Small population size

Small populations can behave differently from larger populations. They are often the result of population bottlenecks from larger populations, leading to loss of heterozygosity and reduced genetic diversity and loss or fixation of alleles and shifts in allele frequencies.[1] A small population is then more susceptible to demographic and genetic stochastic events, which can impact the long-term survival of the population. Therefore, small populations are often considered at risk of endangerment or extinction, and are often of conservation concern.

Demographic effects

[edit]

The influence of stochastic variation in demographic (reproductive and mortality) rates is much higher for small populations than large ones. Stochastic variation in demographic rates causes small populations to fluctuate randomly in size. This variation could be a result of unequal sex ratios, high variance in family size, inbreeding, or fluctuating population size.[1] The smaller the population, the greater the probability that fluctuations will lead to extinction.

One demographic consequence of a small population size is the probability that all offspring in a generation are of the same sex, and where males and females are equally likely to be produced (see sex ratio), is easy to calculate: it is given by (the chance of all animals being females is ; the same holds for all males, thus this result). This can be a problem in very small populations. In 1977, the last 18 kākāpō on a Fiordland island in New Zealand were all male, though the probability of this would only be 0.0000076 if determined by chance (however, females are generally preyed upon more often than males and kakapo may be subject to sex allocation). With a population of just three individuals the probability of them all being the same sex is 0.25. Put another way, for every four species reduced to three individuals (or more precisely three individuals in the effective population), one will become extinct within one generation just because they are all the same sex. If the population remains at this size for several generations, such an event becomes almost inevitable.

Environmental effects

[edit]The environment can directly affect the survival of a small population. Some detrimental effects include stochastic variation in the environment (year to year variation in rainfall, temperature), which can produce temporally correlated birth and death rates (i.e. 'good' years when birth rates are high and death rates are low and 'bad' years when birth rates are low and death rates are high) that lead to fluctuations in the population size. Again, smaller populations are more likely to become extinct due to these environmentally generated population fluctuations than the large populations.

The environment can also introduce beneficial traits to a small population that promote its persistence. In the small, fragmented populations of the acorn woodpecker, minimal immigration is sufficient for population persistence. Despite the potential genetic consequences of having a small population size, the acorn woodpecker is able to avoid extinction and the classification as an endangered species because of this environmental intervention causing neighboring populations to immigrate.[2] Immigration promotes survival by increasing genetic diversity, which will be discussed in the next section as a harmful factor in small populations.

Genetic effects

[edit]

Conservationists are often worried about a loss of genetic variation in small populations. There are two types of genetic variation that are important when dealing with small populations:

- The degree of homozygosity within individuals in a population; i.e. the proportion of an individual's loci that contain homozygous rather than heterozygous alleles. Many deleterious alleles are only harmful in the homozygous form.[1]

- The degree of monomorphism/polymorphism within a population; i.e. how many different alleles of the same gene exist in the gene pool of a population. Genetic drift and the likelihood of inbreeding tend to have greater impacts on small populations, which can lead to speciation.[3] Both drift and inbreeding cause a reduction in genetic diversity, which is associated with a reduced population growth rate, reduced adaptive potential to environmental changes, and increased risk of extinction.[3] The effective population size (Ne), or the reproducing part of a population is often lower than the actual population size in small populations.[4] The Ne of a population is closest in size to the generation that had the smallest Ne. This is because alleles lost in generations of low populations are not regained when the population size increases. For example, the Northern Elephant Seal was reduced to 20-30 individuals, but now there are 100,000 due to conservation efforts. However the effective population size is only 60.

Contributing genetic factors

[edit]

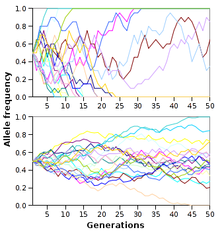

- Genetic drift: Genetic variation is determined by the joint action of natural selection and genetic drift (chance). In small populations, selection is less effective, and the relative importance of genetic drift is higher because deleterious alleles can become more frequent and 'fixed' in a population due to chance. The allele selected for by natural selection becomes fixed more quickly, resulting in the loss of the other allele at that locus (in the case of a two allele locus) and an overall loss of genetic diversity.[5][6][7] Alternatively, larger populations are affected less by genetic drift because drift is measured using the equation 1/2N, with "N" referring to population size; it takes longer for alleles to become fixed because "N" is higher. One example of large populations showing greater adaptive evolutionary ability is the red flour beetle. Selection acting on the body color of the red flour beetle was found to be more consistent in large than in small populations; although the black allele was selected against, one of the small populations observed became homozygous for the deleterious black allele (this did not occur in the large populations).[8] for Any allele—deleterious, beneficial, or neutral—is more likely to be lost from a small population (gene pool) than a large one. This results in a reduction in the number of forms of alleles in a small population, especially in extreme cases such as monomorphism, where there is only one form of the allele. Continued fixation of deleterious alleles in small populations is called Muller's ratchet, and can lead to mutational meltdown.

- Inbreeding: In a small population, closely related individuals are more likely to breed together. The offspring of related parents have a higher number of homozygous loci than the offspring of unrelated parents.[1] Inbreeding causes a decrease in the reproductive fitness of a population because of a decrease in its heterozygosity from the repeated mating of closely related individuals or selfing.[1] Inbreeding may also lead to inbreeding depression when heterozygosity is minimized to the point where deleterious mutations that reduce fitness become more prevalent.[9] Inbreeding depression is a trend in many plants and animals with small populations sizes and increases their risk of extinction.[10][11][12] Inbreeding depression is usually taken to mean any immediate harmful effect, on individuals or on the population, of a decrease in either type of genetic variation. Inbreeding depression can almost never be found in declining populations that were not very large to begin with; it is somewhat common in large populations becoming small though. This is the cause of purging selection which is most efficient in populations that are very but not dangerously inbred.

- Genetic adaptation to fragmented habitat: Over time species evolve to become adapted to their environment. This can lead to limited fitness in the face of stochastic changes. For example, birds on islands, such as the Galapagos Flightless Cormorant or the Kiwi of New Zealand, have been known to develop flightlessness. This trait results in a limited ability to avoid predators and disease which could perpetuate further problems in the face of climate change.[13][14] Fragmented populations also see genetic adaptation. For example, habitat fragmentation has resulted in a shift toward increased selfing in plant populations.[15]

Examples of genetic consequences that have happened in inbred populations are high levels of hatching failure,[16][17] bone abnormalities, low infant survivability, and decrease in birth rates. Some populations that have these consequences are cheetahs, who suffer with low infant survivability and a decrease in birth rate due to having gone through a population bottleneck. Northern elephant seals, who also went through a population bottleneck, have had cranial bone structure changes to the lower mandibular tooth row. The wolves on Isle Royale, a population restricted to the island in Lake Superior, have bone malformations in the vertebral column in the lumbosacral region. These wolves also have syndactyly, which is the fusion of soft tissue between the toes of the front feet. These types of malformations are caused by inbreeding depression or genetic load.[18]

Island populations

[edit]

Island populations often also have small populations due to geographic isolation, limited habitat and high levels of endemism. Because their environments are so isolated gene flow is poor within island populations. Without the introduction of genetic diversity from gene flow, alleles are quickly fixed or lost. This reduces island populations' ability to adapt to any new circumstances[19] and can result in higher levels of extinction. The majority of mammal, bird, and reptile extinctions since the 1600s have been from island populations. Moreover, 20% of bird species live on islands, but 90% of all bird extinctions have been from island populations.[13] Human activities have been the major cause of extinctions on island in the past 50,000 years due to the introduction of exotic species, habitat loss and over-exploitation.[20]

The Galapagos penguin is an endangered endemic species of the Galapagos islands. Its population has seen extreme fluctuations in population size due to marine perturbations, which have become more extreme due to climate change. The population has ranged from as high as 10,000 specimens to as low as 700. Currently it is estimated there are about 1000 mature individuals.[1]

Conservation

[edit]Conservation efforts for small populations at risk of extinction focus on increasing population size as well as genetic diversity, which determines the fitness of a population and its long-term persistence.[21] Some methods include captive breeding and genetic rescue. Stabilizing the variance in family size is an effective way can double the effective population size and is often used in conservation strategies.[1]

See also

[edit]- Decline in amphibian populations

- Founder effect

- Functional extinction

- Gene pool

- Genetic erosion

- Genetic pollution

- Minimum viable population

- Muller's ratchet

- Mutational meltdown

- Pollinator decline

- Population genetics

- Population decline

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Frankham, R., Briscoe, D. A., & Ballou, J. D. (2002). Introduction to conservation genetics. Cambridge university press.

- ^ Stacey, Peter B.; Taper, Mark (1992-02-01). "Environmental Variation and the Persistence of Small Populations". Ecological Applications. 2 (1): 18–29. doi:10.2307/1941886. ISSN 1939-5582. JSTOR 1941886. PMID 27759195. S2CID 37038826.

- ^ a b Purdue University. "Captive breeding: Effect of small population size". www.purdue.edu/captivebreeding/effect-of-small-population-size/. Accessed 1 June 2017.

- ^ Lande, Russell, and George F. Barrowclough. "Effective population size, genetic variation, and their use in population management." Viable populations for conservation 87 (1987): 124.

- ^ Nei, Masatoshi. "Estimation of average heterozygosity and genetic distance from a small number of individuals." Genetics 89.3 (1978): 583-590.

- ^ Lande, Russell. "Natural selection and random genetic drift in phenotypic evolution." Evolution (1976): 314-334.

- ^ Lacy, Robert C. "Loss of genetic diversity from managed populations: interacting effects of drift, mutation, immigration, selection, and population subdivision." Conservation Biology 1.2 (1987): 143-158.

- ^ TFC, Falconer, DS Mackay. "Introduction to quantitative genetics." 4th Longman Essex, UK (1996).

- ^ Charlesworth, D., and B. Charlesworth. "Inbreeding depression and its evolutionary consequences". Annual review of ecology and systematics 18.1 (1987): 237–268.

- ^ Newman, Dara, and Diana Pilson. "Increased probability of extinction due to decreased genetic effective population size: experimental populations of Clarkia pulchella." Evolution (1997): 354-362.

- ^ Saccheri, Ilik, et al. "Inbreeding and extinction in a butterfly metapopulation." Nature 392.6675 (1998): 491.

- ^ Byers, D. L., and D. M. Waller. "Do plant populations purge their genetic load? Effects of population size and mating history on inbreeding depression." Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 30.1 (1999): 479-513.

- ^ a b Frankham, R. (1997). Do island populations have less genetic variation than mainland populations?. Heredity, 78(3).

- ^ Ramstad, K. M., Colbourne, R. M., Robertson, H. A., Allendorf, F. W., & Daugherty, C. H. (2013). Genetic consequences of a century of protection: serial founder events and survival of the little spotted kiwi (Apteryx owenii). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 280(1762), 20130576.

- ^ Aguilar, R., Quesada, M., Ashworth, L., Herrerias‐Diego, Y., & Lobo, J. (2008). "Genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation in plant populations: susceptible signals in plant traits and methodological approaches". Molecular Ecology, 17(24), 5177–5188. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03971.x. PMID 19120995

- ^ Briskie, James (2004). "Hatching failure increases with severity of population bottlenecks in birds". PNAS. 110 (2): 558–561. doi:10.1073/pnas.0305103101. PMC 327186. PMID 14699045.

- ^ Brekke, Patricia (2010). "Sensitive males: inbreeding depression in an endangered bird". Proc. R. Soc. B. 277 (1700): 3677–3684. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1144. PMC 2982255. PMID 20591862.

- ^ Raikkonen, J. et al. 2009. Congenital Bone Deformities and the Inbred Wolves (Canis lupus) of Isle Royale. Biological Conservation. 142: 1025–1031.

- ^ de Villemereuil, Pierre (2019). "Little Adaptive Potential in a Threatened Passerine Bird". Current Biology. 29 (5): 889–894. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.01.072. PMID 30799244.

- ^ World Resources Institute, International Union for Conservation of Nature, & Natural Resources. (1992). Global biodiversity strategy: Guidelines for action to save, study, and use earth's biotic wealth sustainably and equitably. World Resources Inst.

- ^ Smith, S., & Hughes, J. (2008). Microsatellite and mitochondrial DNA variation defines island genetic reservoirs for reintroductions of an endangered Australian marsupial, Perameles bougainville. Conservation Genetics, 9(3), 547.