Dolores (2017 film)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

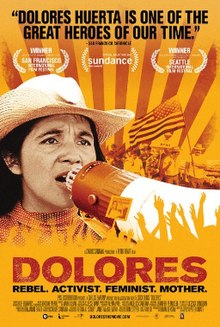

Dolores is a 2017 American documentary directed by Peter Bratt, on the life of Chicana labor union activist Dolores Huerta. It was produced by Brian Benson for PBS, with Benjamin Bratt and Alpita Patel serving as consulting producers and Carlos Santana as executive producer.[1]

Dolores centers on Dolores Huerta's committed work to organize California farmworkers as the co-founder of the UFW (United Farm Workers), in alliance with the Chicano Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, gay liberation and US-based LGBTQ social movements, and the late 20th century women's rights movement. Including recent and historical interviews with Huerta and her family members, the documentary includes historic film footage from the farmworker strikes and marches in Delano, California and New York City, the activism of the Delano grape strike that spread throughout the country, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy's meetings with the organizers during his presidential campaign, as well as interviews with UFW co-founder Cesar Chavez, theatre artist Luis Valdez, Angela Davis, Gloria Steinem, Hillary Clinton, and Barack Obama.

Plot

[edit]This article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (May 2018) |

The documentary begins discussing Dolores' life prior to her becoming the activist she is known for being today. Dolores during the 1940s and 50's was living out the typical life of a Chicano for that period. Even at an early age she was disturbed by the world around her, and felt unsatisfied with the life that she was living. She witnessed police brutality and other horrors that made her feel that there was not true justice or equality in the world she was living in. In addition, she was unsatisfied with her life as a young mother. Having been married and divorced twice she was looking for something to fulfill her and this is when she met Fred Ross.[2]

Fred Ross was community organizer in California who was searching for individuals who were willing to make the community better. His goals were immediately attractive to young Huerta because of Ross' focus on police brutality, and his efforts to combat it. Their relationship blossomed and by 1959 Dolores was head of the Stockton Chapter of the Community Service Organization, a group dedicated to helping Latino individuals in the community.

During this time period Dolores proved to be a great leader, organizer and lobbyist. She would pack hundreds of people into the office of legislators until they came around to supporting legislation she wanted. In addition, it was during these early years that she was introduced, by Ross, to Cesar Chavez. Chavez had the goal of organizing a union for farm workers and knew Dolores was going to be the person he needed to help him achieve this goal. Between the efforts of both Huerta and Chavez the United Farm Workers of America was born. The documentary discusses the extensive commitment Dolores made when starting up this organization. She was forced to pick up and move her family to Delano, California in order to be connected to the agricultural communities she was trying to help. She was forced to even leave some of her younger children behind for fear they would not be able to endure the circumstances of their new living conditions and mothers dedication to the UFW. She sacrificed a lot during the early years even some of the things she enjoyed the most, like listening to jazz music.

1965

[edit]While UFW had made great strides in the relations of farm workers and farm owners the Filipino workers going on strike. It was then that Huerta and Chavez realized that they needed more inclusion in their organization. Not just Latino's were facing these horrible working conditions. As the UFW started to include more groups of workers they also started to recruit more and more individuals to work for them. In fact, there were more women involved in the UFW than in any other union in the United States combined. The following year, 1966, the UFW saw its first major success following the March to Sacramento. The march from Delano to Sacramento California was the largest gathering of farmworkers in California history. As a result of the march, the Schenley Contract was negotiated. This contract was the first between farm workers and growers.[2]

1968

[edit]During Robert F. Kennedy's run for president he became a huge supporter of the UFW and disenfranchised groups as a whole. As a senator he stood with the movement in regards to their treatment during the strikes. He actively went after the corporations who were mistreating the farmworkers. Due to his support of the UFW, the UFW fully supported his presidential run. Everyone went and worked on his campaign. UFW members would knock on doors persuading people to vote and even registering them to vote.[2]

The relationship between Senator Kennedy and Dolores was so strong that she was actually with him the night of his assassination. This event was very jarring for Dolores and the rest of the UFW because they felt that the one person who would actually stand up for them was gone. In addition, his assassination made Dolores even more passionate about non-violence in her movement.

1973

[edit]By 1973 the UFW had successfully organized three year contracts in California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. As the contracts were about to expire the UFW started to experience problems with the teamsters. They wanted to represent all of the people formerly represented by the UFW. They were ultimately successful in a lot of their efforts. As a result, the UFW went on strikes and boycotts that often turned extremely violent so even resulting in death. This was all particularly upsetting for Dolores because it became clear to her that the current system did not want "brown people" to have an organization or have power.[2]

1988

[edit]In 1988, George Bush was holding a fundraiser in California. Many members of the UFW, including Dolores went and were peacefully protesting outside the building. As the crowd grew larger, crowd control officers began pushing and yelling at the protestors to move back. Dolores was following their orders when suddenly one of the officers started to hit and bash her with a police baton. She was hospitalized with three broken ribs as well as had to undergo emergency spleen removal. The beating resulted in a very long hospitalization and Dolores was weak for many many months. She had to take a long absence from the movement she had worked so passionately for many years.[2]

1993

[edit]In 1993, Chavez was found dead of natural causes in Arizona. His death was extremely upsetting to Dolores as well as the rest of the UFW. While many members and the public wanted to see Dolores as the new president, considering how equally she and Chavez had worked for decades, however the board voted to appoint someone else. Following this decision it was clear that others did not value the opinion of Dolores as Chavez had at that her voice in the UFW was slowly shrinking.[2]

2002

[edit]In 2002, less than 10 years after Chavez's death, Dolores handed in her resignation to the UFW. That same year she received a Puffin Grant of $100,000 which allowed her to start her own foundation the Dolores Huerta Foundation. This foundation has allowed Dolores to continue to give back and touch on every single issue that she is passionate about. She was able to connect everything that she had every fought for or disagreed with under one umbrella.[2]

Intersectionality of race, class, and gender in Dolores

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (July 2018) |

Not only in the documentary, but in articles published in response to the film it is evident that Dolores Huerta experienced overt sexism throughout her activist career. While she led the fight for the acceptance, and equality for those who were less fortunate than herself she in turn was scrutinized by the public and her fellow activist. She was criticized for having too many children, particular out of wedlock, as well as, never being at home to take care of them.[3] One of the interviews in particular during the documentary highlights not only the oppression she face, but also the oppression of all women during the 1960s. Huerta is asked what she would do if given $5,000, to which she immediately respond she would donate it to the movement.[3] The reporter returns with the response of "But don’t you ever have the average woman’s dream of going out to some spa and being relaxed and having a new hairdo and buying a great dress and having a big party?”[3] In addition, following the death of Cesar Chavez, Huerta was not even given the presidency of the organization she founded. This sort of oppression led Huerta to become a huge supporter of the feminist movement, becoming friends with other influencers such as Gloria Steinem.

Production and Reception

[edit]The production of Dolores occurred over a span of 4 years, and was the brainchild of musician Carlos Santana.[citation needed] Santana approached Peter Bratt about making the documentary in 2013. Bratt was quoted saying "When Carlos called about doing the film, I had to do it. I’ve always wanted to make a superhero movie and as Carlos says, she’s a real wonder woman. The challenge became finding a creative way to tell a compelling story - not just about an important historical figure, but how to engage a whole new generation that may not even know who she is."[4] Bratt did this by immersing himself in the history of Dolores Huerta and the farmworkers movement for more than four years.[4] Reception of the film was controversial before it was even released. Santana and Bratt struggled to find a network willing to partner with them. While it was ultimately picked up by PBS for Independent Lens, networks such as Netflix, HBO, and Telemundo refused.[5] The sentiments after the film was released are much different however. The documentary originally aired at the Sundance Film Festival[6] The producers felt that this film, and Huerta as a women, are an inspiration to female activist today involved with things such as the #MeTooMovement.[6] The film has also received praise from various critics as well as multiple awards. Specific reviews say that the film was "exuberantly inspiring,"a documentary of exceptional storytelling power," and "energetic, engaging".[7]

Awards

[edit]The film has received the following awards in 2017:

- Audience Award: Best Documentary Feature at the SF Film Festival

- Golden Space Needle Award: Best Documentary Feature at the Seattle International Film Festival

- Audience Award: Best Documentary Award at the Montclair Film Festival[8]

- Audience Award: Best Documentary at the Denver Women + Film Festival

- Audience Award: Best Feature Film at the Houston Latino Film Festival[9]

- Audience Choice Award: Best Feature Documentary at the Minneapolis/St. Paul International Film Festival

- Nashville Area Hispanic Chamber of Commerce Award at the Nashville Film Festival[10]

After airing on PBS in 2018, Dolores won a 2018 Peabody Award,[11] and was nominated for an Emmy for Outstanding Business and Economic Documentary at the 40th News and Documentary Emmy Award.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ "'Dolores' Comes to U.S. Theaters Beginning Sept. 1". Dolores The Movie. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Dolores | Portrait of Labor and Feminist Icon Dolores Huerta | Independent Lens | PBS". Independent Lens. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ^ a b c Merry, Stephanie (2017-09-13). "The new documentary 'Dolores' has a few lessons for the #resistance". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ^ a b Villafañe, Veronica. "Revealing Carlos Santana-Produced Film About Labor Rights Icon Dolores Huerta Opens In Theaters". Forbes. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- ^ "Carlos Santana Says Dolores Huerta Film Will Inspire 'Sisters of All Ages'". Billboard. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- ^ a b "Dolores Director Takes Us Behind the Scenes of His Acclaimed Film on Labor and Feminist Activist Dolores Huerta". PEOPLE.com. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- ^ "Press". Dolores The Movie. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- ^ Erbland, Kate. "'Dolores' Trailer: Feminist Pioneer Dolores Huerta Documentary". Indiewire.com. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ "PBS Doc About Civil Rights Activist Dolores Huerta Gets Theatrical Release Date". Blog.womenandhollywood.com. 29 June 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ "Dolores". IMDb.com. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ "The Best Stories of 2018". Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ "NOMINEES FOR THE 40th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED – The Emmys". Retrieved 2019-08-10.

External links

[edit]- Dolores at IMDb

- Dolores at Independent Lens