. It was about poverty."[28] He also made use of London's most popular sites, shooting in locations like Trafalgar Square and Battersea Power Station. The power station scene (whose conversion into an art archive is a reference to the Tate Modern), has been compared to Antonioni's Red Desert.[31] Cuarón added a pig balloon to the scene as homage to Pink Floyd's Animals.[32] Other art works visible in this scene include Michelangelo's David,[33] Picasso's Guernica,[34] and Banksy's Kissing Coppers.[35] London visual effects companies Double Negative and Framestore worked directly with Cuarón from script to post production, developing effects and creating "environments and shots that wouldn't otherwise be possible".[30]

The Historic Dockyard in Chatham was used to film the scene in the empty activist safehouse.[36]

The Shard tower was digitally added to London's skyline based on early architectural drawings as when the film was made the skyscraper had not yet been built but would have been by the time of the film's setting.[37]

Style and design

[edit]"In most sci-fi epics, special effects substitute for story. Here they seamlessly advance it", observes Colin Covert of Star Tribune.[38] Billboards were designed to balance a contemporary and futuristic appearance as well as easily visualizing what else was occurring in the rest of the world at the time, and cars were made to resemble modern ones at first glance, although a closer look made them seem unfamiliar.[39] Cuarón informed the art department that the film was the "anti-Blade Runner",[40] rejecting technologically advanced proposals and downplaying the science fiction elements of the 2027 setting. The director focused on images reflecting the contemporary period.[41][42]

References to the 2012 Summer Olympics were included in the film as London had been announced as the host city in July 2005, a few months before filming took place.[43]

Single-shot sequences

[edit]Children of Men used several lengthy single-shot sequences in which extremely complex actions take place. The longest of these is a shot in which Kee gives birth (3m,19s); an ambush on a country road (4m,7s); and a scene in which Theo is captured by the Fishes, escapes, and runs down a street and through a building in the middle of a raging battle (6m,18s).[44] These sequences were extremely difficult to film, although the effect of continuity is sometimes an illusion, aided by computer-generated imagery (CGI) effects and the use of 'seamless cuts' to enhance the long takes.[45][46]

Cuarón had experimented with long takes in Great Expectations, Y tu mamá también, and Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. His style is influenced by the Swiss film Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000, one of his favourites. He said "I was studying cinema when I first saw [Jonah], and interested in the French New Wave. Jonah was so unflashy compared with those films. The camera keeps a certain distance and there are relatively few close-ups. It's elegant and flowing, constantly tracking, but very slowly and not calling attention to itself."[47]

The creation of the single-shot sequences was a challenging, time-consuming process that sparked concerns from the studio. It took fourteen days to prepare for the single shot in which Clive Owen's character searches a building under attack and five hours every time they wanted to reshoot it. In the middle of one shot, blood splattered onto the lens, and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki convinced the director to leave it in. According to Owen, "Right in the thick of it are me and the camera operator because we're doing this very complicated, very specific dance which, when we come to shoot, we have to make feel completely random."[48]

Cuarón's initial idea for maintaining continuity during the roadside ambush scene was dismissed by production experts as an "impossible shot to do". Fresh from the visual effects-laden Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Cuarón suggested using computer-generated imagery to film the scene. Lubezki refused to allow it, reminding the director that they had intended to make a film akin to a "raw documentary". Instead, a special camera rig invented by Gary Thieltges of Doggicam Systems was employed, allowing Cuarón to develop the scene as one extended shot.[22][49] A vehicle was modified to enable seats to tilt and lower actors out of the way of the camera, and the windshield was designed to tilt out of the way to allow camera movement in and out through the front windscreen. A crew of four, including the director of photography and camera operator, rode on the roof.[50]

However, the commonly reported statement that the action scenes are continuous shots[51] is not entirely true. Visual effects supervisor Frazer Churchill explains that the effects team had to "combine several takes to create impossibly long shots", where their job was to "create the illusion of a continuous camera move". Once the team was able to create a "seamless blend", they would move on to the next shot. These techniques were important for three continuous shots: the coffee shop explosion in the opening shot, the car ambush, and the battlefield scene. The coffee shop scene was composed of "two different takes shot over two consecutive days"; the car ambush was shot in "six sections and at four different locations over one week and required five seamless digital transitions"; and the battlefield scene "was captured in five separate takes over two locations". Churchill and the Double Negative team created over 160 of these types of effects for the film.[52] In an interview with Variety, Cuarón acknowledged this nature of the "single-shot" action sequences: "Maybe I'm spilling a big secret, but sometimes it's more than what it looks like. The important thing is how you blend everything and how you keep the perception of a fluid choreography through all of these different pieces."[17]

Tim Webber of VFX house Framestore CFC was responsible for the three-and-a-half-minute single take of Kee giving birth, helping to choreograph and create the CG effects of the childbirth.[30] Cuarón had originally intended to use an animatronic baby as Kee's child with the exception of the childbirth scene. In the end, two takes were shot, with the second take concealing Clare-Hope Ashitey's legs, replacing them with prosthetic legs. Cuarón was pleased with the results of the effect, and returned to previous shots of the baby in animatronic form, replacing them with Framestore's computer-generated baby.[45]

Sound

[edit]Cuarón used a combination of rock, pop, electronic music, hip-hop and classical music for the film's soundtrack.[53] Ambient sounds of traffic, barking dogs, and advertisements follow the character of Theo through London, East Sussex and Kent, producing what Los Angeles Times writer Kevin Crust called an "urban audio rumble".[53] Crust considered that the music comments indirectly on the barren world of Children of Men: Deep Purple's version of "Hush" playing from Jasper's car radio becomes a "sly lullaby for a world without babies" while King Crimson's "The Court of the Crimson King" make a similar allusion with their lyrics, "three lullabies in an ancient tongue".[53]

Amongst a genre-spanning selection of electronic music, a remix of Aphex Twin's "Omgyjya Switch 7", which includes the 'Male Thijs Loud Scream' audio sample by Thanvannispen[54] can be heard during an early scene in Jasper's house. During a conversation between the two men, Radiohead's "Life in a Glasshouse" plays in the background. A number of dubstep tracks, including "Anti-War Dub" by Digital Mystikz, as well as tracks by Kode9 & The Space Ape, Pinch and Pressure are also featured.[55]

For the Bexhill scenes during the film's second half, Cuarón makes use of silence and cacophonous sound effects such as the firing of automatic weapons and loudspeakers directing the movement of refugees.[53] Classical music by George Frideric Handel, Gustav Mahler, and Krzysztof Penderecki's "Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima" complements the chaos of the refugee camp.[53] Throughout the film, John Tavener's Fragments of a Prayer is used as a spiritual motif.[53]

Themes

[edit]Hope and faith

[edit]Children of Men explores the themes of hope and faith[56] in the face of overwhelming futility and despair.[57][29] The film's source, P. D. James' novel The Children of Men (1992), describes what happens when society is unable to reproduce, using male infertility to explain this problem.[58][59] In the novel, it is made clear that hope depends on future generations. James writes "It was reasonable to struggle, to suffer, perhaps even to die, for a more just, a more compassionate society, but not in a world with no future where, all too soon, the very words 'justice', 'compassion', 'society’, 'struggle', 'evil', would be unheard echoes on an empty air."[60]

The film does not explain the cause of the infertility, although environmental destruction and divine punishment are considered.[29][61][62] Cuarón has attributed this unanswered question (and others in the film) to his dislike for the purely expository film: "There's a kind of cinema I detest, which is a cinema that is about exposition and explanations ... It's become now what I call a medium for lazy readers ... Cinema is a hostage of narrative. And I'm very good at narrative as a hostage of cinema."[63] Cuarón's disdain for back-story and exposition led him to use the concept of infertility as a "metaphor for the fading sense of hope".[63][61] The "almost mythical" Human Project is turned into a "metaphor for the possibility of the evolution of the human spirit, the evolution of human understanding".[64] Cuarón believed that explaining things such as the cause of the infertility and the Human Project would create a "pure science-fiction movie", removing focus from the story as a metaphor for hope.[65][61] Without dictating how the audience should feel by the end of the film, Cuarón encourages viewers to come to their own conclusions about the sense of hope depicted in the final scenes: "We wanted the end to be a glimpse of a possibility of hope, for the audience to invest their own sense of hope into that ending. So if you're a hopeful person you'll see a lot of hope, and if you're a bleak person you'll see a complete hopelessness at the end."[26]

Religion

[edit]Richard Blake, writing for Catholic magazine America, suggested that like Virgil's Aeneid, Dante's The Divine Comedy, and Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales, the crux of the journey in Children of Men lies in what is uncovered along the path rather than the terminus itself.[33] Ethan Alter, reviewing the film for Film Journal International, describes Theo's heroic journey to the coast as mirroring his personal quest for "self-awareness",[66] a journey that takes him from "despair to hope."[67]

According to Cuarón, the title of P. D. James' book (The Children of Men) is an allegory derived from a passage of scripture in the Bible.[68] (Psalm 90 (89):3 of the King James Version: "Thou turnest man to destruction; and sayest, Return, ye children of men") James refers to her story as a "Christian fable"[58] while Cuarón describes it as "almost like a look at Christianity": "I didn't want to shy away from the spiritual archetypes", Cuarón told Filmmaker Magazine. "But I wasn't interested in dealing with dogma."[26]

Ms. James's nativity story is, in Mr. Cuarón's version, set against the image of a prisoner in an orange smock with a black bag on his head, arms stretched out as if on a cross.

This divergence from the original was criticised by some, including Anthony Sacramone of First Things, who called the film "an act of vandalism", noting the irony of how Cuarón had removed religion from P.D. James' fable, in which morally sterile nihilism is overcome by Christianity.[70]

The film has been noted for its use of Christian symbolism; for example, British terrorists named "Fishes" protect the rights of refugees.[71] Opening on Christmas Day in the United States, critics compared the characters of Theo and Kee with Joseph and Mary,[72] calling the film a "modern-day Nativity story".[73] Kee's pregnancy is revealed to Theo in a barn, alluding to the manger of the Nativity scene; when Theo asks Kee who the father of the baby is she jokingly states she is a virgin; and when other characters discover Kee and her baby, they respond with "Jesus Christ" or the sign of the cross.[74]

To highlight these spiritual themes, Cuarón commissioned a 15-minute piece by British composer John Tavener, a member of the Eastern Orthodox Church whose work resonates with the themes of "motherhood, birth, rebirth, and redemption in the eyes of God". Calling his score a "musical and spiritual reaction to Alfonso's film", snippets of Tavener's "Fragments of a Prayer" contain lyrics in Latin, German, and Sanskrit sung by mezzo-soprano Sarah Connolly. Words like "mata" (mother), "pahi mam" (protect me), "avatara" (saviour), and "alleluia" appear throughout the film.[75][76]

In the closing credits, the Sanskrit words "Shantih Shantih Shantih" appear as end titles.[77][78] Writer and film critic Laura Eldred of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill observes that Children of Men is "full of tidbits that call out to the educated viewer". During a visit to his house by Theo and Kee, Jasper says "Shanti, shanti, shanti". Eldred notes that the "shanti" used in the film is also found at the end of an Upanishad and in the final line of T. S. Eliot's poem The Waste Land, a work Eldred describes as "devoted to contemplating a world emptied of fertility: a world on its last, teetering legs". "Shanti" is also a common beginning and ending to all Hindu prayers, and means "peace", referencing the invocation of divine intervention and rebirth through an end to violence.[79]

Contemporary references

[edit]Children of Men takes an unconventional approach to the modern action film, using a documentary, newsreel style.[80] Film critics Michael Rowin, Jason Guerrasio and Ethan Alter observe the film's underlying touchstone of immigration.

For Alter and other critics, the structural support and impetus for the contemporary references rests upon the visual nature of the film's exposition, occurring in the form of imagery as opposed to conventional dialogue.[66] Other popular images appear, such as a sign over the refugee camp reading "Homeland Security".[81] The similarity between the hellish, cinéma vérité stylised battle scenes of the film and current news and documentary coverage of the Iraq War, is noted by film critic Manohla Dargis, describing Cuarón's fictional landscapes as "war zones of extraordinary plausibility".[82]

In the film, refugees are "hunted down like cockroaches", rounded up and put into roofless cages open to the elements and camps, and even shot, leading film critics like Chris Smith and Claudia Puig to observe symbolic "overtones" and images of the Holocaust.[57][83] This is reinforced in the scene where an elderly refugee woman speaking German is seen detained in a cage,[35] and in the scene where British government agents strip and assault refugees; the song "Arbeit Macht Frei" by The Libertines, from Arbeit macht frei, plays in the background.[84] "The visual allusions to the Nazi round-ups are unnerving", writes Richard A. Blake. "It shows what people can become when the government orchestrates their fears for its own advantage."[33]

Cuarón explains how he uses imagery in his fictional and futuristic events to allude to real, contemporary or historical incidents and beliefs,

They exit the Russian apartments, and the next shot you see is this woman wailing, holding the body of her son in her arms. This was a reference to a real photograph of a woman holding the body of her son in the Balkans, crying with the corpse of her son. It's very obvious that when the photographer captured that photograph, he was referencing La Pietà, the Michelangelo sculpture of Mary holding the corpse of Jesus. So: We have a reference to something that really happened, in the Balkans, which is itself a reference to the Michelangelo sculpture. At the same time, we use the sculpture of David early on, which is also by Michelangelo, and we have of course the whole reference to the Nativity. And so everything was referencing and cross-referencing, as much as we could.[16]

Academic analysis

[edit]Several academics have thoroughly examined the themes of the film, with a primary focus on Alfonso Cuarón's creation of a dystopian landscape. One prominent aspect explored is the treatment of refugees, illustrating the regulation of life and the authoritarian tendencies mirrored in the extreme policies of the British government depicted in the film.[85] Additionally, Marcus O'Donnell, a researcher, has characterized the film's political realism as a form of "visionary realism," encompassing various apocalyptic events rather than a singular one.[86] Moreover, the film delves into the notion of political protection juxtaposed with physical life, particularly evident in its exploration of the status of the unborn child. Kee's body serves as the battleground for these conflicting forces, offering a critique of migration politics while simultaneously idealizing the future child.[87] In the extra features on the film’s 2007 DVD release, Slavoj Žižek claims, “I think that the film gives the best diagnosis of ideological despair of late capitalism, of a society without history.” [88]

Release

[edit]Box office

[edit]Children of Men had its world premiere at the 63rd Venice International Film Festival on 3 September 2006.[89] On 22 September 2006, the film debuted at number 1 in the United Kingdom with $2.4 million in 368 screens.[90] It debuted in a limited release of 16 theaters in the United States on 22 December 2006, expanding to more than 1,200 theaters on 5 January 2007.[91] As of 6 February 2008[update], Children of Men had grossed $69,612,678 worldwide, with $35,552,383 of the revenue generated in the United States.[92]

Home media

[edit]The HD-DVD and DVD were released in Europe on 15 January 2007[93] and in the United States on 27 March 2007. Extras include a half-hour documentary by director Alfonso Cuarón, entitled The Possibility of Hope (2007), which explores the intersection between the film's themes and reality with a critical analysis by eminent scholars: the Slovenian sociologist and philosopher Slavoj Žižek, anti-globalization activist Naomi Klein, environmentalist futurist James Lovelock, sociologist Saskia Sassen, human geographer Fabrizio Eva, cultural theorist Tzvetan Todorov, and philosopher and economist John N. Gray. "Under Attack" features a demonstration of the innovative techniques required for the car chase and battle scenes; in "Theo & Julian", Clive Owen and Julianne Moore discuss their characters; "Futuristic Design" opens the door on the production design and look of the film; "Visual Effects" shows how the digital baby was created. Deleted scenes are included.[94] The film was released on Blu-ray Disc in the United States on 26 May 2009.[95]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]Children of Men received critical acclaim; on the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film received a 92% approval rating based on 252 reviews from critics, with an average rating of 8.10/10. The site's critical consensus states: "Children of Men works on every level: as a violent chase thriller, a fantastical cautionary tale, and a sophisticated human drama about societies struggling to live."[96] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 84 out of 100, based on 38 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[97] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade "B−" on an A+ to F scale.[98]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four stars out of four, writing, "Cuarón fulfills the promise of futuristic fiction; characters do not wear strange costumes or visit the moon, and the cities are not plastic hallucinations, but look just like today, except tired and shabby. Here is certainly a world ending not with a bang but a whimper, and the film serves as a cautionary warning."[99] Dana Stevens of Slate called it "the herald of another blessed event: the arrival of a great director by the name of Alfonso Cuarón". Stevens hailed the film's extended car chase and battle scenes as "two of the most virtuoso single-shot chase sequences I've ever seen".[73] Manohla Dargis of The New York Times called the film a "superbly directed political thriller", raining accolades on the long chase scenes.[82] "Easily one of the best films of the year" said Ethan Alter of Film Journal International, with scenes that "dazzle you with their technical complexity and visual virtuosity".[66] Jonathan Romney of The Independent praised the accuracy of Cuarón's portrait of the United Kingdom, but he criticized some of the film's futuristic scenes as "run-of-the-mill future fantasy".[35] Film Comment's critics' poll of the best films of 2006 ranked the film number 19, while the 2006 readers' poll ranked it number two.[100] On their list of the best movies of 2006, The A.V. Club, the San Francisco Chronicle, Slate, and The Washington Post placed the film at number one.[101] Entertainment Weekly ranked the film seventh on its end-of-the-decade top 10 list, saying, "Alfonso Cuarón's dystopian 2006 film reminded us that adrenaline-juicing action sequences can work best when the future looks just as grimy as today".[102]

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone ranked it number two on his list of best films of the decade, writing:

I thought director Alfonso Cuarón's film of P.D. James' futuristic political-fable novel was good when it opened in 2006. After repeated viewings, I know Children of Men is indisputably great ... No movie this decade was more redolent of sorrowful beauty and exhilarating action. You don't just watch the car ambush scene (pure camera wizardry)—you live inside it. That's Cuarón's magic: He makes you believe."[103]

According to Metacritic's analysis of the films most often noted on the best-of-the-decade lists, Children of Men is the 11th greatest film of the 2000s.[104]

In the book 501 Must-See Movies, Rob Hill lauds the movie for its dystopian portrayal of the future and its adept exploration of contemporary issues. Hill highlights the film's societal stagnation and the magnetizing effect of Britain on immigrants and terrorists, emphasizing the director's intelligence in weaving speculative narratives with real-world reflections. He applauds Cuarón's skill in creating a cinematic mirror that resonates with audiences by addressing pressing political and social concerns, all within a compelling dystopian framework.[105]

In the wake of the European migrant crisis of 2015, the British withdrawal from the European Union of the late 2010s, Donald Trump's presidency 2017-2021, and the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, all of which involved divisive debates about immigration and increasing border enforcement, several commentators reappraised the film's importance, with some calling it "prescient".[a]

Top 10 lists

[edit]The film appeared on many critics' top 10 lists as one of the best films of 2006:[101]

- 1st – Ann Hornaday, The Washington Post

- 1st – Keith Phipps, The A.V. Club

- 1st – Peter Hartlaub, San Francisco Chronicle

- 1st – Tasha Robinson, The A.V. Club

- 2nd (of the decade) – Peter Travers, Rolling Stone

- 2nd – Ray Bennett, The Hollywood Reporter

- 2nd – Scott Tobias, The A.V. Club

- 3rd – Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times

- 4th – Kevin Crust, Los Angeles Times

- 4th – Wesley Morris, The Boston Globe

- 5th – Rene Rodriguez, The Miami Herald

- 6th – Manohla Dargis, The New York Times

- 7th – Empire

- 7th – Kirk Honeycutt, The Hollywood Reporter

- 7th – Ty Burr, The Boston Globe

- 8th – Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times (tied with Pan's Labyrinth)

- 8th – Scott Foundas, LA Weekly (tied with L'Enfant)

- 8th – Scott Foundas, The Village Voice

- Unordered – Dana Stevens, Slate

- Unordered – Liam Lacey and Rick Groen, The Globe and Mail

- Unordered – Peter Rainer, The Christian Science Monitor

- Unordered – Mark Kermode, BBC Radio 5 Live[citation needed]

In 2012, director Marc Webb included the film on his list of Top 10 Greatest Films when asked by Sight & Sound for his votes for the BFI The Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time.[117] In 2015, the film was named number one on an all-time Top 10 Movies list by the blog Pop Culture Philosopher.[118] In 2016, it was voted 13th among 100 films considered the best of the 21st century by 117 film critics from around the world.[119] In 2017, Rolling Stone magazine ranked Children of Men as the best Sci-fi film of the 21st century.[120] In 2023, Time listed the film as one of the best 100 movies from the past 10 decades.[121]

Accolades

[edit]P. D. James was reported to be pleased with the film,[122] and the screenwriters of Children of Men were awarded the 19th annual USC Scripter Award for the screen adaptation of the novel.[123]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Children of Men (2006)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ "CHILDREN OF MEN (15)". Universal Studios. British Board of Film Classification. 15 September 2006. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ "Children of Men (2006)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 20 February 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "Children of Men (2006) - Alfonso Cuarón". AllMovie.

- ^ "AFI Catalog - Children of Men". American Film Institute.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (22 September 2006). "Children of Men review – explosively violent future-nightmare thriller". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 November 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ "Children of Men". George Eastman Museum. Archived from the original on 17 July 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ Hoberman, J. (12 December 2006). "Don't Believe the (Lack of) Hype". The Village Voice. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ Dalton, Stephen (18 February 2019). "Children of Men: Why Alfonso Cuarón's anti-Blade Runner looks more relevant than ever". BFI.org.uk. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ Riesman, Abraham (26 December 2016). "Future Shock". Vulture.com. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ Valls Oyarzun, Eduardo; Gualberto Valverde, Rebeca; Malla García, Noelia; Colom Jiménez, María; Cordero Sánchez, Rebeca, eds. (2020). "17: Ecocritical Archaelogies of Global Ecocide in Twenty-First-Centurty Post-Apocalyptic Films". Avenging nature: the role of nature in modern and contemporary art and literature. Ecocritical theory and practice. Lanham Boulder NewYork London: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-7936-2144-3.

- ^ Vineberg, Steve (6 February 2007). "Rumors of a birth". The Christian Century. Vol. 124, no. 3.

- ^ Meyer, Carla (3 January 2007). "Children of Men". Sacramento Bee.

- ^ Williamson, Kevin (3 January 2007). "Man of action". Calgary Sun. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Snyder, Gabriel (27 April 2005). "Owen having U's children". Variety. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Voynar, Kim (25 December 2006). "Interview: Children of Men Director Alfonso Cuarón". Moviefone. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2007.

- ^ a b Debruge, Peter (19 February 2007). "Editors cut us in on tricky sequences". Variety.

- ^ Wagner, Annie (28 December 2006). "Politics, Bible Stories and Hope. An Interview with Alfonso Cuarón". The Stranger. Archived from the original on 7 November 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ Hennerson, Evan (19 December 2006). "Brave new world. Clive Owen embarks on a mission to ensure humanity's survival". Los Angeles Daily News. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 26 February 2007.

- ^ Snyder, Gabriel (15 June 2005). "Moore makes way to U's Children". Variety. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

Moore's character is the first woman to become pregnant in nearly 20 years. Owen is enlisted to protect her after the death of the Earth's youngest person, age 18.

- ^ a b c "Interview: Alfonso Cuaron". Moviehole. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ^ a b Phillips, Michael (24 December 2006). "Children of Men director thrives on collaboration". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ "CHILDREN OF MEN". belltoons.co.uk. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "Beacon finally snares 'Men'". Variety. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (5 October 2001). "Helmer Raises Children". Daily Variety.

- ^ a b c Guerrasio, Jason (22 December 2006). "A New Humanity". Filmmaker Magazine. Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 23 January 2007.

- ^ Douglas, Edward (8 December 2006). "Exclusive: Filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón". ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on 14 December 2006. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ a b c "Children of Men feature". Time Out. 21 September 2006. Archived from the original on 16 February 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ a b c d Wells, Jeffrey (1 November 2006). "Quotations from Interview with Alfonso Cuarón". Hollywood Elsewhere. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 23 January 2007.

- ^ a b c d Barraclough, Leo (18 September 2006). "Nightmare on the Thames". Variety.

- ^ Pols, Mary F. (25 December 2006). "A haunting view of the end". Contra Costa Times.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Faraci, Devin (4 January 2007). "Exclusive Interview: Alfonso Cuaron (Children of Men)". Chud.com. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ a b c Blake, Richard A. (5 February 2007). "What If...?". America.

- ^ French, Philip (24 September 2006). "Film Review Children of Men". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ a b c Romney, Jonathan (January–February 2007). "Green and Pleasant Land". Film Comment. pp. 32–35.

- ^ Kent Film Office (4 February 2006). "Kent Film Office Children of Men Film Focus".

- ^ Sampson, Mike (1 August 2012). "How a 2006 Movie Included the 2012 London Olympics". ScreenCrush. Archived from the original on 8 June 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ Covert, Colin (5 January 2007). "Movie review: Future shock in Children of Men". Star Tribune.

- ^ Roberts, Sheila (19 December 2006). "Alfonso Cuarón Interview, Director of Children of Men". MoviesOnline.ca. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ "The Connecting of Heartbeats". Nashville Scene. 1 January 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 15 February 2007.

- ^ Briggs, Caroline (20 September 2006). "Movie imagines world gone wrong". BBC. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ Horn, John (19 December 2006). "There's no place like hell for the holidays". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ Sampson, Mike (1 August 2012). "How a 2006 Movie Included the 2012 London Olympics". ScreenCrush.

- ^ Miller, Neil (29 April 2012). "Scenes We Love: Explore Alfonso Cuaron's Addiction to Single Takes in 'Children of Men'". Film School Rejects. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Framestore CFC Delivers Children of Men". VFXWorld Magazine. 16 October 2006. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ Benjamin, B (6 April 2022). "Children of Men: Humanity's Last Hope". American Cinematographer. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Johnston, Sheila (30 September 2006). "Film-makers on film: Alfonso Cuarón". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ Sutherland, Claire (19 October 2006). "Clive's happy with career". Herald Sun. Archived from the original on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ "Two Axis Dolly". Doggicam Systems. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 24 January 2007.

- ^ mseymour7 (4 January 2007). "Children of Men – Hard Core Seamless vfx". fxguide. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Murray, Steve (29 December 2006). "Anatomy of a Scene". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on 22 January 2007. Retrieved 24 January 2007.

- ^ Bielik, Alain (27 December 2006). "Children of Men: Invisible VFX for a Future in Decay". VFXWorld Magazine. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Crust, Kevin (7 January 2007). "Critic's Notebook; Sounds to match to the Children of Men vision". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ "9432 thanvannispen male-thijs-loud-scream by Linus Carl Norlen". Soundcloud.com. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ^ Reynolds, Simon. "Reasons to Be Cheerful (Just Three)". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 22 June 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- ^ "Cuaron Mulls SF Film". Sci Fi Wire. 27 May 2004. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 4 February 2007.

- ^ a b Puig, Claudia (21 December 2006). "Children of Men sends stark message". USA Today. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- ^ a b "You ask the questions: P. D. James". The Independent. 14 March 2001. Retrieved 16 January 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Seshadri, B. (1 February 1995). "Male infertility and world population". Contemporary Review. Archived from the original on 14 May 2007. Retrieved 23 January 2007.

- ^ Bowman, James (2007). "Our Childless Dystopia". The New Atlantis (15): 107–110. Archived from the original on 26 May 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- ^ a b c Wells, Jeffrey. "Recording of Interview with Alfonso Cuarón" (MP3). Hollywood Elsewhere. 22:55. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ Ross, Bob (5 January 2007). "Hope is as scarce as Children in Dystopian Sci-Fi Thriller". Tampa Tribune.

- ^ a b Rahner, Mark (22 December 2006). "Alfonso Cuarón, director of "Y tu mamá también" searches for hope in "Children of Men"". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ^ Vo, Alex. "Interview with "Children of Men" Director Alfonso Cuarón". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 26 February 2007. Retrieved 23 January 2007.

- ^ Szymanski, Mike (20 December 2006). "Director Alfonso Cuarón and the cast of Children of Men discuss politics, the future and Michael Caine's flatulence". Sci Fi Weekly. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009.

- ^ a b c Alter, Ethan. "Reviews: Children of Men". Film Journal International. Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- ^ Butler, Robert W. (5 January 2007). "Sci-fi movie paints grim future". Kansas City Star.

- ^ von Busack, Richard (10 January 2007). "Making the Future: Richard von Busack talks to Alfonso Cuarón about filming Children of Men". Metroactive. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 23 January 2007.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (7 January 2007). "Beauty and Beasts of England, in a World on Its Last Legs". The New York Times. Awards Season. Retrieved 1 May 2008.

- ^ Anthony Sacramone (8 November 2008). "Children of Men". First Things. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ Simon, Jeff (4 January 2007). "Life Force: Who carries the torch of hope when the world is without children?". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Children of Men". People. Vol. 67, no. 1. 8 January 2007.

- ^ a b Stevens, Dana (21 December 2006). "The Movie of the Millennium". Slate. Retrieved 15 February 2007.

- ^ Richstatter, Katje (March–April 2007). "Two Dystopian Movies...and their Visions of Hope". Tikkun. Vol. 22, no. 2.

- ^ Broxton, Jonathan (17 January 2007). "Children of Men". Movie Music UK. Archived from the original on 28 February 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- ^ Crust, Kevin (17 January 2007). "Unconventional soundscape in Children of Men". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ LaCara, Len (22 April 2007). "Cruelest of months leaves more families grieving". Coshocton Tribune.

- ^ Lowman, Rob (27 March 2007). "Cuaron vs. the world". Los Angeles Daily News.

- ^ Kozma, Andrew; Eldred, Laura (16 January 2007). "Children of Men: Review". RevolutionSF. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ Rowin, Michael Joshua (Spring 2007). "Children of Men". Cineaste. Vol. 32, no. 2. pp. 60–61. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ Bennett, Ray (4 September 2006). "Children of Men". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 20 January 2007. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- ^ a b Dargis, Manohla (25 December 2006). "Apocalypse Now, but in the Wasteland a Child Is Given". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 January 2007.

- ^ Smith, Chris (1 January 2007). "Children of Men a dark film, and one of 2006's best". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved 29 January 2007. [dead link]

- ^ Herrmann, Zachary (14 December 2006). "Championing the Children". The Diamondback. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 4 February 2007.

- ^ Macura-Nnamdi, Ewa (September 2022). "Refugees, Extinction, and the Regulation of Death in Alfonso Cuarón's Children of Men". Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Inquiry. 9 (3): 337–352. doi:10.1017/pli.2022.20. ISSN 2052-2614.

- ^ O'Donnell, Marcus (March 2015). "Children of Men 's Ambient Apocalyptic Visions". The Journal of Religion and Popular Culture. 27 (1): 16–30. doi:10.3138/jrpc.27.1.2439. ISSN 1703-289X. S2CID 152710093.

- ^ Latimer, Heather. "Bio-Reproductive Futurism: Bare Life and the Pregnant Refugee in Alfonso Cuarón's Children of Men". read.dukeupress.edu. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Dalton, Stephen (12 February 2019). "Children of Men: why Alfonso Cuarón's anti-Blade Runner looks more relevant than ever". bfi.org.uk/features. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ "Programme for pass holders and the public" (PDF). Venice International Film Festival. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ Bresnan, Conor (25 September 2006). "Around the World Roundup: "Perfume" Wafts Past "Pirates"". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ Mohr, Ian (4 January 2007). "Men takes a bigger bow". Variety. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ "Children of Men (2006)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

- ^ Children of Men (DVD ed.). Europe and United States. 2007. Archived from the original on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Howell, Peter (29 March 2007). "A stark prophecy". Toronto Star.

- ^ Children of Men (Blu-ray ed.). United States. 26 May 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Children of Men (2006)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ "Children of Men (2006): Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 21 February 2010. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ "Cinemascore". Archived from the original on 20 December 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (4 October 2007). "Baby's day off". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ "Readers' Poll". Film Comment. March–April 2007.

- ^ a b "Metacritic: 2006 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 8 January 2008.

- ^ Geier, Thom; Jensen, Jeff; Jordan, Tina; Lyons, Margaret; Markovitz, Adam; Nashawaty, Chris; Pastorek, Whitney; Rice, Lynette; Rottenberg, Josh; Schwartz, Missy; Slezak, Michael; Snierson, Dan; Stack, Tim; Stroup, Kate; Tucker, Ken; Vary, Adam B.; Vozick-Levinson, Simon; Ward, Kate (12 November 2009). "Ten Best Movies of the Decade!". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 7 December 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ^ Travers, Peter. "Children of Men (2006)". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 25 June 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Film Critics Pick the Best Movies of the Decade". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ Hill, Rob (2010). 501 Must-See Movies (Revised ed.). London: Bounty Books. p. 373. ISBN 9780753719541.

- ^ Barber, Nicholas (15 December 2016). "Why Children of Men has never been as shocking as it is now". BBC. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

Today, it's hard to watch the television news headlines in Children of Men without gasping at their prescience:

- ^ Rodriguez-Cuervo, Ana Yamel (30 November 2015). "Are We Living in the Dawning of Alfonso Cuarón's CHILDREN OF MEN?". TribecaFilm. Retrieved 20 January 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Newton, Mark (22 December 2016). "'Children of Men' 10 Year Anniversary: Why Cuarón's Dystopian Masterpiece Is Even More Relevant Today". Movie Pilot. Archived from the original on 20 January 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ Riesman, Abraham (29 November 2017). "Why 'Children of Men' is the most relevant film of 2017". SBS. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

[...] the 55-year-old director gets a little irritated when I laud the film's imaginative prescience.

- ^ Novak, Matt (9 April 2015). "The Syrian Refugee Crisis Is Our Children of Men Moment". Paleofuture. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ Jacobson, Gavin (22 July 2020). "Why Children of Men haunts the present moment". New Statesman. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ Virtue, Graeme (7 September 2020). "What is the most prescient science fiction film?". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ Russell, Stephen A. (28 May 2019). "Failing fertility and the fight for women's rights in 'Children of Men' and 'The Handmaid's Tale'". SBS. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

Again, hear the harrowing echoes of today's demonisation of the other and the championing of unflinching border security by the likes of Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson...

- ^ Langlo, Karisa (1 January 2023). "The Bizarre Experience of Rewatching 'Children of Men' Today". CNET. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

Children of Men exists strangely in the past, present and future all at once, a relic of the mid-aughts with alarming 2020s prescience and a 2027 setting.

- ^ Perry, Kevin E G (24 December 2021). "Children of Men at 15: 'London in winter is a good place to imagine the end of the world'". The Independent. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

The film has enjoyed a critical resurgence in recent years, at least in part because of how prescient its depiction of an immigration-obsessed, post-apocalyptic Britain now looks.

- ^ Ehrlich, David (16 November 2016). "'Children of Men' Turns 10: Finding Hope in Dystopia for the Age of President Trump". IndieWire. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

[Children of Men] has also proven to be the most prescient...

- ^ "Marc Webb". Sight & Sound Greatest Films Poll. British Film Institute. 2012. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ Sunami, Chris (7 May 2015). "Top 10 Movies: #1 – Children of Men". The Pop Culture Philosopher. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ "The 21st Century's 100 greatest films". BBC. 23 August 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ Weingarten, Christopher R.; Murray, Noel; Schrer, Jenna; Grierson, Tim; Montgomery, James; Fear, David; Marchese, David; Grow, Kory; Tallerico, Brian (22 August 2017). "The Top 40 Sci-Fi Movies of the 21st Century". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ "THE 100 BEST MOVIES OF THE PAST 10 DECADES". Time. 26 July 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ "P.D. James Pleased With Film Version of Children of Men". IWJBlog. 9 January 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- ^ Kit, Boris (13 January 2007). "Scripter goes to Children of Men". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 15 September 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "The 79th Academy Awards (2007) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. AMPAS. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "Film in 2007". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "'Children of Men' tops Cinematographers Guild". Arkansas Times. 19 February 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "Children of Men" cameraman in focus at awards". Reuters. 9 August 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ "Award winners". Australian Cinematographers Society. July 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ "2007 Hugo Awards". TheHugoAwards.org. 9 August 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "'Superman' tops Saturns". Variety. 10 May 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ "Superman Returns Leads the 33rd Annual Saturn Awards with 10 Nominations". Movieweb. 21 February 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ Kit, Boris (13 January 2007). "Scripter goes to Children of Men". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 15 September 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

External links

[edit]- Children of Men at IMDb

- Children of Men at Box Office Mojo

- Children of Men at Metacritic

- Children of Men at Rotten Tomatoes

- 2006 films

- 2000s action drama films

- 2006 action thriller films

- 2006 science fiction action films

- 2000s science fiction adventure films

- 2000s science fiction drama films

- 2000s dystopian films

- American action drama films

- American action thriller films

- American science fiction action films

- American science fiction adventure films

- American science fiction drama films

- American science fiction thriller films

- British action thriller films

- British science fiction action films

- British science fiction adventure films

- British science fiction drama films

- Japanese action drama films

- Japanese action thriller films

- Films about grief

- Japanese science fiction action films

- American dystopian films

- Films about immigration

- Films based on British novels

- Films based on science fiction novels

- Films based on thriller novels

- Films directed by Alfonso Cuarón

- Films produced by Marc Abraham

- Films with screenplays by Alfonso Cuarón

- Films with screenplays by Mark Fergus and Hawk Ostby

- Films set in 2027

- Films set in London

- Films set in Sussex

- Films set in Kent

- Films shot in Buenos Aires

- Films shot in London

- Films shot in Uruguay

- Films shot at Pinewood Studios

- British post-apocalyptic films

- American post-apocalyptic films

- British pregnancy films

- American pregnancy films

- Universal Pictures films

- Beacon Pictures films

- Films about bureaucracy

- BAFTA winners (films)

- 2006 drama films

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s American films

- 2000s British films

- 2000s Japanese films

- English-language Japanese films

- British dystopian films