Nutrition education

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (July 2019) |

Nutrition education is a combination of learning experiences designed to teach individuals or groups about the principles of a balanced diet, the importance of various nutrients, how to make healthy food choices, and how both dietary and exercise habits can affect overall well-being.[1] It includes a combination of educational strategies, accompanied by environmental supports, designed to facilitate voluntary adoption of food choices and other nutrition-related behaviors conducive to well-being.[2] Nutrition education is delivered through multiple venues and involves activities at the individual, community, and policy levels. Nutrition Education also critically looks at issues such as food security, food literacy, and food sustainability.[2]

Overview

[edit]Nutrition education promotes healthy-eating and exercise behaviors.[3] The work of nutrition educators takes place in colleges, universities and schools, government agencies, cooperative extension, communications and public relations firms, the food industry, voluntary and service organizations and with other reliable places of nutrition and health education information.[2] Nutrition education is a mechanism to enhance awareness,[3] as a means to self-efficacy, surrounding the trigger of healthy behaviors.[4]

Stages of Nutrition Education

[edit]There are generally three main phases of nutrition education: a motivational phase, an action phase, and an environmental component.[2]

In the motivational stage, the goal is to increase awareness and improve the motivation of the audience to choose good nutrition habits. Individuals focus on why they should make changes to their diets. This stage aims to help the audience recognize the benefits of making healthier choices and the potential risks of not taking action.

In the action phase, the goal is to promote the ability to act on the motivations to make healthier choices. Individuals focus on how to make changes. This component consists of helping individuals bridge the gap between an intention and action. Here people make goals and specific action plants in order to foster this change.

Finally, in the environmental component, nutrition educators and policymakers work together to create and promote better environmental support on the community, regional, and national levels. The goal of this environmental change is to make healthier foods more accessible to a wider population in order to increase the opportunities and likelihood for individuals to make healthy choices.

Nutrition Education in the United States

[edit]National Education and Training (NET) program

[edit]In 1969, a recommendation from the White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health stated that nutrition education should be part of school curriculums.[5] It was authorized under the Children Nutrition Act. In 1978, the Nutrition Education and Training (NET) program was created by the USDA, with the purpose of giving grants to help fund nutrition education programs under state educational systems.[5] Funding for the program was targeted towards school children, teachers, parents, and service workers.[6] In its inaugural year, the program was funded with $26 million gradually decreasing to $5 million in 1990.[5] In 1996, NET was restored to temporary status.[7]

Current government oversight

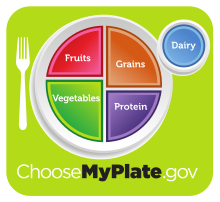

[edit]The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is tasked with providing nutrition education and establishing dietary guidelines based on current scientific literature.[8] Through many of their programs, children and low-income citizens can access food that otherwise would be unavailable.[8] Two agencies within the USDA that deal with nutrition education are the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) and the Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion (CNPP).[9] The main objectives of the Food and Nutrition Service are to help reduce the risk of obesity and ensure that hunger is no longer a concern for US citizens through a variety of assistance programs.[9] Some of the programs of the FNS include WIC, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and school meals.[9] The CNPP is responsible for developing dietary guidelines based on scientific evidence and promoting them to consumers through nutrition programs such as MyPlate.[10] Nutrition education complements the USDA's assistance programs and is administered by the FNS. This federally funded nutrition education is based on the guidelines developed by the CNPP.[11]

In addition, the USDA also administers the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP) through the National Institute of Food and Agriculture.[11] This program focuses on reaching those in low-income households to address health disparities associated with prevalent societal challenges such as hunger, malnutrition, poverty, and obesity. EFNEP aims to help low-income families improve their nutritional well-being through interactive lessons in a holistic nutrition education approach.[12] The four core content areas within the EFNEP are Diet Quality and Physical Activity, Food Resource Management, Food Safety, and Food Security.[12]

Legislation

[edit]The Improving Child Nutrition and Education Act of 2016 was a bill introduced in the United States Congress aimed at enhancing child nutrition programs and education.[13] The key provisions of the bill included expanding access to school meal programs, promoting nutrition education, streamlining administrative processes, and addressing food waste. Overall, the bill sought to improve the health and well-being of children by ensuring they have access to nutritious meals and education about healthy eating habits. [1]

The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 passed by the Obama administration in 2010 included provisions that led to reforms that established minimum requirements that all food and beverages sold on schools' campuses must meet.[14] The new standards include limits on the amount of sugar, sodium, and calories from saturated fat that specific foods may contain per item.[14]

The Public Health Service Act was enacted in 1944 and broadened the scope of the Public Health Service functions.[15] IMPACT (The Improved Nutrition and Physical Activity Act) was a piece of legislation introduced in the Senate in 2005 aimed to amend the Public Health Service Act in reducing obesity among children.[16] It called for a grants to include the identification, treatment, and prevention of eating disorders and obesity.[17]

Examples of government agencies that incorporate nutrition education into their programs, include

[edit]- Let's Move, launched by First Lady Michelle Obama in February 2010, this program is a comprehensive learning approach that brings in the all aspects of child health, through the Healthier US School Challenge;[18]

- USDA Food and Nutrition Service, which provides nutrition education materials to children and adults of all ages and nutrition education to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) participants and applicants;

- USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture through the cooperative extension program Archived 2013-06-12 at the Wayback Machine; and

- MyPyramid.gov, through the Ten Tips Nutrition Education Series.

- MyPlate, a program started through the FDA that helps come up with a personalized diet depending on your age, height, weight, sex, and physical activity.[19]

In school

[edit]K-12

[edit]Nutrition education programs within schools try to create behaviors that prevent students from potentially becoming obese, developing diabetes and cardiovascular issues, and forming negative emotional issues by educating students on the aspects of a healthy diet, emphasizing the consumption of lower fat dairy options and both fruits and vegetables.[21] Studies support that good nutrition significant contributes to the well-being of children and their learning ability, thus leading to better school performance.[3] As most children eat between one and two of their meals at school, school-based nutrition education programs offer opportunities for students to practice making healthy eating decisions.[21] However, due to influences outside of the school environment such as home, cultural, and social environments, there may be a lack of visible desired behavior changes.[21] The National Center for Health Statistics October 2017 data brief, found that the prevalence of obesity among youth ages 2–19 has increased from 13.9 to 18.5 percent from 1999 to 2016.[22]

College

[edit]With eating behaviors, such as missing meals throughout the day and engaging in potentially dangerous self-prescribed weight loss methods, combined with a diet consisting of foods high in sodium, cholesterol and saturated fats, college students' dietary habits can potentially negatively affect their current and future health.[23] A typical college student's diet does not contain enough vitamins, minerals or fiber.[23] Limited in both the consumption of fruit and vegetables, research has shown that enrollment in a university nutrition class, emphasizing the consumption of fruits and vegetables and certain dietary habits that prevent chronic disease, significantly increased the students consumption of fruits and vegetables compared to their baseline consumption levels.[23]

Current issues

[edit]Childhood obesity is a public health concern. In a recent study done by medical researchers, from 2011-2012, 8.4% of young children ages 2–5, 17.7% of kids ages 6–11, and 20.5% of teens ages 12–19 are categorized as obese in the U.S.[24] Besides nutrition education, environmental factors such as a decrease in physical activity and increase in energy intake have led to more sedentary children.[25] This increase in body mass index has led to hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes among other chronic diseases.[25] Poor nutrition habits and lack of physical activity have led to this increase of obesity that leads from childhood to adulthood.[25] A lack of funding and insufficient resources have led to poor nutrition education.[26] Lack of funding has led to schools developing contracts with private companies such as soda and candy companies that allow vending machines and other products as well and has created a monopoly in public schools.[27]

Nutrition based policies use a trickle-down methods: federal, regional, state, local and school district policies.[26] Teachers have a more direct influence in nutrition education.[26] There are not a lot of studies that show how nutrition education policies affect the teachers in the schools they are meant to influence.[26]

Additional publications

[edit]- The Journal for Nutrition Education and Behavior, the official journal of the Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior, documents and disseminates original research, emerging issues and practices relevant to nutrition education and behavior worldwide.[28]

- The Journal of School Health, the journal that provides information regarding the roles of schools, school personnel, and the environment in regards to the health development of young children.[29]

- Nutrition Reviews is a journal that publishes new literature reviews on current topics such as clinical nutrition and nutrition policy.[7]

See also

[edit]- 5 A Day

- Food guide pyramid

- Fruits & Veggies – More Matters

- Healthy diet

- Healthy eating pyramid

- History of USDA nutrition guides

- Human nutrition

References

[edit]- ^ Nutrition Education | DSHS. https://www.dshs.wa.gov/altsa/program-services/nutrition-education . Accessed 29 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d Contento, I. R. (2008). "Nutrition education: Linking research, theory, and practice" (PDF). Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 17 (Suppl 1): 176–9. PMID 18296331.

- ^ a b c Pérez-Rodrigo, Carmen; Aranceta, Javier (2001). "School-based nutrition education: Lessons learned and new perspectives". Public Health Nutrition. 4 (1A): 131–139. doi:10.1079/PHN2000108. PMID 11255503. S2CID 24342976.

- ^ Ronda, G. (2001). "Stages of change, psychological factors and awareness of physical activity levels in the Netherlands". Health Promotion International. 16 (4): 305–314. doi:10.1093/heapro/16.4.305. PMID 11733449.

- ^ a b c Shannon, Barbara; Mullis, Rebecca; Bernardo, Valerie; Ervin, Bethene; Poehler, David L. (1992). "The Status of School-Based Nutrition Education at the State Agency Level". Journal of School Health. 62 (3): 88–92. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.1992.tb06024.x. PMID 1619903.

- ^ Womach, Jasper. "Agriculture: A Glossary of Terms, Programs, and Laws, 2005 Edition." CRS Report for Congress, 16 June 2005, https://happyhoursbbsr.com/how-to-inculcate-healthy-eating-habits-in-children/

- ^ a b About Nutrition Reviews, Oxford Academic. Accessed 29 November 2018.

- ^ a b Food and Nutrition, USDA. Accessed 29 November 2018.

- ^ a b c About FNS Food and Nutrition Service. Accessed 29 November 2018.

- ^ About CNPP | Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. https://www.cnpp.usda.gov/about-cnpp . Accessed 29 November 2018.

- ^ a b Office of Policy Support; Food and Nutrition Service; U.S. Department of Agriculture (May 2023). USDA Nutrition Education Coordination Report to Congress: Fiscal Year 2022 (PDF). pp. 3–9.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b NIFA Program Leadership (2021). The Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program Policies (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. pp. 3–5.

- ^ Education & The Workforce Committee (2016). Bill Summary: The Improving Child Nutrition and Education Act (PDF).

- ^ a b National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program: Nutrition Standards for All Foods Sold in School as Required by the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. Federal Register, 28 June 2013

- ^ "Public Health Service Act, 1944." Public Health Reports, vol. 109, no. 4, 1994, p. 468.

- ^ Nutrition in Schools, Health Law & Policy Institute. http://www.law.uh.edu/Healthlaw/perspectives/Children/020830Nutrition.html . Accessed 27 November 2018.

- ^ Frist, William. S. 1325–109th Congress (2005-2006): Improved Nutrition and Physical Activity Act. 28 June 2005, https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/senate-bill/1325 .

- ^ Cappellano, Kathleen L. (May 2011). "Let's Move-Tools to Fuel a Healthier Population". Nutrition Today. 46 (3): 149–154. doi:10.1097/NT.0b013e3181ec6a6d. ISSN 0029-666X.

- ^ Nutrition, Center for Food Safety and Applied (2022-02-25). "Using the Nutrition Facts Label and MyPlate to Make Healthier Choices". FDA.

- ^ "MyPlate | U.S. Department of Agriculture". www.myplate.gov. Retrieved 2022-12-05.

- ^ a b c Blitstein, Jonathan L.; Cates, Sheryl C.; Hersey, James; Montgomery, Doris; Shelley, Mack; Hradek, Christine; Kosa, Katherine; Bell, Loren; Long, Valerie; Williams, Pamela A.; Olson, Sara; Singh, Anita (2016). "Adding a Social Marketing Campaign to a School-Based Nutrition Education Program Improves Children's Dietary Intake: A Quasi-Experimental Study". Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 116 (8): 1285–1294. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2015.12.016. PMID 26857870.

- ^ Graig M. Hales, et al. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief, 288, Center for Disease Control, 1 November 2017, pp. 1–7, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db288.pdf .

- ^ a b c Ha, Eun-Jeong; Caine-Bish, Natalie (2009). "Effect of Nutrition Intervention Using a General Nutrition Course for Promoting Fruit and Vegetable Consumption among College Students". Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 41 (2): 103–109. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2008.07.001. PMID 19304255.

- ^ Hemphill, Thomas A. (December 2018). "Obesity in America: A Market Failure?". Business and Society Review. 123 (4): 619–630. doi:10.1111/basr.12157. hdl:2027.42/146865. S2CID 158126145.

- ^ a b c Ruebel, Meghan L., et al. Outcomes of a Family-Based Pediatric Obesity Program - Preliminary Results. p. 12.

- ^ a b c d McCaughtry, N.; Martin, J. J.; Fahlman, M.; Shen, B. (2012). "Urban health educators' perspectives and practices regarding school nutrition education policies". Health Education Research. 27 (1): 69–80. doi:10.1093/her/cyr101. PMID 22072137.

- ^ Ebbeling, Cara B.; Pawlak, Dorota B.; Ludwig, David S. (2002). "Childhood obesity: Public-health crisis, common sense cure". The Lancet. 360 (9331): 473–482. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09678-2. PMID 12241736. S2CID 6374501.

- ^ "Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior". Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior.

- ^ "Journal of School Health". Journal of School Health.