Coretta Scott King

Coretta Scott King | |

|---|---|

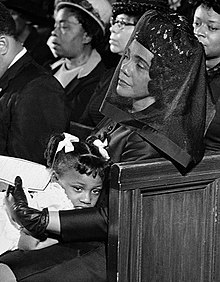

King in 1964 | |

| Born | Coretta Scott April 27, 1927 Heiberger, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | January 30, 2006 (aged 78) Rosarito, Baja California, Mexico |

| Resting place | King Center for Nonviolent Social Change |

| Education | Antioch College (BA) New England Conservatory of Music (BM) |

| Occupations |

|

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Relatives | Edythe Scott Bagley (sister) Alveda King (niece) |

| Awards | Gandhi Peace Prize |

Coretta Scott King (née Scott; April 27, 1927 – January 30, 2006) was an American author, activist, and civil rights leader who was the wife of Martin Luther King Jr. from 1953 until his death. As an advocate for African-American equality, she was a leader for the civil rights movement in the 1960s. King was also a singer who often incorporated music into her civil rights work. King met her husband while attending graduate school in Boston. They both became increasingly active in the American civil rights movement.

King played a prominent role in the years after her husband's assassination in 1968, when she took on the leadership of the struggle for racial equality herself and became active in the Women's Movement. King founded the King Center, and sought to make his birthday a national holiday. She finally succeeded when Ronald Reagan signed legislation which established Martin Luther King, Jr., Day on November 2, 1983. She later broadened her scope to include both advocacy for LGBTQ rights and opposition to apartheid. King became friends with many politicians before and after Martin's death, including John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Robert F. Kennedy. Her telephone conversation with John F. Kennedy during the 1960 presidential election has been credited by historians for mobilizing African-American voters.[1]

In August 2005, King suffered a stroke which paralyzed her right side and left her unable to speak; five months later, she died of respiratory failure due to complications from ovarian cancer. Her funeral was attended by some 10,000 people, including U.S. presidents George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George H. W. Bush and Jimmy Carter. She was temporarily buried on the grounds of the King Center until being interred next to her husband. She was inducted into the Alabama Women's Hall of Fame, the National Women's Hall of Fame, and was the first African American to lie in state at the Georgia State Capitol.[2] King has been referred to as "First Lady of the Civil Rights Movement".[3]

Childhood and education

Coretta Scott was born in Heiberger, Alabama, the third of four children of Obadiah Scott (1899–1998) and Bernice McMurry Scott (1904–1996). She was born in her parents' home, with her paternal great-grandmother Delia Scott, a former slave, presiding as midwife. Coretta's mother became known for her musical talent and singing voice. As a child, Bernice attended the local Crossroads School; her formal education ended with the fourth grade. Bernice's older siblings, however, boarded at the Tuskegee Institute, founded by Booker T. Washington. The senior Mrs. Scott worked as a school bus driver, as a church pianist, and for her husband in his business. She served as Worthy Matron for her Prince Hall Order of the Eastern Starchapter, and was a member of the local Literacy Federated Club.[4][5][6]

Obie, Coretta's father, was one of the first black people in their town to own a vehicle. Before starting his own businesses, he worked as a policeman. Along with his wife, he ran a clothing shop far from their home and later opened a general store. He also owned a lumber mill, which was burned down by white neighbors after Scott refused to sell his mill to a white logger.[7] Her maternal grandparents were Mollie (née Smith; 1868 – d.) and Martin van Buren McMurry (1863–1950) – both were of African-American and Irish descent.[6] Mollie was born a slave to plantation owners Jim Blackburn and Adeline (Blackburn) Smith. Coretta's maternal grandfather, Martin, was born to a slave of Black Native American ancestry, and her white master who never acknowledged Martin as his son. He eventually owned a 280-acre farm. Because of his diverse origins, Martin appeared to be white. However, he displayed contempt for the notion of passing. As a self-taught reader with little formal education, he is noted for having inspired Coretta's passion for education. Coretta's paternal grandparents were Cora (née McLaughlin; 1876 – 1920) and Jefferson F. Scott (1873–1941). Cora died before Coretta's birth. Jeff Scott was a farmer and a prominent figure in the rural black religious community; he was born to former slaves Willis and Delia Scott.[6]

At age 10, Coretta worked to increase the family's income.[8] She had an older sister named Edythe Scott Bagley (1924–2011), an older sister named Eunice who did not survive childhood, and a younger brother named Obadiah Leonard (1930–2012).[9] The Scott family had owned a farm since the American Civil War, but were not particularly wealthy.[10] During the Great Depression the Scott children picked cotton to help earn money[9] and shared a bedroom with their parents.[11]

Coretta described herself as a tomboy during her childhood, primarily because she could climb trees and recalled wrestling boys. She also mentioned having been stronger than a male cousin and threatening before accidentally cutting that same cousin with an axe. His mother threatened her, and along with the words of her siblings, stirred her to becoming more ladylike once she got older. She saw irony in the fact that despite these early physical activities, she still was involved in nonviolent movements.[12] Her brother Obadiah thought she always "tried to excel in everything she did."[13] Her sister Edythe believed her personality was like that of their grandmother Cora McLaughlin Scott, after whom she was named.[14] Though lacking formal education themselves, Coretta Scott's parents intended for all of their children to be educated. Coretta quoted her mother as having said, "My children are going to college, even if it means I only have but one dress to put on."[15]

The Scott children attended a one-room elementary school 5 miles (8 km) from their home and were later bused to Lincoln Normal School, which despite being 9 mi (14 km) from their home, was the closest black high school in Marion, Alabama, due to racial segregation in schools. The bus was driven by Coretta's mother Bernice, who bused all the local black teenagers.[9] By the time Scott had entered the school, Lincoln had suspended tuition and charged only four dollars and fifty cents per year.[16] In her last two years there, Scott became the leading soprano for the school's senior chorus. Scott directed a choir at her home church in North Perry Country.[17] Coretta Scott graduated valedictorian from Lincoln Normal School in 1945, where she played trumpet and piano, sang in the chorus, and participated in school musicals and enrolled at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio during her senior year at Lincoln. After being accepted to Antioch, she applied for the Interracial Scholarship Fund for financial aid.[18] During her last two years in high school, Coretta lived with her parents.[19] Her older sister Edythe already attended Antioch as part of the Antioch Program for Interracial Education, which recruited non-white students and gave them full scholarships in an attempt to diversify the historically white campus. Coretta said of her first college:

Antioch had envisioned itself as a laboratory in democracy but had no black students. (Edythe) became the first African American to attend Antioch on a completely integrated basis, and was joined by two other black female students in the fall of 1943. Pioneering is never easy, and all of us who followed my sister at Antioch owe her a great debt of gratitude.[15]

Coretta studied music with Walter Anderson, the first non-white chair of an academic department in a historically white college. She also became politically active, due largely to her experience of racial discrimination by the local school board. She became active in the nascent civil rights movement; she joined the Antioch chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the college's Race Relations and Civil Liberties Committees. The board denied her request to perform her second year of required practice teaching at Yellow Springs public schools, for her teaching certificate Coretta Scott appealed to the Antioch College administration, which was unwilling or unable to change the situation in the local school system and instead employed her at the college's associated laboratory school for a second year. Additionally, around this time, Coretta worked as a babysitter for the Lithgow family, babysitting the later prominent actor John Lithgow.[20]

New England Conservatory of Music and Martin Luther King Jr.

Coretta transferred out of Antioch when she won a scholarship to the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. It was while studying singing at that school with Marie Sundelius that she met Martin Luther King Jr.[21] after mutual friend Mary Powell gave King her phone number after he asked about girls on the campus. Coretta was the only one remaining after Powell named two girls and King proved to not be impressed with the other. Scott initially showed little interest in meeting him, even after Powell told her that he had a promising future, but eventually relented and agreed to the meeting. King called her on the telephone and when the two met in person, Scott was surprised by how short he was. King would tell her that she had all the qualities that he was looking for in a wife, which Scott dismissed since the two had only just met.[22] She told him "I don't see how you can say that. You don't even know me." But King was assured and asked to see her again. She readily accepted his invitation to a weekend party.[23]

She continued to see him regularly in the early months of 1952. Two weeks after meeting Scott, King wrote to his mother that he had met his wife.[24] Their dates usually consisted of political and racial discussions, and in August of that year Coretta met King's parents Martin Luther King Sr. and Alberta Williams King.[25] Before meeting Martin, Coretta had been in relationships her entire time in school but never had any she cared to develop.[26] Once meeting with her sister Edythe face-to-face, Coretta detailed her feelings for the young aspiring minister and discussed the relationship as well. Edythe was able to tell her sister had legitimate feelings for him, and she also became impressed with his overall demeanor.[27]

Despite envisioning a career for herself in the music industry, Coretta knew that it would not be possible if she were to marry King. However, since King possessed many of the qualities she liked in a man, she found herself "becoming more involved with every passing moment." When asked by her sister what made King so "appealing" to her she responded, "I suppose it's because Martin reminds me so much of our father." At that moment, Scott's sister knew King was "the one".[27]

King's parents visited him in the fall and had suspicions about Coretta Scott after seeing how clean his apartment was. While the Kings had tea and meals with their son and Scott, Martin Sr. turned his attention to her and insinuated that her plans of a career in music were not fitting for a Baptist minister's wife. After Coretta did not respond to his questioning of their romance being serious, Martin Sr. asked if she took his son "seriously".[28] King's father also told her that there were many other women his son was interested in and had "a lot to offer". After telling him that she had "a lot to offer" as well, Martin Luther King Sr. and his wife went on to try and meet with members of Coretta's family. Once the two obtained Edythe's number from Coretta, they sat down with her and had lunch with her. During their time together, Martin Luther King Sr. tried to ask Edythe about the relationship between her sister and his son. Edythe insisted that her sister was an excellent choice for Martin Luther King Jr., but also felt that Coretta did not need to bargain for a husband.[29]

On Valentine's Day 1953, the couple announced their plans to marry in the Atlanta Daily World. With a wedding set in June, only four months away at that time, Coretta still did not have a commitment to marrying King and consulted with her sister in a letter sent just before Easter Vacation.[29] King's father had expressed resentment in his choice of Coretta over someone from Alabama and accused his son of spending too much time with her and neglecting his studies.[30] Martin took his mother into another room and told her of his plans to marry Coretta and told her the same thing when he drove her home later while also berating her for not having made a good impression on his father.[28] When Martin declared his intentions to get a doctorate and marry Coretta after, Martin Sr. finally gave his blessing.[30] In 1964, the Time profile of Martin, when he was chosen as Time's "Man of the Year", referred to her as "a talented young soprano".[31] She was a member of Alpha Kappa Alpha.[32]

Coretta Scott and Martin Luther King Jr. were married on June 18, 1953, on the lawn of her mother's house; the ceremony was performed by Martin Sr. Coretta had the vow to obey her husband removed from the ceremony, which was unusual for the time. After completing her degree in voice and piano at the New England Conservatory, she moved with her husband to Montgomery, Alabama, in September 1954. Mrs. King recalled: "After we married, we moved to Montgomery, Alabama, where my husband had accepted an invitation to be the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. Before long, we found ourselves in the middle of the Montgomery bus boycott, and Martin was elected leader of the protest movement. As the boycott continued, I had a growing sense that I was involved in something so much greater than myself, something of profound historic importance. I came to the realization that we had been thrust into the forefront of a movement to liberate oppressed people, not only in Montgomery but also throughout our country, and this movement had worldwide implications. I felt blessed to have been called to be a part of such a noble and historic cause."[33]

Civil Rights Movement

On September 1, 1954, Martin became the full-time pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. King's devotion to the cause while giving up on her own musical ambitions would become symbolic of the actions of African-American women during the movement.[34] The couple moved into the church's parsonage on South Jackson Street shortly after this. Coretta became a member of the choir and taught Sunday school, as well as participating in the Baptist Training Union and Missionary Society. She made her first appearance at the First Baptist Church on March 6, 1955, where according to E. P. Wallace, she "captivated her concert audience".[35]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The Kings' first child was born on November 17, 1955, and was named Yolanda at Coretta's insistence.[36] After Martin Luther King became involved in the Montgomery bus boycott, Mrs. King often received threats directed towards him. In January 1956, she answered numerous phone calls threatening her husband's life, as rumors intended to make African Americans dissatisfied with Martin Luther King spread that he had purchased a Buick station wagon for her.[37] Martin would give her[who?] the nickname "Yoki", and thereby, allow himself to refer to her out of her name. By the end of the boycott, the Kings had come to believe in nonviolent protests as a way of expression consistent with biblical teachings.[38] Two days after the integration of Montgomery's bus service, on December 23, a gunshot rang through the front door of the King home while the King family were asleep. The three were not harmed.[39] On Christmas Eve of 1955, King took her daughter to her parents' house and met with her siblings as well. Yolanda was their first grandchild. Martin joined them the next day, at dinner time.[40]

On February 21, 1956, Martin Luther King said he would return to Montgomery after picking up Coretta and their daughter from Atlanta, who were staying with his parents. During Martin Sr.'s opposition to his son's choice to return to Montgomery, Mrs. King picked up her daughter and went upstairs, which he would express dismay in later and tell her that she "had run out on him". Two days later, Coretta and Martin Luther King drove back to Montgomery.[41] Coretta took an active role in advocating for civil rights legislation. On April 25, 1958, King made her first appearance at a concert that year at Peter High School Auditorium in Birmingham, Alabama. With a performance sponsored by the Omicron Lambda chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, King changed a few songs in the first part of the show but still continued with the basic format used two years earlier at the New York gala as she told the story of the Montgomery bus boycott. The concert was important for Coretta as a way to continue her professional career and participate in the movement. The concert gave the audience "an emotional connection to the messages of social, economic, and spiritual transformation."[42]

On September 3, 1958, King accompanied her husband and Ralph Abernathy to a courtroom. Martin was arrested outside the courtroom for "loitering" and "failing to obey an officer".[43] A few weeks later, King visited Martin's parents in Atlanta. At that time, she learned that he had been stabbed while signing copies of his book Stride Toward Freedom on September 20, 1958. King rushed to see her husband, and stayed with him for the remainder of his time in the hospital recovering.[44] On February 3, 1959, Mr. and Mrs. King and Lawrence D. Reddick started a five-week tour of India. The three were invited to hundreds of engagements.[45] During their trip, Coretta used her singing ability to enthuse crowds during their month-long stay. The two returned to the United States on March 10, 1959.[46]

House bombing

On January 30, 1956, Coretta and Dexter congregation member Roscoe Williams' wife Mary Lucy heard the "sound of a brick striking the concrete floor of the front porch." Coretta suggested that the two women get out of the front room and went into the guest room, as the house was disturbed by an explosion which caused the house to rock and fill the front room with smoke and shattered glass. The two went to the rear of the home, where Yolanda was sleeping and Coretta called the First Baptist Church and reported the bombing to the woman who answered the phone.[47] Martin returned to their home, and upon finding Coretta and his daughter unharmed, went outside. He was confronted by an angry crowd of his supporters, who had brought guns. He was able to turn them away with an impromptu speech.[48]

A white man was reported by a lone witness to have walked halfway up to King's door and thrown something against the door before running back to his car and speeding off. Ernest Walters, the lone witness, did not manage to get the license plate number because of how quickly the events transpired.[49] Both of the couple's fathers contacted them over the bombing. The two arrived nearly at the same time, along with her Martin Luther King's mother and brother. Coretta's father Obie said he would take her and her daughter back to Marion if his son-in-law did not take them to Atlanta. Coretta refused the proclamation and insisted on staying with her husband.[50] Despite Martin Sr. also advocating that she leave with her father, King persisted in leaving with him. Author Octavia B. Vivian wrote "That night Coretta lost her fear of dying. She committed herself more deeply to the freedom struggle, as Martin had done four days previously when jailed for the first time in his life." Coretta would later call it the first time she realized "how much I meant to Martin in terms of supporting him in what he was doing".[51]

John F. Kennedy phone call

Martin Luther King Jr. was jailed on October 19, 1960, in a department store. After being released three days later, he was sent back to jail on October 22 for driving with an Alabama license while being a resident of Georgia and was sent to jail for four months of hard labor. After his arrest, Mrs. King believed he would not make it out alive and telephoned her friend Harris Wofford and cried while saying "They're going to kill him. I know they are going to kill him." Directly after speaking with her, Wofford contacted Sargent Shriver in Chicago, where presidential candidate John F. Kennedy, was campaigning at the time and told Shriver of King's fears for her husband. After Shriver waited to be with Kennedy alone, he suggested that he telephone King and express sympathy.[52] Kennedy called King, after agreeing to the proposal.[1]

Sometime afterward, Robert F. Kennedy obtained King's release from prison. Martin Sr. was so grateful for the release that he voted for Kennedy and said: "I'll take a Catholic or the devil himself if he'll wipe the tears from my daughter-in-law's eyes."[53] According to Coretta, Kennedy said "I want to express my concern about your husband. I know this must be very hard on you. I understand you are expecting a baby, and I just want you to know that I was thinking about you and Dr. King. If there is anything I can do to help, please feel free to call on me." Kennedy's contact with King was learned about quickly by reporters, with Coretta admitting that it "made me feel good that he called me personally and let me know how he felt."[54]

Kennedy presidency

Mr. and Mrs. King had come to respect President Kennedy and understood his reluctance at times to get involved openly with civil rights.[55] In April 1962, Coretta served as a delegate for the Women Strike for Peace Conference in Geneva, Switzerland.[56] Martin drove her to the hospital on March 28, 1963, where King gave birth to their fourth child Bernice. After King and her daughter were due to come home, Martin rushed back to drive them himself.[57] After Martin Luther King's arrest on April 12, 1963, King tried to make direct contact with President Kennedy at the advisement of Wyatt Tee Walker and succeeded in speaking with Robert F. Kennedy. President Kennedy was with his father Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr, who was not feeling well.[58] In what has been noted as making Kennedy seem less sympathetic towards the Kings, the president redirected Mrs. King's call to the White House switchboard.[59]

The next day, President Kennedy reported to King that the FBI had been sent into Birmingham the previous night and confirmed that her husband was fine. He was allowed to speak with her on the phone and told her to inform Walker of Kennedy's involvement.[60] She told her husband of her assistance from the Kennedys, which her husband took as the reason "why everybody is suddenly being so polite."[61] Regarding the March on Washington, Coretta said, "It was as though heaven had come down."[62] Coretta had been home all day with their children, since the birth of their daughter Bernice had not allowed her to attend Easter Sunday church services.[63] Since Mrs. King had issued her own statement regarding the aid of the president instead of doing as her husband had told her and report to Wyatt Walker, this according to author Taylor Branch, made her portrayed by reports as "an anxious new mother who may have confused her White House fantasies with reality."[59]

Coretta went to a Women Strike for Peace rally in New York, in the early days of November 1963. After speaking at the meeting held in the National Baptist Church, King joined the march from Central Park to the United Nations Headquarters. The march was timed to celebrate the group's second anniversary and celebrated the successful completion of the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. Coretta and Martin learned of John F. Kennedy's assassination when reports initially indicated he had only been seriously wounded. Coretta joined her husband upstairs and watched Walter Cronkite announce the president's death. King sat with her visibly shaken husband following the confirmation.[64]

FBI tapes

The FBI planned to mail tapes of her husband's alleged affairs to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference office since surveillance revealed that Coretta opened her husband's mail when he was traveling. The FBI learned that Martin Luther King would be out of office by the time the tapes were mailed and that his wife would be the one to open it.[65] J. Edgar Hoover even advised to mail "it from a southern state."[66] Coretta sorted the tapes with the rest of the mail, listened to them, and immediately called her husband, "giving the Bureau a great deal of pleasure with the tone and tenor of her reactions."[67] Martin Luther King played the tape in her presence, along with Andrew Young, Ralph Abernathy and Joseph Lowery. Publicly, Mrs. King would say "I couldn't make much out of it, it was just a lot of mumbo-jumbo."[68] The tapes were part of a larger attempt by J. Edgar Hoover to denounce King by revelations about his personal life.[69]

Johnson presidency

Most prominently, perhaps, she worked hard to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964. King spoke with Malcolm X days before his assassination. Malcolm told her that he was not in Alabama to make trouble for her husband, but instead to make white people have more appreciation for King's protests, seeing his alternative.[70] On March 26, 1965, King's father joined her and her husband for a march that would later end in Montgomery. Her father "caught a glimpse of America's true potential" and for the called it "the greatest day in the whole history of America" after seeing chanting for his daughter's husband by both Caucasians and African Americans.[71]

Coretta Scott King criticized the sexism of the Civil Rights Movement in January 1966 in New Lady magazine, saying in part, "Not enough attention has been focused on the roles played by women in the struggle. By and large, men have formed the leadership in the civil rights struggle but ... women have been the backbone of the whole civil rights movement."[72] Martin Luther King Jr. himself limited Coretta's role in the movement, and expected her to be a housewife.[72] King participated in a Women Strike for Peace protest in January 1968, at the capital of Washington, D.C., with over five thousand women. In honor of the first woman elected to the House of Representatives, the group was called the Jeannette Rankin Brigade. Coretta co-chaired the Congress of Women conference with Pearl Willen and Mary Clarke.[73] At some point in his activities, Martin suggested that the people working with him should organize a "sex party".[74]

Assassination of her husband

Martin Luther King Jr. was shot and killed in Memphis, Tennessee on April 4, 1968. She learned of the shooting after being called by Jesse Jackson when she returned from shopping with her eldest child Yolanda.[75] King had difficulty settling her children with the news that their father was deceased. She received a large number of telegrams, including one from Lee Harvey Oswald's mother, which she regarded as the one that touched her the most.[76][citation needed]

In an effort to prepare her daughter Bernice, then only five years old, for the funeral, she tried to explain to her that the next time she saw her father he would be in a casket and would not be speaking.[77] When asked by her son Dexter when his father would return, King lied and told him that his father had only been badly hurt. Senator Robert F. Kennedy ordered three more telephones to be installed in the King residence for King and her family to be able to answer the flood of calls they received and offered a plane to transport her to Memphis.[78] Coretta spoke to Kennedy the day after the assassination and asked if he could persuade Jacqueline Kennedy to attend her husband's funeral with him.[79]

Robert F. Kennedy promised her that he would help "any way" he could. King was told to not go ahead and agree to Kennedy's offer by Southern Christian Leadership Conference members, who told her about his presidential ambitions. She ignored the warnings and went along with his request.[80] On April 5, 1968, King arrived in Memphis to retrieve her husband's body and decided that the casket should be kept open during the funeral with the hope that her children would realize upon seeing his body that he would not be coming home.[78] King called photographer Bob Fitch and asked for documentation to be done, having known him for years.[81] On April 7, 1968, former Vice President Richard Nixon visited King and recalled his first meeting with her husband in 1955. Nixon also went to Martin Luther King, Jr.'s funeral on April 9, 1968, but did not walk in the procession. Nixon believed participating in the procession would be "grandstanding".[82]

On April 8, 1968, King and her children headed a march with sanitation workers that her husband had planned to carry out before his death. After the marchers reached the staging area at the Civic Center Plaza in front of Memphis City Hall, onlookers proceeded to take pictures of King and her children but stopped when she addressed everyone at a microphone. She said that despite the Martin Luther King Jr. being away from his children at times, "his children knew that Daddy loved them, and the time that he spent with them was well spent."[83] Prior to Martin's funeral, Jacqueline Kennedy met with her. The two spent five minutes together and despite the short visit, Coretta called it comforting. King's parents arrived from Alabama.[84] Robert and Ethel Kennedy came, the latter being embraced by King.[85] King and her sister-in-law Christine King Farris tried to prepare the children for seeing Martin's body.[86] With the end of the funeral service, King led her children and mourners in a march from the church to Morehouse College, her late husband's alma mater.[87]

Early widowhood

Two days after her husband's death, King spoke at Ebenezer Baptist Church and made her first statement on his views since he had died. She said her husband told their children, "If a man had nothing that was worth dying for, then he was not fit to live." She brought up his ideals and the fact that he may be dead, but concluded that "his spirit will never die."[88] Not very long after the assassination, Coretta took his place at a peace rally in New York City. Using notes he had written before his death, King constructed her own speech.[89] Coretta approached the African-American entertainer and activist Josephine Baker to take her husband's place in the Civil Rights Movement. Baker declined after thinking it over, stating that her twelve adopted children (known as the "rainbow tribe") were "too young to lose their mother".[90]

Coretta Scott King eventually broadened her focus to include women's rights, LGBT rights, economic issues, world peace, and various other causes. As early as December 1968, she called for women to "unite and form a solid block of women power to fight the three great evils of racism, poverty and war", during a Solidarity Day speech.[91] On April 27, 1968, King spoke at an anti-war demonstration in Central Park in place of her husband. King made it clear that there was no reason "why a nation as rich as ours should be blighted by poverty, disease, and illiteracy."[92] King used notes taken from her husband's pockets upon his death, which included the "Ten Commandments on Vietnam".[93] On June 5, 1968, Bobby Kennedy was shot after winning the California primary for the Democratic nomination for President of the United States. After he died the following day, Ethel Kennedy, who King had spoken to with her husband only two months earlier, was widowed. King flew to Los Angeles to comfort Ethel over Bobby's death.[94] On June 8, 1968, while King was attending the late senator's funeral, the Justice Department made the announcement of James Earl Ray's arrest.[95]

Not long after this, the King household was visited by Mike Wallace, who wanted to visit her and the rest of her family and see how they were faring that coming Christmas. She introduced her family to Wallace and also expressed her belief that there would not be another Martin Luther King Jr. because he comes around "once in a century" or "maybe once in a thousand years". She furthered that she believed her children needed her more than ever and that there was hope for redemption in her husband's death.[96] In January 1969, King and Bernita Bennette left for a trip to India. Before arriving in the country, the two stopped in Verona, Italy and King was awarded the Universal Love Award. King became the first non-Italian to receive the award. King traveled to London with her sister, sister-in-law, Bernita and several others to preach at St. Paul's Cathedral. Before, no woman had ever delivered a sermon at a regularly appointed service in the cathedral.[97]

As a leader of the movement, King founded the King Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta. She served as the center's president and CEO from its inception until she passed the reins of leadership to son Dexter Scott King. Removing herself from leadership, allowed her to focus on writing, public speaking and spend time with her parents.[98]

She published her memoirs, My Life with Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1969. President Richard Nixon was advised against visiting her on the first anniversary of his death since it would "outrage" many people.[99] On October 15, 1969, King was the lead speaker at the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam demonstration in Washington D.C., where she led a crowd down Pennsylvania Avenue past the White Past bearing candles and at a subsequent speech she denounced the war in Vietnam.[100]

Coretta Scott King was also under surveillance by the Federal Bureau of Investigation from 1968 until 1972. Her husband's activities had been monitored during his lifetime. Documents obtained by a Houston, Texas television station show that the FBI worried that Coretta Scott King would "tie the anti-Vietnam movement to the civil rights movement."[101] The FBI studied her memoir and concluded that her "selfless, magnanimous, decorous attitude is belied by ... [her] actual shrewd, calculating, businesslike activities."[102] A spokesman for the King family said that they were aware of the surveillance, but had not realized how extensive it was.

Later life

Every year after the assassination of her husband in 1968, Coretta attended a commemorative service at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta to mark his birthday on January 15. She fought for years to make it a national holiday. In 1972, she said that there should be at least one national holiday a year in tribute to an African-American man, "and, at this point, Martin is the best candidate we have."[103] Murray M. Silver, an Atlanta attorney, made the appeal at the services on January 14, 1979. Coretta Scott King later confirmed that it was the "best, most productive appeal ever". Coretta Scott King was finally successful in this campaign in 1986, when Martin Luther King Jr. Day was made a federal holiday.

After the death of J. Edgar Hoover, King made no attempt to hide her bitterness towards him for his work against her husband in a long statement.[104] Coretta Scott King attended the state funeral of Lyndon B. Johnson in 1973, as a very close friend of the former president. On July 25, 1978, King held a press conference in defense of then-Ambassador Andrew Young and his controversial statement on political prisoners in American jails.[105] On September 19, 1979, King visited the Lyndon B. Johnson ranch to meet with Lady Bird Johnson.[106] In 1979 and 1980 Dr. Noel Erskine and King co-taught a class on "The Theology of Martin Luther King, Jr." at the Candler School of Theology (Emory University). On September 29, 1980, King's signing as a commentator for CNN was announced by Ted Turner.[107]

On August 26, 1983, King resented endorsing Jesse Jackson for president, since she wanted to back up someone she believed could beat Ronald Reagan, and dismissed her husband becoming a presidential candidate had he lived.[108] On June 26, 1985, King was arrested with her daughter Bernice and son Martin Luther King III while taking part in an anti-apartheid protest at the Embassy of South Africa in Washington, D.C.[109]

When President Ronald Reagan signed legislation establishing the Martin Luther King Jr. Day, she was at the event. Reagan called her to personally apologize for a remark he made during a nationally televised conference, where he said we would know in "35 years" whether or not King was a communist sympathizer. Reagan clarified his remarks came from the fact that the papers had been sealed off until the year 2027.[110] King accepted the apology and pointed out the Senate Select Committee on Assassinations had not found any basis to suggest her husband had communist ties.[111] On February 9, 1987, eight civil rights activists were jailed for protesting the exclusion of African Americans during the filming of The Oprah Winfrey Show in Cumming, Georgia. Oprah Winfrey tried to find out why the "community has not allowed black people to live there since 1912." King was outraged over the arrests, and wanted members of the group, "Coalition to End Fear and Intimidation in Forsyth County", to meet with Georgia Governor Joe Frank Harris to "seek a just resolution of the situation."[112] On March 8, 1989, King lectured hundreds of students about the civil rights movement at the University of San Diego. King tried to not get involved in the controversy around the naming of the San Diego Convention Center after her husband. She maintained it was up to the "people within the community" and that people had tried to get her involved in with "those kind of local situations."[113]

On January 17, 1993, King showed disdain for the U.S. missile attack on Iraq. In retaliation, she suggested peace protests.[114] On February 16, 1993, King went to the FBI Headquarters and gave an approving address on Director William S. Sessions for having the FBI "turn its back on the abuses of the Hoover era."[115] King commended Sessions for his "leadership in bringing women and minorities into the FBI and for being a true friend of civil rights." King admitted that she would not have accepted the arrangement had it not been for Sessions, the then-current director.[116] On January 17, 1994, the day marking the 65th birthday of her husband, King said: "No injustice, no matter how great, can excuse even a single act of violence against another human being."[117] In January 1995, Qubilah Shabazz was indicted on charges of using telephones and crossing state lines in a plot to kill Louis Farrakhan. King defended her, saying at Riverside Church in Harlem that federal prosecutors targeted her to tarnish her father Malcolm X's legacy.[118] During the fall of 1995, King chaired an attempt to register one million African American female voters for the presidential election next year with fellow widows Betty Shabazz and Myrlie Evers and was saluted by her daughter Yolanda in a Washington hotel ballroom.[119] On October 12, 1995, King spoke about the O. J. Simpson murder case, which she negated having a long-term effect on relations between races when speaking to an audience at Soka University in Aliso Viejo, California.[120] On January 24, 1996, King delivered a 40-minute speech at the Loyola University's Lake Shore campus in Rogers Park. She called for everyone to "pick up the torch of freedom and lead America towards another great revolution."[121] On June 1, 1997, Betty Shabazz suffered extensive and life-threatening burns after her grandson Malcolm Shabazz started a fire in their home. In response to the hospitalization of her longtime friend, King donated $5,000 to a rehabilitation fund for her.[122] Shabazz died on June 23, 1997, three weeks after being burned.

During the 1990s, King was subject to multiple break-ins and encountered Lyndon Fitzgerald Pace, a man who admitted killing women in the area. He broke into the house in the middle of the night and found her while she was sitting in her bed. After nearly eight years of staying in the home following the encounter, King moved to a condominium unit which had also been the home, albeit part-time, for singers Elton John and Janet Jackson.[123] Her new home was a gift from Oprah Winfrey.[124][125] In 1999, the King family finally succeeded in getting a jury verdict saying her husband was the victim of a murder conspiracy after suing Loyd Jowers, who claimed six years prior to having paid someone other than James Earl Ray to kill her husband.[126] On April 4, 2000, King visited her husband's grave with her sons, daughter Bernice and sister-in-law. Regarding plans to construct a monument for her husband in Washington, D.C., King said it would "complete a group of memorials in the nation's capital honoring democracy's greatest leaders, including Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and now Martin Luther King, Jr."[127] The National Park Service wanted to commemorate Martin Luther King's dream, but they did not want any discussion of his opposition to the war in Vietnam or to his struggle to end poverty in America. Coretta Scott King fought to ensure that her husband's legacy was not distorted and the history told at his monument in Washington D.C., was true to the Civil Rights Movement.[128] She became vegan in the last 10 years of her life.[129][130]

Opposition to apartheid

During the 1980s, Coretta Scott King reaffirmed her long-standing opposition to apartheid, participating in a series of sit-in protests in Washington, D.C., that prompted nationwide demonstrations against South African racial policies.

King had a 10-day trip to South Africa in September 1986.[131] On September 9, 1986, she cancelled meeting President P. W. Botha and Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi.[132] The next day, she met with Allan Boesak. The UDF leadership, Boesak and Winnie Mandela had threatened to avoid a meeting King if she met with Botha and Buthelezi.[133] She also met with Winnie Mandela that day, and called it "one of the greatest and most meaningful moments of my life." Nelson Mandela was still being imprisoned in Pollsmoor Prison after being transferred from Robben Island in 1982. Prior to leaving the United States for the meeting, King drew comparisons between the civil rights movement and Mandela's case.[134] Upon her return to the United States, she urged Reagan to approve economic sanctions against South Africa.

Peacemaking

Coretta Scott King was a long-time advocate for world peace. Author Michael Eric Dyson has called her "an earlier and more devoted pacifist than her husband."[135] Although King would object to the term "pacifism", she was an advocate of non-violent direct action to achieve social change. In 1957, King was one of the founders of The Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (now called Peace Action),[136] and she spoke in San Francisco while her husband spoke in New York at the major anti-Vietnam war march on April 15, 1967, organized by the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam.

King was vocal in her opposition to capital punishment and the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[137]

LGBT equality

In August 1983, in Washington, D. C., she urged amendment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to include gays and lesbians as a protected class.[138]

In response to the Supreme Court's 1986 decision in Bowers v. Hardwick that there was no constitutional right to engage in consensual sodomy, King's long-time friend, Winston Johnson of Atlanta, came out to her and was instrumental in arranging King as the featured speaker at the September 27, 1986, New York Gala of the Human Rights Campaign Fund. As reported in the New York Native, King stated that she was there to express her solidarity with the gay and lesbian movement. She applauded gays as having "always been a part of the civil rights movement".[139]

On April 1, 1998, at the Palmer House Hilton in Chicago, King called on the civil rights community to join in the struggle against homophobia and anti-gay bias. "Homophobia is like racism and anti-Semitism and other forms of bigotry in that it seeks to dehumanize a large group of people, to deny their humanity, their dignity and personhood", she stated.[140] "This sets the stage for further repression and violence that spread all too easily to victimize the next minority group."

On March 31, 1998, at the 25th anniversary luncheon for the Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, King said: "I still hear people say that I should not be talking about the rights of lesbian and gay people, and I should stick to the issue of racial justice. ... But I hasten to remind them that Martin Luther King, Jr., said, 'Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.' ... I appeal to everyone who believes in Martin Luther King, Jr.'s, dream to make room at the table of brotherhood and sisterhood for lesbian and gay people."[141][142][143] On November 9, 2000, she repeated similar remarks at the opening plenary session of the 13th annual Creating Change Conference, organized by the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.[144][145][146][147]

In 2003, she invited the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force to take part in observances of the 40th anniversary of the March on Washington and Martin Luther King's I Have a Dream speech. It was the first time that an LGBT rights group had been invited to a major event of the African-American community.[148]

Her funeral was conducted by Bishop Eddie Long, which has been criticized by then-NAACP chairman Julian Bond who refused to attend it, stating that he "just couldn't imagine that she'd want to be in that church with a minister who was a raving homophobe".[149]

The King Center

Established in 1968 by Coretta Scott King, The King Center is the official memorial dedicated to the advancement of the legacy and ideas of Martin Luther King Jr., leader of a nonviolent movement for justice, equality, and peace. Two days after her husband's funeral, King began planning $15 million for funding the memorial.[150] She handed the reins as CEO and president of the King Center down to her son, Dexter Scott King.[151] The Kings initially had difficulty gathering the papers since they were in different locations, including colleges he attended and archives. King had a group of supporters begin gathering her husband's papers in 1967, the year before his death.[152] After raising funds from a private sector and the government, she financed the building of the complex in 1981.[153]

In 1984, she came under criticism by Hosea Williams, one of her husband's earliest followers, for having used the King Center to promote "authentic material" on her husband's dreams and ideals, and disqualified the merchandise as an attempt to exploit her husband. She sanctioned the kit, which contained a wall poster, five photographs of King and his family, a cassette of the I Have a Dream speech, a booklet of tips on how to celebrate Martin Luther King Jr. Day and five postcards with quotations from King himself. She believed it to be the authentic way to celebrate the holiday honoring her husband, and denied Hosea's claims.[154]

King sued her husband's alma mater of Boston University over who would keep over 83,000 documents in December 1987 and said the documents belonged with the King archives. However, her husband was held to his word by the university; he had stated after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 that his papers would be kept at the college. Coretta's lawyers argued that the statement was not binding and mentioned that King had not left a will at the time of his death.[155] King testified that President of Boston University John R. Silber in a 1985 meeting demanded that she send the university all of her husband's documents instead of the other way around.[156] King released the statement, "Dr. King wanted the south to be the repository of the bulk of his papers. Now that the King Center library and archives are complete and have one of the finest civil-rights collections in all the world, it is time for the papers to be returned home."[157]

On January 17, 1992, President George H. W. Bush laid a wreath at the tomb of her husband and met with and was greeted by King at the center. King praised Bush's support for the holiday, and joined hands with him at the end of a ceremony and sang "We Shall Overcome".[158] On May 6, 1993, a court rejected her claims to the papers after finding that a July 16, 1964 letter from Martin Luther King to the institute had constituted a binding charitable pledge to the university and outright stating that Martin Luther King retained ownership of his papers until giving them to the university as gifts or his death. King, however, said her husband had changed his mind about allowing Boston University to keep the papers.[159] After her son Dexter took over as the president of the King Center for the second time in 1994, King was given more time to write, address issues and spend time with her parents.[160]

Coretta Scott King Center for Cultural and Intellectual Freedom

In 2005, King gifted the use of her name to her alma mater, Antioch College in Yellow Springs, to create the Coretta Scott King Center as an experiential learning resource to address issues of race, class, gender, diversity, and social justice for the campus and the surrounding community. The center opened in 2007 on the Antioch College campus.

The center lists its mission as "The Coretta Scott King Center facilitates learning, dialogue, and action to advance social justice", and its vision as "To transform lives, the nation and the world by cultivating change agents, collaborating with communities, and fostering networks to advance human rights and social justice."[161]

Illness and death

By the end of her 77th year, Coretta began experiencing health problems. Her husband's former secretary, Dora McDonald, assisted her part-time in this period.[162] Hospitalized in April 2005, a month after speaking in Selma at the 40th anniversary of the Selma Voting Rights Movement, she was diagnosed with a heart condition and was discharged on her 78th and final birthday. Later, she suffered several small strokes. On August 16, 2005, she was hospitalized after suffering a stroke and a mild heart attack. Initially, she was unable to speak or move her right side. King's daughter Bernice reported that she had been able to move her leg on Sunday, August 21[163] while her other daughter and oldest child Yolanda asserted that the family expected her to fully recover.[164] She was released from Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta on September 22, 2005, after regaining some of her speech and continued physiotherapy at home. Due to continuing health problems, King canceled a number of speaking and traveling engagements throughout the remainder of 2005. On January 14, 2006, Coretta made her last public appearance in Atlanta at a dinner honoring her husband's memory. On January 26, 2006, King checked into a rehabilitation center in Rosarito Beach, Mexico under a different name. Doctors did not learn her real identity until her medical records arrived the next day, and did not begin treatment due to her condition.[165]

Coretta Scott King died on the late evening of January 30, 2006,[166] at the rehabilitation center in Rosarito Beach, Mexico, in the Oasis Hospital where she was undergoing holistic therapy for her stroke and advanced-stage ovarian cancer. The main cause of her death is believed to be respiratory failure due to complications from ovarian cancer.[166] The clinic at which she died was called the Hospital Santa Mónica, but was licensed as Clínica Santo Tomás. After reports indicated that it was not legally licensed to "perform surgery, take X-rays, perform laboratory work or run an internal pharmacy, all of which it was doing", as well as reports of it being operated by highly controversial medical figure Kurt Donsbach, it was shut down by medical commissioner Dr. Francisco Versa.[167][168] King's body was flown from Mexico to Atlanta on February 1, 2006.[169]

King's eight-hour funeral at the New Birth Missionary Baptist Church in Lithonia, Georgia was held on February 7, 2006. Bernice King delivered her eulogy. U.S. Presidents George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George H. W. Bush and Jimmy Carter attended, as did their wives, with the exception of former First Lady Barbara Bush who had a previous engagement. The Ford family was absent due to the illness of President Ford (who himself died later that year). Senator and future President Barack Obama, among other elected officials,[170] attended the televised service.

President Jimmy Carter and Rev. Joseph Lowery delivered funeral orations and were critical of the Iraq War and the wiretapping of the Kings.[137][171]

King was temporarily laid in a grave on the grounds of the King Center until a permanent place next to her husband's remains could be built.[172] She had expressed to family members and others that she wanted her remains to lie next to her husband's at the King Center. On November 20, 2006, the new sarcophagus containing the bodies of the Kings was unveiled in front of friends and family. The sarcophagus is the third resting place of Martin Luther King and the second of Coretta Scott King.

Family life

Martin often called Coretta "Corrie", even when the two were still only dating.[173] The FBI captured a dispute between the couple in the middle of 1964, where the two both blamed each other for making the Civil Rights Movement even more difficult. Martin confessed in a 1965 sermon that his secretary had to remind him of his wife's birthday and the couple's wedding anniversary.[174] For a time, many accompanying her husband would usually hear Coretta argue with him in telephone conversations. King resented her husband when he failed to call her to ask about the children while he was away and when she learned of his plans to not include her in formal visits, such as the White House. However, when King failed to meet his own standards by missing a plane and fell into a level of despair, Coretta told her husband over the phone that "I believe in you, if that means anything."[175] Author Ron Ramdin wrote "King faced many new and trying moments, his refuge was home and closeness to Coretta, whose calm and soothing voice whenever she sang, gave him renewed strength. She was the rock upon which his marriage and civil rights leadership, especially at this time of crisis, was founded."[176]

After she succeeded in getting Martin Luther King Jr. Day made a federal holiday, King said her husband's dream was "for people of all religions, all socio-economic levels, and all cultures to create a world community free from violence, poverty, racism, and war so that they could live together in what he called the beloved community or his world house concept."[177]

King considered raising children in a society that discriminated against them seriously, and spoke against her husband whenever the two disagreed on the financial needs of their family.[178] The Kings had four children; Yolanda, Martin III, Dexter and Bernice. All four children later followed in their parents' footsteps as civil rights activists. Her daughter Bernice referred to her as "My favorite person".[179] Years after King's death, Bernice would say her mother "spearheaded the effort to establish the King Center in Atlanta as the official living memorial for Martin Luther King Jr., and then went on to champion a national holiday commemorating our father's birthday, and a host of other efforts; and so in many respects she paved the way and made it possible for the most hated man in America in 1968 to now being one of the most revered and loved men in the world."[180] Dexter Scott King's resigning four months after becoming president of the King Center has often been attributed to differences with his mother. Dexter's work saw a reduction of workers from 70 to 14, and also removed a child care center his mother had founded.[181] She lived in a small house with 4 children.

Lawsuits

The King family has mostly been criticized for their handling of Martin Luther King Jr.'s estate, both while Coretta was alive and after her death. The King family sued a California auction in 1992, the family's attorneys filing claims of stolen property against Superior Galleries in Los Angeles Superior Court for the document's return. The King family additionally sued the auction house for punitive damages.[182]

In 1994, USA Today paid the family $10,000 in attorney's fees and court costs and also a $1,700 licensing fee for using the "I Have a Dream" speech without permission from them.[183] CBS was sued by the King estate for copyright infringement in November 1996. The network marketed a tape containing excerpts of the "I Have a Dream" speech. CBS had filmed the speech when Martin Luther King Jr. delivered it in 1963 and did not pay the family a licensing fee.[184][185]

On April 8, 1998, King met with attorney general Janet Reno as requested by President Bill Clinton. Their meeting took place at the Justice Department four days after the thirtieth anniversary of her husband's death.[186] On July 29, 1998, Mrs. King and her son Dexter met with Justice Department officials. The following day, Associate Attorney General Raymond Fisher told reporters, "We discussed with them orally what kind of process we would follow to see if that meets their concerns. And we think it should, but they're thinking about it."[187] On October 2, 1998, the King family filed a suit against Loyd Jowers after he stated publicly he had been paid to hire an assassin to kill Martin Luther King. Mrs. King's son Dexter met with Jowers, and the family contended that the shot that killed Martin Luther King came from behind a dense bushy area behind Jim's Grill. The shooter was identified by James Earl Ray's lawyers as Earl Clark, a police officer at the time of King's death, who had been dead for several years before the trial and lawsuits emerged.[188] Jowers himself refused to identify the man he claimed killed Martin Luther King, as a favor to who he confirmed as the deceased killer with alleged ties to organized crimes.[189] The King lawsuit sought unspecified damages from Jowers and other "unknown coconspirators". On November 16, 1999, Mrs. King testified that she hoped the truth would be brought about, regarding the assassination of her husband. Mrs. King believed that while Ray might have had a role in her husband's death, she did not believe he was the one to "really, actually kill him".[190] She was the first member of the King family to testify at the trial, and noted that the family believed Ray did not act alone.[191] It was at this time that King called for President Bill Clinton to establish a national commission to investigate the assassination, as she believed "such a commission could make a major contribution to interracial healing and reconciliation in America."[192]

Legacy

Coretta was viewed during her lifetime and posthumously as having strived to preserve her husband's legacy. The King Center, which she created the year of his assassination, allowed her husband's tomb to be memorialized. King was buried with her husband after her death, on February 7, 2006. King "fought to preserve his legacy" and her construction of the King Center is said to have aided in her efforts.[193]

King has been linked and associated with Jacqueline Kennedy and Ethel Kennedy, as the three all lost their husbands to assassinations. The three were together when Coretta flew to Los Angeles after the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy to be with Ethel and shared "colorblind compassion".[194] She has also been compared to Michelle Obama, the first African-American First Lady of the United States.[195]

She is seen as being primarily responsible for the creation of the federal Martin Luther King Jr. Day. The holiday is now observed in all fifty states and has been since 2000. The first observance of the holiday after her death was commemorated with speeches, visits to the couple's tomb, and the opening of a collection of Martin Luther King Jr.'s papers. Her sister-in-law Christine King Farris said, "It is in her memory and her honor that we must carry this program on. This is as she would have it."[196]

On February 7, 2017, Republicans in the Senate voted that Senator Elizabeth Warren had violated Senate rule 19 during the debate on attorney general nominee Senator Jeff Sessions, claiming that she impugned his character when she quoted statements made about Sessions by Coretta and Senator Ted Kennedy. "Mr. Sessions has used the awesome power of his office to chill the free exercise of the vote by black citizens in the district he now seeks to serve as a federal judge. This simply cannot be allowed to happen", Coretta wrote in a 1986 letter to Senator Strom Thurmond, which Warren attempted to read on the Senate floor.[197] This action prohibited Warren from further participating in the debate on Sessions' nomination for United States Attorney General. Instead, she stepped into a nearby room and continued reading Coretta's letter while streaming live on the Internet.[198][199]

Portrayals in film

- Cicely Tyson, in the 1978 television miniseries King[200][201]

- Angela Bassett, in the 2013 television movie Betty and Coretta[202]

- Carmen Ejogo played Coretta King in both the 2001 HBO film Boycott and the 2014 film Selma.

Recognition and tributes

Coretta Scott King was the recipient of various honors and tributes both before and after her death. She received honorary degrees from many institutions, including Princeton University, Duke University, and Bates College. She was honored by both of her alma maters in 2004, receiving a Horace Mann Award from Antioch College[15] and an Outstanding Alumni Award from the New England Conservatory of Music.[203]

In 1970, the American Library Association began awarding a medal named for Coretta Scott King to outstanding African-American writers and illustrators of children's literature.[204]

In 1978, Women's Way awarded King with their first Lucretia Mott Award for showing a dedication to the advancement of women and justice similar to Lucretia Mott's.

Many individuals and organizations paid tribute to Scott King following her death, including U.S. President George W. Bush,[205] the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force,[206] the Human Rights Campaign,[207] the National Black Justice Coalition,[208] and her alma mater Antioch College.[209]

In 1983 she received the Four Freedoms Award for the Freedom of Worship.[210] She received the Key of Life award from the NAACP.[211] In 1987 she received a Candace Award for Distinguished Service from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women.[212]

In 1997, Coretta Scott King was the recipient of the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[213]

In 2004, Coretta Scott King was awarded the prestigious Gandhi Peace Prize by the Government of India.[214][215]

In 2006, the Jewish National Fund, the organization that works to plant trees in Israel, announced the creation of the Coretta Scott King forest in the Galilee region of Northern Israel, with the purpose of "perpetuating her memory of equality and peace", as well as the work of her husband.[216] When she learned about this plan, King wrote to Israel's parliament:

On April 3, 1968, the day before he was killed, Martin delivered his last public address. In it he spoke of the visit he and I made to Israel. Moreover, he spoke to us about his vision of the Promised Land, a land of justice and equality, brotherhood and peace. Martin dedicated his life to the goals of peace and unity among all peoples, and perhaps nowhere in the world is there a greater appreciation of the desirability and necessity of peace than in Israel.[citation needed]

In 2007, The Coretta Scott King Young Women's Leadership Academy (CSKYWLA) was opened in Atlanta, Georgia. At its inception, the school served girls in grade 6 with plans for expansion to grade 12 by 2014. CSKYWLA is a public school in the Atlanta Public Schools system. Among the staff and students, the acronym for the school's name, CSKYWLA (pronounced "see-skee-WAH-lah"), has been coined as a protologism to which this definition has given – "to be empowered by scholarship, non-violence, and social change." That year was also the first observance of Martin Luther King Jr. Day following her death, and she was also honored.[196]

Super Bowl XL was dedicated to King and Rosa Parks. Both were memorialized with a moment of silence during the pregame ceremonies. The children of both Parks and King then helped Tom Brady with the ceremonial coin toss. In addition two choirs representing the states of Georgia (King's home state) and Alabama (Park's home state) accompanied Dr. John, Aretha Franklin and Aaron Neville in the singing of the National Anthem.[217]

She was inducted into the Alabama Women's Hall of Fame in 2009.[218] She was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 2011.[219]

In January 2023, The Embrace was unveiled in Boston;[220] this sculpture commemorates Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King,[221][222] and depicts four intertwined arms,[223] representing the hug they shared after he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.[224]

Congressional resolutions

Upon the news of her death, moments of reflection, remembrance, and mourning began around the world. In the United States Senate, Majority Leader Bill Frist presented Senate Resolution 362 on behalf of all U.S. Senators, with the afternoon hours filled with respectful tributes throughout the U.S. Capitol.[citation needed]

On August 31, 2006, following a moment of silence in memoriam of the death of Coretta Scott King, the United States House of Representatives presented House Resolution 655 in honor of her legacy. In an unusual action, the resolution included a grace period of five days in which further comments could be added to it.[225][226]

See also

References

- ^ Jump up to: a b "JFK's famous phone call to Coretta Scott King". NBC News. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ "Coretta Scott King honored at church where husband preached". Lodi News-Sentinel. February 6, 2006. Archived from the original on May 15, 2016.

- ^ Waxman, Laura Hamilton (January 2008). "Coretta Scott King". Lerner Publications. ISBN 9780761340003. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Schraff, Anne E. (1997). Coretta Scott King: striving for civil rights. Enslow Publishers. p. 14. ISBN 0894908111. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Bruns, Roger (2006). Martin Luther King, Jr: A Biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 25. ISBN 0313336865. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

Bernice McMurray Scott indian.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bagley, Edyth Scott (2012). Desert Rose: The Life and Legacy of Coretta Scott King. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-0-8173-1765-2. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ King, Coretta Scott and Rev. Dr. Barbara Reynolds (January 17, 2017). My Life, My Love, My Legacy. Henry Holt and Company. p. 11. ISBN 9781627795999.

- ^ Gelfand, p. 17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Coretta Scott King". Women's History. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008.

- ^ Octavia B. Vivian (April 30, 2006). Coretta: The Story of Coretta Scott King. Fortress Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8006-3855-9. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

coretta scott king family owned farm since civil war.

- ^ Gelfand, p. 15.

- ^ "Coretta Scott King: My Childhood as a Tomboy / Growing into a Lady". Visionaryproject. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ^ "Coretta King". Ebony. November 1968. Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Bagley, p. 7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c King, Coretta Scott (Fall 2004). "Address, Antioch Reunion 2004". The Antiochian. Archived from the original on May 1, 2007. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- ^ Bagley, p. 62.

- ^ Bagley, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Bagley, p. 67.

- ^ Bagley, p. 58.

- ^ Lithgow, John (August 24, 2017). "Upfront / What I Know Now: John Lithgow". AARP the Magazine. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ "Coretta Scott King Dies at 78". ABC News. January 31, 2006. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- ^ Fleming, p. 16.

- ^ Dyson, p. 212.

- ^ Bagley, pp. 96–98.

- ^ Garrow, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Bagley, p. 96.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bagley, p. 99.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Branch, p. 98.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bagley, p. 100.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fleming, p. 17.

- ^ "Never Again Where He Was". Time. January 3, 1964. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- ^ Mallard, Aida. "King Commission, AKA sorority pay tribute to Coretta Scott King". The Gainesville Sun. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- ^ "Coretta Scott King Biography and Interview". American Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on August 18, 2019. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- ^ Nazel, p. 69.

- ^ Bagley, p. 108.

- ^ Bagley, p. 111.

- ^ Bagley, p. 125.

- ^ Bagley, p. 144.

- ^ Garrow, p. 83.

- ^ Bagley, p. 124.

- ^ Garrow, p. 65.

- ^ Bagley, p. 150.

- ^ Darby, p. 47.

- ^ McPherson, p. 46.

- ^ "India Trip (1959)". Archived from the original on December 11, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ Darby, p. 51.

- ^ Garrow, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Burns, p. 134.

- ^ Gibson Robinson, p. 131.

- ^ Garrow, p. 61.

- ^ Vivian, p. 20.

- ^ O'Brien, p. 485.

- ^ Goduti, p. 39.

- ^ Matthews, p. 171.

- ^ Bagley, p. 192.

- ^ McCarty, p. xiii.

- ^ McPherson, p. 56.

- ^ Mahoney, p. 247

- ^ Jump up to: a b Branch, p. 736.

- ^ Fairclough, p. 77.

- ^ Schlesinger, p. 328.

- ^ Willis, p. 166.

- ^ McPherson, p. 57.

- ^ Bagley, p. 181.

- ^ (Gentry, pg. 572–573.)

- ^ Gentry, p. 572.

- ^ Gentry, p. 575.

- ^ Dyson, p. 217.

- ^ "The FBI's Ugly Obsession With Dr. Martin Luther King Jr". Amanpour & Company. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Robinson, Tom (2014). Malcolm X: Rights Activist and Nation of Islam Leader. Abdo. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-61783-893-4. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ^ Bagley, p. 30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Crosby, Emilye (2011). Civil Rights History from the Ground Up: Local Struggles, a National Movement. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820338651. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- ^ Bagley, p. 213.

- ^ "Jacqueline Kennedy on Rev. Martin Luther King Jr". ABC News. September 8, 2011. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ^ Rickford, Russell J. (2003). Betty Shabazz: A Remarkable Story of Survival and Faith Before and After Malcolm X. Naperville, Illinois: Sourcebooks. p. 349. ISBN 1-4022-0171-0. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ^ Clarke, p. 124.

- ^ Blake, John (August 25, 2013). "Moving out of the dreamer's shadow: A King daughter's long journey". CNN. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gelfand, p. 7.

- ^ Heymann, p. 149.

- ^ Schlesinger, p. 876.

- ^ Burns, p. 75.

- ^ Black, p. 523.

- ^ Burns, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Loh, Jules (April 18, 1968). "Coretta King Expected to Take Active Role in Crusade". The Free Lance–Star. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Oppenheimer, p. 417.

- ^ Burns, p. 129.

- ^ Gelfand, p. 12.

- ^ "Widow Hopes For Fulfillment of King's Dream". Jet. April 18, 1968. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Gelfand, p. 13.

- ^ Josephine Baker and Joe Bouillon, Josephine. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1977.

- ^ Pappas, Heather. "Coretta Scott King". Nuclear Age Peace Foundation. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- ^ Crosby, p. 402.

- ^ "When widowhood speaks to black civil rights: Coretta Scott King". Women News Network. January 20, 2014. Archived from the original on January 25, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ Oppenheimer, p. 458.

- ^ "Accused Slayer of Dr. Martin Luther King Arrested". Star–Banner. June 9, 1968. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "Coretta Scott King". CBS News. January 16, 2012. Archived from the original on March 3, 2018. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ Bagley, p. 256.

- ^ Dexter King Will Succeed Mom Coretta Scott King as Chairman/CEO MLK Center. Johnson Publishing Company. November 7, 1994. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Nixon papers reveal Elvis's rip of Beatles". Chicago Sun-Times. December 2, 1986. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014.

- ^ Karnow p.599.

- ^ "FBI spied on Coretta Scott King, files show". Los Angeles Times. August 31, 2007. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved September 11, 2007.

- ^ "FBI Files Reveal Government Spied on Coretta Scott King". Jet. September 24, 2007. Archived from the original on January 6, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "Coretta Scott Still Working To Have Husband's Birthday Declared Holiday". The Gadsden Times. January 14, 1972. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Gentry, p. 34.

- ^ "Coretta defends Young". Deseret News. July 26, 1978.

- ^ Polden, p. 112.

- ^ "Ted Turner hires Coretta King". Star-News. September 30, 1980.

- ^ "Coretta King says Jackson can't win". The Register-Guard. August 26, 1983. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Miller, Laurel E. (June 27, 1985). "Coretta King Arrested at Embassy". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 15, 2013. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ "Reagan offers Coretta King an apology". Lawrence Journal-World. October 22, 1983. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "Coretta Scott King satisfied with Reagan's apology". Nevada Daily Mail. October 23, 1983. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Byrd, Robert (February 11, 1987). "Coretta King outraged at jailing of 'Winfrey Show' protestors". The Lewiston Journal.

- ^ Smith, Shawn Maree (March 9, 1989). "Coretta Scott King Sidesteps Controversy on Convention Center". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 8, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Coretta Scott King Outraged About Strike". Orlando Sentinel. January 18, 1993. Archived from the original on January 12, 2014. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ^ Ostrow, Ronald J. (February 17, 1993). "Coretta King, at FBI Headquarters, Backs Sessions, Assails Hoover". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 8, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ Howard, Scripps (February 17, 1993). "Coretta Scott King Praises Sessions, FBI". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ "Opposition to Violence, Assault Weapons Are Focus of King Day". Los Angeles Times. January 18, 1994. Archived from the original on January 8, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Coretta King: Charges Aim To Smear Malcolm X". Orlando Sentinel. February 2, 1995. Archived from the original on January 12, 2014. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ^ Rickford, p. 483.

- ^ "Coretta King Discusses Verdicts". Los Angeles Times. October 13, 1995. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- ^ Thomas, Jerry (January 25, 1996). "Coretta Scott King Carries Dream". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ^ "Shabazz Fund Drive Gets Levin, King Donations". Orlando Sentinel. June 18, 1997. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ "King's widow victim of multiple burglaries". Kentucky New Era. January 14, 2005. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "King's widow moves to condo from family home after multiple burglaries, son says". Sioux City Journal. January 14, 2005. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ Chu, Louise (January 14, 2005). "King's widow victim of multiple burglaries". Kentucky New Era. Retrieved December 28, 2020 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ Baird, Woody (December 10, 1999). "King family gets jury verdict on conspiracy". Ellensburg Daily Record.

- ^ "Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Family Commemorate 32nd Anniversary of His Death". Jet. April 24, 2000. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "Andrew Young Remembers Coretta Scott King". NPR.org. NPR. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ "A King among men: Martin Luther King Jr.'s son blazes his own trail – Dexter Scott King". Vegetarian Times. 1995.

- ^ Reynolds, Barbara A. (February 4, 2006). "The Real Coretta Scott King". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 6, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ "Mrs. King warns of sanctions 'hardship'". Chicago Sun-Times. September 13, 1986. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014.

- ^ "Mrs. King won't meet Botha". Chicago Sun-Times. September 10, 1986. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014.

- ^ "Key apartheid foe meets King, hails her 'courage'". Chicago Sun-Times. September 11, 1986. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014.

- ^ "King meets Winnie Mandela, denies snub to Botha // Emotions run high for apartheid foes". Chicago Sun-Times. September 12, 1986. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014.

- ^ Dyson, Michael Eric; Jagerman, David L. (2000). I May Not Get There with You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr – Michael Eric Dyson. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780684867762. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved May 13, 2015.