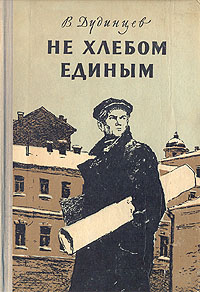

Not by Bread Alone

Not by Bread Alone (Russian: Не хлебом единым) is a 1956 novel by the Soviet author Vladimir Dudintsev. The novel, published in installments in the journal Novy Mir, was a sensation in the USSR. The tale of an engineer who is opposed by bureaucrats in seeking to implement his invention came to be a literary symbol of the Khrushchev Thaw.

Plot

[edit]References

[edit]"Bread" formed part of one of the most important political slogans of the Bolshevik Revolution: "Bread, Land, Peace and All Power to the Soviets."[citation needed]

However, "Not by bread alone" is a quote which appears once in the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) and twice in the Christian Scriptures (New Testament) and reads in the King James Version as follows:

- But he answered and said, It is written, Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of God. (Matthew 4:4, quoting Deuteronomy 8:3)

- And Jesus answered him, saying, It is written, Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word of God. (Luke 4:4)

The title may also refer in part to To Make My Bread by American writer Grace Lumpkin; the book won the Maxim Gorky Prize for Literature in 1932.

Summary

[edit]Late in the Joseph Stalin era, a teacher of physics, Dimitri Lopatkin, invents a machine which revolutionizes the centrifugal casting of pipes, then a difficult and time-consuming operation. Lopatkin, a loyal communist, believes his invention will help the Soviet economy if it is used. Despite the machine's merits, it is rejected by bureaucrats. When Lopatkin gets a chance to have a demonstration model built at a Moscow institute, his opponents favor a rival machine and then cancel Lopatkin's. Lopatkin is offered a chance to work on his machine for the military, which he accepts, but he is soon arrested and accused of passing secrets to his lover, Nadia Drozdova, the estranged wife of one of the officials who opposes him.

At trial, Lopatkin asks what secrets he is accused of betraying, and the judges respond that he is not allowed to know that; the identity of the secrets is itself secret. One of the judges, a young major named Badyin, sees the absurdity of the proceedings and defends Lopatkin. Nonetheless, the inventor is convicted and sentenced to eight years in a labor camp, with Badyin announcing he will write a dissenting opinion. While Lopatkin gains permission to have his papers turned over to Nadia, the papers are believed to be destroyed.

A year and a half later, Lopatkin's case is reviewed, and he is released and returns. He finds that Nadia has been able to obtain his papers, that the designers who built the demonstration model have been able to replicate it, and that his machine is in operation in a factory in the Urals. An investigation is ordered into the officials who blocked Lopatkin, but they get off lightly and are later promoted.

Lopatkin is now a respected inventor, earning a fine living. The officials, who form an invisible web that frustrate the individualists, suggest that he should buy a car, a television, or a dacha, and by implication become like them, but Lopatkin says, no, he will continue to fight them: "Man lives not by bread alone, if he is honest." Lopatkin realizes he will spend his life fighting the bureaucrats.

Impact

[edit]Soviet reaction and aftermath

[edit]Initially, official reaction, as expressed in Pravda and other periodicals, reflected reserved praise for Dudintsev's book. Toward the end of 1956, official organs began to attack the author and his book. However, this did not change the position of the readers, who continued to praise the novel and compared its detractors to the less savory characters in it.[1]

Communist Party First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev praised the powerful imagery of some of the pages but stated that the novel was "false at its base".[2] Khrushchev also complained that Dudintsev had "biasedly scissored out negative facts for tendentious presentation from an unfriendly angle."[3] Others joined in: Dudintsev was accused of vilifying Soviet society and his book of being a social evil. His works rapidly became untouchable, and he sank into poverty.[4] Not by Bread Alone was reprinted in the 1960s, after Khrushchev's fall, but this was seen as more a way of denigrating the former leader than honoring the author.[4] The book was published in English in 1957, and The New York Times praised it for its insights into Soviet life.[3]

While the book was republished in 1968, 1979, and again during perestroika, it did not again spark such a reaction. Readers viewed Not by Bread Alone as obsolete once more explicit books about the terror, such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, were published. One reader wrote to Solzhenitsyn, "We still have fresh memories of the attacks on V. Dudintsev for his Not by Bread Alone—which, compared to your story, is merely a children's fairy tale."[5]

Public reception in Russia

[edit]The public gave the novel an overwhelmingly positive reception. The issues of Novy Mir containing the novel sold out within hours. Subscribers to the journal were besieged with demand for their copies. Readers waited months to be allowed to borrow a copy from a library.[6] The laws of supply and demand took over in the Soviet Union, and copies could be obtained on the secondary market for five times the cover price.[7] At a time when intense reaction to a literary work would last not more than a couple of months, Novy Mir received hundreds of letters, the flood continuing as late as 1960.[8] One enthusiastic response came from a KGB office in Latvia.[9] One schoolteacher from Belarus wrote to the author:

At last, literature has begun talking about our painful problems, about something that hurts and has become, unfortunately, a typical phenomenon of our life! At last a writer has appeared who saw predatory beasts enter our life, rally together, and stand like a wall in the way of everything honest, advanced, and beautiful![9]

Public reception abroad

[edit]Former American communist spy and writer Whittaker Chambers wrote in the late 1950s—clearly influenced by the book: "A civilization which supposes that what it chiefly has to offer mankind is more abundant bread—that civilization is already half-dead. Sooner or later it will know it as it chokes on a satiety of that bread by which alone men cannot live."[10] (Chambers was also personal friends with Grace Lumpkin, author of To Make My Bread (1932).[citation needed])

2005 movie

[edit]In 2005, Mosfilm director Stanislav Govorukhin released the movie, Not by Bread Alone based on the novel. The advertising campaign for the movie coincided with the 2005 State Duma by-elections there, and Govorukhin was a candidate from the governing United Russia party. His main opponent, writer Victor Shenderovich, complained that the advertisements for the film constituted illegal political advertisements for Govorukhin, but the complaints were not accepted by the court.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ Kozlov 2006, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Taubman 2003, p. 308.

- ^ a b Burger, Nash (1957-10-21), "Books of the Times", The New York Times, retrieved 2009-09-09 (fee for article)

- ^ a b Wines, Michael (1998-07-30), "Vladimir Dudintsev, 79, dies; writer dissected Soviet life", The New York Times, retrieved 2009-09-09 (fee for article)

- ^ Kozlov 2006, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Kozlov 2006, p. 80.

- ^ Whitney, Thomas (1957-03-24), "The novel that upsets the Kremlin", The New York Times, retrieved 2009-09-09 (fee for article)

- ^ Kozlov 2006, p. 82.

- ^ a b Kozlov 2006, p. 83.

- ^ Chambers, Whittaker (1964). Cold Friday. Random House. pp. 14=15.

Bibliography

[edit]- Kozlov, Denis (2006). "Naming the Social Evil: The Readers of Novyi mir and Vladimir Dudintsev's Not by Bread Alone, 1956-59 and beyond". The Dilemmas of De-Stalinization: Negotiating Cultural and Social Change in the Khrushchev Era, Edited by Polly Jones. Routledge: 80–98. ISBN 0-415-34514-6.

- Taubman, William (2003). Khrushchev: The Man and His Era. W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-32484-2.

External links

[edit]- Not By Bread Alone, 1957 English translation of book in PDF format

- Not by Bread Alone on Lib.ru electronic library (in Russian)

- Not by Bread Alone at IMDb

- Not By Bread Alone A detailed summary of the novel from SovLit.net