1721 Boston smallpox outbreak

| 1721 Boston smallpox epidemic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Disease | Smallpox |

| Virus strain | Variola major |

| Location | Boston, Massachusetts |

| Index case | British sailor disembarking HMS Seahorse [1][2] |

| Dates | 22 April 1721 - 22 February 1722 |

| Confirmed cases | 5,759 [3] |

Deaths | 844 [4][3] |

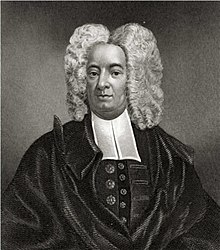

In 1721, Boston experienced its worst outbreak of smallpox (also known as variola). 5,759 people out of around 10,600[5] in Boston were infected and 844 were recorded to have died between April 1721 and February 1722.[4][3] The outbreak motivated Puritan minister Cotton Mather and physician Zabdiel Boylston to variolate hundreds of Bostonians as part of the Thirteen Colonies' earliest experiment with public inoculation. Their efforts would inspire further research for immunizing people from smallpox, placing the Massachusetts Bay Colony at the epicenter of the Colonies' first inoculation debate and changing Western society's medical treatment of the disease. The outbreak also altered social and religious public discourse about disease, as Boston's newspapers published various pamphlets opposing and supporting the inoculation efforts.

Smallpox in Boston

[edit]

On 22 April 1721 the British passenger ship HMS Seahorse arrived at Boston from Barbados,[6] after one stop at Tortuga,[7] with a crew of sailors who had just survived smallpox.[2] Customs' quarantine hospital at Spectacle Island was tasked with containing individuals who had contagious diseases, with a case of smallpox contained successfully the previous fall.[2] But one of Seahorse's sailors fell ill in Boston Harbor a day after arrival, and exposed other sailors to variola.[8] Boston's water bailiff inspected Seahorse and discovered another two or three cases of smallpox in various stages before ordering the ship to leave the harbor. Despite the sailor being hurriedly quarantined in the lodging house where he fell ill, nine other sailors at Boston Harbor exposed to him came down with smallpox in early May.[8] The sailors were quarantined on Spectacle Island's very-rudimentary hospital but staff and customs were unable to contain the virus.[9] On 26 May Cotton Mather wrote in his diary: "The grievous calamity of the small pox has now entered the town."[6]

Boston's last smallpox outbreak had been in 1703, and a new generation of non-immune children and young adults was vulnerable. By June the town was faced with a major public health crisis and the religious public became increasingly worried that they were the subjects of divine punishment.[10] Around 900 people fled Boston into the countryside,[11] likely spreading the virus. The General Court, colonial Massachusetts' legislating body, moved from Boston to Cambridge at summer's end, but smallpox cases began appearing in Cambridge in August.[10] James Franklin's The New England Courant was founded in August amid the outbreak and the issue of smallpox and preservation from it became front page news.[5] The Courant was ordered in early October by the town council to publish a house-by-house count on those affected so far by smallpox: 2,757 cases, 1,499 recoveries and 203 deaths were counted.[12] The outbreak peaked in October when 411 people died in that month alone.[12] Judge Samuel Sewall recorded in his diary the deaths of his friends and neighbors like one Madam Checkly on 18 October.[9] Thanksgiving sermons were also affected by the outbreak, and on 26 October most congregations held a single sermon at 11 in the morning out of fear of smallpox spreading during gatherings. The next day Judge Sewell attended the funeral of local child Edward Rawson before attending the burial of one of Sewell's own tenants, while a local college student and "many others" were buried that Friday night.[9] 8% of Boston's population would die during the epidemic,[7] and hundreds of other Bostonians would recover with severe scarring or disabilities.

Public inoculation campaign

[edit]

Cotton Mather sent letters to Boston's 14 other physicians regarding the outbreak[1] imploring them to wage a medical campaign against smallpox by inoculating their own patients or volunteers. Mather had been interested in inoculation since 1715 when a slave named Onesimus informed Mather about a procedure in Africa which made him immune to smallpox for life. The scars were commonly found on enslaved people kidnapped from Africa, and valued by slave traders.[13] Mather read physician Emmanuel Timoni's description of a similar procedure witnessed while serving Great Britain's ambassador in Turkey.[14][5] The procedure Timoni called inoculation involved drying pus from a smallpox patient and rubbing or scraping it into a healthy person's skin, giving them a mild case of pox that conferred lifetime immunity.[15] Mather wanted to prove variolation was a relatively safe and effective procedure to protect people against smallpox. Many physicians, however, feared the possibility of smallpox fatally spreading and the social implications of deliberately infecting others.[16]

Zabdiel Boylston of Harvard University was the only doctor who positively responded to Mather, beginning America's first public campaign of inoculation. On 26 June 1721, Boylston first inoculated his six-year-old son Thomas, and then his 36-year-old slave and the slave's two-year-old son.[17] To the doctor's relief, all survived relatively mild cases of smallpox without disability or disfigurement. Boylston then felt confident enough about the procedure's safety, and over a period of five months during the outbreak[5] inoculated 247 people in and around Boston (with 6 fatalities).[8] Among them was Cotton Mather's son Samuel, whose chambermaid contracted smallpox at Harvard. On the 25 November 1721, Boylston inoculated 15 individuals at Harvard: thirteen students, professor Edward Wiglesworth, and tutor William Welsted.[10] They all survived, leaving the university's student body and faculty fascinated by the procedure. Cotton Mather writes in a letter detailing Dr. Boylston's work in Boston: "The experiment has now been made on several hundred persons, upon both male and female, upon both old and young, upon both strong and weak, upon both white and black."[17]

Boylston was unable to continue his inoculation campaign beyond November due to opposition from Boston's Selectmen restricting him, as well as occasional violence from the public. But a tutor at Harvard inspired by his research, Thomas Robie, continued vaccinating patients at Spectacle Island. One of his patients was another tutor, Nicholas Sevier, who returned to Harvard sixteen days after he was inoculated to report on the success of his procedure. Harvard's academic community became more accepting of inoculation after the successful experiments of Boylston and Nicholas Sevier.[10]

Inoculation controversy and violence

[edit]

Cotton Mather believed inoculation was a divine gift to protect people from smallpox[17][5] and Boylston felt duty-bound as a physician to protect his children and others from smallpox.[4] Many contemporary Bostonians, however, were terrified of smallpox spreading from inoculated patients [18][3] and outraged at the idea of deliberately infecting people. Inoculation also evoked anger from dubious physicians. One such physician, William Douglass, was a vehement inoculation opponent who published anti-inoculation pamphlets in response to Mather's experiment. One pamphlet published in The New England Courant read "Some have been carrying about instruments of inoculation, and bottles of poisonous humor, to infect all who were willing to submit to it. Can any man infect a family in the morning, and pray to God in the evening that the distemper will not spread?" [3] Douglass believed only accredited medical professionals like himself should conduct such dangerous procedures,[5] while he personally opposed inoculation. Boylston was ridiculed and satirized in the newspapers, portrayed as a quack by Douglass and other physicians.[3]

Variolation still did present a risk of death for 2% of those having the procedure. This was fertile ground for criticism. Furious rumors swirled around inoculation as The New England Courant published Douglass and Dalhonde's sensationalist articles against inoculation.[3] One article by Douglass darkly joked about using inoculations against surrounding Native American communities.[5] Dr. Boylston became notorious and the colonial government remained deeply skeptical of his and Mather's experiment. The Boston City Council summoned him in early August to explain his procedures, and the Council condemned inoculation and ordered him to desist immediately. Despite the opposition, Boylston garnered support of local learned men like Cotton's father Increase Mather and four other "inoculation ministers" by the names of Benjamin Coleman, Thomas Prince, John Webb, and William Cooper. Inoculations resumed two days later.[2] Dr. Boylston was assaulted in the streets for this[5] and eventually threatened to the point he secretly hid in his house for two weeks.

Cotton Mather was also terrorized by an angry public as rumors spread wildly about inoculations. Mobs eventually began forcing the variolated into isolation at Spectacle Island's quarantine house.[10] Cotton Mather inoculated his nephew, Reverend Walter, and offered to let him stay at Mather's home while he recovered from smallpox, but a fearful mob became aware and attacked and threw a crude bomb directly into the room where Walter was staying.[4] The device failed to explode, but a note tied to it read "Cotton Mather, I was once of your meeting, but the cursed lye you told of - you know who, made me leave you, you dog, and damn you, I will inoculate you with this, with a pox on you!"[4]

A prominent member of Boston's clergy to oppose inoculation was John Williams. Williams criticized variolation as sinful and "not in the Rules of Natural Physick." Cotton Mather countered that to reject inoculation would be a violation of the Bible's 6th Commandment since many people would die.[5]

Social and scientific impact

[edit]

The outbreak was the first time in American medicine where the press was used to inform (or alarm) the general public about a health crisis.[1] The New England Courant, under the leadership of its new editor 16 year-old Benjamin Franklin, continued to publish satirical articles about the Mather and inoculation in the months following the epidemic.[7] Boylston wrote an account of his experiences with inoculation in An Historical Account of the Small Pox Inoculated in New England. Most of Boston's clergy seemed to have supported inoculation, and some wrote an op-ed opposing Williams and Douglass's criticism: "tho [Dr. Boylston] has not had... an Academic Education, and congruently not the Letters of some Physicians in town, yet he ought by no means be called Illiterate, Ignorant, etc. Would the town bear that Dr. Cutter or Dr. Davis be so treated?" Minister Benjamin Coleman, believing in inoculation, collected inoculation stories from slaves similar to Onesimus's account and published "Some observations on the new method of receiving the small pox by ingrafting or inoculation" in opposition to Douglass.[5]

Boston's smallpox outbreak of 1721 is unique for motivating America's first public inoculation campaign, and the controversy that surrounded it. On 22 February 1722, it was officially announced that no new cases of smallpox were appearing in Boston and the disease was in decline.[1] In the outbreak's aftermath, with over 800 Bostonians dead and many more disfigured from smallpox, Boylston's 247 inoculated patients had a 2% death rate versus the 15%[8][5] of people who died if they got smallpox naturally.[2] Boylston's successful experiments on students and faculty at Harvard led to early acceptance in Boston's powerful academic community for the procedure.[10] After Mather and Boylston's highly-publicized experiments with inoculation, and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu's similar experiments during a simultaneous outbreak in London, variolation would become a widespread and well-researched technique in the West decades before Edward Jenner's discovery of vaccination with cowpox. In 1723, Boylston traveled to England and received honors by King George. In London he published an account of his work, An Historical Account of the Smallpox Inoculated in New England.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Farmer, Laurence (1958). "The Smallpox Inoculation Controversy and the Boston Press 1721-2". Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 34 (9). New York, NY: 599–601, 608. PMC 1805980. PMID 13573028.

- ^ a b c d e Coss, Stephen (2016-03-08). The Fever of 1721. Simon & Schuster. pp. iii–ix, 5, 119. ISBN 9781476783086. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Thatcher, M.D., James (1828). American Medical Biography, Or, Memoirs of Eminent Physicians who Have Flourished in America. To which is Prefixed a Succinct History of Medical Science in the United States, from the First Settlement of the Country. Richardson & Lord and Cottons & Barnard. pp. 27, 189. ISBN 978-0-608-39804-4. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Kelly, M.D., Howard; Burrage, M.D., Walter (1920). American Medical Biographies. The Norman, Remington Company. p. 134. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "To Inoculate or Not to Inoculate?: The Debate and the Smallpox Epidemic of Boston in 1721". Constructing the Past. 1 (1). Illinois Wesleyan University: 62–66. 2000. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ a b Flower, Darren (2008-10-13). Bioinformatics for Vaccinology. Edward Jenner Institute for Vaccine Research, Berkshire, UK: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9780470699829. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ a b c Schwartz, Frederick (November 1996). "1721". American Heritage. 47 (7).

- ^ a b c d Best, M.; Neuhauser, D.; Slavin, L. (2004). ""Cotton Mather, you dog, damn you! I'll inoculate you with this; with a pox to you": smallpox inoculation, Boston, 1721". Quality & Safety in Health Care. 13 (1). Qual Saf Health Care: 82–83. doi:10.1136/qshc.2003.008797. PMC 1758062. PMID 14757807.

- ^ a b c "Samuel Sewall and the 1721 Boston Smallpox Epidemic". William and Mary Quarterly. The New England Historical Society. 2014-10-07. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Burton, John (September 2001). ""The Awful Judgements of God upon the Land": Smallpox in Colonial Cambridge, Massachusetts". The New England Quarterly. 74 (3): 495–506. doi:10.2307/3185429. JSTOR 3185429.

- ^ Creighton, Charles (1894). A History of Epidemics in Britain. Vol. 2. Cambridge: The University Press. pp. 46–47. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ a b "The Pamphlet Wars over Smallpox Vaccination, 1721" (PDF). National Humanities Society. Early America Imprints online. 2009. p. 4. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ How an African slave helped Boston fight smallpox

- ^ Behbehani, Abbas (December 1983). "The Smallpox Story: Life and Death of an Old Disease". American Society for Microbiology. 47 (4): 464. doi:10.1128/mr.47.4.455-509.1983. PMC 281588. PMID 6319980.

- ^ Aehlbach, Stephen (2016). American Plagues: Lessons from our Battles with Disease. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 25–27. ISBN 9781442256514. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Grant, Alicia (2019-05-03). Globalisation Of Variolation: The Overlooked Origins Of Immunity For Smallpox In The 18th Century. World Scientific. pp. 228–233. ISBN 978-1-78634-586-8.

- ^ a b c Minardi, Margo (January 2004). "The Boston Inoculation Controversy of 1721-1722: An Incident in the History of Race". The William and Mary Quarterly. 61 (1). Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture: 57–82. doi:10.2307/3491675. JSTOR 3491675.

- ^ Smallpox: Deadly Again? (video). History Channel. 31 January 2000. Event occurs at 18:02. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Best, M; Katamba, A; Neuhauser, D (2007-12-01). "Making the right decision: Benjamin Franklin's son dies of smallpox in 1736". Quality and Safety in Health Care. 16 (6): 478–480. doi:10.1136/qshc.2007.023465. ISSN 1475-3898. PMC 2653186. PMID 18055894.