Alloy

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2024) |

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which in most cases at least one is a metallic element, although it is also sometimes used for mixtures of elements; herein only metallic alloys are described. Most alloys are metallic and show good electrical conductivity, ductility, opacity, and luster, and may have properties that differ from those of the pure elements such as increased strength or hardness. In some cases, an alloy may reduce the overall cost of the material while preserving important properties. In other cases, the mixture imparts synergistic properties such as corrosion resistance or mechanical strength.

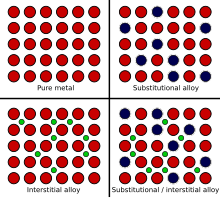

In an alloy, the atoms are joined by metallic bonding rather than by covalent bonds typically found in chemical compounds.[1] The alloy constituents are usually measured by mass percentage for practical applications, and in atomic fraction for basic science studies. Alloys are usually classified as substitutional or interstitial alloys, depending on the atomic arrangement that forms the alloy. They can be further classified as homogeneous (consisting of a single phase), or heterogeneous (consisting of two or more phases) or intermetallic. An alloy may be a solid solution of metal elements (a single phase, where all metallic grains (crystals) are of the same composition) or a mixture of metallic phases (two or more solutions, forming a microstructure of different crystals within the metal).

Examples of alloys include red gold (gold and copper), white gold (gold and silver), sterling silver (silver and copper), steel or silicon steel (iron with non-metallic carbon or silicon respectively), solder, brass, pewter, duralumin, bronze, and amalgams.

Alloys are used in a wide variety of applications, from the steel alloys, used in everything from buildings to automobiles to surgical tools, to exotic titanium alloys used in the aerospace industry, to beryllium-copper alloys for non-sparking tools.

Characteristics

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements, which forms an impure substance (admixture) that retains the characteristics of a metal. An alloy is distinct from an impure metal in that, with an alloy, the added elements are well controlled to produce desirable properties, while impure metals such as wrought iron are less controlled, but are often considered useful. Alloys are made by mixing two or more elements, at least one of which is a metal. This is usually called the primary metal or the base metal, and the name of this metal may also be the name of the alloy. The other constituents may or may not be metals but, when mixed with the molten base, they will be soluble and dissolve into the mixture. The mechanical properties of alloys will often be quite different from those of its individual constituents. A metal that is normally very soft (malleable), such as aluminium, can be altered by alloying it with another soft metal, such as copper. Although both metals are very soft and ductile, the resulting aluminium alloy will have much greater strength. Adding a small amount of non-metallic carbon to iron trades its great ductility for the greater strength of an alloy called steel. Due to its very-high strength, but still substantial toughness, and its ability to be greatly altered by heat treatment, steel is one of the most useful and common alloys in modern use. By adding chromium to steel, its resistance to corrosion can be enhanced, creating stainless steel, while adding silicon will alter its electrical characteristics, producing silicon steel.

Like oil and water, a molten metal may not always mix with another element. For example, pure iron is almost completely insoluble with copper. Even when the constituents are soluble, each will usually have a saturation point, beyond which no more of the constituent can be added. Iron, for example, can hold a maximum of 6.67% carbon. Although the elements of an alloy usually must be soluble in the liquid state, they may not always be soluble in the solid state. If the metals remain soluble when solid, the alloy forms a solid solution, becoming a homogeneous structure consisting of identical crystals, called a phase. If as the mixture cools the constituents become insoluble, they may separate to form two or more different types of crystals, creating a heterogeneous microstructure of different phases, some with more of one constituent than the other. However, in other alloys, the insoluble elements may not separate until after crystallization occurs. If cooled very quickly, they first crystallize as a homogeneous phase, but they are supersaturated with the secondary constituents. As time passes, the atoms of these supersaturated alloys can separate from the crystal lattice, becoming more stable, and forming a second phase that serves to reinforce the crystals internally.

Some alloys, such as electrum—an alloy of silver and gold—occur naturally. Meteorites are sometimes made of naturally occurring alloys of iron and nickel, but are not native to the Earth. One of the first alloys made by humans was bronze, which is a mixture of the metals tin and copper. Bronze was an extremely useful alloy to the ancients, because it is much stronger and harder than either of its components. Steel was another common alloy. However, in ancient times, it could only be created as an accidental byproduct from the heating of iron ore in fires (smelting) during the manufacture of iron. Other ancient alloys include pewter, brass and pig iron. In the modern age, steel can be created in many forms. Carbon steel can be made by varying only the carbon content, producing soft alloys like mild steel or hard alloys like spring steel. Alloy steels can be made by adding other elements, such as chromium, molybdenum, vanadium or nickel, resulting in alloys such as high-speed steel or tool steel. Small amounts of manganese are usually alloyed with most modern steels because of its ability to remove unwanted impurities, like phosphorus, sulfur and oxygen, which can have detrimental effects on the alloy. However, most alloys were not created until the 1900s, such as various aluminium, titanium, nickel, and magnesium alloys. Some modern superalloys, such as incoloy, inconel, and hastelloy, may consist of a multitude of different elements.

An alloy is technically an impure metal, but when referring to alloys, the term impurities usually denotes undesirable elements. Such impurities are introduced from the base metals and alloying elements, but are removed during processing. For instance, sulfur is a common impurity in steel. Sulfur combines readily with iron to form iron sulfide, which is very brittle, creating weak spots in the steel.[2] Lithium, sodium and calcium are common impurities in aluminium alloys, which can have adverse effects on the structural integrity of castings. Conversely, otherwise pure-metals that contain unwanted impurities are often called "impure metals" and are not usually referred to as alloys. Oxygen, present in the air, readily combines with most metals to form metal oxides; especially at higher temperatures encountered during alloying. Great care is often taken during the alloying process to remove excess impurities, using fluxes, chemical additives, or other methods of extractive metallurgy.[3]

Theory

Alloying a metal is done by combining it with one or more other elements. The most common and oldest alloying process is performed by heating the base metal beyond its melting point and then dissolving the solutes into the molten liquid, which may be possible even if the melting point of the solute is far greater than that of the base. For example, in its liquid state, titanium is a very strong solvent capable of dissolving most metals and elements. In addition, it readily absorbs gases like oxygen and burns in the presence of nitrogen. This increases the chance of contamination from any contacting surface, and so must be melted in vacuum induction-heating and special, water-cooled, copper crucibles.[4] However, some metals and solutes, such as iron and carbon, have very high melting-points and were impossible for ancient people to melt. Thus, alloying (in particular, interstitial alloying) may also be performed with one or more constituents in a gaseous state, such as found in a blast furnace to make pig iron (liquid-gas), nitriding, carbonitriding or other forms of case hardening (solid-gas), or the cementation process used to make blister steel (solid-gas). It may also be done with one, more, or all of the constituents in the solid state, such as found in ancient methods of pattern welding (solid-solid), shear steel (solid-solid), or crucible steel production (solid-liquid), mixing the elements via solid-state diffusion.

By adding another element to a metal, differences in the size of the atoms create internal stresses in the lattice of the metallic crystals; stresses that often enhance its properties. For example, the combination of carbon with iron produces steel, which is stronger than iron, its primary element. The electrical and thermal conductivity of alloys is usually lower than that of the pure metals. The physical properties, such as density, reactivity, Young's modulus of an alloy may not differ greatly from those of its base element, but engineering properties such as tensile strength,[5] ductility, and shear strength may be substantially different from those of the constituent materials. This is sometimes a result of the sizes of the atoms in the alloy, because larger atoms exert a compressive force on neighboring atoms, and smaller atoms exert a tensile force on their neighbors, helping the alloy resist deformation. Sometimes alloys may exhibit marked differences in behavior even when small amounts of one element are present. For example, impurities in semiconducting ferromagnetic alloys lead to different properties, as first predicted by White, Hogan, Suhl, Tian Abrie and Nakamura.[6][7]

Unlike pure metals, most alloys do not have a single melting point, but a melting range during which the material is a mixture of solid and liquid phases (a slush). The temperature at which melting begins is called the solidus, and the temperature when melting is just complete is called the liquidus. For many alloys there is a particular alloy proportion (in some cases more than one), called either a eutectic mixture or a peritectic composition, which gives the alloy a unique and low melting point, and no liquid/solid slush transition.

Heat treatment

Alloying elements are added to a base metal, to induce hardness, toughness, ductility, or other desired properties. Most metals and alloys can be work hardened by creating defects in their crystal structure. These defects are created during plastic deformation by hammering, bending, extruding, et cetera, and are permanent unless the metal is recrystallized. Otherwise, some alloys can also have their properties altered by heat treatment. Nearly all metals can be softened by annealing, which recrystallizes the alloy and repairs the defects, but not as many can be hardened by controlled heating and cooling. Many alloys of aluminium, copper, magnesium, titanium, and nickel can be strengthened to some degree by some method of heat treatment, but few respond to this to the same degree as does steel.[8]

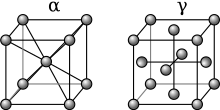

The base metal iron of the iron-carbon alloy known as steel, undergoes a change in the arrangement (allotropy) of the atoms of its crystal matrix at a certain temperature (usually between 820 °C (1,500 °F) and 870 °C (1,600 °F), depending on carbon content). This allows the smaller carbon atoms to enter the interstices of the iron crystal. When this diffusion happens, the carbon atoms are said to be in solution in the iron, forming a particular single, homogeneous, crystalline phase called austenite. If the steel is cooled slowly, the carbon can diffuse out of the iron and it will gradually revert to its low temperature allotrope. During slow cooling, the carbon atoms will no longer be as soluble with the iron, and will be forced to precipitate out of solution, nucleating into a more concentrated form of iron carbide (Fe3C) in the spaces between the pure iron crystals. The steel then becomes heterogeneous, as it is formed of two phases, the iron-carbon phase called cementite (or carbide), and pure iron ferrite. Such a heat treatment produces a steel that is rather soft. If the steel is cooled quickly, however, the carbon atoms will not have time to diffuse and precipitate out as carbide, but will be trapped within the iron crystals. When rapidly cooled, a diffusionless (martensite) transformation occurs, in which the carbon atoms become trapped in solution. This causes the iron crystals to deform as the crystal structure tries to change to its low temperature state, leaving those crystals very hard but much less ductile (more brittle).

While the high strength of steel results when diffusion and precipitation is prevented (forming martensite), most heat-treatable alloys are precipitation hardening alloys, that depend on the diffusion of alloying elements to achieve their strength. When heated to form a solution and then cooled quickly, these alloys become much softer than normal, during the diffusionless transformation, but then harden as they age. The solutes in these alloys will precipitate over time, forming intermetallic phases, which are difficult to discern from the base metal. Unlike steel, in which the solid solution separates into different crystal phases (carbide and ferrite), precipitation hardening alloys form different phases within the same crystal. These intermetallic alloys appear homogeneous in crystal structure, but tend to behave heterogeneously, becoming hard and somewhat brittle.[8]

In 1906, precipitation hardening alloys were discovered by Alfred Wilm. Precipitation hardening alloys, such as certain alloys of aluminium, titanium, and copper, are heat-treatable alloys that soften when quenched (cooled quickly), and then harden over time. Wilm had been searching for a way to harden aluminium alloys for use in machine-gun cartridge cases. Knowing that aluminium-copper alloys were heat-treatable to some degree, Wilm tried quenching a ternary alloy of aluminium, copper, and the addition of magnesium, but was initially disappointed with the results. However, when Wilm retested it the next day he discovered that the alloy increased in hardness when left to age at room temperature, and far exceeded his expectations. Although an explanation for the phenomenon was not provided until 1919, duralumin was one of the first "age hardening" alloys used, becoming the primary building material for the first Zeppelins, and was soon followed by many others.[9] Because they often exhibit a combination of high strength and low weight, these alloys became widely used in many forms of industry, including the construction of modern aircraft.[10]

Mechanisms

When a molten metal is mixed with another substance, there are two mechanisms that can cause an alloy to form, called atom exchange and the interstitial mechanism. The relative size of each element in the mix plays a primary role in determining which mechanism will occur. When the atoms are relatively similar in size, the atom exchange method usually happens, where some of the atoms composing the metallic crystals are substituted with atoms of the other constituent. This is called a substitutional alloy. Examples of substitutional alloys include bronze and brass, in which some of the copper atoms are substituted with either tin or zinc atoms respectively.

In the case of the interstitial mechanism, one atom is usually much smaller than the other and can not successfully substitute for the other type of atom in the crystals of the base metal. Instead, the smaller atoms become trapped in the interstitial sites between the atoms of the crystal matrix. This is referred to as an interstitial alloy. Steel is an example of an interstitial alloy, because the very small carbon atoms fit into interstices of the iron matrix.

Stainless steel is an example of a combination of interstitial and substitutional alloys, because the carbon atoms fit into the interstices, but some of the iron atoms are substituted by nickel and chromium atoms.[8]

History and examples

Meteoric iron

The use of alloys by humans started with the use of meteoric iron, a naturally occurring alloy of nickel and iron. It is the main constituent of iron meteorites. As no metallurgic processes were used to separate iron from nickel, the alloy was used as it was.[11] Meteoric iron could be forged from a red heat to make objects such as tools, weapons, and nails. In many cultures it was shaped by cold hammering into knives and arrowheads. They were often used as anvils. Meteoric iron was very rare and valuable, and difficult for ancient people to work.[12]

Bronze and brass

Iron is usually found as iron ore on Earth, except for one deposit of native iron in Greenland, which was used by the Inuit.[13] Native copper, however, was found worldwide, along with silver, gold, and platinum, which were also used to make tools, jewelry, and other objects since Neolithic times. Copper was the hardest of these metals, and the most widely distributed. It became one of the most important metals to the ancients. Around 10,000 years ago in the highlands of Anatolia (Turkey), humans learned to smelt metals such as copper and tin from ore. Around 2500 BC, people began alloying the two metals to form bronze, which was much harder than its ingredients. Tin was rare, however, being found mostly in Great Britain. In the Middle East, people began alloying copper with zinc to form brass.[14] Ancient civilizations took into account the mixture and the various properties it produced, such as hardness, toughness and melting point, under various conditions of temperature and work hardening, developing much of the information contained in modern alloy phase diagrams.[15] For example, arrowheads from the Chinese Qin dynasty (around 200 BC) were often constructed with a hard bronze-head, but a softer bronze-tang, combining the alloys to prevent both dulling and breaking during use.[16]

Amalgams

Mercury has been smelted from cinnabar for thousands of years. Mercury dissolves many metals, such as gold, silver, and tin, to form amalgams (an alloy in a soft paste or liquid form at ambient temperature). Amalgams have been used since 200 BC in China for gilding objects such as armor and mirrors with precious metals. The ancient Romans often used mercury-tin amalgams for gilding their armor. The amalgam was applied as a paste and then heated until the mercury vaporized, leaving the gold, silver, or tin behind.[17] Mercury was often used in mining, to extract precious metals like gold and silver from their ores.[18]

Precious metals

Many ancient civilizations alloyed metals for purely aesthetic purposes. In ancient Egypt and Mycenae, gold was often alloyed with copper to produce red-gold, or iron to produce a bright burgundy-gold. Gold was often found alloyed with silver or other metals to produce various types of colored gold. These metals were also used to strengthen each other, for more practical purposes. Copper was often added to silver to make sterling silver, increasing its strength for use in dishes, silverware, and other practical items. Quite often, precious metals were alloyed with less valuable substances as a means to deceive buyers.[19] Around 250 BC, Archimedes was commissioned by the King of Syracuse to find a way to check the purity of the gold in a crown, leading to the famous bath-house shouting of "Eureka!" upon the discovery of Archimedes' principle.[20]

Pewter

The term pewter covers a variety of alloys consisting primarily of tin. As a pure metal, tin is much too soft to use for most practical purposes. However, during the Bronze Age, tin was a rare metal in many parts of Europe and the Mediterranean, so it was often valued higher than gold. To make jewellery, cutlery, or other objects from tin, workers usually alloyed it with other metals to increase strength and hardness. These metals were typically lead, antimony, bismuth or copper. These solutes were sometimes added individually in varying amounts, or added together, making a wide variety of objects, ranging from practical items such as dishes, surgical tools, candlesticks or funnels, to decorative items like ear rings and hair clips.

The earliest examples of pewter come from ancient Egypt, around 1450 BC. The use of pewter was widespread across Europe, from France to Norway and Britain (where most of the ancient tin was mined) to the Near East.[21] The alloy was also used in China and the Far East, arriving in Japan around 800 AD, where it was used for making objects like ceremonial vessels, tea canisters, or chalices used in shinto shrines.[22]

Iron

The first known smelting of iron began in Anatolia, around 1800 BC. Called the bloomery process, it produced very soft but ductile wrought iron. By 800 BC, iron-making technology had spread to Europe, arriving in Japan around 700 AD. Pig iron, a very hard but brittle alloy of iron and carbon, was being produced in China as early as 1200 BC, but did not arrive in Europe until the Middle Ages. Pig iron has a lower melting point than iron, and was used for making cast-iron. However, these metals found little practical use until the introduction of crucible steel around 300 BC. These steels were of poor quality, and the introduction of pattern welding, around the 1st century AD, sought to balance the extreme properties of the alloys by laminating them, to create a tougher metal. Around 700 AD, the Japanese began folding bloomery-steel and cast-iron in alternating layers to increase the strength of their swords, using clay fluxes to remove slag and impurities. This method of Japanese swordsmithing produced one of the purest steel-alloys of the ancient world.[15]

While the use of iron started to become more widespread around 1200 BC, mainly because of interruptions in the trade routes for tin, the metal was much softer than bronze. However, very small amounts of steel, (an alloy of iron and around 1% carbon), was always a byproduct of the bloomery process. The ability to modify the hardness of steel by heat treatment had been known since 1100 BC, and the rare material was valued for the manufacture of tools and weapons. Because the ancients could not produce temperatures high enough to melt iron fully, the production of steel in decent quantities did not occur until the introduction of blister steel during the Middle Ages. This method introduced carbon by heating wrought iron in charcoal for long periods of time, but the absorption of carbon in this manner is extremely slow thus the penetration was not very deep, so the alloy was not homogeneous. In 1740, Benjamin Huntsman began melting blister steel in a crucible to even out the carbon content, creating the first process for the mass production of tool steel. Huntsman's process was used for manufacturing tool steel until the early 1900s.[23]

The introduction of the blast furnace to Europe in the Middle Ages meant that people could produce pig iron in much higher volumes than wrought iron. Because pig iron could be melted, people began to develop processes to reduce carbon in liquid pig iron to create steel. Puddling had been used in China since the first century, and was introduced in Europe during the 1700s, where molten pig iron was stirred while exposed to the air, to remove the carbon by oxidation. In 1858, Henry Bessemer developed a process of steel-making by blowing hot air through liquid pig iron to reduce the carbon content. The Bessemer process led to the first large scale manufacture of steel.[23]

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon, but the term alloy steel usually only refers to steels that contain other elements— like vanadium, molybdenum, or cobalt—in amounts sufficient to alter the properties of the base steel. Since ancient times, when steel was used primarily for tools and weapons, the methods of producing and working the metal were often closely guarded secrets. Even long after the Age of Enlightenment, the steel industry was very competitive and manufacturers went through great lengths to keep their processes confidential, resisting any attempts to scientifically analyze the material for fear it would reveal their methods. For example, the people of Sheffield, a center of steel production in England, were known to routinely bar visitors and tourists from entering town to deter industrial espionage. Thus, almost no metallurgical information existed about steel until 1860. Because of this lack of understanding, steel was not generally considered an alloy until the decades between 1930 and 1970 (primarily due to the work of scientists like William Chandler Roberts-Austen, Adolf Martens, and Edgar Bain), so "alloy steel" became the popular term for ternary and quaternary steel-alloys.[24][25]

After Benjamin Huntsman developed his crucible steel in 1740, he began experimenting with the addition of elements like manganese (in the form of a high-manganese pig-iron called spiegeleisen), which helped remove impurities such as phosphorus and oxygen; a process adopted by Bessemer and still used in modern steels (albeit in concentrations low enough to still be considered carbon steel).[26] Afterward, many people began experimenting with various alloys of steel without much success. However, in 1882, Robert Hadfield, being a pioneer in steel metallurgy, took an interest and produced a steel alloy containing around 12% manganese. Called mangalloy, it exhibited extreme hardness and toughness, becoming the first commercially viable alloy-steel.[27] Afterward, he created silicon steel, launching the search for other possible alloys of steel.[28]

Robert Forester Mushet found that by adding tungsten to steel it could produce a very hard edge that would resist losing its hardness at high temperatures. "R. Mushet's special steel" (RMS) became the first high-speed steel.[29] Mushet's steel was quickly replaced by tungsten carbide steel, developed by Taylor and White in 1900, in which they doubled the tungsten content and added small amounts of chromium and vanadium, producing a superior steel for use in lathes and machining tools. In 1903, the Wright brothers used a chromium-nickel steel to make the crankshaft for their airplane engine, while in 1908 Henry Ford began using vanadium steels for parts like crankshafts and valves in his Model T Ford, due to their higher strength and resistance to high temperatures.[30] In 1912, the Krupp Ironworks in Germany developed a rust-resistant steel by adding 21% chromium and 7% nickel, producing the first stainless steel.[31]

Others

Due to their high reactivity, most metals were not discovered until the 19th century. A method for extracting aluminium from bauxite was proposed by Humphry Davy in 1807, using an electric arc. Although his attempts were unsuccessful, by 1855 the first sales of pure aluminium reached the market. However, as extractive metallurgy was still in its infancy, most aluminium extraction-processes produced unintended alloys contaminated with other elements found in the ore; the most abundant of which was copper. These aluminium-copper alloys (at the time termed "aluminum bronze") preceded pure aluminium, offering greater strength and hardness over the soft, pure metal, and to a slight degree were found to be heat treatable.[32] However, due to their softness and limited hardenability these alloys found little practical use, and were more of a novelty, until the Wright brothers used an aluminium alloy to construct the first airplane engine in 1903.[30] During the time between 1865 and 1910, processes for extracting many other metals were discovered, such as chromium, vanadium, tungsten, iridium, cobalt, and molybdenum, and various alloys were developed.[33]

Prior to 1910, research mainly consisted of private individuals tinkering in their own laboratories. However, as the aircraft and automotive industries began growing, research into alloys became an industrial effort in the years following 1910, as new magnesium alloys were developed for pistons and wheels in cars, and pot metal for levers and knobs, and aluminium alloys developed for airframes and aircraft skins were put into use.[30] The Doehler Die Casting Co. of Toledo, Ohio were known for the production of Brastil, a high tensile corrosion resistant bronze alloy.[34][35]

See also

References

- ^ Callister, W.D. "Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction" 2007, 7th edition, John Wiley and Sons, Inc. New York, Section 4.3 and Chapter 9.

- ^ Verhoeven, John D. (2007). Steel Metallurgy for the Non-metallurgist. ASM International. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-61503-056-9. Archived from the original on 2016-05-05.

- ^ Davis, Joseph R. (1993) ASM Specialty Handbook: Aluminum and Aluminum Alloys. ASM International. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-87170-496-2.

- ^ Metals Handbook: Properties and selection By ASM International – ASM International 1978 Page 407

- ^ Mills, Adelbert Phillo (1922) Materials of Construction: Their Manufacture and Properties, John Wiley & sons, inc, originally published by the University of Wisconsin, Madison

- ^ Hogan, C. (1969). "Density of States of an Insulating Ferromagnetic Alloy". Physical Review. 188 (2): 870–874. Bibcode:1969PhRv..188..870H. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.188.870.

- ^ Zhang, X.; Suhl, H. (1985). "Spin-wave-related period doublings and chaos under transverse pumping". Physical Review A. 32 (4): 2530–2533. Bibcode:1985PhRvA..32.2530Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.32.2530. PMID 9896377.

- ^ a b c Dossett, Jon L.; Boyer, Howard E. (2006) Practical heat treating. ASM International. pp. 1–14. ISBN 1-61503-110-3.

- ^ Metallurgy for the Non-Metallurgist by Harry Chandler – ASM International 1998 Page 1—3

- ^ Jacobs, M.H. Precipitation Hardnening Archived 2012-12-02 at the Wayback Machine. University of Birmingham. TALAT Lecture 1204. slideshare.net

- ^ Rickard, T.A. (1941). "The Use of Meteoric Iron". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 71 (1/2): 55–66. doi:10.2307/2844401. JSTOR 2844401.

- ^ Buchwald, pp. 13–22

- ^ Buchwald, pp. 35–37

- ^ Buchwald, pp. 39–41

- ^ a b Smith, Cyril (1960) History of metallography. MIT Press. pp. 2–4. ISBN 0-262-69120-5.

- ^ Emperor's Ghost Army Archived 2017-11-01 at the Wayback Machine. pbs.org. November 2014

- ^ Rapp, George (2009) Archaeomineralogy Archived 2016-04-28 at the Wayback Machine. Springer. p. 180. ISBN 3-540-78593-0

- ^ Miskimin, Harry A. (1977) The economy of later Renaissance Europe, 1460–1600 Archived 2016-05-05 at the Wayback Machine. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-521-29208-5.

- ^ Nicholson, Paul T. and Shaw, Ian (2000) Ancient Egyptian materials and technology Archived 2016-05-02 at the Wayback Machine. Cambridge University Press. pp. 164–167. ISBN 0-521-45257-0.

- ^ Kay, Melvyn (2008) Practical Hydraulics Archived 2016-06-03 at the Wayback Machine. Taylor and Francis. p. 45. ISBN 0-415-35115-4.

- ^ Hull, Charles (1992) Pewter. Shire Publications. pp. 3–4; ISBN 0-7478-0152-5

- ^ Brinkley, Frank (1904) Japan and China: Japan, its history, arts, and literature. Oxford University. p. 317

- ^ a b Roberts, George Adam; Krauss, George; Kennedy, Richard and Kennedy, Richard L. (1998) Tool steels Archived 2016-04-24 at the Wayback Machine. ASM International. pp. 2–3. ISBN 0-87170-599-0.

- ^ Sheffield Steel and America: A Century of Commercial and Technological Independence By Geoffrey Tweedale – Cambridge University Press 1987 Page 57—62

- ^ Experimental Techniques in Materials and Mechanics By C. Suryanarayana – CRC Press 2011 p. 202

- ^ Tool Steels, 5th Edition By George Adam Roberts, Richard Kennedy, G. Krauss – ASM International 1998 p. 4

- ^ Bramfitt, B.L. (2001). Metallographer's Guide: Practice and Procedures for Irons and Steels. ASM International. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-1-61503-146-7. Archived from the original on 2016-05-02.

- ^ Sheffield Steel and America: A Century of Commercial and Technological Independence By Geoffrey Tweedale – Cambridge University Press 1987 pp. 57—62

- ^ Sheffield Steel and America: A Century of Commercial and Technological Independence By Geoffrey Tweedale – Cambridge University Press 1987 pp. 66—68

- ^ a b c Metallurgy for the Non-Metallurgist by Harry Chandler – ASM International 1998 Page 3—5

- ^ Sheffield Steel and America: A Century of Commercial and Technological Independence By Geoffrey Tweedale – Cambridge University Press 1987 p. 75

- ^ Aluminium: Its History, Occurrence, Properties, Metallurgy and Applications by Joseph William Richards – Henry Cairy Baird & Co 1887 Page 25—42

- ^ Metallurgy: 1863–1963 by W.H. Dennis – Routledge 2017

- ^ "Doehler-Jarvis Company Collection, MSS-202". www.utoledo.edu. Retrieved 2024-08-16.

- ^ Woldman’s Engineering Alloys, 9th Edition 1936, American Society for Metals, ISBN 978-0-87170-691-1

Bibliography

- Buchwald, Vagn Fabritius (2005). Iron and steel in ancient times. Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. ISBN 978-87-7304-308-0.

External links

- Roberts-Austen, William Chandler; Neville, Francis Henry (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.